The Silver Age of Superhero Comics and How Marvel’s Spider-Man Brought it to an End

Great Power

The Silver Age of Superhero Comics and How Marvel’s Spider-Man Brought it to an End

Introduction

ZOINK! BIFF! KAPOW!

Even those who have never read a comic book can usually recognize the archetypal onomatopoeias from old superhero action scenes. The tradition began in the panels, but gained much of its iconic appeal from the 1960s Batman TV show. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention.

In the summer of 1973, comic book readers saw a different application of the onomatopoeia. In issue No. 121 of The Amazing Spider-Man, the titular hero’s girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, is thrown off the Brooklyn Bridge1 by the Green Goblin, a recurring villain.2 Spider-Man moves quickly and is able to snag her ankle with his webshooter before she slams into the East River. Elated, he praises himself for a successful rescue, not privy to what the readers have just seen: a tiny word placed beside Gwen’s neck the moment he catches her—“SNAP.” 3

For many, this moment marks the end of the Silver Age of Comics, the superhero’s youthful, campy era, and ushers in the start of the more socially-aware Bronze Age of Comics.4 Arnold Blumberg, a professor at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, puts words to the thoughts of many comic book fans and historians[5. To be fair, there is a camp of people who mark the era’s end in 1968, but why those individuals are wrong is topic for a different essay entirely.] in his poignantly titled article “‘The Night Gwen Stacy Died’: The End of Innocence and the ‘Last Gasp of the Silver Age’”:

The death of Gwen Stacy was the end of innocence for the series and the superhero genre in general—a time when a defeated hero could not save the girl, when fantasy merged uncomfortably with reality, and mortality was finally visited on the world of comics. To coin a cliché, nothing would ever be the same.5

The typical comic book enthusiast will describe the timeline of the Silver Age as spanning from 1956, the introduction of DC’s Barry Allen, the first successful superhero created after World War II, to Gwen Stacy’s death in 1973.6,7 I take some umbrage with these start and end dates, the events raised as most significant, and the entire idea that the Silver Age was ever “innocent” (the world I would use is “stifled”). For reasons that will become abundantly clear, I place the Silver Age timeline from 1954 to 1971. This era of comics ends where it begins: with censorship.

I admit Blumberg and I do agree on one thing—Spider-Man was definitely the catalyst.

The War on Comics

In order to better understand the Silver Age and the significance it held, it pays to provide historical context and examine the events that led to it in the first place. American comic books, superhero comic books especially, took a nosedive in the postwar years.8 During World War II, comics were the most popular type of entertainment in the United States.9 They had strong readerships among both children and adults; GIs, many of whom grew up reading comics during their first bloom in the 1930s, received them in large shipments while deployed.10,11

The reasons for their success are not difficult to spot: Comics were cheap goods in a time of rations, colorful and fun in both palette and vocabulary, not to mention a great way to stir up patriotic fervor 12,13 It also makes sense that the postwar years would be difficult for comics that could not adapt. Their go-to villain, the Nazi, was no longer as relevant, and with the economic boom, new technologies like television became serious competitors for the public’s attention.14,15 Arguably the biggest reason for the decline, though, was the country’s social and political shift.

The end of World War II turned America inside out in just a few short years. By the late 1940s, the United States had lost its longest sitting president, revitalized its economy, turned into a world superpower, experienced a massive foreign attack on its soil, and detonated a weapon no one had ever seen before.16 It stands to reason that such massive events would lead to a change in a country’s internal psyche. In a 1992 article published in the International History Review, Geoffrey Smith expounds upon this culture shift, describing early Cold War America in frank, borderline damning terms. He paints a picture of forced conformity and aggressive alienation of those who did not fit into the accepted dynamic.17 The dynamic in question was the traditional nuclear family; White, Christian, and American-born, this unit was led by a strong father able to produce a stable financial income and assisted by a caring but submissive wife who took care of the children and home.18 Smith’s main argument rests on the claim that early Cold War American culture was shaped by the nation’s obsession with keeping communists at bay both abroad and at home. Figures in the United States government such as Senator Joseph McCarthy and Attorney General Howard McGrath spoke of communism as if it were a virus—hidden in large numbers and dangerously contagious.19,20 Trials of suspected communist spies such as Alger Hiss and the Rosenbergs did nothing to ease the building tension.21,22,23

