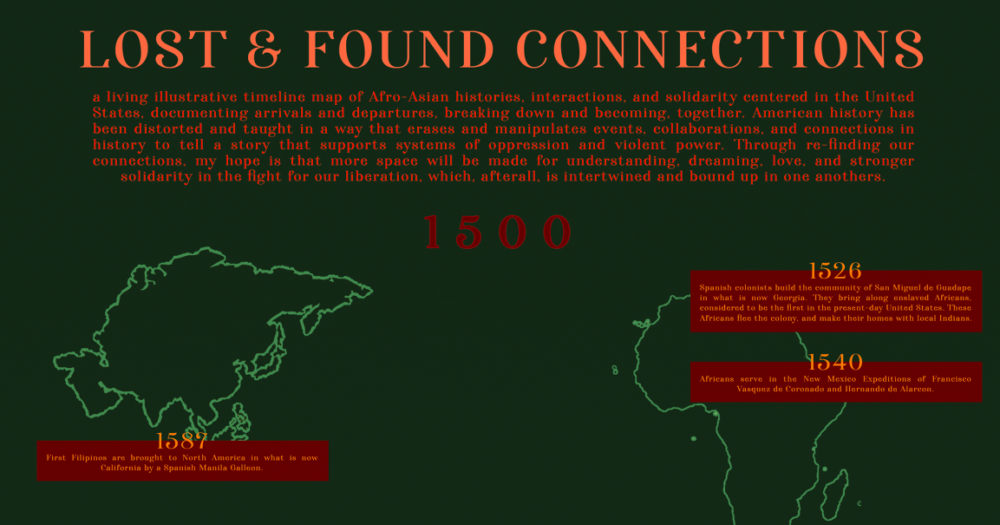

An illustrative timeline of Afro-Asian relations in the United States spanning more than 500 years

Healing Is Not Linear

In this timeline map, I want to think of history, progress, and journey not as a rigid timeframe after timeframe, but as something that spirals, that loops, that moves and turns and intersects. I want to use art and illustration, and tailored down writing as way to counter visually or physically inaccessible academic documents. As Tsige Tafesse said in her interview with The Outline, “the reason why we center art so often is that there’s, to me, a lot of radical potential there because it’s not valued by larger systems of oppression.”1 It’s playing outside the rules of traditional structure and academia; it’s what Christina Sharpe calls it in The Wake—an un-disciplining of the mind. Through nontraditional forms of documentation, documenting arrivals and departures like Gary Okihiro in Family Album History, of documenting similarities and congruencies, of bringing in parallel events typically rendered as separate timelines.

There is a tension in bringing beauty or simplicity to such weighty topics, the danger of not doing our ancestors justice, the danger of essentialisms or beautifying pain. Something I thought about continuously through the construction of this project is how to make information neutral but honest, beautiful but true. Though this timeline is meant to map Afro-Asian relations in the United States, I as an artist am not free of my own positionality, and my own Asian-American story that shapes how I see the world. I am an artist-creative-scholar-dreamer-Asian-American-etc-etc-etc-human who believes that personal investment in what I am writing or designing does not disqualify my work from being truthful and honest. This project is special to me because it is an uncomfortable stretching practice of putting the personal into the public through work that doesn’t necessarily fit within traditional academic work. It is a practice of creating only for myself and for my community’s growth, and not worrying about rendering myself or my community’s trauma readable or easily digestible by Western eyes, while making sure that it is visible and available.

In Michel Foucault’s Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias he frames the tension between true home and belonging (utopia) and what one can hope to construct on earth (heterotopia).2 In our activism and self-discovery, dreams for utopia ground our building of heterotopias. Creating spaces that feel like home and finding belonging is a form of rebellion against violent displacement, a rift in the intersection of time and space as it is to break out and create warmth and comfort in a structure that allows no space. It is in these alternative spaces, finding home in margins as well as breaking out of the margins to construct homes and take up space in the center, that power is held.

