13. Wheat-Meal Bread-Graham Bread. “In every cook-book I have examined, and in allRead More

Graham’s Crackers Crumble

13. Wheat-Meal Bread-Graham Bread.

“In every cook-book I have examined, and in all the medico-dietetical works I have consulted, I find saleratus or pearlash, and salt always in the recipe for making what those books call brown, dyspepsia, or Graham bread.Those two drugs ought always to be left out. Molasses or brown sugar is also a fixture in the ordinary recipe books, and as a small quantity—a tablespoonful to a common loaf—is not harmful, the saccharine element may be left to taste. Make the sponge of unbolted wheat-meal in the ordinary way, with either hop or potato yeast, but mix it rather thin. Be sure and mold the loaves as soon as it becomes light, as the unbolted flour runs into the acetous fermentation much more rapidlythanthe bolted or superfine flour, and bake an hour an a quarteror an hour and a half, according to the size of the loaf.”–Graham Bread Recipe from The New Hydropathic Cook-Book1

In one of Sylvester Graham’s more influential lectures, his 1829 A Lecture to Young Men on Chastity: Intended Also for the Serious Consideration of Parents and Guardians, his Preface seems characteristically self-important. Although the historical details of Graham delivering this lecture are scarce, the lecture’s purposeful and self-important attributes ooze from its written documentation. According to Graham, it took courage to discuss a topic of “delicacy and difficulty”—namely, that of sensual appetites—and it seems Graham thought that only he had the true nerves to demand extreme dietary and sexual reformation. This self-importance is particularly apparent in this passage from the lecture’s first edition Preface in which Graham writes:

[I]t did not, in any degree, enter into my plan, to treat on this delicate subject: but the continual entreaties, and importunities, and heart-touching—and I might truly say heart-rending—appeals which I received from young men, constrained me to dare to do that which I was fully convinced ought to be done; and the result has entirely justified my decision and conduct … Hundreds who have listened to the following Lecture, have thereby been saved from the most calamitous evils: and great numbers … have urged me to publish it. On this point, I have long hesitated; —not, however, because I doubted the intrinsic propriety of publishing it, but because I doubted whether the world had sufficient virtue to receive it, without attempting to crucify me for the benefaction. 2

Graham did not only explain the need for societal reform but he also offered solutions. He identified that man has two grand functions of his system—nutrition (digestion) and reproduction—and because there were connected, dietary reformation could be a beneficial step in the correct direction for avoiding the negative sensibilities “of the genital organs [and] their influence on the functions of organic life.”3 Graham bread, and its derivative the Graham cracker, were his dietary reformation’s keystone.

Graham bread, first made in 1829 from wheat that was unbolted and “unpalatable,” was to be used as a substitute for the “stimulating and heating substances, high seasoned-food, [and] rich dishes” that were making life in Antebellum America impure.4, 5 Graham’s dietary reform was in line with the Popular Health Movement of the 1830s. The Graham cracker and the Graham diet, however, rather than ever being successfully applied, highlighted how theories can fail to bridge the gap between intangible thought and implementation.

Nonetheless, the timing seemed perfect for Graham’s theoretical reforms. The Popular Health Movement of the 1830s was a product of the broader Jacksonian democracy that worked toward empowering the “Common Man” and his political influence. John C. Gunn, author of the 1830’s Gunn’s Domestic Medicine or Poor Man’s Friend, In the Hours of Affliction, Pain and Sickness, a medical tome with the purpose to “[point] out, in plain language, free from doctors’ terms” medical remedies helpful to families, characterized the Popular Health Movement like this: “political equality becomes synonymous with ‘equality in knowledge,’ and tyranny is fought by the ‘equalization of useful intelligence’ among American citizens … Health becomes crucial in these Jacksonian equations because, without health, intelligence, the building block of republican government, becomes impaired and feeble. Citizens must be healthy in order to be politically free.”6, 7 Combined with the Evangelical Protestants’ missionary style to reform, the Popular Heath Movement aimed at purifying the American life and the American diet specifically. As Daniel Sack writes in White Bread Protestants, “For many of these evangelical reformers, the American diet was as scandalous as slavery and drunkenness.”8 The Graham cracker and its creator addressed these concerns with sobering lifestyle modifications.

