A look at memory and representation after World War II, in Alain Resnais’ Night and Fog and W.G. Sebald’s Natural History of Destruction.

Histories in Ruins

Memory and Representation after World War II

Introduction

There is an historical division between collective memory of World War II’s concentration camps and of the Allied bombings of German cities, a discord that began during the war and remains intact today. Responsible for the rift are literary and cinematic representations from the years immediately following the war and into the present. While works about the Holocaust, such as Alain Resnais’ 1955 documentary Night and Fog, endeavor to capture grizzly details of the horrors survivors endured, the few representations of the Allied bombings that do exist commonly do not achieve such pathos. The exception to the latter collection of representations, however, is W.G. Sebald’s 1999 essay Natural History of Destruction (reprinted in an edited form by the New Yorker in 2002). Sebald’s treatment of the World War II bombings runs parallel to Resnais’ regard of the Holocaust; both works examine the ruins of manmade landscapes as a method of uncovering and considering the narratives of these catastrophes. Pleas for historical reflection ground both pieces as they confront the violence exercised against human bodies and physical structures during World War II.

Night and Fog is a film only thirty minutes long that remains among the most acclaimed portrayals of the Holocaust and Nazi concentration camps. Resnais adeptly positions his work as a mediator between the survivors of the camps, non-witnesses, and the past. Through his camerawork and montage, Resnais establishes a necessary distance for analysis from the history he presents while still bringing viewers closer to the reality of destruction in concentration camps than had been done before, and arguably since. Thus, he provides an opportunity for former prisoners to confront their personal histories within the context of a broader narrative, and the film communicates these experiences to those who did not witness the camps themselves. The film also culminates with questions about blame and responsibility. Resnais, with the help of the poet and Mauthausen camp survivor Jean Cayrol, urges viewers to engage continuously in reflection on history and their roles within it.

W.G. Sebald’s writings on the Natural History of Destruction also present a commentary on remembrance, but regarding the Allied bombings of German cities toward the conclusion of the war. Based on his own experiences as a child viewing ruins after the war, first-person accounts of the bombings (mostly written), and novels written after the war, Sebald accomplishes two tasks: examination of how the apathetic attitude of Germans after the bombings contributed to a dearth of testimonies on the events, and a substitutionary depiction of what took place. Through consideration of the response of the German people, Sebald demonstrates the risks inherent to a reliance on witnesses as vehicles for collective memory. His analysis of responsibility also recalls the psyche of Germany at the time of the bombings, whereby many viewed the attacks as inescapable—natural in the evolution of the war. Sebald’s literary reproduction of his understanding of the bombings and their aftermath labors against this narrative to evoke a visceral response of disgust and grief from readers as he confronts them with the consequences of wartime violence. Similar to Resnais’ film, the structure of his writings provokes discourse and contemplation.

Distinctive apathy and visceral grief respectively distinguish contemporary recollections of the bombing of German cities and the operation of Nazi concentration camps. Such persevering emotional responses toward the events of World War II are extensions of perceptions formed in the years after the war, shaped by writings and films meant to speak on behalf of survivors. While the attitude of history toward the concentration camps has been not to forget and to continue to learn, the attitude of Germans toward the bombings has remained one of deliberate ignorance. Fragmented memory characterizes both histories, but while artists have examined the ruins of concentration camps, they have yet to do so with the German cities, and without primary testimony, it may be too late. Thus, some bodies are remembered while others are forgotten, along with the city ruins of which they were a part.

Bodies and Ruins

Resnais begins and concludes his film with shots depicting the ruins of Auschwitz and other Nazi concentration camps. The dilapidated structures and crumbling foundations merge into the natural landscape of the European countryside, creating an almost idyllic setting. These images and the associated music score and narration bookend the film. Between these opening and closing sequences, Renais gives a historical account of the camps’ creation and demonstrates their purpose during the war: to destroy the bodies that the Nazis considered to be waste. Black and white archival photographs and moving footage comprise this section with continued narration by Jean Cayrol. Through his juxtaposition of images of the bodies, both living and dead, and of the remaining ruins, Resnais makes a visual parallel that strengthens the isomorphism between the bodies, absent from the contemporary (1955) images, and the ruined structures that stand in their place. As Marsha Kinder and Beverle Houston write in their analysis of the film, the vividly green grass that blankets the camps also prompts viewers to consider the corpses that have allowed the soil to become so fertile (Raskin 155). The implication of ruined bodies is ever-present.

