As racist statues topple, what will replace them? The students of Professor Patricia Kim’s Spring 2020 Interdisciplinary Seminar, “Women and Public Art” imagined the next generation of monuments for their final projects.

Monument Proposals for New York

Introduction by Patricia Eunji Kim

Statues aren’t only about “remembering history”—they symbolize who has political power in the present. In New York City, only about 10 percent of the statues to historic figures represent women while very few monuments commemorate BIPOC women, womxn, femmes, and trans women. Although activists, artists, and curators have been confronting such monumental inequities questions for over a decade, the Covid-19 pandemic and Black Lives Matter uprising for justice have brought more urgency to such issues around public art and space. Communities across the world demand new systems of power and justice by tearing down racist and colonial statues.

As these statues topple, what will replace them? The students of Dr. Patricia Kim’s Spring 2020 Interdisciplinary Seminar, “Women and Public Art,” imagined new monuments for their final projects. Students created speculative monument proposals to think about the ways that the pre-modern world and its study matter today. Throughout the semester, students learned how women were made present and absent in public spaces throughout the ancient world, and how monuments reflected different ideas about gender’s relationship with power. Moreover, physical and virtual field trips revealed that ideas about the Greco-Roman past continue to inform our modern monumental landscapes, from our offices of government to the subversive sculptural works of contemporary artists like Wangechi Mutu and Kehinde Wiley. Through these proposals, students consider the diversity of the ancient world while contributing to conversations around equity and inclusion in the academy, history, and public space. Ultimately, this project demonstrates how creative action allows us to imagine new futures and public spaces.

To explore the Monument Proposals and more essays on public art and space in the premodern Mediterranean world and modern-day New York City, head over to our class website, Women and Public Art.

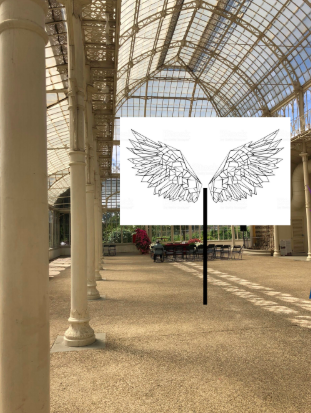

“Wings of History” by Ashley Goetz

What would history look like if it wasn’t written by the victors? Would women’s achievements be put first? How can we imagine forgotten histories informing a modern world?

My monument aims to cast light upon the idea that history is actively remembered, warped, and curated to influence our perception of our reality today. I want to honor women’s stories in the ancient world, and throughout modern history in a feminist specialty: specifically, acknowledging what we would constitute ‘marginalized’ identities in today’s world.

The monument will be set up in Bronx Park, next to the Bronx Zoo.The building will serve as part of the monument, and be ample, dome-like space. Inside of the building, a pair of giant stone wings, with each feather being carved out with a symbol on it, will make a centerpiece.

Each feather will be a monument to a lost story, a forgotten woman, a story rediscovered. When a visitor engages with the monument, they will be able to take an individual feather and place it upon a projector. This unique feather will be carved with a symbol to honor a particular woman/or a group of women throughout history. The projector will play a three to five-minute engagement with their life. I imagine the public engaging with the monument by nominating uncovered stories of women throughout history, and adding recent additions to the piece over time. By participating with the monument as if it is alive, we join the discourse of history.

“Triangle Shirtwaist Workers Monument” by Callie Williams

When I think of forgotten women in New York City, the first thing that comes to mind is the women and girls who worked at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory. The story of these women stuck in my memory after reading a brief subsection about them in my high school history textbook. Every time I walk by the Brown Building on Washington Place, I look up to the eighth and ninth floors, ponder the cobbled street and the women who died on the same stones below my feet, and feel bitter disappointment at the fact that most people walking past me have no idea the events that happened here.

I did not want my monument to be directly interacting with the building, feeling that the structure and the tragic fire that took place there are then what becomes the focal point of the monument, subsequently omitting the significance of these women’s lives both before and after the fire. I decided to make an arch that would be located at the east side of the park’s entryway, aligning with Washington Place where the Brown Building is located just a block down the street. This arch would not rival the Washington Square Arch necessarily, but it would have a juxtaposing effect. Despite the varied use of the land, protests, speeches, and so forth that have happened there, the only monuments in place are the Washington Square Arch, a bust of steel engineer Alexander Lyman Holley, and a statue of the nineteenth century Italian General Giuseppe Garibaldi. This would finally introduce the first piece of public art relevant to the community’s history in the park.

