“Dilma Rousseff’s public persona as head of state threatened traditional values. Thus, her impeachment was a twofold attack from the Right.”

Hysterical Dilma?

Female Identity in Revolutionary Politics, the Pink Tide’s Right Turn, and the Polarizing Image

of Dilma Rousseff

Dilma Rousseff’s impeachment, beginning in 2015, was a carefully orchestrated attack to undermine popularity and success of the Worker’s Party (PT) and to reorient Brazil within the neoliberal world order. Resentment within the upper-middle class over stagnant social standing as the poor continued to experience (albeit small) material gains, an antagonistic internationalist Brazilian bourgeoisie, the growing economic crisis, and Rousseff’s wavering commitment to traditional leftist policies opened a space for the Right to attack.

Rousseff’s identity as a woman, which was pivotal to her electability in 2010, subsequently led to misogynist coverage that contributed to her indictment as an incapable, and even hysterical, leader unable to overcome corruption within her administration. This image was an extension of the conservative values of the Right. Rousseff’s downfall was used as another channel to undermine participatory democracy in Brazil and the Left’s preference for the poor, a pattern which can be observed not only in the Brazilian case, but in the recent challenge to and rejection of Latin American pink-tide governments across the region. Critical analysis of the fixation upon Rousseff’s female identity is lacking, particularly in the United States, and this points to the acceptance of the space left, even in postrevolutionary society, for antiquated notions of gender to fester and the limited roles for a female revolutionary.

Coverage of the impeachment attempted to turn Rousseff into a culpable budget manipulator and incompetent ruler, one who maneuvered her way into the presidency, aided by the popularity of her predecessor, Lula. Once it is accepted that the PT and Rousseff were targeted intentionally, a more specific gendered analysis can be applied to question exactly why the first female president of Brazil, one who challenged the military dictatorship through her membership in radical leftist guerilla groups, like National Liberation Command (COLINA) and Armed Revolutionary Vanguard-Palmares (VAR-Palmares), was so quickly vilified in a moment of crisis.1 As Stephanie Smith writes, this analysis is “a shift from women’s history to gender as a category of historical analysis to move beyond the recognition of women’s active participation in historical events and to consider the ways in which gender identities and negotiations pervade political processes.”2

It was within the context of former President Lula de Silva’s immense popularity that Dilma Rousseff emerged. Her campaign strategy depended heavily upon her biologically essential qualities as a woman, which would carry over to her success as a female president. Once it was apparent she would be Lula’s successor, the press’ discussion of Rousseff shifted dramatically, from the occasional article noting her competency as Lula’s Chief of Staff, to overwhelming coverage that honed in on her unattractive appearance, sense of style, and lack of charisma. Headlines like “Less skin means more credibility. Showing the armpits? Never . . . The blazer shows seriousness, but the ones she uses are too short, they accentuate her hips.” and “Body and Soul 2010. With diet, plastic surgery, and a radical change to her haircut, Dilma Rousseff shows the (good) results of her own PAC, a Plan for Cosmetic Improvement” saturated the press before and after her makeover.3 Her campaign decided that, because they could not avoid press related to her appearance, they would instead embrace her femininity and exploit her made-over, softer exterior to win the election. This is when her nickname, the “Mother of Brazil” became more prominent. In a campaign speech, Rousseff proclaimed, “I want to do, with the caring of a mother, everything that still needs to be done. This is my dream.” 4 Santos and Jalalzai explain, “this gendered aspect of the campaign is used in connection to one main theme: the continuation of widely popular outgoing president Lula.”5 The Workers Party continued to promote their image as the party of reliable caretakers, led by the Father (Lula) and Mother (Dilma). This explicit tie between Lula and Dilma is an interesting one to consider. Santos and Jalalzai write that Rousseff is the only female ruler in Latin America to have been elected without explicit “family ties to power.”6 It is significant that the campaign was driven to establish fictitious family ties between her and a powerful, popular male leader. The gendered emphasis in election coverage is typical for most female candidates, no matter their country of origin; in the Brazilian case, it became especially important because it provided another distraction for the press to latch onto during the impeachment crisis. This gendered coverage became another way to reinforce conservative values.

