We should begin questioning the worth of “perfect” English.

“Standard English”

If a blindfolded stranger heard me speak, they would be able to tell that I am the product of a complete American education from early childhood, but that’s all. At home, I speak a merging of Chinese and English, both broken. Standard English in its articulate form comes naturally to me, but it makes communicating with my parents more difficult. I speak in simple, brief clauses and eliminate SAT words. My parents are very lettered people and would be considered scholarly in China, both being college educated in a time where it was rare. Yet in America, they are linguistically disadvantaged.

English speakers in the United States generally defer to Standard English without questioning how it comes so naturally. With each word, with each sentence, we perpetuate the myth of a Single American English with a bias toward Standard English (Use of language demonstrated via this whole essay). If we are looking for a new way to revolt, we should adopt a more nuanced way of thinking about language. At this critical juncture in time, language has an opportunity to metamorphose.

The newest president is overturning the historical standards for presidential vernacular. He frequently interrupts his own sentences with interjections, then interrupts those interjections with interjections, then repeats sentences incessantly as if intoning the chorus of a Top 40 song, all while consistently inhabiting the bullish cadence of a schoolyard bully.1 In 2017, what does America’s linguistic standards for their president elect reveal? English is accepted as perfect and standard as along as its speaker looks standard.

We should begin questioning the worth of PERFECT ENGLISH. If we love that Standard English is eloquent, clear, and allows for advanced discourse, we must concurrently recognize its villainous qualities, and its power to alienate those not inclined to it.

This year’s Literacy Review, a Gallatin publication, has been printed. I show it to my mother, and point out my name in the masthead in the myriad names listed under Editorial Board.

“It’s full of writing by adults who are learning English,” I say.

“This is very good quality paper,” my mother says in Chinese, flipping through the magazine. “It’s good that the school pays for this printing.”

I flip to a very short piece that is one of my favorites, called “Obama”.2 It is written by Livingstone Broomes. At the bottom corner of the page is his author portrait, taken by a Gallatin student photographer. In grayscale, it shows a wizened, serene black man. My mother begins reading the poem with the English she has accrued over the last twenty six years.

He is nice. “(She is nice.)”

He is a good dad. “(She is good dad.)”

He has a loving wife. “(She is a loving wife.)”

He is happy. “(She is happy.)”

He is handsome. “(She is handsome.)”

He looks like me. “(She look like me.)”

On the last line, my mother bursts out laughing. “(A bit full of himself, isn’t he?)”

Oh—that’s not totally what it’s supposed to mean. The precise humor has been lost in translation. For my mother, reading the poem in her second language has produced a literal interpretation of the last line. I begin explaining:

“Well, he’s just talking about, how Obama’s also black, like him, he’s not saying that he really thinks they look alike—”. My mother is nodding already. She understands the last line now, the way it is supposed to be understood. In the middle of my ramble, the realization had sprung up on me: I was performing some sort of variation on mansplaining.

Englishsplaining: explaining the significance of something believed to not have been concretely conveyed to my parent. Not an act of translation, exactly, it is an act of uprooting the first understanding and imposing my own understanding. Englishsplaining comes out of good intentions; I just want my mother to understand things the specific way I understand things. It is ultimately patronizing. Englishsplaining conjures up the history of Western imperialism attempting to Christianize and assimilate the other. In trying to make my mother understand English, I play the didactic patriarch who reminds her, this land is their land.

Doubly my fault, I have not sustained any sort of routine in practicing and perfecting my Mandarin Chinese; instead, I spend that time reading American writers. The oppressor giving herself leeway. And admitting it allows me to realize, the beauty of perfect English that I revel in when I read a classic novel, the integrity of that sort of perfect English is a tenuous one, in the space of an immigrant family like mine. Standard English retains its imperialist legacy, and in its worst, most quietly abusive form, uses people like me to persist.

Our education system, our curricula, reflect the monolinguistic thinking that dominates U.S. classrooms. Ever since the reform movement for regulated schools in the late nineteenth century, our education system has uniformly espoused Americanization, comprised of imposing expectations of English fluency on Eastern European immigrant children, Native American children, and since then other foreign groups, notably, Latino immigrants and Asian immigrants. But education reform for Americanization did not ask permission from these immigrants, nor take into account their specific needs for learning. As a result, there has been pushback from those communities. Two court cases of the 1970s tell a narrative of Chinese American children’s fraught relationship with common school education under the San Francisco Unified School District.

In Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson (1971), a case brought by concerned Chinese parents, the court upheld desegregation of Chinese students in San Francisco. Chinese students, previously in schools especially fitted to the Chinese community, were reassigned to public schools. Justice William O. Douglas wrote the decision for the case, emphasizing that heterogeneity in education was fuel for social disorder: “In the end, that response may well be decisive in determining whether San Francisco is to be divided into hostile racial camps, breeding greater violence in the streets, or is to become a more unified city demonstrating its historic capacity for diversity without disunity.”3

The instinct to assimilate the Chinese students into the Standard English, presumably in schools with predominantly white administrations, evokes a white school swallowing and vanquishing the Chinese experiences of the Chinese youth. In the decision, justice William O. Douglas fixates on desegregation as a unifying movement, yet he never clarifies the cultural makeup of this unity that he envisions. It is specifically a district board and a court that is out of touch with the Chinese community that led this case, Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson, to have an offspring case three years later in Lau v. Nichols (1974).

Lau v. Nichols was a class action brought by 1,800 of the 2,800 Chinese students who had been transitioned into the desegregated schools.4 Those 1,800 had not received adequate supplemental schooling to accommodate their linguistic and cultural needs in the space of Standard English classrooms. Those young people lived their entire lives in a particular space, San Francisco’s Chinatown, as well as its schools. In terms of experience, the classroom with Chinese peers and instructors is a space worlds apart from the white-ordained desegregated classroom.

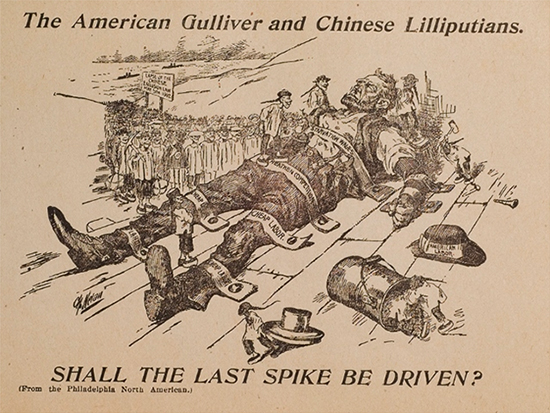

Historically, the Chinese community’s isolation in their own spaces was caused by the government’s and Western people’s othering of them (Yellow Peril). In the 1902 drawing called “The American Gulliver and Chinese Lilliputians”, the Philadelphia branch of the American Federation of Labor depict Chinese railroad workers as a horde of leering lilliputians nailing down with spikes and hammers a giant Abraham Lincoln-esque man, who represents American labor. The steel pieces that attach Abraham Lincoln to the ground say the words “cheap labor” and “heathen competition”. Images like this one that caricaturized and dehumanized Chinese workers, left out the realities of Chinese experience in railroad construction. Central Pacific Railroad provided no housing for Chinese workers so they lived in makeshift tent towns on mountains, in any climate including winter.

In that same year as the decision of Lau v. Nichols, acting professor of law at University of California Berkeley, Stephen D. Sugarman, gave a reaction to the case in the California Law Review. In the case commentary titled “Equal Protection for Non-English Speaking School Children,” he pointed out that it was government policies and legislations that had caused the Chinese community’s isolation and living conditions in America: “In San Francisco, most Chinese immigrants first settled in Chinatown, a crowded, impoverished, and Chinese-speaking ghetto, and large numbers of Chinese-Americans remain trapped there.”5 Still, within the world of Chinatown, those immigrants’ language, social experiences, and sense of community, was valid. When the government took Chinese students out of Chinese schools and placed them jarringly in desegregated classrooms where English was the only accepted language, the government disadvantaged the students’ basic survival by rendering their pre-existing experiences nonexistent and unuseful. Sugarman noted that a school system not specially designed for these Chinese students could not be particularly helpful to them.

In my own experience, I entered the American public school system at the age of four, after staying in China for most of my childhood. Upon entering kindergarten, I was also put in a English as Second Language class. Though the students in ESL were ethnically varied, there was one teacher for all of us, and her only second language was Spanish. My linguistic fluency in Mandarin Chinese, and social experiences as a Chinese person, were unacknowledged and at the same time treated as an obstacle; in that classroom, the fixation was on my lack of English ability, my unplace in the American community. It was a stressful experience for a five year old to be corrected in every word.

A decade later, I realize that the Americanization of someone of “other” identity necessarily includes the oppression of their other identity. Only in college, in the depths of my formal education, have I begun to use my Americanization and Western education to confront the oppressive systems and reclaim my identity and embrace nonStandard English in my writing. I imagine many of those students in the class-action case of Lau v. Nichols never were afforded the chance to reclaim their Americanization in the same way.

