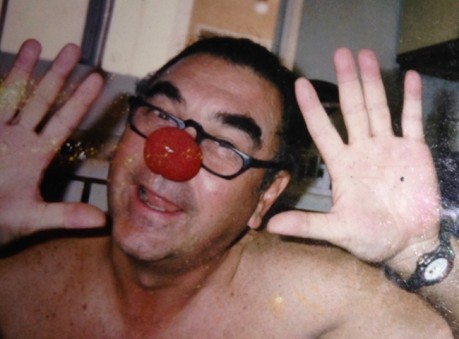

“My dad. He’s funny when he doesn’t try to be and funny when he tries.” Portraiture.

“You-Mor”

“It smells like oatmeal in here.” This is what I said one day when I came home from high school.

“Opium? Opium?! How does she know what opium smells like?”

My dad. He’s funny when he doesn’t try to be and funny when he tries.

To this day, I don’t know what opium smells like, but I have a feeling he does.

He’s tall, though his parents and brothers were all rather small.

“Just stretch yourself. Hang from the banister there, and you’ll be taller. That’s how I did it!”

I don’t know how he did it, but I don’t believe him. I didn’t grow any taller, and my friends would laugh when I told them about my stretching.

For as long as I’ve known him, my dad has had a big potbelly. I hear he was once very slim, which is believable because his legs are still quite lanky, but potbellies are good for hugs, so it doesn’t really matter to me anyway.

When he’s not working or going out for a special occasion, he wears the same thing—black cotton pants and a black cotton shirt with a pocket on his upper left side. The shoes change, but the pants and shirt are staples.

Despite having lived in Los Angeles since 1976, there are little elements in his speech that remind me that he was born and raised in New York.

“You-man” “Q-wor-ter” “a glass of w-or-ter”

Frank Cavestani was born in Flower Fifth Avenue Hospital which was located on 105th Street in New York City, right off Central Park. April 24, 1943. It was a Saturday, the day before Easter—Holy Saturday.

“I remember my birth vividly. I was a mess, crying loudly. I also had a black eye said to have been caused by one of my mother’s ribs. Yeah, right! I was pissed. However, everybody seemed very pleased to see me. I found the whole experience embarrassing, and still do, often avoiding birthday celebrations because of that first awful experience.” His voice is smooth and lyrical— and he’s the best storyteller I know. His eyes light up, fully reimagining moments as he retells them.

He was the youngest of three boys, all of whom were six years apart from one another. There were Joe, Bill, and Frank.

He and his family lived on Amsterdam Avenue and 103rd Street, one block away from Broadway. They could smell the Hudson River from their two-bedroom “train car” apartment.

He tells me he called it such, “because it had a door at either end of the apartment that was laid out like a large train car. You could enter the front into the kitchen dining area, make a right pass one bedroom, mom and dad’s, down a short hall, pass the bathroom and closets, enter a second bedroom, then a living room that opened onto Amsterdam Avenue where the traffic noises stemmed from five stories below. If you wanted to, you could exit the apartment to the staircase and hall through a second rear door, like a train.”

The hallway had clean marble and metal banisters and steps. The walls were made of yellowish large bricks said to be fireproof.

“I liked them because they were smooth and always cool. There were a few nifty secret hiding places in the hallway where my brothers and I could leave messages and hide long things like stickball bats, and forbidden things like matches, firecrackers, or cigarettes.”

In the rear yards of the apartment were trees of a “strange sickly smelly type” that were fenced off with warped, unpainted wooden fences. From the back window, if you stood on the fire escape, for as far as you could see were tall wooden telephone-type poles that hung white clothes lines from almost every window. “I’m talking hundreds of lines.” “Clothes line alley” his mother jokingly called it.

His mother was born in Hell’s Kitchen on 51st Street on the West Side. She told him of World War I, and how the wounded men from the ships and the war in Europe were driven in horse-drawn wagons down her street on the way to the French hospital on 8th Avenue. Her father was a mailman; “a big, tough, hard-drinking Irishman,” my father says, called Tully. He was married to a Connelly. Most of his young life, my father was surrounded by Irish men and women—he felt Irish, though his dad was Spanish and Filipino.

My dad used to tell me that his mother was a leprechaun. I had seen photos of her—she looked nothing like my dad, flame-red hair and green eyes. I thought the lack of resemblance just meant that she was magical, a real leprechaun in the family.

Her words were powerful.

“Frankie, whatever you do, never lose your sense of humor,” she told him after he was drafted for the Vietnam War. These were the words that kept him sane—a lot of people had lost themselves in Vietnam.

He was drafted at the age of 24, leaving his life at the American Academy of Dramatic Arts, where he had a scholarship, and abandoning the Broadway plays and television shows he was participating in at the time. It was no surprise that he was involved in theatre, considering that his father, Joseph Cavestani, born in the Philippines, jumped ship as a nubile seaman while coming to America in 1917 and somehow wound up in Los Angeles as an extra in Hollywood movies. My dad’s father worked at the Copacabana Club, one of the most famous night clubs in the world, and visiting his father there while growing up did greatly influence his young life.

“When he was still alive, years ago, and visiting me in Los Angeles, he pointed to an old building and said he used to go there to play pool and hang, but had to run one day when the Immigration came in.” It was later that he became a citizen—my dad has seen the papers.

“The fact that he was born in another country and late to be a citizen is one of the reasons I didn’t fight the draft, and I ended up willing to serve and possibly die in the Vietnam War.”

Regardless of initial pride, it didn’t take him much time to realize that the Vietnam War was unnecessary. When he came home in 1968, he fought hard to help stop the war. He made a documentary about his friend, Ron Kovic, and their experiences in the war, which later inspired Oliver Stone to make his film Born on the Fourth of July starring Tom Cruise.

Soon after he came home from the war, he was acting again. He was living at the Chelsea Hotel and hanging out with Andy Warhol at Max’s Kansas City on 18th and Park Avenue.

“I was also at Woodstock,” he tells me. “And I’m also in the documentary film of Woodstock next to my heroine (pun, but true) Janis Joplin.” 1969. He was twenty-six years old (and did a hell of a lot more drugs than I have).

He used to tell me of all his old girlfriends, how he was still friends with a lot of his high school sweethearts, and how the nuns at his Catholic high school used to have crushes on him.

“I swear, I’m telling you, this teacher of mine, a nun, had a crush on me. She couldn’t be in the same room as me! They told me if I just went to the library during that class time, I could still get a passing grade.”

Eventually he settled down after meeting my mom in a theatre company in Los Angeles called Theatre East.

I grew up with my parents watching lots of movies. They let me draw all over the coffee table so I could “express my creativity.” They’re a little wacky (in the best way possible).

“Sami, I’ve done a lot of drugs. Tried everything, but I’ve never shot anything up my arms. You can try pot if you want to, but let me tell you, I never liked it and I don’t think you will either.” That was the high school “drug talk” I received. The “sex talk” was even shorter. After I told him I had a boyfriend, my dad put condoms in my bathroom drawer and expected me to be wise and use them.

I remember falling asleep to the sounds of his typing. He was and is, always writing. But he works in television, doing camera utility.

He still sings, and is good at it—always the life of the party. People are always laughing, all eyes on him.

We bond by watching Seinfeld. He tries to make me watch TMZ (imagine that!) but I won’t have it.

He’ll be opening the fridge or sitting on the couch and then he’ll say it:

“Sami, whatever you do—”

“Yeah, I know. Never lose my sense of humor.”

It’s kept me sane too.