The first years of Rousseff’s presidency were relatively hopeful, as the PT remained immensely popular nationwide. Emir Sader wrote in NACLA in 2011, “The Rousseff government has inherited not just a country in much better shape than Lula did eight years ago, but also a weakened, demoralized, and defeated right-wing.”7 The Growth Acceleration Program, PAC, of which Rousseff was declared to be the Mother, continued to be protected from adjustments of the budget and was a central part of her poverty alleviation platform. Within her first one hundred days, she pledged further funding toward public health and to pursue investigation into cases of torture under the dictatorship, to which she has a personal connection.8 Additionally, in the beginning of her presidential career, she was praised for consolidating an image as a serious leader and one who was tough on corruption.9 However, the general consensus regarding Rousseff’s first term, regardless of the material gains the PT won for working people, the works she did to further Lula’s legacy was inadequate, particularly to resolve deeper inequalities. “PT mandates around women’s health and safety demonstrated the party’s progressive approach to gender in Brazil, but did not go far enough.”10 Relatively deficient social policies, combined with an intense economic downturn at the end of Rousseff’s second term, in which growth slowed to 1% in 2012 and was stagnant by 2014, meant that the PT’s popularity was no longer unerring.

The unfortunate reality of the PT, under both Rousseff and Lula, was that it did not transform Brazil’s longstanding problems with clientelism and other antiquated practices that plagued its political system. Perhaps one of the most striking failures of the system of participatory democracy, inaugurated with the 1988 constitution, was the continued insistence of the PT to compromise with oppositional parties. Sean Purdy writes, “In the name of ‘governability,’ the PT forged dubious alliances with elements of the opposition-dominated Congress, who were all too eager to put their hands on the till of government largesse.”11 PT politicians continually fell victim to corruption charges and, more importantly, they did not offer any legitimate alternative to the neoliberal order which the opposition embraced. Brazil’s “low-to-medium” threat to neoliberalism was not strong enough to ward off conservative critics while facing an economic crisis and an outpour of popular discontent.12 Rousseff appointed Joaquim Levy and Katia Abreu, a neoliberal economist and agribusiness leader, respectively, to her second cabinet. Voters viewed these appointments as a distinct betrayal against the program of the Left.13Her increasing conformity and embrace of neoliberalism as a potential solution to Brazil’s economic woes alienated the rest of her supporters and, ironically, allowed Right to push even more intensely for conservative neoliberal policies as they responded to the anger of the white, middle class, international bourgeoisie, and the hatred the lower and working classes had for corruption.

The 2013 public transport fare-hike protests were eventually co-opted to express anger over the policies of affirmative action and increased contact with lower income people and people of color. The protests were originally led by working class students and the informal labor sector, groups traditionally backed by the PT, and were mostly due to low quality of public services (like transportation) in the wake of exponential spending and improvement for areas that would house the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympics. The second phase of these protests included the middle class, who resented the increased accessibility of spaces like universities, malls, and airports which had been “long dominated by Brazil’s white upper crust.”[14.Ibid., 218.] The middle class suffered during the slowdown of the economy and resented the apparent material improvements the working class experienced at their expense. Armando Boito and Alfredo Saad-Filho write, “Gains favoring the poor have transformed the country’s pattern of demand and, correspondingly, a whole host of institutions that used to be monopolized by the (white) upper middle class.”14