Comic book writers did not look particularly flattering under the glowing searchlight of communist paranoia. Far from the white bread, middle class “ideal” Americans that Smith describes, most of these writers were from poor immigrant families—largely Jewish families, but also Italian, Japanese, African-American, and more.24,25 For a while, this actually worked to the writers’ advantage: People were so dismissive of comics because of their association with the lower ranks of society that few saw them as a threat worth censoring.26,27 In the years following World War II, however, there was a “close scrutiny of all matter of American life . . . foreign policies of containment began to be applied domestically.”28 The industry’s influence on children became a major concern.29 Around the time McCarthy was rearing his head, there was a connected growing fear of the disruptiveness of youth culture when its members diverged from the path of social acceptability.30 Generational gaps were not a novel concept but, as Margaret Peacock points out in her doctoral dissertation, “it was not until the Cold War that these crises among the populations’ youngest demographic were portrayed as menaces to national security.”31 Like Smith, she notes that the American public feared psychological corruption as much as nuclear warfare. Psychoanalysis theory in general and psychiatrists in particular had a lot of clout at this time, and it further emphasized that people, especially children, were easily shaped and influenced by their surroundings.32,33

One of these psychiatrists, Dr. Frederic Wertham, is infamous among comic book historians.34 Wertham was not the only prolific comic book dissenter—writer Sterling North is another example, as is Catholic bishop Charles Francis Noll35—but he may have proved the most dedicated.36,37 From 1948 onward, Wertham wrote scathing articles and books against the industry.38 His magnum opus was 1954’s Seduction of the Innocent, which, among other things, accused comics of lowering the literacy rate, creating criminal habits in children, and encouraging taboo sexual behaviors such as homosexuality and pedophilia.39 His book proved extremely successful among critics and was even named the National Education Association’s book of the year.40,41 Contemporary writers, such as David Hajdu and Carol Tilley, are quick to point out that Wertham’s book is intentionally misleading, a tome of unverified anecdotes with forced analysis and absolutely no control groups or peer testing presented as a thorough scientific investigation.42,43 Tilley, who gained access to Wertham’s original notes in the 2010s, takes her claims further than most, charging him with “numerous falsifications and distortions.”44 Even Michael Goodrum, who is more sympathetic to Wertham than most historians, states Wertham and his contemporaries had a “narrow understanding of children’s literature” and at times seemed to forget entirely that comics also had an adult audience.45

Valid or not, Dr. Wertham was called up later that year to testify in front of the U.S. Senate’s televised committee on juvenile delinquency and its connection to comics.46 Dr. Wertham spoke for more than half an hour, and the Senate received him with quiet reverence.47 When it was time for comic book publisher William Gaines to testify, however, things took a different turn.48 Gaines sounds baffled that he even needs to explain himself. “[Do] we think our children so evil, simple-minded, that it takes a story of murder to set them to murder, a story of robbery to set them to robbery?” he asks.49 It is clear Gaines is only there for show; in a manner reminiscent of the House of Un-American Activities, Gaines’s subsequent questioning plays out like a kangaroo court as Senator Estes Kefauver and Chief Council Herbert Beaser interrogate him relentlessly.50,51 His testimony would nonetheless make the front page of The New York Times.52