“For Those Killed in the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire of 1911” by Amanda Burkett

The story of the 146 garment workers who perished in a fire, on a site that is now an NYU building, is a known tragedy of the industrial era. Garment workers worked tirelessly for twelve hours per day, five days a week, and seven hours on Saturday, for the modern equivalent of four dollars an hour.

The monument aims to represent what life as a women in 1911 looked like. Based on a contemporaneous photograph of students joyfully gathered, the monument will invite modern students to learn about the duality of women’s history surrounding their campus in 1911.

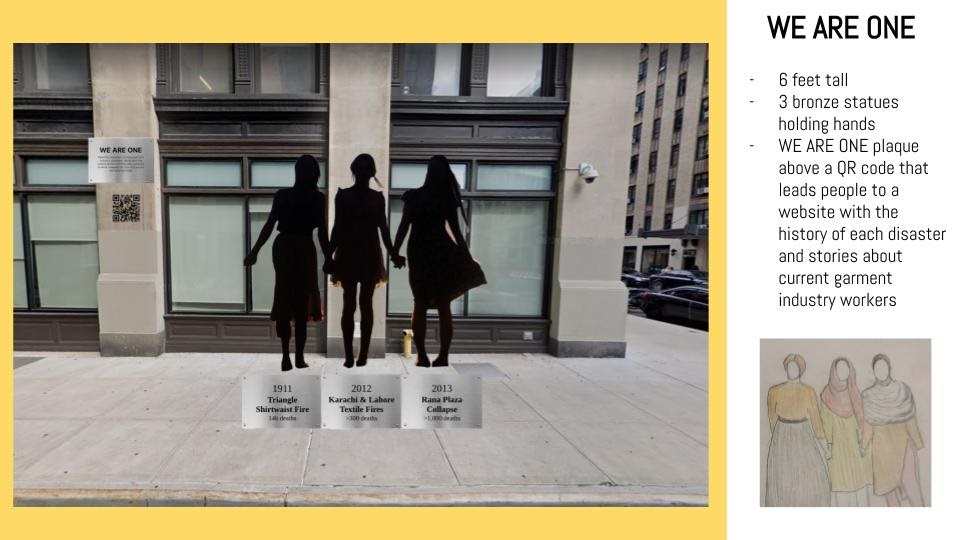

“We Are One” by Olivia Mariscal

Monuments and public art represent history, memories, heroes, and the remembrance of atrocities. In New York City, of the 150 historical monuments, only five of them represent women. What does it mean when there is so little representation of women who have made history and who deserve to be memorialized?

For my monument, I want to honor the many women who worked and continue to work in the garment industry today in New York City, but also in Bangladesh and Pakistan where the garment industry is most prominent today. I was inspired by the tragic history of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory.

Today factory work has moved to Asia where labor is cheaper and where the people can be further exploited by European and American brands. With that said, I also want to honor those who died in the other two largest garment industry disasters, along with those who continue to work in the industry today. In Karachi and Lahore, Pakistan, two fires broke out on the same day in 2012, killing more than 300 workers. Their exit doors were locked and the windows were covered with iron bars making it impossible for the workers to get out of the building and escape. In 2013, outside of Dhaka, Bangladesh, an eight story building collapsed, killing more than 1,000 people. This disaster is considered the deadliest in the history of the garment industry. More than half of those dead and injured were women and young girls. What these all have in common is the large majority of female workers and that they could have been preventable; factory owners knew that the conditions of the buildings were less than ideal and did nothing to fix it.

Taking inspiration from the Comfort Women Column of Strength in San Francisco that shows girls from China, Korea, and the Philippines, I have decided to also use three girls for my monument. I would like to put these human sized bronze statues across the Brown Building on Greene Street. They would be young girls to represent the 80 percent of women that work in the garment industry, and the large number that are underage. I would like to have three girls that come from different nationalities: Jewish-American, Pakistani, and Bangladeshi, representing the three largest garment industry disasters. The girls will also be staring at the building as a way to make people who walk by look up. There will also be a QR code, above a plaque that says “We Are One,” which takes you to a website explaining the history of each of these fires and gives you insight on who is making your clothes today.

