“Sex dolls illustrate the close relationship between patriarchy and commodity capitalism, as they both are built on ownership and objectification.” A look at the potentials and pitfalls of the growing sex-tech industry.

Sex Dolls

Dismantling Societal Structures or Reaffirming Them?

Sex dolls and robots are creating controversy around the globe, with advocates proclaiming they have therapeutic benefits, while critics argue that they are detrimental to society. Although they are a relatively recent phenomenon—with their technological conception as recent as the late 1990s—the forces that created them are not. Hyper-capitalist patriarchal norms, alongside the encroachment of commodified consumption into every aspect of society have led to the expansion of the sex-tech industry. In their current form, sex robots objectify the human—and most often female—body and can be dangerous to society. However, by using notions of cyborg feminism and transhumanism alongside social movements advocating for equality and respect for all members of society, sex robots could help to dismantle current binaries, reshape current societal structures, and create more equitable and respectful consumption and production.

The role of these dolls and the outcomes on society have spurred a heated debate. On one hand, there is the Campaign against Sex Robots, which was started in 2015 and advocates for their destruction, while there is also The International Congress on Love and Sex with Robots, a yearly conference in its fourth iteration, which investigates and reports on technological improvements and potential uses of sex robots. David Levy, a British artificial intelligence engineer, predicts that sex robots will have positive benefits, arguing, “many who would have otherwise have become social misfits, social outcasts, or even worse, will instead be a better-balanced human being” through connection with these dolls.1 Meanwhile, Ross Douthat, an opinion writer for the New York Times, argues that one-way sex dolls could be utilized is as a sort of sexual redistribution for

“the overweight and disabled, minority groups treated as unattractive by the majority, trans women unable to find partners and other victims . . . of a society that still makes us prisoners of patriarchal and also racist-sexist-homophobic rules of sexual desire.”2

However, the vast majority of sex dolls currently on the market are modeled after a specific and sexualized form—cis-female bodies—which perpetuates the disproportionate objectification of these bodies. Kathleen Richardson, the founder of the Campaign against Sex Robots, questions the ethics of this technology, correlating the possession of sex dolls to slavery, since bodies are being owned and utilized for others’ personal gain. Richardson does not view the encounter as a mutual experience because the experience rests on the idea that women are property.3 Similarly, Rashida Jones, in her 2015 documentary, Hot Girls Wanted, expands on these notions, arguing that pornography reinforces negative, oppressive, and patriarchal mindsets and expectations.4 Richardson takes the critique a step further by arguing that “their use is just contributing to and elaborating on the idea that you can relate to an object like you relate to another person, and in turn, that you can treat a person like an object.”[5. Catherine Bennett, “Sex-Doll Brothels? Tacky, Yes, but Better than the Human Version,” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, March 25, 2018. www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/mar/25/sex-doll-brothels-thriving-customers-prefer-an-object] Commodity culture is rooted in the promise that one can find self-fulfillment and happiness through external things, but Richardson and Jones pose the question: at what cost?

Sex dolls and robots are a product and extension of the hyper-capitalist patriarchal society that is present today. The tech industry is male dominated, and perhaps this is why technologies coming out of that industry are dehumanizing and objectifying, since they are reflections of our contemporary state of being. Sex robots epitomize patriarchy, as they offer men not only dominance within social and sexual situations but also the complete control over another body. They also act as a possible solution to the threat of female independence. The robots facilitate one-sided sexual pleasure and will not challenge anything that the user says or does to them. In response to increased female autonomy elsewhere in society, sex robots offer complete subordination. They are “humanoids” created for men’s sexual use. Dolls are even programmed to say things like “my primary objective is to be a good companion to you,” and, critics claim that this dynamic is purely about the male user’s need for dominance.5