American professors of education have identified the process of Americanization as reliant on its English language as foundation for indoctrination. Lavada Brandon, Denise Baszile, and Theodora Berry, in their paper “Linguistic Moments: Landguage, Teaching, and Teacher Education in the U.S.,” remark of the placement of bilingual children in monolingual schools: “Standard English became the vehicle used to transmit and maintain Anglo-American culture and language. Immigrant children soon learned that if they wanted to succeed in American society, they needed to acquire the language of dominant discourse; they needed to know Standard English.”6

And so I have absorbed arguments and reckonings of scholars and professional experts, done all the readings, read inside my head in Anglo-American vernacular, embodied all this knowledge about the human race through a Western lens. I know a little about a lot of cultures, how they have been oppressed and how they have been liberated, and how forms of oppression and liberation always evolve into sneakier creatures in order to survive.

It is through reading the texts of courses like Social Foundations, a series of required courses that constitute the “Core Program” at NYU’s Liberal Studies Program, which employ the voice of Standard English and are published to academic standards of a system owned largely by rich white patrons, that the presence of oppression in every crack and groove of existence is gradually illuminated. At its highest levels, American education is streaked with paradox. The university, as with many institutional spaces, is a symbiotic coexistence of liberation and oppression, education and indoctrination.

Course texts have been majorly responsible for guiding me in making sense of contradictions in my own life and identity. Unlike high school, where the curriculum focused on symbolism or linear themes, liberal arts classrooms in college attempt to create meta-awareness and illuminate interconnections throughout domestic and global narratives. It’s through a college education that I’ve arrived at this understanding: This linguistic gain over the course of fifteen years has quietly created a loss. In worshipping good English as personal capital, I have almost discontinued my linguistic heritage from outside the United States. In 2017, I hate my perfect English as much as I love it. I want to question this notion of perfect English and find a way to challenge it, but not too soon. First step, I have to address my general relationship with language. And so I have created some personal guidelines:

- Do not confuse linguistic ability with intelligence, nor operate from an ethnocentric point of view when confronted with an unfamiliar language, dialect, or accent. A feeling of unfamiliarity on the part of the beholder signifies the beholder’s gap in knowledge of other cultures rather than the other person’s cultural shortcomings.

- Identify my capacity to oppress when it arises. Eradicate the impulse to correct nonStandard English that confronts me. Instead, let it fill the space and let it be meaningful. Listen and allow myself to not understand, which I can learn from as much as understanding.

- bell hooks said in her 1994 critical text about classroom education, it is “difficult not to hear in standard English always the sound of slaughter and conquest.”7 So I shall allow myself, regularly, to hear in perfect English the sound of slaughter and conquest, as a practice in reckoning.

Those who believe a deviation from Standard English would be detrimental to communication must realize that an actual deviation from Standard English, or de-standardizing English, eradicating eloquent use of English language, is altogether impossible. Standard English is the natural way of educated people or longtime American citizens. However, many lettered people or people who speak English fluently should simply reckon with the historical implications of their conception of “perfect English.”

- “Presidential Candidate Donald Trump Campaign Event in South Carolina.” C-Span. July 21, 2015. Video. https://www.c-span.org/video/?327258-1/donald-trump-remarks-sun-city-south-carolina

- Broomes, Livingstone. The Literacy Review, Vol. 15, Spring 2017, New York: Gallatin School of Individualized Study. p. 72

- Justice William O. Douglas. Guey Heung Lee v. Johnson 404 U.S. 1215 (1971) U.S. Supreme Court. Decided August 25, 1971.

- Justice William O. Douglas. Lau v. Nichols 414 U.S. 563 (1974) U.S. Supreme Court. Decided January 21, 1974

- Stephen D. Sugarman and Ellen G. Widess. “Case Commentaries: Equal Protection for Non-English-Speaking School Children: Lau v. Nichols.” California Law Review. Vol 62. January 1974.

- LaVada Brandon, Baszile, Denise Marie Taliaferro; Berry, Theodore Regina. “Linguistic Moments: Language, Teaching, and Teacher Education in the U.S.” The Journal of Educational Foundations; Ann Arbor, Winter 2009. p.47-66.

- bell hooks. “Teaching New Worlds/New Words.” Teaching to Transgress. Routledge September 14, 1994. Pp. 167-175.