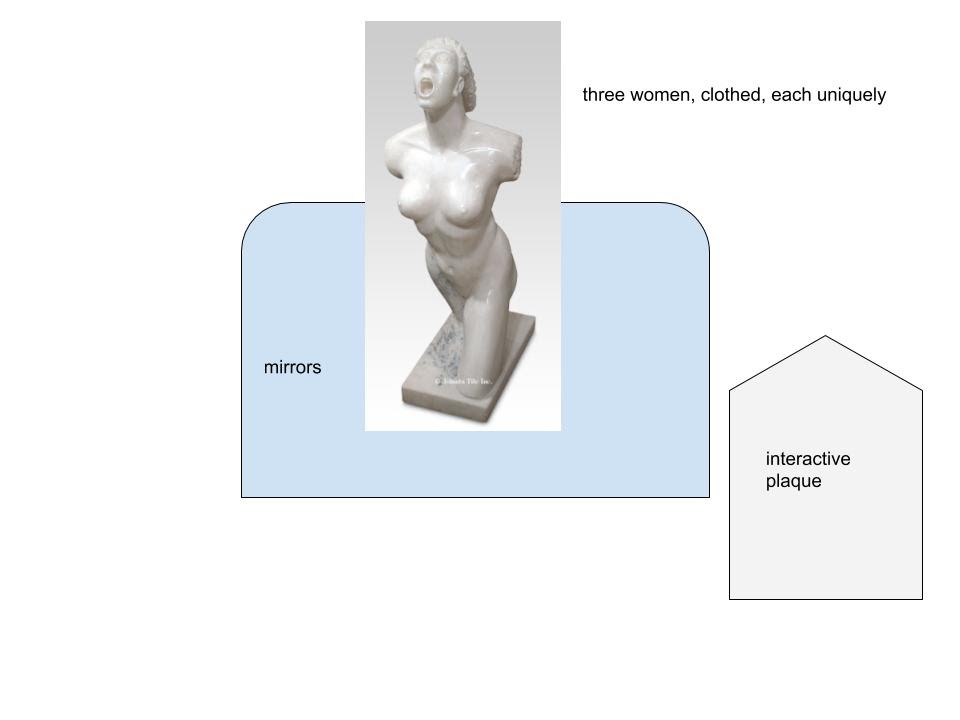

“Queer Voices” by Michelle Loree

We can’t remember everyone all at once, so where do we begin? A place to start is within ourselves, what part of our identity do we wish we knew more about? Is it your race? Culture? Disability? Gender? For me, it was queerness. I identify as a bisexual woman, and I wanted to explore the root of the Gay Rights Movement and find within it the figures that are usually hidden in the background. The non-white, non-male, non-cisgendered members of the queer community who have paved the way for me to be able to hold my girlfriend’s hand in New York City with no fear or reservations.

The Women’s House of Detention was a 1960s art-deco prison lauded as a “luxury experience” equipped with windows in each cell and an open layout for prisoners to interact. This facade hid dark stories of abuse, racial discrimination, and mistreatment that eventually led to the prison being closed after activist Angela Davis took up a mission to expose the prison in the 1970s. The detention center was a block away from the Stonewall Inn, and housed almost all queer women that were arrested in New York City. As a disclaimer, I would like to note that although this was a women’s detention center, we can’t be sure that all of these people identified as women, and many of them were butch, androgynous, and may have had their own gender identifying terms, although transgender was not yet a universal concept or term.

During the Stonewall uprisings, the imprisoned women fueled the protesters below with energy and strength. The women screamed from their windows, cheering the marchers on and throwing flaming toilet paper from above. Almost every lesbian on the ground arrested at Stonewall was taken to the Women’s House of Detention. Shouting from their windows they were the “nerve center of the rebellion.”

I want to honor these women whose voices were muted and stories were forgotten, and who so badly tried to have their stories heard. In Christopher Park, there is a Gay Liberation monument to commemorate Stonewall across from the Inn. The monument is four people, all white, in normal clothes, two women and two men. The women are in a pair, as are the men. To me, the monument is binary and vague and doesn’t represent the diverse group of queer people who combined to create the Stonewall uprising.