The Comic Code Authority and Its Effects

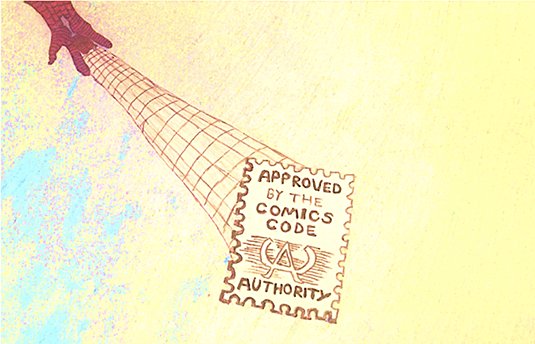

The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. They undoubtedly were aware of the Hollywood Inquisitions that took place a few years prior and had no desire to be blacklisted or arrested like so many actors and artists.53,54 Their solution was to create a self-imposed censorship that would put the Hays Code to shame, a series of regulations stricter than even the government would dare push.55 Detective Comics and its fellows still in publication, established the Comic Magazine Association of America, which in turn laid out a set of rules that came to be known as The Comic Code Authority, henceforth referred to as the CCA.56,57 Some of the CCA’s rules seem logical, if a bit conservative: a requirement that female characters be “drawn realistically without exaggeration of any physical qualities,” no “unnecessary” gore, no attacks on religious or racial demographics,58 no profanity, et cetera.59 Others—the vast majority, in fact—seem needlessly restrictive: good must always defeat evil, crime cannot be made compelling nor criminals sympathetic in any way, authority figures cannot be “presented in such a way as to create disrespect,” no “excessive use” of slang, no “abnormal” romance permitted, and “special precautions” must be taken “to avoid references to physical afflictions or deformities.”60 There were specific bans on vampires, werewolves, ghouls, and zombies, and the use of certain words in titles, such as “crime” and “horror,” were likewise forbidden. The CCA also includes an all-encompassing blanket statement that grants the censors virtually unlimited power: “All elements or techniques not specifically mentioned herein, but which are contrary to the spirit and intent of the code, and are considered violations of good taste or decency, shall be prohibited.”61

The implementation of the 1954 Code was the final strike in what had already proved a momentously difficult year for comics; its effects on the industry were so immediate, so dramatic, and so all-encompassing that it seems unfitting to peg any other time period as the start of the Silver Age. In two years, the already declining superhero industry halved its sales, which at this point consisted only of Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman.62,63 Other comic genres such as romance and horror were initially able to keep an audience in the late ’40s and early ’50s, but after the Code’s publication their subject matter alone rendered them unsalable.64 “If a book didn’t have a Comics Code seal, distributors wouldn’t touch it,” Sean Howe explains in his book on the history of Marvel.65,66

The new restrictions severely limited what kind of stories could be told and comics found themselves marketing almost exclusively to children once again.67 By the time Barry Allen made his debut two years later, the world of superheroes was already in a new age, warped beyond anything its 1940s incarnation would recognize. Unlike other comic book genres, superheroes were able to adapt. The main change other than audience was genre; superhero comics became increasingly light-hearted, with a science-fiction aesthetic and starring all-good heroes and their one-dimensional antagonists. For example, Batman, who spent the Golden Age dabbling in noir mystery and gothic fantasy, suddenly found himself going back in time, traveling through space, getting transformed by potions, and fighting a series of increasingly ridiculously campy villains.68,69,70

Along Came a Spider

It was in this atmosphere that Marvel Comics first appeared. Marvel, formerly known as Timely, first made waves in 1961 with the introduction of the team The Fantastic Four, or FF, the company’s first superheroes since the cancellation of Captain America and its other World War II stars.71,72 The characters were linked through kinship: there was Dr. Reed Richards, a scientist; Ben Grimm, a pilot and Richards’s friend; Sue Storm, Richards’s girlfriend; and Johnny Storm, Sue’s high-school-aged brother.73 In a backstory truly reminiscent of the times,74 the characters receive their powers by being bombarded by “cosmic rays” during a test flight of Reed’s spaceship.75,76 As a group, the FF were more grounded and realistic than previous heroes; they bickered and fell prey to their flaws, though they never got ambiguous enough to challenge the CCA.77 The team was envisioned and then co-plotted by artist Jack Kirby and writer Stanley Lieber under the penname “Stan Lee.”78 Lee would later recruit Steve Ditko, a more realistic and less embellishing artist than Kirby, for what would become Marvel’s most successful title: The Amazing Spider-Man.79