Shaped by hyper-capitalist patriarchal values, our society is a commodity culture. A commodity is a good, service, or experience, that can be priced and placed on the market. Sex dolls are not only a good, but they satisfy a desire and provide an experience, so these manufactured bodies are literal aggregations and embodiments of a commodity. The production of imagery, in this case over-sexualized female bodies, is important to the success and hence the production and distribution of this commodity. In the age of hyper-capitalism, reality is essentially up for sale through a regime of continuous consumption. Jean Christophe Agnew argues that through this age of hyper-capitalism, there is corporate capture of every aspect of society. He explains that throughout people’s lives, they perform continuous cost-benefit analyses that are “so recurrent that the habitual arithmetic becomes part of our personality and comprises the very style of our being and behavior, forming what we may call our principles or tastes.”6 This encroachment of commodified consumption into every sphere of life manifests even in the most private circumstances, like someone’s sexual expression. The traditional longstanding distinction between private and public is being eroded. With sex dolls, there is no longer the need to enter into the public sphere and engage in a prostitution transaction with another human; instead the experience can be had in seclusion and without the consensual agreement between two parties. Concurrently, however, there is the formation of sex tourism with these robots. For instance, Barcelona has “become home to Europe’s first sex-dolls agency,” Lumi Dolls, with a session costing around 120 Euros per hour, while Paris is home to a sex doll brothel called Xdolls.7, 8

Sex dolls illustrate the close relationship between patriarchy and commodity capitalism as they both are built on ownership and objectification. In addition, the conception of sex dolls showcases gender and class structures and how they require economic and social power. The female is a powerless and subservient figure, while the males are the ones who reap the benefits. Luce Irigaray discusses women’s treatment as commodities when she writes,

“Women-as-commodities are thus subject to a schism that divides them into categories of usefulness and exchange value; into matter-body and an envelope that is precious but impenetrable, ungraspable, and not susceptible to appropriation by the women themselves; into private use and social use”9

Women are integral to the foundation of society through specific, gendered roles such as in reproduction, yet are simultaneously repressed, minimized down to a means of creating value and profit for other people, i.e., mainly men. Women are exploited; their labor is needed, but their value is erased resulting in an unequal distribution of profits.

In order to change production and consumption patterns to become more equitable and respectful, female voices should be included in the discussion, however, this is challenging, as the tech industry is male dominated, which creates a loop of patriarchal thought processes and consumption. Female sexual expression has traditionally been seen as quite controversial and sex toys aimed toward female pleasure were not taken seriously enough by male engineers and businessmen, so various women have decided to join the sex-tech industry in order to create pleasurable sexual products by women for women. Although much progress has been made over recent years, still only thirty percent of sex-tech businesses were owned by women in 2017, and, of those, many struggle with gaining adequate resources and exposure.10 According to Hallie Liberman’s Forbes article on the history of sex-tech companies, it is particularly challenging for women to get start-up money, and it is difficult to advertise their products since influential websites such as Facebook and Google have banned ads for sex toys.11 Although this ban effects male-owned sex-tech companies as well, it makes it harder for these newer companies to break into the already established market.

From current consumer statistics involving sex robots, it is evident that women want different products than men. For instance, RealDolls, one of the largest manufacturers, reports that “less than 5% of doll customers are women even for the small range of male dolls.”12 This illustrates how only a small percentage of women engage with these dolls, alluding to the fact that most women choose different means of sexual gratification. In comparison, a 2016 study from the University of Duisburg-Essen found that “40% of the 263 heterosexual men surveyed said they could imagine buying a sex robot for themselves now or in the next five years.”13 These statistics show how there is a sharp divide between men and women and their interest in these dolls. Despite the challenges to gain traction and acceptance in the sex-tech industry, many women are getting involved and becoming resourceful in order to “change attitudes towards sexuality and, in the process, to change the world”14 For instance, Dame became the first sex toy company to receive funding through Kickstarter, while women in the industry have created a community called “Women of Sex Tech” rooted in activism, support, and engagement.15 Dame is among other new women led sex-tech companies such as Unbound, which sends subscribers a box of products quarterly, House of Plume, which sells elegant storage boxes for sex toys, and Sustain, a company focused on making all natural sexual products. These companies are hoping to create a “female-led women’s sexuality movement.”16 These female creators are making different types of sexual toys, products based on negating objectification and reclaiming one’s own sexuality and pleasure. Their toys serve a functional purpose but do not mimic human anatomy or personhood, compared to the various male-led companies that produce sex dolls and robots that are more concerned with aesthetics and objectification. However, despite these differences, both facets of the industry essentially have the same mission. They are both innovating ways to expand and challenge the current sexual landscape.

