“In January 2017, I traveled to Athens and Lesbos to hear the stories and capture the images of people we call refugees.” Photography.

In Their Words

In January 2017, I traveled to Athens and Lesbos to hear the stories and capture the images of people we call refugees. The word “refugee” is just a label; it’s not who they are. They didn’t choose to leave their countries; they had to, because of war or the political situation. Nobody chooses to go through hell unless the alternative is even worse. The people I met were no different from me or my brother or my family. They were some of the strongest, bravest, smartest, kindest, and most generous and inspirational people that I have ever had the pleasure of meeting and talking to and joking with and sharing meals with. They welcomed me into their homes and families. They shared everything when they had nothing to share.

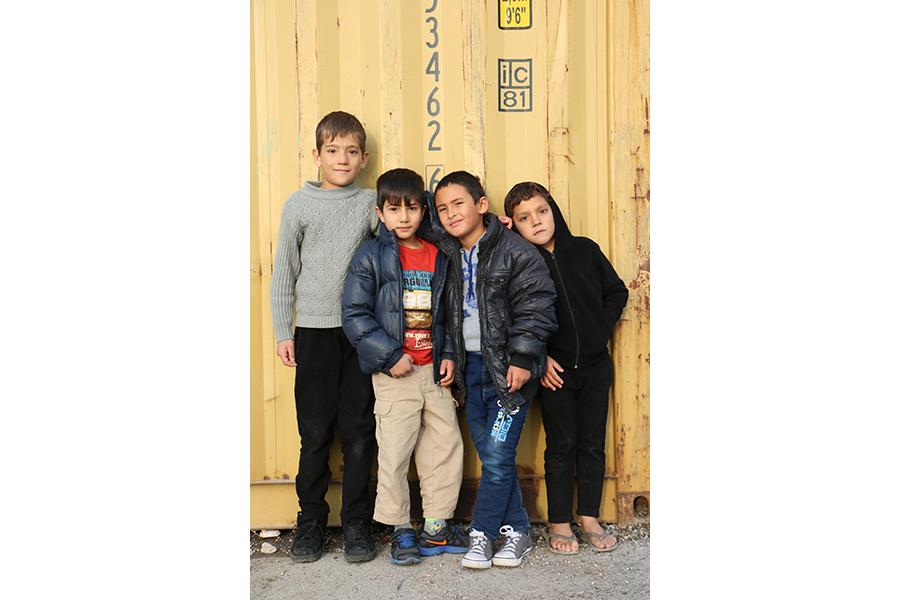

This is my attempt to introduce some of these people to you; to share an aspect of their story so we don’t see them as “foreign” or as a “refugee.” They are mothers and fathers, boys and girls and babies, soccer players, musicians, interior designers, and engineers. I especially loved spending time with the children; they would all want their photos taken, and surround me to see how I captured them in my camera. They would strike cool poses and smile like they didn’t have a care in the world. I was with them on New Year’s day and asked them their wishes for 2017. One said he wanted to be able to go to the shops and buy whatever he wanted, many said they wanted to go to Germany, and some didn’t say anything.

It is their stories that I think we need to hear, especially now.

Artist Saanya Ali sat down with GAF Publicity Manager Carly Valentine to discuss the experience of visiting two refugee camps in Greece. “In Their Words,” which includes interviews, video footage, and sculpture in addition to photographs.

What was the inspiration for “In Their Words”?

I was in Rome for Christmas with my family, and I knew the refugee crisis was happening, but it kind of pissed me off that the media was getting preoccupied with other things and this was still going on. I saw a video that Milana Vayntrub posted, where she went to the camps and said, “This is what I can do, I can tell stories and I have a platform to tell stories.” There is also a film called Refuge that just premiered at SXSW so I had seen a clip of that online. After that, I decided to leave Rome and go to Greece, and I began the trip two days later.

How do you think about the experience now, a few months later?

I came back the day before spring semester started . . . I never have weekends because I’m always working, and I haven’t had a chance to actually think about everything. People ask me “Oh! How was it?” I am kind of at a loss for words so I’m trying to figure it out now as we speak, I guess.

Do you have particular goals for the project?

I’m still in school, so I couldn’t just go and move to the camps and work there; that’s not feasible for me. But I am a photographer and a filmmaker and a storyteller in many different ways, and in that way, I can reignite some attention to the issue because the refugee crisis is just being forgotten and people are just getting bored of hearing about it. My goal is to remind whomever I reach of humanity and the reality of the people behind the statistics. These people aren’t numbers; they have names and families. People’s conception of refugees is that they are poor and need help, but the reality is that these people are lawyers, chemical engineers, and doctors.