Peter Parker, the Amazing Spider-Man, debuted in 1962 and immediately changed the stakes of what it meant to be a superhero.80 Though Johnny Storm beats Peter as Marvel’s first young hero,81 the two are far from copies of each other. In fact, they could not be more different. Unlike Johnny, Peter has no connections, nor is he nearly as attractive and self-assured, and he is also very bitter toward most of the people around him.82,83 An orphan who lives with his elderly Aunt May and Uncle Ben, Peter does not have a conventional home life either. From his very first issue, the series seemed to be teasing the CCA, experimenting how far it could go with moral ambiguity. Peter’s powers appear in a classic enough pseudo-sci-fi Silver Age fashion—a bite from a radioactive spider—but unlike, say, the FF, who immediately vow to use their abilities to better mankind, Peter’s reaction is more natural, by which I mean selfish. His first instinct is to answer wrestling challenges and appear on TV to earn pocket money; his concern for others is so little that he does not make a move to apprehend a thief who runs past him.84 It is only when the criminal kills his Uncle Ben during a robbery that he grasps the consequences of his actions and comes to the oft-quoted realization that “with great power, there must also come great responsibility.”85 Spider-Man would continue to prove shockingly grounded with recurring themes such as insecurity, financial instability, and emotional loss.86 His constant feelings of being isolated and ostracized made him a strong metaphor for adolescence, even as the character grew older, graduating from the fictional Midtown High in 1965.87

Spider-Man was an instant hit among young readers, especially college students, who went so far as to mark the character (along with the Hulk) as a revolutionary icon.88,89 Marvel’s official fan club, “The Merry Marvel Marching Society,” had fifty thousand members in 1966 and ran out of adult-sized T-shirts.90,91 For the most part, Stan Lee embraced the growing audience. Not only did he speak on college campuses but he kept in touch with fans through letters, addressed them directly in narration bubbles, and even created special behind-the-scenes segments, like the Bullpen and Stan’s Soapbox, which made young people feel as though they were participating in the comic book process.92 Lee reinstated a level of respect to young readers that had been largely lost with the creation of the CCA.

The world was changing. Members of the baby boomer generation were growing into young adults and on college campuses, there was a surge in political activism from both the justify and the Right.93 The rigid conformism of the 1950s was fading away. Individualism was the language of the counterculture and it extended beyond long hair and rock and roll; this generation was full of people who believed they could make a direct impact on society.94 Superheroes were appealing, not for their patriotic prowess, but because they reminded readers what individuals like them could accomplish. DC was still the superhero frontrunner, but Marvel was catching up quickly even though the former had the advantage of being older, larger, and more classically professional.95 Sean Howe’s analysis that “to Marvel readers, the personalities of the DC characters were interchangeable, their lives static and flat . . . most of the DC world seemed earnestly homogenous, rendered with a polite draftsmanship that radiated a kind of complacency.96 In other words, DC was content in keeping with the McCarthy-era regulations it helped create a decade earlier. Marvel Comics, meanwhile, was building a name for itself as a company that created the everyman hero.97

By the late 1960s, Lee found himself walking a fine line. He could only extend himself so far politically. As Goodrum puts it: “Stan Lee’s main concessions in the political arena were to urge everyone to get along with each other. The main source of political engagement was then coming from readers, not writers, editors and artists.”98 Part of the limitations certainly came from Lee’s personal ideology: He was of a different generation than his readers—a Roosevelt Democrat, not a hippie.99,100,101 Another factor to consider is that until 1968, Marvel comics were legally banned from publishing more than eight titles per month, which likely made them hesitant to experiment much in controversial areas. With only a few titles to sell, Marvel could not afford to risk one eighth of their profit 102,103The primary source of tension, however, was more likely the CCA, which continued to desperately cling to its ultra conservative 1954 text. This made matters difficult whenever Marvel tried to engage with pressing issues. For instance, while Spider-Man dealt with a number of storylines involving student protests, the CCA forbade the writers from criticizing “respected institutions” like universities, the NYPD, or the United States government.104 These limitations often made Marvel’s attempts at addressing topics like the Vietnam War or systematic racism feel shortchanged, even though Peter is shown to be sympathetic to the protestors’ causes.105 Earlier comics had a lot more success conveying political messages through subtler methods, such as giving Spider-Man black classmates and coworkers.