Additionally, Boito and Saad-Filho explain the division of the bourgeoisie in Brazil and its corresponding alliances to either the PT or the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB). The PT allied itself with a “hybrid neoliberal-neodevelopmental” bourgeois group, tied to Petrobras. The PSDB included orthodox neoliberals, who stressed the importance of international capital. Internal bourgeois employees, who worked for Petrobras, the Brazilian Development Bank, or other institutions, were well paid, but their salaries were far lower than those of the orthodox neoliberal judiciary members who functioned as “the right hand of the state.”15 These jurists, federal police, and public prosecutors, used the Petrobras investigation for their own political gain: “They ignored clues suggesting the involvement of the PSDB in similar cases, selectively leaked classified or misleading information to competing media organizations, and consistently sought to compromise the PT, especially in the run-up to the 2014 presidential elections.”16 With allies in the mainstream press, they ensured the investigation would constantly be in the headlines, and on the minds of the Brazilian electorate. The obsession with Rousseff’s legal wrongdoing and the indictment of her party in corruption charges became a clear tactic: “Agitation against corruption allows the internationalized bourgeoisie and the upper middle class to hijack popular revulsion against white-collar crime in order to smuggle in policy changes against the interests of the vast majority and to shift the relation of forces within the power bloc to their own advantage.”[Ibid., 203-204.] The conservative power bloc sought to gain power and found an appropriate path to follow.

In the wake of the 2013 protests and the 2014 Petrobras scandal, the Right gained much needed strength and was able to mobilize not only the upper middle class, but also poor and working class Brazilians through the selective attack against PT corruption. Eduardo Cunha, “an ambitious and unscrupulous neoconservative politician,” was elected as the president of Brazil’s lower house in 2015.[19.Fortes, “Brazil’s Neoconservative Offensive,” 4] As the Right mobilized its base (which hadn’t happened since the early 1960s), Cunha led the call for Rousseff’s impeachment. Although he was arrested and charged with over eleven charges of corruption, Cunha successfully produced a 61-20 Senate vote in favor of impeachment, and a 68% disapproval rating against Rousseff in the summer of 2016.17 Michel Temer, Rousseff’s former vice president, rose to power and appointed twenty-three ministers, all white and male, mostly key representatives from the evangelical Christian and agribusiness sectors, and “will oversee privatization of state assets, cuts to social programs, and restrictions on labor rights.”18 An obvious and immediate reversal of the PT governing strategy, Cunha’s platform and cabinet represented a return to conservative values and a condemnation of the project of inclusivity and participatory democracy in Brazil.

The same biological qualities that made Rousseff so electable in 2010 contributed to her indictment in 2015; this gendered coverage of Rousseff during the impeachment was another channel used by the press to disseminate conservative values to challenge the power of the Left. In the article, “Perversion and Politics in the Impeachment of Dilma Rousseff,” Muriel Emidio Pessoa do Amaral and Jose Miguel Arias Neto encourage the reader to observe the blatant misogyny that was allowed to fester throughout the impeachment. Through the focus on Marcela Temer, the wife of the would-be incumbent president, the press drew stark comparisons between what a wife and woman should and should not be. They wrote Marcela was “beautiful,” “discrete,” and “a deputy first lady of the household,” restricting her influence to the private sphere.19, Chasqui, no. 135 (August-November 2017): 63.] As the Right launched an attack on liberal values of state intervention and redistribution, they simultaneously launched another attack against female power in the political sphere.