Sylvester Graham and his theories, which seemed ingrained in Graham’s life story, fit nicely at the forefront of the time’s dietary crusade. Born in Suffield Connecticut in 1794 when his minister father was 72, Graham was a sickly child whose interest in dietary health may have been motivated by this experience.9 Graham was ordained as a Presbyterianin 1829, andafter becoming the General Agent for the Pennsylvania Temperance Society in 1830, he delivered a series of lectures up and down the East Coast of the United States, which were often about vegetarianism, life without luxury, and the dangers of masturbation. These lectures made him a “celebrity and a force.”[10. Sack, D. (2000).White Bread Protestants. (p. 188). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.], 10 The biographer James Parton, a contemporary of Graham, noted the level of Graham’s celebrity when he wrote that he “arose and lectured and made a noise in the world, and obtained followers … Graham was a remarkable man … one of the two or three men to whom this nation might, with some propriety, erect a monument.”11 Graham’s force was perhaps unexpected, as Gerald Carson, in his book Cornflakes Crusades, explains: “Despite his pinched life as a quasi-orphan, his father dead, his mother gone mad, despite a patchwork education, incipient tuberculosis, a late start in life, the burden of a wife who sometimes took a little wine or gin for her stomach’s sake, and a brood of children, Graham tackled life confidently with the forces at his disposal.”12

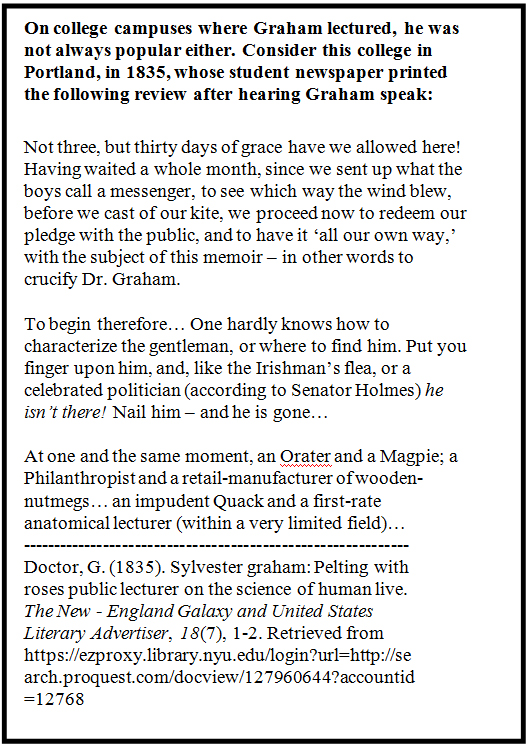

Perhaps even more bewildering was Graham’s elusiveness. As John P. Coleman says in his paper, “Casting Bread On Troubled Waters: Grahamism and the West,” published by Siena College, “The public was quick to label as ‘Grahamism’ the system outlined in A Lecture to Young Men. Its author, however, had only minimal contact withthe societies, boarding houses, and the journal established to promote his ideas.”13 Graham did not even initiate the journal that bore his name, the Graham Journal of Health and Longevity, which was instead started by David Cambell in 1837 to promote Graham’s ideas throughout American society. Graham seemed to have created and announced his system and then left it to others to implement. Perhaps this helps explain why Graham’s philosophy had such trouble realizing itself in practice. Not having the leader around to implement his theory proved difficult, especially when the theory was one that, in suggesting a severe lifestyle change, sometimes caused dramatic backlash.

Implementing theory is not easy. People are bound to disagree with suggested reform. And not everyone appreciated Graham’s suggestions; some even had visceral reactions. Consider this section of an article published on March 10, 1908, in the San Francisco Call:

“Graham met with great opposition, however, from butchers and bakers. They became so angry one day in Boston in 1847 over his series of lectures, in which he advocated people giving up meat eating, that a mob of butchers and bakers surrounded the hall in which he was lecturing and threatened violence. Some of the followers of Graham, strict vegetarians, thought out a scheme to disperse the crowd even if the Boston police couldn’t. They procured some slaked lime and shoveled it out the windows of the hall where Graham was lecturing onto the heads of the mob below. Slaked lime was altogether too much for even a Boston mob to face and they presently left the neighborhood and let the Grahamites have their way.14

By 1847 Graham clearly had to be careful as he pushed his reforms on the general American public. They stirred up volatile reactions for those who were not committed Grahamites. While Graham himself could be an elusive figure—he was known to show up, give a lecture that agitated locals, and then leave—his theory required a home base that was less unpredictable. In 1840, before his ideas spurred such volatile reactions in Boston, his theory gained traction in what should have been the perfect time and place for its implementation. It was during this Popular Health Movement, at a place, Oberlin College, that was desperately seeking purity in a remote and controllable environment.

