“There were sensual photoshoots, repetitive interviews, and many asymmetrical haircuts.” On femininity, authenticity, and failed categories of rock music.

Grimes vs. Del Rey

Grimes took the blogosphere by storm. She was praised, gushed over; blog Gorilla vs. Bear was perhaps the first to hype the new album, with GvB creator Chris Cantalini playing the lead single “Oblivion” nearly every week on his blog radio show on SiriusXM for months prior to the album dropping. There were sensual photoshoots, repetitive interviews, and many asymmetrical haircuts. By the time her latest, Visions, was released, Canadian producer/singer, whose given name is Claire Boucher, had moved into the forefront of the indie world: for Visions, she moved to 4AD, one of the most successful indie labels. She had created and produced this music, but the public seemed most taken with her strange beauty, her dyed hair, oversized military clothing, her thin frame.

Almost every interview asks if Boucher, a pop star and a producer, draws inspiration from any female pop stars—female pop stars, as opposed to just pop stars. When asked if she feels sexualized, she promptly responds that she looks “like a baby” and that any sexiness attributed to her is only projected—it can’t be related to her body. She’s been known to cry on stage out of frustration to get the sound that she truly wants: a crisp, hypnotic, self-perpetuating aesthetic. Sometimes, this tendency cuts her live sets short. Her vulnerability (and, frankly, stubbornness) on stage is often ignored by the press, who have portrayed her as a hyper, radioactive nymph. With her synthy, catchy loops and her signature high-pitched voice, Boucher almost mimics the sounds of retro video games. Folklore has surrounded her, and heavyweight blogs have followed her every move: Pitchfork reported on a Huck Finn-esque ride down a river with her then-boyfriend and some chickens on a boat made of trash; GvB, always in her court, had her curate the site for a day; music sites from Stereogum to Paste magazine to smaller blogs posted on the premiere of her music video for her single “Oblivion.”

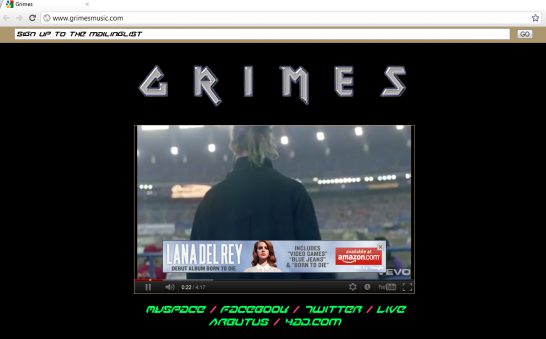

This narrative sounds familiar; and there are two sides to this coin. The very same blog that initially endorsed Grimes, GvB, featured the video of another then-unknown young female pop singer with a close attention to her image and specific sound. But in this case, they sparked what would be a now-infamous case of cyber bullying. GvB’s Cantalini posted the video for Lana Del Ray’s haunting “Video Games,” which featured found, vintage footage of Hollywood, landscapes, and suburbia as well as images of Del Rey herself, a waif with puffed lips, flowing hair, long eyelashes, and French-tipped nails. The sultry sound did not match her physical image, and Del Rey became the punch line to every joke in the indie blogosphere. There were questions of her authenticity, of her name change, of her espousing a false image of herself, but slowly, the conversation moved to surround her body. Even in T, the New York Times’ style magazine, in a cover feature on Del Rey, journalist Jacob Brown admitted he “had to ask” whether or not her lips were real or injections.

In an interview with Dummy magazine, promoting Grimes’ debut LP in 2010, Boucher states, “Not knowing how to play music is my greatest asset. . . . I try to imitate things, and then I fail horribly, and then it’s just . . . something different.” The lure to Grimes was the same what drew listeners to Del Ray, and yet Boucher’s authenticity was not in question. And so, the battle over Del Rey’s authenticity wasn’t really about authenticity at all.

Though it is in the positive, the Grimes phenomenon is conjured by the same fascination that Del Rey sparked. Recently, when watching an online music video for “Oblivion,” which, like “Video Games,” focuses its lens on the woman behind the music, an ad popped up, advertising Del Rey’s new album, Born to Die. Even Google’s analytics know that the audiences for these two singers are inherently similar. The indie blog world is still young—the first mp3 blog as we know them was started by Matt Perpetua in 2001—and the dynamics of the different “breeds” of artists are still in flux: women with a poppy sound hold a different kind of space from the rockist five-piece group (see: Cloud Nothings) or the veterans of the genre (see: Leonard Cohen). Stand-alone female artists in this context are rare creatures. Perhaps it is not a conscious decision for blogs like Pitchfork, GvB, and the like to become infatuated by these female artists, and yet infatuation seems to be their only mode of engagement. Grimes even notes in a Pitchfork interview that most of the time women need to be attractive to make it in the industry. This doesn’t speak to their talent or authenticity at all, but rather, it is telling of the indie blog audience.

What’s more, it seems that female acts like Grimes and Del Rey must engage, or even embrace these categorizations within the confines of the Internet in order to be visible to and recognized by powerhouses such as Pitchfork. Often, what this means is that women new to the field have to make a sort of meme of themselves. Del Rey embodied the voluptuous, retro, Elvis-influenced goddess—an image that does not quite suit the blog audience’s taste, as it seems dishonest; a persona, not a person to be all the time. But Del Rey held her ground and stuck to her image, which caused controversy and attacks on her legitimacy and talent. Grimes took on a better-accepted meme for indie readers: the pretty girl with the weird haircut who’s into David Lynch films. Without a character to embody, it is difficult for their voices to be heard. This is not to say that parts of these characters aren’t drawn from the actual woman, but these Internet-driven aspects are exaggerated and capitalized upon. With each character, this strange, embellished, feminine character, comes an intense fascination. They capture a specific place in the Internet, the space in which these blogs exist exclusively.

The blog world prides itself in existing outside of the mainstream media, but it is still susceptible to and perpetuating the same tropes that the mainstream media is: female fascination and an emphasis on image. These walls still exist, regardless of the platform.