Although the creation of sex robots seems grotesque and unnatural to some, it is important to point out that there has been a historical fascination with creating an ideal lover being, and that other forms of human-nonhuman connection are already accepted today. The most notable examples of human-nonhuman love stem from Greek mythology. For instance, Pygmalion created an ivory statue named Galatea, with whom he fell in love, while Laodamia became so attached to a bronze sculpture that she killed herself when it was destroyed. Outside of Greek mythology, human-nonhuman connection has existed for thousands of years whether that be through dolls, figurines, or even animals. Despite historical intrigue and emotional dependence on non-humans today, society is very much still stuck in the realm of human-human romantic and sexual relationships. An area of current critique stems from the belief that non-humans’ agency in such a relationship must be falsified, a mere projection by the human. In the case of sex dolls, the dolls appear to be women with agency, as they mimic and stimulate movements and thoughts like a real being, but in reality, they are just performing this consent and have been manufactured specifically for a man’s pleasure. There is the guise the doll’s participation being an active choice; however, it is not. Such a construction of agency is not universal; belief systems rooted in animism posit objects such as plants, creatures, and even inanimate objects possess a distinct spiritual essence, so it’s possible that the patriarchal subject-object dynamic currently seen between consumers and sex dolls could be open to change.

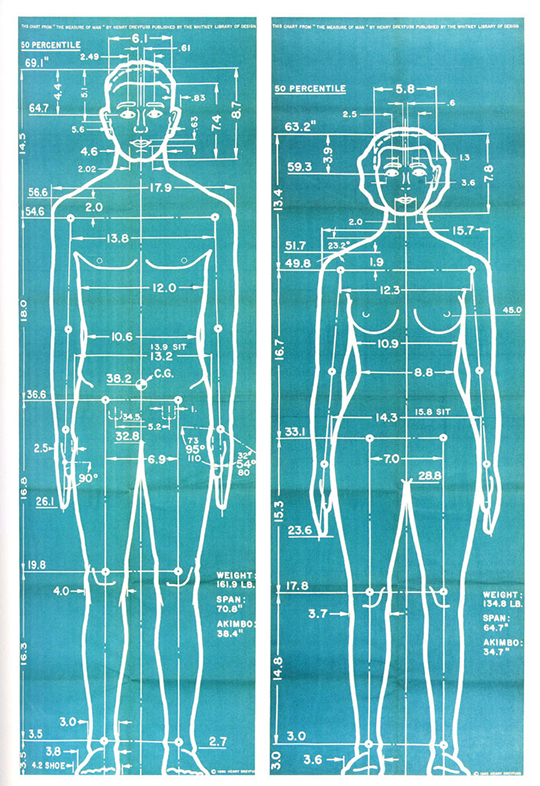

If a sex doll replicates the human body, but is not human, then questions about what a body is and can be arise in their construction. Currently a body is most often classified by specifications like gender, race, weight, age, and ability. Embodiment is also constituted by having particular body parts, such as a head, torso, neck, arm, foot, etc, but what it means to have a body and to be a human must be broken down and explored. This current conception relies on stereotypes and assumptions, which is dangerous as it places violence onto bodies as we know them. Sex dolls currently on the market tacitly affirm some of the most limiting and harmful ideas about what a body is with their overly sexualized and generally homogenous slender figures. Their figures are influenced by what is deemed worthy and admirable by society, but bodies should not need to fit under the parameters of Henry Dreyfuss’s Joe and Josephine, anthropometric charts of the “average” person, to be considered worthwhile. In Western cultures like the United States, things tend to be classified in terms of objecthood, so measurements and boundaries matter in schemas of western classification, but thinking of bodies through a lens of encounters will allow for a more accepting and free conception of what a body is and can be. As these product producers try to challenge and reshape the sexual landscape they also have the opportunity, if they choose, to combat vast inadequacies with current classifications by questioning the notions of what a body is and what is means.