The year 1971 marks a definitive turning point in this pattern with the publication of The Amazing Spider-Man No. 96. The issue was the first in a three-part arc called “Green Goblin Reborn!” about the dangers of drugs.106 Stan Lee had actually received the suggestion for the story from the United States Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, but there was a problem: the CCA refused to give it a stamp of approval.107 There was nothing in the issue that the CCA explicitly forbade, instead the censors drew in the blanket clause about topics “contrary to the spirit and intent of the code” and that narcotics could never be shown on panel, even when displayed negatively.108,109 Lee, who was growing both more openly political and increasingly fed up with the outdated comic censors, decided to publish the issue regardless, and despite everyone’s reservations, it sold.110 In response, the CCA quietly loosened and revised their code.111 Marvel celebrated by making its very next Spider-Man arc a body-horror-filled romp starring a villainous vampire.112 No emergency meetings of Congress were called to discuss this potentially youth-corrupting development.

Conclusion

Many writers place the end of the Silver Age of Comics at a noncommittally vague point in the 1970s. If pressed to pick a specific issue, most, like Blumberg, choose The Amazing Spider-Man #121, which features the death of Gwen Stacy. I disagree. Blumberg is correct to note that Gwen’s death had a strong narrative impact, but he fails to look at the bigger picture of why this era of comics had that narrative pattern in the first place. The defining factors of the Silver Age—everything from the whitewashed family values to the wacky trips to outer space—were either caused or influenced by the Comic Code Authority. For that reason, it is most logical to bookmark the era with the Code’s genesis and first revision. Nothing that came afterwards, Gwen’s death included, would have been possible otherwise.

Stan Lee was not initially looking to make a political mark on the world; he just wanted to write stories. Nevertheless, “Green Goblin Reborn!” made a critical statement about free speech and opened the floodgates for thousands of more nuanced and diverse superhero arcs. The 1970s grew into a booming time for comic innovation, featuring new characters from all different backgrounds and storylines that shook up the status quo.113

The industry has not slowed down since.

- Mislabeled by many, including the original text, as the George Washington Bridge, as noted in Arnold Blumberg’s 2006 article “‘The Night Gwen Stacy Died’: The End of Innocence and the ‘Last Gasp of the Silver Age.”

- Gerry Conway and John Romita, The Amazing Spider-Man, No. 121 (Marvel Comics, 1973), 18.

- Conway and Romita, The Amazing Spider-Man, No. 121, 19.

- Arnold T. Blumberg, “‘The Night Gwen Stacy Died’: The End of Innocence and the ‘Last Gasp of the Silver Age,’” International Journal of Comic Art, vol. 8, no. 1, April 2006, 197-211.

- Blumberg, “‘The Night Gwen Tracy Died,’” 199.

- Blumberg, “‘The Night Gwen Stacy Died,’”198

- Michael Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image: from War to Watergate, (London: Routledge, 2017), 103.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 79).

- David Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America (New York: Picador, 2009, 5.)

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 39-40

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 70.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 15-26

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 5, 36, 55.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 39-40

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 70.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 41, 44, 51-52, 65.

- Geoffrey Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation: Sex, Gender, and Disease in the Cold War United States, The International History Review, vol. 14, no. 2, 1992, 308, JSTOR. www.jstor.org/stable/40792749.

- Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation,” 309-311.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 65-66

- Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation,” 312-313.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 65

- Margaret E. Peacock, “Contested Innocence: Images of the Child in the Cold War,” (PhD diss. University of Texas at Austin, 2008), 113

- Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation,” 315.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 16-17

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 25-26, 42, 55, 67-68.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 27-28

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 35, 47.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 65.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 73.

- Peacock, “Contested Innocence: Images of the Child in the Cold War,” 7.

- Peacock, “Contested Innocence: Images of the Child in the Cold War,” 7.

- Robert Genter, “‘With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility’: Cold War Culture and the Birth of Marvel Comics.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 40, 16 Nov. 2007, 959. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5931.2007.00480.x.

- Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation,” 310.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 66.

- Catholic institutions were some of the most vocal early comic book critics. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses (116-119, 303).

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 40-41, 75, 230-231

- C. L. Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics,” Information & Culture: A Journal of History, vol. 47 no. 4, 2012, 348, Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/lac.2012.0024.

- Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent,” 389.

- Fredric Wertham, Seduction of the Innocent, 2nd ed. (New York: Rinehart & Company, Inc., 1954), 125-126, 150, 190-192, via www.scribd.com/doc/30827576/Seduction-of-the-Innocent-1954-2nd-Printing.

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 242-243.

- Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics,” 384.

- Hajdu, The Ten-Cent Plague, 232-233

- Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics,” 386.

- Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics,” 386.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 44, 51.

- Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications That Helped Condemn Comics,” 384.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 90.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 90.

- US Congress, Senate Committee on the Judiciary, Juvenile Delinquency (Comic Books), 83rd Congress, 2nd session, 1954, 98. archive.org/details/juveniledelinque54unit.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 90

- US Congress, Juvenile Delinquency (Comic Books), 99-109.

- Sean Howe, Marvel Comics: the Untold Story (New York: Harper Perennial, 2013), 30.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 91

- Smith, “National Security and Personal Isolation,” 317.

- Sean Howe, Marvel Comics, 31.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 31.

- Tilley, “Seducing the Innocent,” 385.

- This seems like a good addition on the surface, but to comic writers it quickly became evident that the CCA was attempting to rule out not just prejudice, but minority characters altogether. A key example of its implementation occurred in 1955 when the censorship prohibited the republishing of a 1952 comic because it featured a black astronaut (Hajdu, 321-322).

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, “The Comics Code of 1954,” http://cbldf.org/the-comics-code-of-1954/.

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, “The Comics Code of 1954.”

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, “The Comics Code of 1954.”

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 101.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 31.

- Peacock, “Contested Innocence,” 128-129.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 31.

- Howe explains that Gaines got around the CCA by turning to magazine writing, since magazines were considered a different medium and therefore not held to the code. This is how Mad Magazine began. (Howe, 31.)

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 44, 99-101.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 2

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 62-63, 77.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 69-70.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 2-3

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 77.

- Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, Fantastic Four. No. 1 (Marvel Comics, 1961), 9-10.

- In fact, as the comic was in production, the USSR sent the first human into space, Yuri Gagarin (Howe 38).

- Jack Kirby and Stan Lee, Fantastic Four. No. 1 (Marvel Comics, 1961), 10.

- This kicked off Marvel’s long and rich relationship with the All-Purpose Radioactive Plot Device, another sign of the times.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 38-40.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 3.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 41.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 108.

- Discounting World War II era sidekicks like Toro and Bucky Barnes.

- Howe 41-42

- S. Mondello, “Spider‐Man: Superhero in the Liberal Tradition,” The Journal of Popular Culture, X (1976), 232. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1976.1001_232.x.

- Steve Ditko and Stan Lee, Amazing Fantasy, No. 15 (Marvel Comics, 1962), 4-8.

- Ditko and Lee, Amazing Fantasy, No. 15, 9, 11.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 42.

- Steve Ditko and Stan Lee, The Amazing Spider-Man. No. 28 (Marvel Comics, 1965), 17.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 111.

- Mondello, “Spider‐Man: Superhero in the Liberal Tradition,” 233.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 19.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 4-5.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 4, 44, 60, 90.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 17-19.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 17-19.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 68-69.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 68-69.

- Genter, “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” 17-19.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 139.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 139-140.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 93.

- Mondello, “Spider‐Man: Superhero in the Liberal Tradition,” 236.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 141.

- This is why a lot of Marvel’s early minority characters tended to appear in already established titles. For example, Black Panther, first introduced in 1966, spent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four (Goodrum 122; Howe 70).

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 138-140.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 96.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 170-171.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 169.

- Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, “1954 Comics Code”

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 170.

- Howe, Marvel Comics, 112.

- Goodrum, Superheroes and American Self Image, 167.

- Gil Kane, Stan Lee, and Roy Thomas, The Amazing Spider-Man, No. 101 (Marvel Comics, 1971).

- Perhaps most notably, the ever-patriotic Captain America became disillusioned with the United States government under President Nixon and temporarily gave up his title (Goodrum 205-207).