My monument would be in the same park, which could be seen from both the Stonewall Inn and the detention center if it still stood. My monument would pull upon references from antiquity in its marble material and acknowledge a history of sex workers and female oppression. The floor of the monument would be mirrors, and then there would be three marble statues of women. The women would be dressed diversely, without gender-conforming clothing, and all screaming, just like the women in the prison. The mirrors serve to allow onlookers to see themselves among the women, to relate to them, and to be part of the movement.

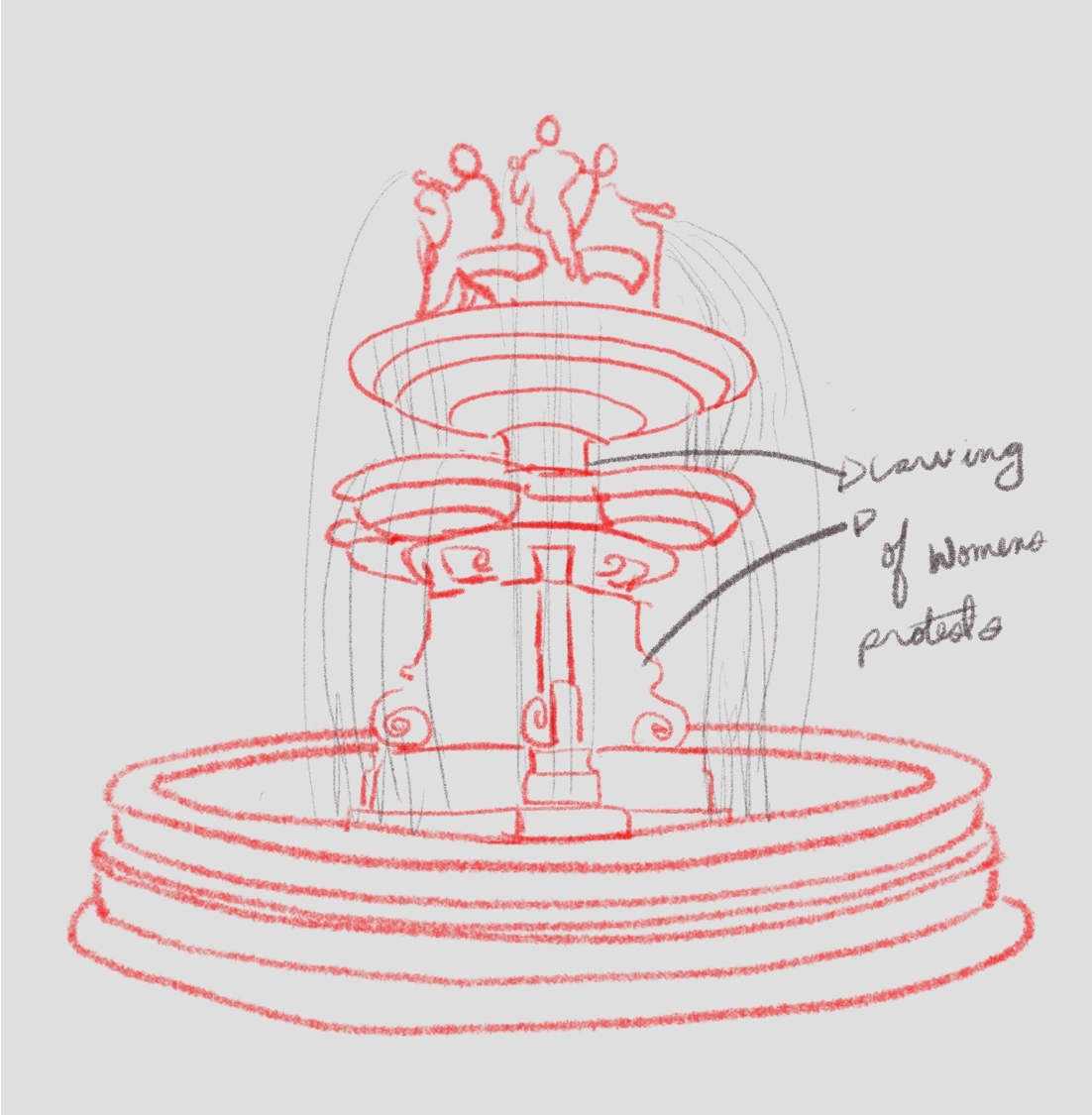

“Women’s Liberation Fountain” by Jasmine Buckley

The monument I’m proposing is inspired by the Women’s Liberation Movement. Its purpose is to memorialize the women within the movement’s diversity in race, class, and sexuality. The monument will be a twelve-foot tall, three-tier marble fountain. At the top of the fountain are five bronze women standing back to back in a circular formation holding shallow bowls with fountain hoses installed in the base of the bowl. The water will fall from these bowls into the second tier of half singular pools, which also have fountain hoses, below each woman figure catching that water. These pools will sit above a rectangular platform base plated with bronze engraved with protest designs of women. The final pool tier will have lights installed in order to capture attention during the nighttime. The edges of the final pool tier will be wide enough to sit on.

The purpose of this monument is remembering women of the liberation movement who have been forgotten by history. Their struggles and the injustices of a country that mistreated them and saw them as expendable are being buried. They, as women who struggled deserve to be carried and be present today. It’s also telling women in general within these communities today that there is a need to fight, there is a need to maintain their identity and make themselves known so that the injustices of women of color do not once again become buried.

I would want to set up my monument on the West side of Central Park below 72nd Street. My reasoning for the position of the monument here, although possibly difficult to achieve, is that it will be adjacent to the Women’s March Route. The Women’s March, and today’s Feminist movement, has been met with a similar whitewashing. Women of color and the issues that affect them, have been less represented in the movement, similar to what was occurring in the Women’s Liberation Movement. Because history is slowly starting to repeat itself, I think it’s important for there to be a physical reminder to remember all women within the movement, so it is impossible for history to erase them again.

“Frescos in the Heights” by Shaina Vallejos

A lot of times when New York City gets discussed, represented within popular culture, to the world, or within academia it is often (re)presented through a lens of beauty. We often see beautiful skylines, aesthetically pleasing buildings, the lights of Times Square, and the filled streets of downtown Manhattan. In reality, these representations of New York City are one-sided because the important parts of New York city, the parts that are real, raw, and integral parts of the city are left out or they aren’t even considered.

