“But how do the derivatives of the accidental, representative ‘poor image’ function?” An analysis of Rebecca Black.

Persona in the Cultural Realm

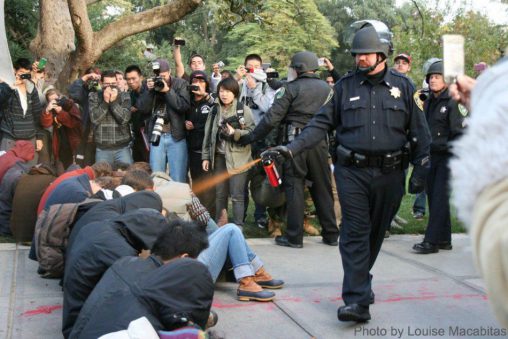

A popular meme that stemmed from the Occupy Wall Street movement calls attention directly to an individual: Lt. John Pike. The original Casually Pepper Spray Everything Cop image shows the police lieutenant strolling nonchalantly, his face void of emotion, with one arm outstretched to pepper spray a group of nonviolent Occupy protesters at the University of California Davis. The Washington Post notes Pike’s appearance “in some of the world’s most famous paintings as part of an Internet meme intended to shame him for his actions.”1 He casually sprays God, Liberty, himself, the figure in The Scream, children praying to Jesus, and cute cats. In the eyes of the content creators, he deserves to be publicized; there is a story worth telling, and juxtaposition against the good, innocent, suffering, and nonsensical suggests that his action was inhumane.

But how does a meme function when the remixed image is less tangible? Reducing a person to a persona—naught but a signifying actor—swaps personal character with pure significance. Consider Rebecca Black and her infamous “Friday”: She embodies all of the criticism associated with the piece as the single representative “image” of a poor music video. Her fame has nothing to do with personality flaws or ethical stance but rather a failed earnest attempt. In this way she is morally superior to Pepper Spray Cop: her error stems from not from a poor decision but rather submission to the requirements of fame, following the clichés of the music industry to the letter, perhaps further than any popular figure has done. Her too-familiar image screams so loud of its intent that it refuses dismissal even in failure; the perfectly poor persona demands individual response. So what happens to Black’s persona as she circulates the cultural realm?

The opening sequence of “Friday” establishes its artificial nature. The title appears between its creators, Rebecca Black and Ark Music Factory (0:00-0:03), immediately followed by an automatically computer-rotoscoped image of the teen singer trapped behind words on the page: “SUNDAY” and “Study Study Study Study” (0:03-0:05). Of course a “music factory” would churn out the cliché subject of a young student’s anticipation of the weekend, and her hastily rotoscoped image further enforces that this piece could be considered lazy art. Meanwhile three synthesizers construct a pulsating sound image, encouraged in the right ear by a male vocalist uttering “yeah, a-a-a-a-a-ark,” in the left by a matching digital scratch, and in the center by Rebecca’s own “oooo yeah.” Such self-assuring music, especially along with the sharp 1080p video, expresses that its creators take it seriously and intend the listener to do so as well. And since the producer digitized the vocals, with strong pitch correction on the female and distortion on the male, the intro is void of any organic sound; every element, since synthetic, must have been constructed with purpose, so suddenly the lazy art becomes inherently “bad.” Finally a digitally synthesized human whistle occurs across film cuts to transition to a slide titled “WEDNESDAY: Music Practice” (0:07-0:08). This whistle, easily lost in the busy intro, fills the audial void between Black’s “yeah-yeahs” to retain audience interest. That stimulating frequency range, heard in the whistle and Black’s Auto-Tuned voice, grips the listener throughout the intro’s seventeen seconds without verse just as Black’s chores carry her through the week. And when the viewer interprets the piece as “bad” art, the whistle mocks the song by directing the viewer’s attention to the digital image of Black singing without emotion behind the prospect of “music practice;” music is just one of her weekday chores that facilitate the promised enjoyment of the weekend. So why should she deserve her fame?

Since Ark Music Factory earnestly offers its “young talent” the “tools to become a pop star,” its production work emulates the fabrication of contemporary music celebrities. Thus “Friday” unintentionally satires the lack of meaning and organic sound found in pop music, functioning as an exemplary poor image of the industry’s ideals. The popular music industry traditionally uses some form of representation for the sake of promotion, whether it be a persona such as Britney Spears, a concept like Radiohead’s “In Rainbows” pay-what-you-like release, or a branding device like Daft Punk’s futuristic helmets. Considering a broadly applicable definition for art as that which affects the viewer, such presentations become the art just as much as the music itself if not more so. Since any self-cognizant satire of the industry lacks an independent presentation form, instead exaggerating the image of the satirized directly, it must exist outside of the music industry. The familiarity of intentional satire prompts the listener to effortlessly categorize direct satire as such and consider it a secondary derivative art. But a hyper-serious attempt, an extreme example of popular ideals, can function within the popular music system reliant on representation because it represents itself. “Friday” distinguishes itself as an accidental parody: a collection of the “bad” one finds in music industry—overuse of pitch correction, lack of significant lyrical meaning, and banal song structure (particularly the common I-vi-IV-V chord progression)—presented as though they were great together under a single image: Rebecca Black. Only such an accidental parody forms the image necessary to ridicule an industry reliant on presentation.