The effect of isomorphism, whereby images of bodies give way to images of structures, is successful because of the connection people already experience between their own bodies and architectural forms. Svetlana Boym theorizes this connection particularly with regards to decaying ruins as “ruinophilia,” whereby individuals “confront [ruins] and incorporate them into [their] own fleeting present[s].” Boym emphasizes the anxiety that accompanies this isomorphism as people witness the aging and slow decay of their bodies manifested through the ruins of buildings. This phenomenon assists the viewers of Night and Fog in their recollections of images of bodies in the camps when the narrator pronounces during the final moments of the film that “Nine million dead haunt this landscape” (Resnais, Night and Fog). “The ‘missing bodies’ . . . fill the screen” Raskin writes (167). Indeed, as viewers hear these words and look upon the green grass and unidentifiable mangled structures of the camp, they both connect their own forms to the buildings and recall the images with which they were previously presented of similarly unidentifiable mangled corpses. Thus, those bodies become a part of the landscape that viewers see on screen.

Sebald presents an account of the bombing Hamburg in 1943 that also inextricably links the ruins of the city to the ruins of bodies, but he does so in a more conspicuous manner than that employed by Resnais that thoroughly intertwines the ruined forms. He writes:

The fire burned like this for three hours. At its height, the storm lifted gables and roofs from buildings . . . and drove human beings before it like living torches . . . Those who had fled from their air-raid shelters sank, in grotesque contortions, in the thick bubbles thrown up by melting asphalt . . . Residential districts whose street lengths totaled a hundred and twenty miles were utterly destroyed. Horribly disfigured corpses lay everywhere . . . They lay doubled up in pools of their own melted fat, which had sometimes already congealed . . .

Elsewhere, clumps of flesh and bone or whole heaps of bodies had cooked in the water gushing from bursting boilers. Other victims had been so badly charred and reduced to ashes by the heat, which had risen to a thousand degrees or more, that the remains of families consisting of several people could be carried away in a single laundry basket. (Sebald, New Yorker 70-71)

Sebald’s testimony is vivid, poignant, and gruesome. It explicitly links the ruination of Hamburg to that of its people’s bodies, a connection that he perceives the shortage of testimonies from witnesses to the bombings has helped to erase from collective memory. Thus, for Sebald, the consequence of this relationship between the destruction of bodies and cities is that of continued failed remembrance of the ruination of cities’ infrastructures amounts to forgetting of the individuals who perished in this horrific manner.

The ruins of buildings and bodies during and after the bombings were inextricable, yet even those who had witnessed the destruction could not come to understand the scope and significance of the bombings. Sebald relays a diary entry by Friedrich Reck from August 20, 1943 during the exodus of survivors from Hamburg. A large group of refugees attempts to force their way onto a train, and during the struggle a woman’s suitcase “‘falls on the platform, bursts open and spills its contents’” (New Yorker 71). Among the ruined artifacts and trinkets tumbles out “‘the roasted corpse of a child, shrunk like a mummy, which its half-deranged mother ha[d] been carrying about with her, the relic of a past that was still intact a few days ago’” (New Yorker 71). For this mother, her child’s ruined body was almost indistinguishable from her other ruined possessions and the ruins of the city from which she was fleeing. Having heard of other mothers like her, Sebald describes the Hamburg refugees as “distraught . . . vacillating between a hysterical will to survive and leaden apathy” (New Yorker 71). Indeed, hysteria rather than grief seems to characterize the immediate response of witnesses to the bombings, but even that sense of distress did not permeate the psyche of the rest of the country, which had not experienced the attacks.