When I thought about creating a monument for New York City, East Harlem, Washington Heights and Inwood were my main focus. I decided on Washington Heights for my monument proposal because I’ve been in and out of the heights since a very young age. I also have a lot of family friends that live there and I used to live there myself.

For my monument proposal I chose to integrate Frescos onto the ceiling of the 168th one train station in the Heights. The 168th street station is almost 100 years old. Last year, the MTA began construction on this station and it was supposed to be done this January, but part of it is still under construction. The Heights’ 168th street subway station is just one of many uptown stations that gets neglected and pushed to the side by the MTA. This is frequently done to uptown stations because they are communities that are predominantly made up by people of color and since it is not a popular tourist location, there is not a lot of importance put toward these stations and they are not frequently maintained.

For my proposal, first, I thought about fixing up the station by cleaning it and by adding proper ventilation throughout the station and air conditioning in the elevators. I would also similarly redo the floors and continue maintenance of the station more often. Since the Washington Heights community consists of a dense black and brown population, the frescos will depict day to day people from the community along with public figures and people from New York City that are now successful. This includes New York City activists, community leaders, and known individuals that are doing things for the community. In particular, the Frescos would include people like Washington Heights native Lin Manuel Miranda, Bronx native Cardi B, Dascha Polanco, and Alexandria Ocasio. Overall, I want to integrate people that represent black and brown communities. Artists, activists, musicians, politicians, and every day black and brown folks would be incorporated into the Frescos.

“NYCHA x Local Graffiti Artists by Anika Hartje

My proposed monument will be various graffiti murals to be painted by local artists on New York’s public housing across the city, first focusing on areas with the most dense communities of public housing such as the East Village, East Harlem, the Bronx, Bedford Stuyvesant, and Williamsburg.

I wanted to force people to confront the way they view graffiti by transforming the rundown, littered, uncared for, and dark exterior of New York’s public housing into beautiful, politically charged graffiti murals.

One of the most exciting parts of this proposed monument is the free interactive app created in partnership with NYCHA. The app would offer a self-guided walking tour that would take locals and visitors on an epic journey through the city to understand how these themes are relevant and important to New York’s culture and communities.