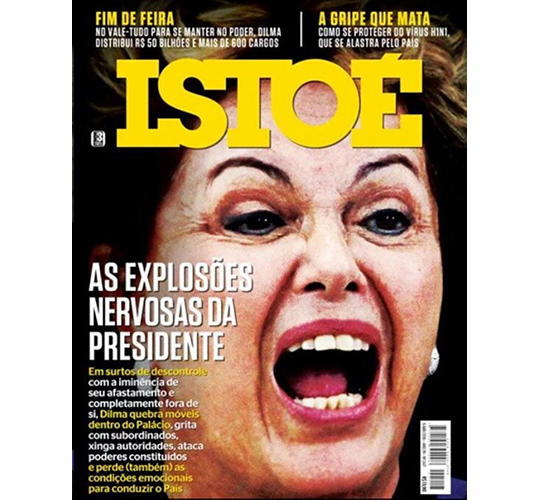

Additionally, an ISTOÉ cover spread, published in April 2016, featured an objectively unattractive, hysterical picture of Rousseff, accompanied by the title: “The President’s Nervous Breakdown [Outbursts].”20 The article, which caused a great deal of controversy, continued to detail Rousseff’s supposed loss of control, abuse of painkillers, a fluctuation between the first two stages of grief (denial and anger), complete with a “diagnosis” by a psychiatrist. The magazine is one of the three major national publications and is therefore considered a reputable source; at the very least, it is widely read. The disregard of powerful women based upon supposed mental instability is a long and painful history. The picture used on the cover, actually an image captured in 2014, during a Brazilian victory at the World Cup, was cropped, and taken entirely out of context. 21 The controversy it caused was successful in distracting the electorate. Discussions of Dilma’s mental state and capability to govern ensued; some came to her defense, aware of the intensely fraught baggage a “diagnosis” like this came with.22 In any case, a gendered critique of Rousseff’s presidency took the attention away from Cunha, his allies, and the deliberate conservative attack of the PT.

Amaral and Arias Neto present an allegorical representation of the relationship between gender and power in Brazil in their discussion of the school Fábrica de Princesas, in Belo Horizonte. Fábrica de Princesas is an etiquette school to form young girls into proper young women, where, in 2016, an instructor advised, “Princesses need to leave some things to history to change the world. Who knows [that] the future president is not here . . . Do not be like Dilma, okay?”23 The girls laughed as the instructor shared this wisdom. Amaral and Arias Neto include this anecdote in their piece to exhibit the multitude of ways misogyny was reproduced and traditional, conservative values were upheld, even in extracurricular after-school programs. The first line indicates an ideal female leader (a “princesa” in training, if you will) is passive and docile; she leaves certain matters for history to sort out. The instructor issued a warning to the young girls in her class, some of whom may have admired Rousseff in 2011: If they became too imposing, they could meet the same fate.

In her analysis of the shifting meaning of honor and sexual morality in Brazil in the early twentieth century, Susan Caulfield writes that the “paternalistic and hierarchical social order of the nineteenth century” was reproduced and “rewritten by imperial and republican jurists.”24 Moving into the twentieth and twenty-first century in Brazil, this reproduction of conservative values was still imposed by jurists allied with the internationalized bourgeoisie. Even more dangerously, this reproduction, as Boito and Saad-Filho point out, included the allyship of much of the Brazilian media which provided a distracting cover during the constitutional coup and allowed many Brazilians to dismiss the PT’s failure on the basis of Rousseff’s female identity.

Parallels between Temer’s 2015 rise and the Vargas regime takeover in the 1930s can be drawn within the framework of the reestablishment of a traditionalist ruler. (Though, Temer has yet to prove himself to be as destructive as Vargas—or, at least, as long lasting.) Caulfield wrote on Vargas’s rise to power, noting, “By exalting ‘traditional’ family values, associating them with national honor, and identifying Vargas as the father of the nation’s poor, the regime sought to naturalize centralized, hierarchical structures of authority and to ensure social order while promoting economic modernization.”25 Ironically enough, this is similar to the strategy employed by the PT during the formation of Lula’s legacy and Rousseff’s campaign. The emphasis of a familial structure of governance on both sides can potentially point to a reason why the press focused so heavily on the negative features of a female leader. When a primary class analysis overtakes the intersectionality of revolutionary inclusivity and leaves more “piecemeal concerns,” like ethnicity, gender and sexuality in the background, what kinds of harmful attitudes are allowed to arise in moments of crisis?