Religion and living the pure life were paramount in Oberlin’s earliest days, and in their pursuit of purity dietary reform was important. When Oberlinwas founded, in 1832 and 1833, the Oberlin Covenant was drafted and contained a series of articles of agreement. This was its spirit: “Lamenting the degeneracy of the Church and the deplorable condition of our perishing world, and ardently desirous of bringing both under the entire influence of the blessed gospel of peace…”15

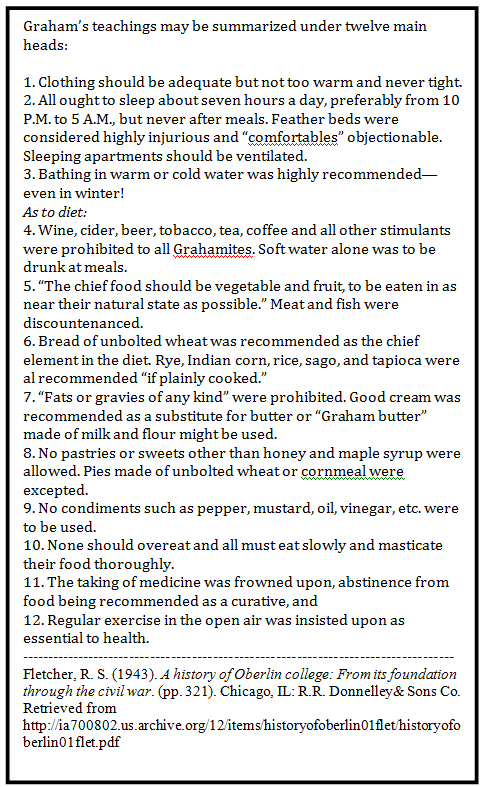

The men and women of Oberlin were therefore expected to make righteous life choices, and an important part of this charge included dietary restraint.The fifth article of the Oberlin Covenant stated, “That we may have time and health for the Lord’s service, we will eat only plain and wholesome food, renouncing all bad habits, and especially the smoking and chewing of tobacco, unless it is necessary as a medicine, and deny ourselves all strong and unnecessary drinks, even tea and coffee, as far as practicable, and everything expensive, that is simply calculated to gratify the palate.”16 Maintaining a righteous, bland diet was required by the school’s creed and so the Graham cracker should havebeen welcomed into Oberlin society.

Not only was Oberlin ideologically ready to receive Graham’s theories, but its remote setting offered an environmentthat ought to have been insulated from the type of Bostonian mob scene that Graham later encountered. James Harris Fairchild, a freshman the year Oberlin opened and the institution’s third president, explained in his 1860 address to alumni, Oberlin its Origin, Progress and Results, just how remote the college was: “There are probably ladies among us to-day who were obliged, in coming to the school from their Eastern homes, to walk the last two or three miles through mud and water to the ankle.”17 Oberlin’s location was not just remote, but it also seemed preordained to be a place of spiritual purity. Extreme faith and purpose convinced the founders of the school that this rocky land, left untouched by previous settlers, was to be the site of their pure school. In his same 1860 alumni address Fairchild explained, “There is no question that Northern Ohio presented many more desirable localities; but there was probably no other where Oberlin could have been built. Places could have been found in 1620—excuse the comparison—presenting a more genial climate and soil than Plymouth on the bleak New England coast, but who would now dare to remodel history and direct the Mayflower to the mouthof the Hudson or of the Savannah? ‘The foolishness of God is wiser than men.’”18 Safe from urban mobs and defending its secluded location as preordained, Oberlin offered the perfect place to implement Graham’s severe and pure dietary theories.If it couldn’t be done here, how could Grahmism be implemented anywhere?

Graham himself never appeared at Oberlin, and perhaps this characteristic aloofness helps account for why his theory had trouble making the jump into viable practicality. Nonetheless, despite the movement’s leader’s absence the Graham lifestyle was established at Oberlin. The religious leaders of the school, including the Presbyterian minister co-founders John Jay Shipherd and Philo P. Stewart, professor of theology Charles Grandison Finney, and the U.S. Congregational clergyman and Oberlin’s first president Asa Mahan, were all dedicated Grahamites. In fact, just as the Popular Health Movement and the Oberlin Covenant acknowledged, they too saw dietary reform as important steps towards pursuing purity. As Asa Mahan explained in a 1839 address before the American Physiological Society: “The individual who voluntarily destroys his life, or injures his health, voluntarily annihilates or diminishes his power of doing good; in other words of accomplishing the purposes of his moral being.”19 Health was of the utmost importance, and beginning with the dietary restrictions of the Oberlin Covenant, the school’s dietary rules grew stricter year by year in pursuit of implementing a Grahamite diet.