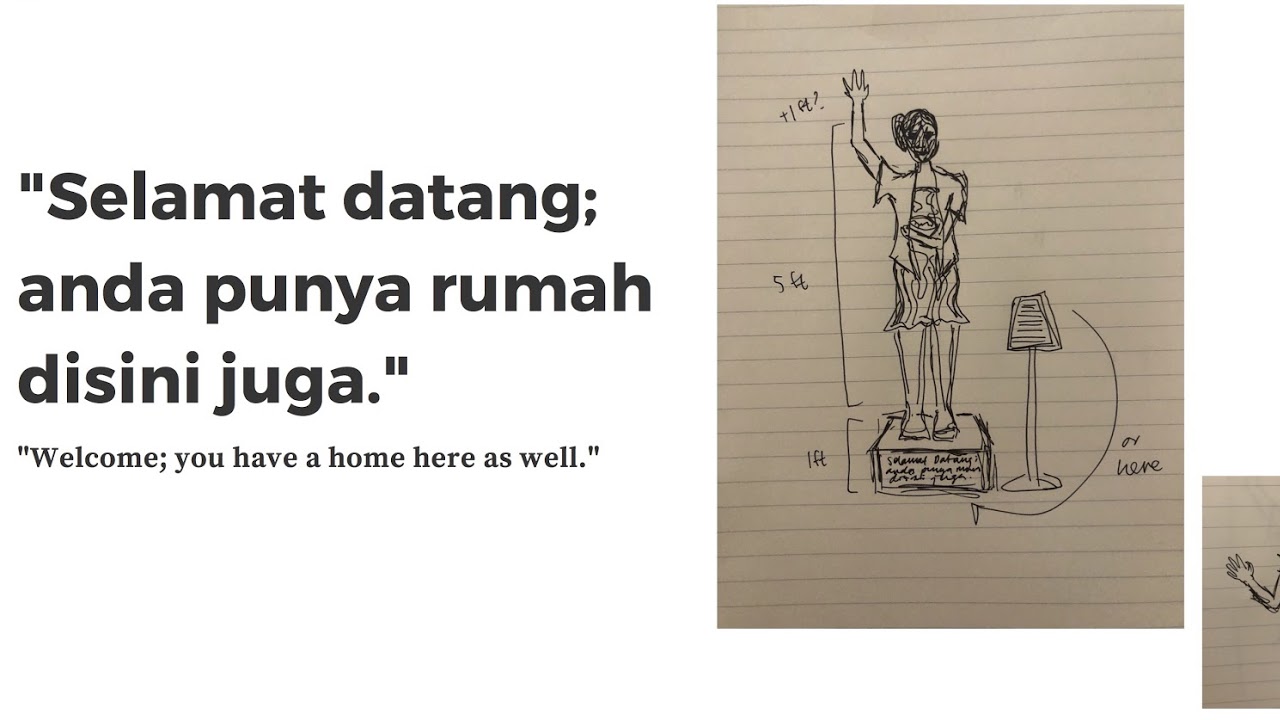

“Selamat Datang” by Fila Oen

When asked about what we would want our monuments to honor, I thought a lot about the unrecognized members of our communities—people who aren’t heralded as heroes and whose labor and efforts may go unnoticed. Immediately my mind turned to the Indonesian immigrant community in New York City. How could I honor them in a way that paid homage to their resilience in the face of the violence and turmoil that propelled them out of their homelands, while also recognizing the community they helped build and the lives they touch in the present?

Looking for inspiration in my hometown of Jakarta, Indonesia, I ended up digging into the Selamat Datang (“Welcome”) Monument, one of the city’s more notable monuments and a site I spent my entire life passing by without sparing a single thought. The monument was constructed in the early 1960s, part of a series of several constructions and city beautification projects commissioned by Indonesia’s first President Soekarno in preparation for the Asian Games IV. “Tugu Selamat Datang” depicts two bronze statues of a man and a woman waving in a welcoming gesture, and the woman holds a flower bouquet in her left hand. The statue’s design evoked similarity with the art style of socialist realism which characterized much of the art produced in the USSR. Art under this style was proletarian—art relevant and understandable to workers, typical—depicting scenes of the everyday life of the people, and realistic—in the representational sense.