Ruins and Nature

In addition to a sense of isomorphism between human bodies and structural ruins, Resnais invokes a connection between ruins and the natural landscape with which they merge through their gradual destruction. Resnais’ imagery embodies Walter Benjamin’s arguments regarding the convergence of human history and natural history within ruins, whereby “history does not assume the form of the process of an eternal life so much as that of irresistible decay . . . the events of history shrivel up and become absorbed in the setting” (178-79). Von Moltre furthers this notion through discussion of Simmel’s dialectical theories of ruins, writing that “ruins also ‘collapse temporalities:’ they ask us to contemplate the past within the present, as well as the having-been-present of the past” (401). Resnais begins and ends Night and Fog with images of ruined concentration camps. These sequences emerge as layered temporalities through the addition of narration, contextualization within a natural landscape, and juxtaposition with the archival images from the War. This convergence of time allows viewers to examine history, but the tension between nature and the ruins of the camp also conveys Resnais’ message about remembrance: if the history embodied by the ruins becomes indistinguishable from the natural landscape, that history, and the bodies that perished within it, become forgotten.

With regards to Sebald, the lack of anger among the German people following the bombings was as if they were responding to a natural disaster. Karen Remmler writes that “one can write off violence as part of human nature, just as one can write off ‘natural’ disasters as acts of God” (Remmler 46), and that “Even the most horrific atrocity will at some point be conveyed through metaphors that are associated with other less intentional forms of destruction—including natural disaster” (59). Sebald’s perspective on the German response to the bombings is that they found them “inescapable” (“Zürich Lectures” 14), a natural progression of war, and even a logical response to the actions of the Nazis. Further, Germans did not speak about the events afterward, because “the true state of material and moral ruin in which the country found itself was not to be described” (Sebald, “Zürich Lectures” 10). Under this logic, and employing Remmler’s notion of the “natural disaster,” Germans came to perceive the ruins of their cities as natural landscapes, the rubble dissociated from human deeds. Benjamin writes that “In the ruin history has physically merged into the setting” (177), and its remembrance becomes dependent on the narratives formed by interpreters. In the case of German cities destroyed in World War II, however, few accounts emerged. Thus, the decay following the “natural” events of destruction in Hamburg and other cities became almost mundane, and the history forgotten.

Both Resnais and Sebald also suggest that these instances of destruction occur as parts of natural cycles of history. Resnais emphasizes this natural cycle in the final minutes of archival reels and photographs, when he depicts the Allied liberation of the concentration camps. The narrator dictates that:

When the Allies open the doors,

All the doors,

The deportees look on without understanding.

Are they free?

Will life know them again? (Resnais, Night and Fog)

Between these lines, Resnais illustrates the Ally cleanup of the camp. One clip shows a bulldozer churning rubbery corpses with filth as it pushes them toward a mass grave, the surviving inmates looking on. Ally soldiers carry limp bodies on their backs toward the pits, slinging them unceremoniously to lie among the thousands of others. The liberators lay skulls in neat rows, as if planting them as crops. The liberation of the camps does not become a liberation of individuals or of their human identities. Thus, Raskin writes that:

We see this not as an isolated spectacle of horror, nor the camps themselves as mere sociopathic freaks, but as parts of an organic system, designed, run, and consented to by men —men, for the most part, of the common kind . . . The dark, poisonous bloom of a nightmare grew in a soil of day-to-day routine. (153)

For Resnais, this dark time of human history is none too darker than many other times, nor the perpetrators particularly more evil than other people, past and present. There is natural predictability to cycles of human behavior.

Sebald argues for a similar narrative of human history, articulated through the title of his works: Natural History of Destruction. Sebald borrows this title from Lord Solly Zuckerman, who intended to write a report by the same name based on his visit to Cologne after the bombings. When Sebald later questioned Zuckerman about the unwritten report, the Lord could remember only his desire to include “the image of the blackened cathedral rising from the stony desert around it, and the memory of a severed finger that he had found on a heap of rubble” (New Yorker 73). The image parallels Sebald’s discussion of the ruined cities as natural landscapes, but it is also emblematic of the cycle of human destruction: from the rubble of disaster emerge new bodies who will continue the pattern. Disaster becomes “a process rather than event” (Remmler 47) within the narrative of human history, and “processes” require little intervention apart from the natural forces that guide them. The events of destruction on this scale, Sebald writes, occur at the point at which humans “drop out of what we have thought for so long to be our autonomous history and back into the history of nature” (“Zürich Lectures” 66). The unconscious function of humanity in the natural perpetuation of this destructive cycle is amendable only through the proliferation of documentations that help to cultivate collective memory.