Resolving this problem does not mean that there needs to be more inclusive standards for bodies and sexuality, but rather getting rid of a normative conception all together. For Spinoza, “bodies are constituted not by predefined classifications but by encounters with material, social, and spatial forces,” meaning a body is not defined by what it physically is, but how it relates to the world around it.17 Lambert and Pham expanded on Spinoza’s concept, arguing that there should not be a conception of what a body is or what a body is not, rather, bodies in whatever way they are should be able to exist freely and without confinement:

“to not know what a body isn’t means that the idea of the body is infinitely open, rather than just momentarily open. To not know what a body isn’t means that all bodies are equally valid modes and forms of embodiment. Nothing is “not a body” and so everything is a body.” 18

Currently, there is not only the anthropomorphizing of objects, but the objectification of humans through plastic surgery. Sex robots are getting to a point where the humanoid is so realistic, it cannot be distinguished from a real woman, while Valeria Lukyonova, a woman from Ukraine, has made herself into a living doll through plastic surgery and is referred to as “Human Barbie.”19,20 If one no longer appears to be fundamentally human, and an object appears to be human, where is the distinction, and why does it matter? Lukyonova’s example helps to illustrate how there needs to be a discussion and a broad change in the conception of what is considered a body, what is considered alive, and what is considered a valid form of self and sexual expression. As humans evolve and move toward a posthuman world—or at least posthuman in the way that word is currently conceived—they are able to create their own personal inventive realities. In The Next Evolution: The Constitutive Human-Doll Relationship as Companion Species, Deborah Blizzard writes,

“the doll becomes less a doppelganger or simulacra than a separate engaging entity . . . the doll is the unconventional, yet nevertheless real experience . . . regardless of how others view the doll, it is the owner’s or utilizer’s view of the dolls that make them real and worthy.”21

In other words, it is the interaction and engagement between these different entities that creates and forms a true experience. Donna Haraway theorizes on human-nonhuman relationships when she writes,

“we are, constitutively, companion species. We make each other up in the flesh. Significantly other to each other, in specific difference, we signify in the flesh a nasty developmental infection called love. This love is a historical aberration and a natural-cultural legacy” 22

Here, Haraway is urging the reader to think of love as being naturally engineered and difference being historically pleasing.

Although the current trend of hypersexualization and objectification within sex dolls is dangerous, if done correctly, sex dolls could potentially help shift our current perceptions of gender relations and the notion of “natural” sexual experiences into something more inclusive for all. Instead of reaffirming current societal structures, they could help to question and reshape them with the help of transhumanism, cyborg feminism, and accompanying social movements. Transhumanism is the belief that humans can and will evolve past our current mental and physical limitations with the ever increasing development of science and technology. Over time, features will integrate and bodies will transform into new and different configurations combining natural and living organisms with synthetic and technological material whether that be via advances in human biology or different kinds of high-tech appliances and accessories. Transhumanism, which is rooted in changing the conception of a humanly body, cannot fully happen without cyborg feminism, which in its simplest form, is the breaking down of binary limitations on things like gender, feminism, sexuality and even the difference between “natural” and “artificial.” Deborah Blizzard when reflecting on Donna Haraway’s classic work, The Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology and Socialist Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century pushes the reader to conceptualize the world as currently exhibiting “the dangers of dichotomous thinking nurtured in paternalism and historical inequality and to a world beyond traditional bodies: bodies of flesh, bodies of politics”23 The fictive figures of cyborgs in narratives attempt to question and stretch boundaries and aim to subvert traditional racial, gender, and able-bodied stereotypes, however they do not always succeed. Sophie Wennerscheid quotes Anna Balsamo in her article Posthuman Desire in Robotics and Science Fiction saying, “the cinematic image of cyborgs might suggest new visions of unstable identity, but often do so by upholding gender stereotypes. To this end, we need to search for cyborg images which work to disrupt stable oppositions.”24 Alongside this ever-expanding technological landscape, there need to be accompanying social movements pushing these advances towards a more inclusive and equitable reality. Social movements need to guide this development away from an intrinsically patriarchal power structure to one that works for all of society.