But how do the derivatives of the accidental, representative ‘poor image’ function? A widespread animated gif titled “50 Cent and Rebecca Black Friday” displays 50 Cent laughing and driving off in response to Black asking “which seat can I take?” The image quality, like a YouTube video of the same conjoined scenes, suffers greatly from compression and reduction of resolution. But in both cases the message remains clear: Black is a spectacle to be laughed at. Her self-presented, publicly-interpreted image is so poor that it transcends the limitations of a technically poor combination; if she, the extreme reflection of pop music ideals, asks for a ride, the driver ought to laugh in her face and speed off. The lacking image quality here distorts the depiction of reality, setting off both scenes just enough to allow the viewer to suppose that they have commonality enough to exist alongside one another. Had both 50 Cent and Rebecca Black appeared in the highest available definition, the technical differences would distract from the supposed reality where the two images exist together. In this way the degraded image enables a content creator to further exaggerate the perfectly poor image of Rebecca Black’s persona; she is the poor image whose purpose is to further promote the video’s “success,” and as such her visual degradation is essential for her derision.

Kohl’s Black Friday advertisement released November 17, 2011 seems to parody Black’s song. The recording and image quality is relatively pristine, save an audio rendering error that caused the audio image to pan unnaturally to the left. This mishap aligns well with a similar oversight in scripting and audio production. Its calculated lyrics “gotta go to Kohl’s on Black Friday / Everybody’s going there at midnight” and the natural, more pleasing vocal tone eliminate the very essence of the original: in what way does this advertisement parody anything beyond recycling the familiar tune? Either the advertising team doesn’t get it, or they simply don’t care. It is not an attempt at parody at all, but rather simply an abuse of melody recognition. Black’s image, although referenced, does not appear here. Rebecca Black is insignificant to Kohl’s beyond a viral melody and a bit of Internet buzz.

Since the popular interpretation of “Friday” differs from Black’s intention, one could consider her subsequent appearances as derivatives since their relevance comes as a direct result; she responds to herself. These works have a distinct purpose: to preserve her fame. She attempts to position herself as a more permanent celebrity when she announces in an interview on Good Morning America that a duet with Justin Bieber would “make her life.”2 Doing so would function just like Kanye West tweeting Bon Iver to fame or Usher’s symbolic adoption of young Bieber: a celebrity publicly recognizing someone as fame-worthy, exactly the support Black needs to perpetuate her relevance.

The original “Friday” video itself even includes a trace of this desire for a celebrity recommendation. After the bridge of the song, an out-of-place character appears. Co-producer Patrice Wilson, both the only adult and the only African American in the video, delivers several rap lines seemingly irrelevant to Black’s weekend plans. It’s difficult to ignore the similarities between his hair style and that of Usher: very short, with nearly identical shaping above the forehead and a beard length just pushing beyond stubble. Justin Bieber fans know that Usher “discovered” him, so including in “Friday” an older figure who can drive, wears diamond earrings and a nice watch, and creates the nickname “R. B. Rebecca Black” (2:30) attempts to enforce her apparent fame in the same way that it worked for Bieber.

Finally Katy Perry, a “real” celebrity, asks Black to appear in her video “Last Friday Night (T.G.I.F.),” her apparent ticket to long-term success. In the video Black hosts the perfect party and gives Perry’s nerdy character, Kathy Beth Terry, a makeover to attract the college jock, making her ignore her fellow-nerd love interest. While the makeover does attract the jock, that he later tries to take advantage of her while she is drunk criticizes the superficial ideals Black embodies. Instead, Kathy’s medieval “loser” love interest reigns by battling off the superficial jock, suggesting that her more natural, nerdy self deserves protection. Perry’s created character, Kathy, acts as a foil to Black; she is the self-cognizant “loser” teen while Black is the life of the party, so when Kathy discovers she is a genuine party animal, Black could just as easily turn out to truly be a “loser.”

In casting her video Perry abuses Black’s perfectly poor image for the viewer’s instant understanding of pretentious superficiality under the guise of being “cool.” Although Black gains some social clout from her appearance, by no stretch should this satisfy her dream of singing duet alongside a celebrity. Her role in this clip is clearly subordinate to Perry; in no way does the video imply that Black’s image in the video “Friday” has value beyond a superficial celebration, so her fame is stifled. “Last Friday Night” defines her celebrity role as stagnant, nothing more than a symbol to reference.

Black is an aging accidental star, desperate to maintain her status on a platform that would much rather criticize her work than ignore it, let alone directly enjoy her art. The top-voted comment on a related video with nearly 1.5 million views, titled “Rebecca Black – Friday (Official Video) PARODY,” declares “friday doesnt need a parody. it IS a parody.”3 “Rebecca Black” does not represent Rebecca Black at all; she is merely the product of a generation raised to seek fame, one whose popular music holds certain ideals above others. What she and Ark Music Factory created did not attempt to satisfy their own artistic desires, but rather those of the music industry. And the music industry holds standards that attempt to appeal to the greatest number of people. So her poor image, the persona created in “Rebecca Black,” is the byproduct of a recursive process looping what the masses demand of the music industry through what an average person understands to comprise popular music. Rebecca Black emulates an emulation of her audience, and the result deeply resounds with them in a likely unintended way. Her persona in “Friday” is a familiar compilation of what individuals are assumed to want of popular music. You are Rebecca Black.

- Maura Judkis, “Pepper-Spray Cop Works His Way Through Art History,” The Washington Post Style Blog, November 11, 2011, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/arts-post/post/pepper-spray-cop-works-his-way-through-art-history/2011/11/21/gIQA4XBmhN_blog.html

- “Worst Song Ever? Rebecca Black Responds: ‘I Don’t Think I’m the Worst.’” YouTube Video, 05:38, from a segment televised on ABC on March 18, 2011, posted by “ABCNews,” March 18, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AjFIzWjT5I4.

- LoveyDovey425, comment on “Rebecca Black—Friday (Official Video PARODY,” YouTube video),” YouTube Video, 3:15, posted by “Bart Baker,” March 19, 2011, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nVlY3ZTrBkw&lc=xKquqNbS6rT1HNdYc6KBeoLKtMlvNy1piXf6GfpgV_Y.