As Gloria Anzaldúa writes in her open letter, “I write to record what others erase when I speak, to rewrite the stories others have miswritten about me, about you. To become more intimate with myself and you. To discover myself, to preserve myself, to make myself, to achieve self-autonomy.”3 In revealing what has been erased or separated, in not rewriting history but bringing undercurrents to the surface, we can move toward mutual understanding and greater healing and solidarity. In this mapping timeline, I wanted to rewrite and re-illustrate the history that was miswritten about Afro-Asian relations in the United States. In our class, when asked to write a phrase that I thought of when presented the word “Afro-Asia,” my mind always goes to “lost connections.”This timeline is fueled by the heartbreak I feel when I think about the tension between African-American and Asian-American communities that is the result of the oppressive majority’s construction of insidious ideologies over generations such as stereotypes about African-Americans, the erasure of stories of solidarity, and the model minority myth. In my project, I want to record what has been erased from my story and my learning of how my community engages with other communities. As Yusef Omowale says in “We Already Are” on Medium, “We are not marginal or other to the archive, but integral to it. We may be silenced or made invisible, but we have always been present.”4

Through making this timeline I am reminded that it is not an act of great accomplishment or glory or discovery, but the revealing of stories that have always, always been present, and are integral to the formation of the commonly told story of who we are.

Creating this timeline in Professor Diane Wong’s Interdisciplinary Seminar “Black Power, Yellow Peril: Toward a Politics of Afro-Asian Solidarity” has been an opportunity to discover Afro-Asian solidarity and relations, to preserve them, and to make new my understanding of myself and the world through it. I hope to be able to share it with others to be interpreted in their own light and so that we as a community can heal closely, more intimately, and with more understanding and grace for ourselves and for others. As Lama Owens says in Radical Dharma, trauma can be healed through the cultivation of awareness practice — learning to identify, accept, investigate, and learn to let them go with sustaining heart practices.5 The interdisciplinary seminar has been a cultivation of awareness that I want to manifest in this mapping timeline. Timelines and maps should be an open space of growing, ever expanding archive, of multiple narratives coming together to tell the complex story that is our becoming.

More than anything, this project to me is about love. And healing justice, through love, for our communities that have had this stolen, plundered, erased, from them for so long. I imagine justice without violence to look a lot like rising beyond the idea that resistance and struggling against oppressive structures and systems is the only way. Healing justice looks like rising above the struggle, subverting it with powerful love, hope, and dreams, of freeing our minds to free our bodies. It looks like acknowledging that like our stories in this timeline, our liberations are bound up in each other’s. Healing is movement and work towards wholeness, not a definite endpoint but a work in process. Healing is a result of forgiveness, but does not always mean forgiveness. It is embracing discomfort and reworking our relationships with experience (Owens 65-68). It opens heart space for understanding others and for sharing mourning and acknowledging burdens, and for collective healing. I want my work to be one that overflows in love but also challenges viewers to step into the discomfort of acknowledging and learning about past, to step into talking about the elephant that has been trampling the room for so long. My dream for our communities is such radical love and healing that it shakes foundations and old structures of colonialism and patriarchy, love so powerful and so public and so free that it makes people afraid.

Okihiro says in Family Album History, “Family albums help to define a personal identity and locate its place within the social order and to connect that person to others, from one generation to the next, like the exchanging of snapshots among family and friends. Gary Y. Okihiro, “Family Album History,” Margins and Mainstreams: Asians in American History and Culture (University of Washington Press, 2014), 94.[/fn] My hope with this mapping timeline is to be just one of many family albums of our Afro-Asian community family. To connect one generation to the next, one community leader to another, one family to two families to a thousand, to connect two hearts together. This mapping timeline is a celebration of histories, memories, joys, traumas, that are seen, held, grappled with, spoken through and over and into, and loved. It is a surrender to the vulnerability of being in community, to stories being unearthed to be healed, to hearts open, to the weight and stretching of expansive, encompassing love.

Download “Lost and Found Connections,” a timeline map of Afro-Asian histories, interactions, and solidarity, centered in the United States, across more than 500 years, or read a text only version (PDF).

- Ann-Derrick Gaillot, Ann-Derrick, “Why Art Collectives Are Gaining Ground,” The Outline, July 19 2017.

- Foucault, Michel. “Of Other Spaces: Utopias and Heterotopias.” Facing Value: Radical Perspectives from the Arts, by Maaike Lauwaert et al., Valiz, 2017, pp. 164–171.

- Gloria Anzaldúa, “Speaking in Tongues: A Letter to Third World Women Writers,” This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color, by Moraga Cherríe and Anzaldúa Gloria (SUNY Press, 2015), 169.

- Yusef Omowale, “We Already Are,” Medium, September 3, 2018.

- Lama Rod Owens, “Remembering Love: An Informal Contemplation on Healing,” Radical Dharma (North Atlantic Books, 2016), 61.