The transition into being ineradicably connected with technology has already begun, so humankind needs to decide whether to use this development to spur larger change or let it continue to exacerbate current inequalities. Society is currently rooted in a way of life that revolves around capitalistic patriarchy and commodified consumption. This structure is not inclusive nor beneficial to all. Although sexual connection with an inanimate object may seem bizarre to some, accepting this reality can help liberate others from various kinds of binary driven oppression. However, as previously mentioned, social movements rooted in inclusivity and acceptance must be active as this technology develops, or else these developments could result in intensified binaries and oppression. Having emotional and sexual connection to nonhumans is not new, nor will this notion be going away anytime soon, as the conceptions of what bodies and humans are will continue to change and fluctuate as society moves towards a posthuman world and hopefully adopts notions of transhumanism and cyborg feminism.

- Jenny Kleeman, “The Race to Build the World’s First Sex Robot,” The Guardian, April 27, 2017. www.theguardian.com/technology/2017/apr/27/race-to-build-world-first-sex-robot.

- Ross Douthat, “The Redistribution of Sex,” The New York Times, May 2, 2018. www.nytimes.com/2018/05/02/opinion/incels-sex-robots-redistribution.html.

- Sophie Wennerscheid, “Posthuman Desire in Robotics and Science Fiction,” Love and Sex with Robots, ed. David Levy, (Springer International Publishing, 2018), 37–50.

- Hot Girls Wanted, Directed by Jill Bauer and Ronna Gradus (Two to Tangle Productions, 2015).

- Meghan Murphy, “Sex Robots Epitomize Patriarchy and Offer Men a Solution to the Threat of Female Independence,” Feminist Current, April 28, 2017. www.feministcurrent.com/2017/04/27/sex-robots-epitomize-patriarchy-offer-men-solution-threat-female-independence/

- Agnew, “The Give-and-Take of Consumer Culture, 19.”

- Cecilia Rodriquez. “Sex-Dolls Brothel Opens in Spain and Many Predict Sex- Robots Tourism Soon to Follow,” Forbes, June 1, 2017.

- Bennett, “Sex-Doll Brothels? Tacky, Yes, but Better than the Human Version”

- Luce Irigaray, “Ch.8.: Women on the Market,” This Sex Which Is Not One, trans. Catherine Porter and Carolyn Burke (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985), 176)

- Hallie Liberman, “The Stimulating History of Sex Tech,” Forbes, October 30, 2017. www.forbes.com/sites/break-the-future/2017/10/27/the-simulating-history-of-sex-tech/#34bf715719ed.

- Liberman, “The Stimulating History of Sex Tech.”

- Murphy, “Sex Robots Epitomize Patriarchy.”

- Bennett, “Sex-Doll Brothels?”

- Liberman, “The Stimulating History of Sex Tech.”

- Anna North, “Women of Sex Tech, Unite,” The New York Times, August 18, 2017. www.nytimes.com/2017/08/18/nyregion/women-of-sex-tech-unite.html.

- North, “Women of Sex Tech, Unite.”

- Leopold Lambert and Minh-ha Pham, “Spinoza in a T-Shirt,” The New Inquiry, April 18, 2017. www.thenewinquiry.com/spinoza-in-a-t-shirt/.

- Lambert and Pham, “Spinoza in a T-Shirt.”

- Kleeman, “The Race to Build the World’s First Sex Robot,”

- Michael Idov, “Meet the Human Barbie,” GQ, July 12, 2017. www.gq.com/story/valeria-lukyanova-human-barbie-doll.

- Deborah Blizard, “The Next Evolution: The Constitutive Human-Doll Relationship as Companion Species,” Love and Sex with Robots, ed. David Levy, (Springer International Publishing, 2018), 114-127.

- Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003).

- Blizard, “The Next Evolution: The Constitutive Human-Doll Relationship as Companion Species.”

- Anna Balsamo in Wennerscheid, “Posthuman Desire in Robotics and Science Fiction.”