Ruins and Memory

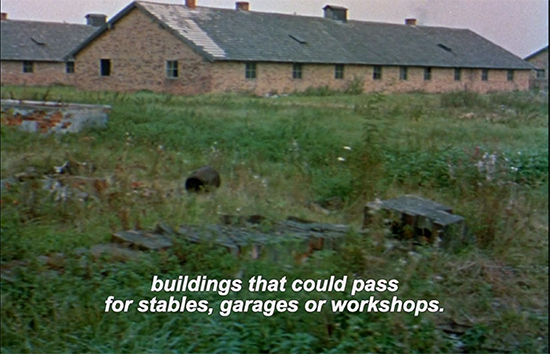

Through Night and Fog, Resnais consolidates collective memory of the Holocaust around the ruins of Nazi concentration camps. His work embodies Helmut Puff’s argument that the precision of documentary representation “serves as an antidote to the lure of forgetting the past altogether” (266). The truthfulness of Resnais’ film originates with the photographs he compiles to portray the generalized experience of the concentration camps. He further resists the “lure of forgetting” by establishing a tension between the sequence of graphic archival images and his “deliberate, passionless examination” of contemporary camp ruins at the beginning, middle, and end of the film (qtd. in Raskin 153). Roger Sandall describes how “These mute relics [thus] seem pathetically neutral . . . seen detached from their incredible history. Imagination recoils, conscience falters, and . . . me forget” (qtd. in Raskin 153). Cayrol’s narration acknowledges its inability to completely represent the histories depicted:

Those wooden blocks . . .

No description, no shot can restore their true dimension:

Endless, uninterrupted fear . . .

Only the husk and shade remain . . .

Buildings that might be stables, garages, workshops,

A piece of land that has become a waste-land,

An Autumn sky indifferent to everything. (Night and Fog)

While recognizing their inability to recreate any experience of the Holocaust, Resnais and Cayrol intervene with narration throughout the film to connect disparate images for viewers. The Narration reinforces the isomorphism triggered by juxtaposed images of lifeless bodies and ruined edifices. Resnais simultaneously draws visual parallels and urges viewers to grapple with the disconnect between the brutal history of the camps and the innocuous ruins that remain to represent that past. The film’s narrative strategy then affirms Beasley-Murray’s assertion that “Ruins . . . have to be spoken for, interpreted, and supplemented” (215) if those who view them are to see beyond their material facades. Without a deliberate generation of narrative for ruins, their histories become easily forgotten.

The title Night and Fog and the final lines of narration of the film also serve as calls for remembrance. The phrase “Night and Fog” is a nod to a decree by Hitler of the same name that required SS officers to arrest civilians in a manner that would make them seem to have vanished into thin air. Hitler appropriated the title from Wagner’s opera “The Rhinegold,” but after the War, the phrase “came to stand for the nightmare suffered by everyone who had been deported by the Nazi’s” (Raskin 22). Resnais’ utilization of this title signals the function of his film to resist the fading of collective memory regarding the destruction of the Holocaust.[1. It is important to note that Hitler’s “Night and Fog” decree was not related to the arrest of individuals for deportation to the concentration camps, but rather to the detainment of civilians for “offenses against the Reich or its armed forces” (Raskin 15). Resnais invokes the sentiment of the decree.] The film’s final lines of narration are Resnais’ ultimate plea for remembrance:

War nods, but has one eye open.

Faithful as ever . . .

Who is on the look-out from this strange watch-tower

To warn us of our new executioners’ arrival . . .

There are those who look at these ruins today

As though the monster were dead and buried beneath them.

Those who take hope again as the image fades

As though there were a cure for the scourge of these camps.

Those who pretend all this happened only once,

At a certain time and in a certain place.

Those who refuse to look around them,

Deaf to the endless cry. (Night and Fog)

The end of the camps’ operation, for Resnais, is not the end of the destruction that the ideology behind them can inspire. The forces of ruination are always available for those who choose to employ them, and general ignorance about the history of destruction increases the likelihood that such forces will resurface. Resnais frames the film “to inspire soul-searching from which no one could exempt himself or herself” (Raskin 9) in order to resist collective oblivion with “an unmistakable implication that every society bears within itself the potential for ruthless oppression” (171). The cultivation of collective memory is a collective responsibility.