By 1834 the school was living quite closely under Graham’s teachings. Diet, at first, was regulated in the dormitory by a Mr. and Mrs. Stewart, likely the same Philo P. Stewart who co-founded the school, but in 1836 when the Stewarts departed, a joint student-faculty started regulating the diet and there was worry that the regulation was not aligned closely enough with Graham’s theory.20 So in the pursuit of purity, Oberlin invited David Cambell, the editor of the Graham Journal of Health and Longevity and secretary of the American Physiological Society, to really put Graham’s theory into practice.

Turning theory into practice meant creating a sort of a Grahamite cult at Oberlin, which the school culture seemed ready to accept. The leader of this cult, David Cambell, whose wife also came with him to Oberlin, made quite the entrance on the scene. Robert Samuel Fletcher explains in his A History of Oberlin College: “The two Cambells caused no little excitement when they arrived in Oberlin in May of 1840, bringing a cask of rice, a cask of tapioca, a box of sago and a copy of Nature’s Own Book, containing recipes for Graham bread … and other reformed dishes!”21 The menu at the boarding house changed dramatically and Graham bread was a staple and celebrated part of the cult: in July of 1839 Sarah P. Ingersoll, a student at Oberlin wrote home saying, “‘I want to have the privilege of baking as much as once for you, and I want you to provide a quantity [of] first rate Graham flour, that you may have at least one oven full of coarse food if not more. I know father will like it, and I think mother and the children will.”22 Oberlin, it seemed, was embracing Graham’s theory. But given Cambell’s application of Grahamism, the school was unprepared with a successful way to respond to the nonconformists.

Those who did not abide by the rules of the cult were either inconvenienced for their nonparticipation or exiled from the community all together. For example, those students who, as Robert Fletcher explains, “required” meat, which Cambell felt he could not rightfully serve, had to wait eleven months while the Oberlin “Prudential Committee” met and conferred with faculty about the issue. Only after this long delay was meat finally brought to the halls, and it was delivered in such a way that the Cambells did not need to manage it.23 Other nonconformists were dismissed from the cult, as when professor John P. Cowles, “an unmarried professor who took his meals at the boarding house,” brought a peppershaker to the table and the trustees forced him to remove it. Cowles was dismissed from his teaching post soon after.24

Through Cambell, Grahamite theory was put into practice at Oberlin, and although it was able to manage some disturbances, the cult soon met heavy opposition. This backlash, if you will, was likely brought on because, especially at the beginning of the “Cambell cult,” many students lived on a diet of bread and water or bread and salt alone. An entire college was eating Graham crackers and water day in and day out. As one might expect, discomfort ensued; one student wrote home to his father that he was “absolutely hungry a good part of the time.”25 Besides those discomforted or suffering hunger pains, there were those who spoke out about the ludicrousness of the “Cambell cult.” Professor Cowles, for example,who’d been dismissed for bringing the peppershaker to the meal table, charged that “the physiological reform at Oberlin went ‘beyant all the beyants entirely.”26 To the Cleveland Observer, Cowles blamed the Graham system with having caused a female student’s death: “But you [the Oberlin trustees] … have simplified simplicity, and reformed reformation, till not only the health and lives of many are in danger; but some, I fear, have already been physiologically reformed into eternity.”27 In practice Graham’s theory was just too coarse, even for those desperately seeking purity at Oberlin.

Implementation of Graham’s system continued to flail as loud and creative voices continued to rail against Grahamism. In the midst of these “attacks,” Delazon Smith, “Oberlin’s most unrelenting critic,” raised his voice veraciously against the dietary torture of Cambell, against Graham’s theory, and against the terrible tasting Graham bread.28 I defer to Robert Samuel Fletcher’s account of Mr. Smith’s criticisms:

“[Delazon Smith] declared that the food at the boarding house was “State Prison Fare!” He was more was more explicit: ‘As for their water gruel, milk and water porrages[sic], crust coffee &c., they are really too filthy and contemptible to merit a comment. They are usually known among the students by their appropriate names, such as Swill, starch slosh, dishwater,&c., &c. One of the above with an apology for bread, constitute the essentials of each meal.’ He held that ‘if students could not purchase other articles of food at the stores, tavern, &c., it would be utterly impossible for any of them to sustain their healths, if not their lives, or be obliged to leave these heights of zion.’ The people of the neighboring towns, he said, had become so well acquainted with the effects of Oberlin diet that they could identify a young man from Oberlin by his ‘leak, lean, lantern jawed visage!’ Smith quotes an Oberlin poet as expressing the situation perfectly:

‘Sirs, Finney and Graham first—’twere shame to think

That you, starvation’s monarchs, can be beaten;