Many counted Rousseff’s electoral victory as a structural success for the program of participatory democracy in Brazil. Margaret Randall, writing on the Cuban laws that constitute its Family Code, tells an important story of the difference between structural changes and attitudinal shifts within a revolution. The process of institutionalization does not advance at the same pace as the mindset of the revolutionary mass. Sometimes, as in the case of Cuba or Mexico, legal transformations were surface level indicators of attitudinal shifts, while it remained more difficult for individuals to make the system work for them. Other times, as in the case of Chile, the revolutionary mass moved far ahead of the government in charge of institutionalization. In any case, it is a difficult process to perfect. While the Left is often held to a higher standard of inclusivity, it is crucial to continue to question these gaps between legal frameworks and the reliability and all-embracing quality of these frameworks. Randall writes, “The judicial repercussions of the Code, needless to say, depend on women themselves actually taking their husbands to court for violations. How many women are willing to take this step? Not enough.”26 The measures of the Family Code were extremely promising on paper. It included equal pay, equal support and a shared workload among partners. However, for women to be willing to bring the discrepancies that arose from the Code to the court’s attention, the process of consciousness building was required. At the end of the piece, Randall asserts that the true gauge of success of the Family Code would be the willingness of the Cuban people to share responsibilities at home and put the formal, legal equality into daily practice. “This will be the only way, she pointed out, that future generations will grow up with a new morality gleaned from a changed image of image of how men and women should interact.”27 Rousseff’s election and the essentialist rhetoric relied on the same kinds of sexist biases that appeared in the 2016 ISTOÉ article. Structural changes in Brazil, like the election of a female president and a larger percentage of women involved in the process of democracy, did not prevent the same patronizing rhetoric from being abused.

Regina Sousa, a PT Senator from the Northeast, defended Rousseff shortly after her impeachment:

“You veered from the narrative when you were elected president of the republic as a woman, from the left, a former militant against the dictatorship, without a husband to pose by your side in the photographs . . . You never fit in the cute little dress designed by the conservative elite of this country.”28

Rousseff’s public persona as head of state threatened traditional values. Thus, her impeachment was a twofold attack from the Right. It was not only a rejection the project of radical participatory democracy because it rewarded Leftist leaders, but that it rewarded Leftist leaders who were female.

In her address to the United Nations, in April 2016, Rousseff asserted, “In the past, coups were carried out with machine guns, tanks, and weapons . . . Today all you need are hands that are willing to tear up the Constitution.”29 Temer’s attack on democratic values needed little more than good timing and a majority willing to revive conservative values. In December 2017, a meeting between Rousseff and Cristina Fernandez of Argentina, two scorned former presidents on the Left, demonstrated an attempt to move beyond the damage done to their countries. Telesur reports, “Rousseff added that these attacks on a few political leaders was the right-wing’s clumsy attempt to hide the economic disaster neoliberal governments have created in the region.”30 The two-prong attack on Rousseff’s presidency through the convenience of corruption and her gendered identity leaves us with questions regarding the future of the Left in Brazil, and region wide, as we continue to observe the rise of right wing governments in Latin America. These questions posed in the Brazilian context are especially relevant after an appellate court upheld Lula’s corruption conviction in January 2018, effectively depleting his power to run in the upcoming presidential elections. 31 Solutions are beyond the scope of this paper; Fernandez, de Silva, and Rousseff can only hope that the pink-tide will prove its resilience, hopefully through the authentic opening of diversified spaces for female figures to occupy and govern.

- The election of female leaders generally has been heralded as an apparent marker of “progress.” I place quotations around progress to acknowledge the problematic nature of this word. It has been used inordinately to discuss “third world” or “reformed third world” nations with “backwards” or “outdated” views on gender, even by American authors and journalists who have yet to witness the election of a female president.

- Stephanie J. Smith, Gender and the Mexican Revolution: Yucatan Women and the Realities of Patriarchy (University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2014), 6.

- Farida Jalalzai and Pedro G. Santos, “The Mother of Brazil: Gender Roles, Campaign Strategy, and the Election of Brazil’s First Female President,” in Women in Politics and Media, ed. Maria Raicheva-Stover and Elsa Ibroscheva (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 175.

- Dilma Rousseff qtd. in Jalalzai and Santos, “The Mother of Brazil,” 177.

