A multimedia profile of the Rockaways and their residents after the storm.

Sandy in My Shoes

The Aftereffects

Sometimes, when we talk about time, about our lives and everything of which they consist, our discussions are melodramatic or cliche—”you only live once,” or “you don’t know what you’ve got until it’s gone.” Ordinarily, I cringe at such reflections when they’re made, that is, until the moment I’m confronted face-to-face with the seed of truth, a universal little fragment of experience, that makes them so viscerally true. For us New Yorkers, the natural wrath of Hurricane Sandy yielded a very particular togetherness, a sentimentality and nostalgia provoked by this extreme collective experience. It was a linkage that spanned to the residents of New Jersey and other coastal states; the storm marked us directly and by the connections of those we were know in the first, and perhaps second, degree.

A couple months later, and the storm’s aftereffects are pushed to the back pages of the news. Today, there is little visible sign in Manhattan of Sandy’s devastation or the mess it yielded—power has been regenerated below 25th Street, the R line is running into Brooklyn, and ConEdison trucks have long cleared from Union Square. But the storm occurred. It has its own Wikipedia page, complete with 318 footnotes (at date of writing). And even if we were not devastated by its waters, we know it did cause long-term effects—we read about the fatalities, the destruction of property; we saw the photographs and heard the audio clips.

There are communities for which the storm retains its face-to-face confrontational effect. There are communities for which the truth of a moment, the value of each day, holds weight because the moment the storm hit and destroyed shifted something very real about their life and their environment.

When I heard from Brandon the details of this project—this haunting report from Rockaway, Queens; about the storm; this testimony to a community’s collective grief—I knew I wanted to participate. Days for certain residents in this city are tinted a different color, and for those in Rockaway, that tint possesses a universality that we outsiders can barely begin to understand.

Confluence presents Brandon’s multimedia project, consisting of audio, video, and photographic work, in an effort to depict the oral-visual history of the post-Sandy Rockaway. —WERONIKA JANCZUK, EDITOR

Artist’s Statement

Hurricane Sandy stopped this city like no other storm. Unlike many people with whom I later spoke, I didn’t find the first few days after the storm a bother. I didn’t lose power, I had a break from school, and I slept in a warm bed every night. I got my first taste of the aftermath of the storm on the Wednesday after the rain had stopped. Seven subway tunnels under the East River had flooded, and I heard about the eery blackout in downtime Manhattan from stranded friends. The thought of a powerless Greenwich Village attracted me, and I got on my bike to go explore the darkness. I was amazed at how different city blocks that I ride on every day felt in the wake of the storm. I’d never experienced such a palpable stillness to the Village. New York City during the blackout felt like a place that I knew only from a quickly fading dream.

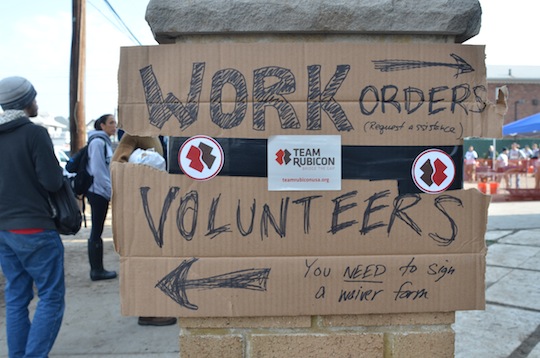

By the time of the weekend I became aware of the destruction in the Rockaways. I emailed an organizer from the Facebook group Rockaway Emergency Alert and was asked to meet at St. Francis de Salles Church at 10 a.m. to receive a volunteer assignment. That first day spent volunteering in the Rockaways marked the turning point for my connection with this storm. While I retained my boyish excitement for the power of nature, I witnessed the storm’s true destruction. People were desperate. Some had lost houses, others had lost family, friends. I spent seven hours that day working in Frances Farrel’s basement, throwing out memories which had been amassing in every filled closet and every poorly sealed plastic drawer for the last fifty years.

As I worked, Patti, Frances’ daughter, directed me. “That’s from when I lived in London,” she said when I grabbed a ruined painting, “My husband was British. My kid’s have dual citizenship.” I nodded and smiled at her. “I’m sorry you have to be the one to hear all my stories,” she continued. I couldn’t help but laugh in my head; she couldn’t have been more wrong about that one. I decided I would record their stories from growing up in this house and having to now sort through the house’s remains.

Everyone I interviewed seemed to recommend someone else with whom I should speak. I started interviewing outside of the Farrel Family, and even spent one day speaking with anyone I would meet in the streets. There was still no power in the Rockaways and most people spent their days sitting outside. I bounced around the neighborhood and started to get a better feel for the community that was hit there. I spoke with Robert and Jeanie, who had grown up next to each other and eventually got married and moved into a house just across the street. I spoke with a teacher at the local school who had lost a sister in the plane crash of November 2001. I spoke with Cleo Lewis Sypher who had spent her one free day after the storm volunteering. My involvement with the relief effort in the Rockaways had become seriously tied up with storytelling. People spoke candidly and genuinely about whatever they felt was important. Some asked me to make requests to politicians, others told me of things they will miss most about their lost house.

As I constructed this oral history, I saw myself as a central character. I edited this project to bring you along on the journey with me, from my original fascination with nature through to my first days volunteering and my time spent speaking with residents.

I got a call from Cleo the other day; she has power and things are mostly back to normal. The smell in her building, however, is worse than ever and it makes her feel faint as she walks out of the door from her sixth-floor apartment every day. The work is not nearly done, even as life seemingly goes on unaffected just a few miles away.—BRANDON KNOPP, DOCUMENTARIAN