Who’ve proved that drink was never meant to drink,

Nor food itself intended to be eaten—

That Heaven provided for our use, instead,

The sand and saw-dust which compose our bread.’”29

With people hungry and others sending letters to reporters, with students sneaking out to supplement their diets at the local taverns and restaurants, with creative faultfinders using their art to express their disdain, and with Dalezon Smith against it, Graham’s theory was failing. Oberlin was the perfect place for Graham’s teaching to be put into practice. And yet, in March 1841, not long after Cambell’s arrival a mass meeting was called, during which it was argued that “the health of many of those who board there [at the Hall] is seriously injured … not only in consequence of a sudden change of diet, but also by the use of a diet which is inadequate to the demands of the human system as at present developed.”30 Cambell, forced by “public opinion and private pressure,” resigned his stewardship overOberlin’s food that April, 11 months after he first arrived at the school.31 At the college, as was happening all across the country, Graham’s following was rapidly declining.Even in the most ideal setting, theory had failed in its implementation.

- Trall, R. T. (1855). The New Hydropathic Cook-book. (p. 162). New York, NY: Fowlers and Wells, Publishers. Retrieved from http://www.americancenturies.mass.edu/collection/itempage.jsp?itemid=11095&level=advanced&transcription=0&img=1

- Graham, S. (1848). A lecture to young men on chastity: Intended also for the serious consideration of parents and guardians(p. 12 – 13). Boston, MA: Light & Stearns, Crocker & Brewster. Retrieved from http://ia700501.us.archive.org/1/items/lecturetoyoungme00grah/lecturetoyoungme00grah.pdf

- Graham, S (p. 47)

- The story of graham flour. (1907, August 12). Los Angeles Herald. Retrieved from http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=LAH19070812.2.50

- Graham, S (p. 47).

- Gunn, J. C. (1860). Gunn’s domestic medicine or poor man’s friend, in the hours of affliction, pain and sickness. (p. title page). New York, NY: C.M. Saxton, Barker & Co., 25 Park Row. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=U90_-5e4d1wC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0

- Burbick, J. (1994). Healing the republic: The language of health and the culture of nationalism in nineteenth century America. (p. 37). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Popular_Health_Movement

- Sack, D. (2000).White Bread Protestants. (p. 188). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Sack, D. (2000).White Bread Protestants. (p. 188). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

- Carson, G. (1957). Cornflakes crusades. (p. 43). New York, NY: Rinehart & Company, INC.

- Carson, G. (p. 44).

- Carson, G. (p. 45).

- Coleman, J. P. (1986). Casting bread on troubled waters: Grahamism and the west. The Journal of American Culture, 9(2), 2.doi: 10.1111/j.1542-734X.1986.0902_1.x. Retrieved from https://www.siena.edu/uploadedfiles/home/neh/readings/CastingBread.pdf

- “How graham bread came to be made: Invention of Sylvester Graham, first real vegetarian of our times: He was mobbed by the bakers and butchers of Boston in 1847” (1908, Month 10). The San Francisco Call. Retrieved from http://cdnc.ucr.edu/cgi-bin/cdnc?a=d&d=SFC19080310.2.78

- Fairchild, J. H. (1860). Oberlin its origin, progress and results: An address, prepared for the alumni of oberlin college. (p. 4)Oberlin,OH: Shankland and Harmon. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=C3wMAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=

- Fairchild, J. H. (1860). Oberlin its origin, progress and results: An address, prepared for the alumni of oberlin college. (p. 4)Oberlin,OH: Shankland and Harmon. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=C3wMAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=

- Fairchild, J. H. (p. 9)

- Fairchild, J. H. (p. 6)

- Mahan, A. (1839). Intimate relation between moral, mental and physical law.The Graham Journal of Health and Longevity, 3(10), 154. Retrieved from http://books.google.com/books?id=HNMsAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA154&lpg=PA154&dq=#v=onepage&q&f=false being&source=bl&ots=nVx18PGqMe&sig=Hg6a172LIHSY5_lG1Jthw0gXaqE&hl=en&sa=X&ei=KV9cUtmRB4_j4AOF3YDgCw&ved=0CC4Q6AEwAA

- Fletcher, R. S. (1943). A history of Oberlin college: From its foundation through the civil war. (pp. 321 – 322). Chicago, IL: R.R. Donnelley& Sons Co. Retrieved from http://ia700802.us.archive.org/12/items/historyofoberlin01flet/historyofoberlin01flet.pdf

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 324).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 325).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 325).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 326).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 327).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 328).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 328).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 328).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 328 – 329).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 329 – 330).

- Fletcher, R. S. (p. 330).