Sebald appeals to the same notion of collective responsibility for remembrance through his analysis of the functions of German apathy and psychological shock in national neglect of history. He describes the “individual and collective amnesia” (Sebald, New Yorker 68) of witnesses to the Allied bombings who, as Alexander Kluge records, “‘lost the psychic power of accurate memory, particularly within the confines of the ruined city’” (qtd. in “Zürich Lectures” 24). Sebald thus acknowledges the questionable reliability of memory and primary testimony for chronicling these events, but he also attributes responsibility for the dearth of historical documentation to a collective consciousness oriented “exclusively towards the future” and consenting to “silence about the past” (“Zürich Lectures” 7). Political pressures and the effects of trauma in the immediate aftermath of the war prevented a national examination of Germans’ positions as both culprits and victims of destruction on a “scale without historical precedent” (Sebald, “Zürich Lectures” 4). After the Ally air raids, “The need to know [for Germans] was at odds with a desire to close down the senses” Sebald explains (“Zürich Lectures” 23), and few testimonies ever emerged to resolve that tension. The consequence has been a ruination of collective memory.

Conclusion

Through their respective cinematic and literary works, Resnais and Sebald urge audiences to engage in reflection on near and distant histories. Only through continuous appraisals of the past, they argue, can society preserve collective memory not only of events themselves, but also of the individuals who perished as part of them. Both artists utilize ruins to connect viewers and readers with World War II’s Nazi concentration camps and Allied bombings of German cities, because “ruins invite their visitors to travel along related temporal vectors into the past” (Von Moltre 398). Resnais and Sebald draw parallels between the ruins of buildings and the bodies that became ruined within them. They also highlight tensions between nature and the remains of manmade structures as the two become indistinguishable over time. Their two works demonstrate the need for witnesses of destructive histories to create narratives from ruins to cultivate collective memory. Though this process may not preclude future instances of architectural and bodily destruction, it promotes a bolder examination of connecting histories to resist catastrophic ruinations of memory.

Works Cited

Beasley-Murray, Jon. “Vilcashuamán: Telling Stories in Ruins.” Ruins of Modernity. Ed. Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2010. 212-31. Print.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Trans. John Osborne. London: Verson, 2009. Print.

Boym, Svetlana. “Ruinophilia: Appreciation of Ruins.” 2008. Atlas of Transformation. Ed. Zbynek Baladrán and Vik Havránek. N.p.: JRP|Ringier, 2011. N. pag. Atlas of Transformation. Web. 23 Apr. 2016. <http://monumenttotransformation.org/atlas-of-transformation/html/r/ruinophilia/ruinophilia-appreciation-of-ruins-svetlana-boym.html>.

Dir. Alain Resnais. Night and Fog. Screenplay by Jean Cayrol. Narr. Michel Bouquet. Composed by Hanns Eisler. Argos Films, 1955. Hulu. Web. 23 Apr. 2016.

Dir. Alain Resnais. Night and Fog. Screenplay by Jean Cayrol. Narr. Michel Bouquet. Tran. Alexander Allan. Composed by Hanns Eisler. Argos Films, 1955. Berkley Library University of California. Web. Transcript. 12 May 2016.

Puff, Helmut. “Ruins as Models: Displaying Destruction in Postwar Germany.” Ruins of Modernity. Ed. Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2010. 253-69. Print.

Raskin, Richard, comp. Nuit et Brouillard by Alain Resnais. Aarhus C: Aarhus UP, 1987. Print.

Remmler, Karen. “‘On the Natural History of Destruction’ and Cultural Memory: W.G. Sebald.” German Politics & Society 2005: 42. JSTOR Journals. Web. 19 Apr. 2016.

Rentschler, Eric. “The Place of Rubble in the Trümmerfilm.” Ruins of Modernity. Ed. Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2010. 418-38. Print.

Sebald, W. G. “Air War and Literature: Zürich Lectures.” Trans. Anthea Bell. 1999. On the Natural History of Destruction. By Sebald. Trans. Anthea Bell. New York: Random House, 2003. 3-104. Print.

– – -. “A Natural History of Destruction.” New Yorker 4 Nov. 2002: 66-77. PDF file.

Von Moltre, Johannes. “Ruin Cinema.” Ruins of Modernity. Ed. Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle. Durham and London: Duke UP, 2010. 395-417. Print.