- Jalalzai and Santos, “The Mother of Brazil,” 178.

- Ibid., 167.

- Emir Sader, “Dilma as Lula’s Successor: The First 100 Days,” NACLA, March/April 2011, accessed December 16, 2017, https://nacla.org/article/dilma-lula%E2%80%99s-successor-first-100-days.

- Ibid.

- Carla Montuori Fernandes, “Dilma Rousseff e a mídia internacional: uma análise do primeiro ano do mandato presidencial,” Revista Compolitica 2, no. 3 (July/December 2014): 228.

- Sabrina Fernandes, “Assessing the Brazilian Workers’ Party,” Jacobin, May 19, 2017, https://www.jacobinmag.com/2017/05/assessing-the-brazilian-workers-party. Accessed December 16, 2017.

- Sean Purdy, “Brazil at the Precipice,” NACLA 48, no. 2 (Summer 2016): 108.

- Cannon Barry, “Inside the Mind of Latin America’s New Right,” NACLA 48, no. 4 (Winter 2016): 329.

- Alexandre Fortes, “Brazil’s Neoconservative Offensive,” NACLA 48, no. 3 (Fall 2016): 219.

- Armando Boito and Alfredo Saad-Filho, “State, State Institutions, and Political Power in Brazil,” Latin American Perspectives 43, no. 207 (March 2016): 201.

- Boito and Saad-Filho. “State, State Institutions, and Political Power in Brazil,” 202.

- Ibid., 203.

- Rapoza, Kenneth, “In Brazil, Public Support for Ousted President Dilma Is Abysmal” Forbes, June 9, 2016. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2016/06/09/in-brazil-public-support-for-ousted-president-dilma-remains-abysmal/#5db56c7b5fe1.

- Ibid.

- Muriel Emidio Pessoa do Amaral and Jose Miguel Arias Neto, “Perversão e política no impeachment de Dilma Roussef” [Perversion and politics in the impeachment of Dilma Roussef

- Sergio Pardellas and Débora Bergamasco, “Uma presidente fora de si,” ISTOÉ (Brazil), April 1, 2016, https://istoe.com.br/450027_UMA+PRESIDENTE+FORA+DE+SI/. Accessed December 22, 2017.

- Amaral and Arias Neto, “Perversão e política,” 66.

- Ibid., 6 7.

- Amaral and Arias Neto, “Perversão e política,” 63

- Sueann Caulfield, In Defense of Honor: Sexual Morality, Modernity, and Nation in Early-Twentieth-Century Brazil (Durham: Duke University Press, 2000), 9.

- Ibid., 15.

- Margaret Randall, “The Family Code,” in The Cuba Reader, Aviva Chomsky, Barry Carr, and Pamela Maria Smorkaloff, eds., (Durham: Duke University Press, 2004), 403.

- Ibid., 405.

- Simon Romero, “Dilma Rousseff is Ousted as Brazil’s President in Impeachment Vote,” New York Times, August 31, 2016, https://nyti.ms/2c8MDJ4. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- Rousseff qtd. in Andrew Jacobs, “Brazil’s Dilma Rousseff, at U.N. Climate Ceremony, Assails ‘Coup Mongers,’” New York Times, April 22, 2016

- “Dilma Rousseff Defends Cristina Fernandez as a ‘Timeless Hero,'” Telesur, December 10, 2017, accessed December 18, 2017, https://www.telesurtv.net/english/news/Dilma-Rousseff-Defends-Cristina-Fernandez-as-a-Timeless-Hero-20171210-0011.html?utm_source=planisys&utm_medium=NewsletterIngles&utm_campaign=NewsletterIngles&utm_content=8.

- Paraguassu, Lisandra. “Lula’s Brazil presidential run in doubt after conviction upheld.” Reuters. January 24, 2018, accessed March 6, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-brazil-politics-lula/lulas-brazil-presidential-run-in-doubt-after-conviction-upheld-idUSKBN1FD0FU