I quickly learned of the connection between the statue and the political tensions that would soon lead to an incredibly violent period of Indonesian history.The Tugu Selamat Datang was erected shortly before Indonesia’s transition to the New Order, the ousting of socialist President Sukarno and the commencement of US-backed dictator Suharto’s thirty-one-year Presidency. It was an incredibly tumultuous period characterized by the purge of an estimated five-hundred thousand to three million Indonesians by the military (a slaughter still not discussed in history books or taught in schools out of sheer fear), economic crisis, and later racist, anti-Chinese riots. These were incredibly violent, tumultuous, and at the very least uncertain times, and when the US opened its borders with the Immigration and Naturalization Act, many Indonesians fled the country out of fear for their lives, settling in cities like New York.

To be placed in Elmhurst Park, amid a large Indonesian community in New York City, the monument would depict a woman holding an Indonesian dish in a bowl in one hand and extending the other out in greeting. The statue would be bronze and life-sized, maybe five-foot tall, and raised on a small pedestal about a foot high so you could look up to it slightly but it’d still be at eye-level and approachable. The text on the pedestal of the monument would read “Selamat Datang: anda punya rumah di sini juga” (Translation: Welcome: you have a home here too.). I’d want to include a plaque accompanying the monument to give it context. I want to explicitly state that this monument and its inscription isn’t to align Indonesians seeking political refuge with the U.S., a country whose military actions and foreign policies orchestrated the violence that unfolded and devastated countless Indonesians. I want the monument to recognize the space Indonesian immigrants have made for themselves as a home. I want to recognize what’s unique about each immigrant’s individual circumstances, yet also help build solidarity between the diaspora and those in the homeland.

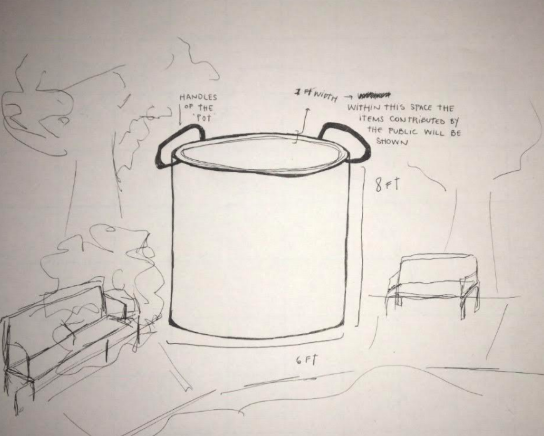

“Queens of Queens” by Clare McDermott

A successful and meaningful work of public art is one that speaks directly to the community in which it exists. I wanted the message of my monument proposal to depict as many personal histories as possible. This led me to think about a conversation our class had about portraiture, and who we would choose to commission a piece for, if we could choose any one woman in history. Almost all of the students resonated with the idea of having a portrait of our mother/ mother figures. Though we had all grown up in different environments, and have individual family histories, the idea of honoring the mother figures in our lives felt meaningful.

That being said, it was difficult to conceptualize a symbolic representation of motherhood (which, in many ways, is so individualized) that could resonate with an entire public. The first step of the creation of the monument, which I named “Queens of Queens” would encourage members of the community to contribute an object or artifact that represents a memory of their mothers/mother figures. Every day there would be an allocated slot of time in which one of the administrators of the project would collect the objects. Once enough material is accumulated to build the sculpture, the objects would be bonded together in a cylindrical shape.

This would be protected by two sheets of plexiglass and embellished with two handles at the top of the cylinder, mimicking the look of a large cooking pot. I chose this form for a few two main reasons. Firstly, in considering the symbols and associations that encompass motherhood that could be as universally understandable as possible, I resonated with the idea of food and being fed—a job that is often undertaken by the mothers/mother figures in one’s childhood. Food is also a tool for ritual and tradition, representing the passing down of histories and cultures down to next generations.

The monuments would be placed in front of the New World Mall, Travers Park, a small (unnamed) park-area on Roosevelt Avenue, and Astoria Park, respectively. I also wanted to place these pieces in diverse neighborhoods, because the majority of currently existing monuments in the city depict white (cis/male) figures. I focused specifically on four neighborhoods: Flushing, which has a prominent East Asian population (Chinese/Taiwanese/Korean), Jackson Heights (which has significant Middle Eastern/ South Asian/ Central and South American communities), Woodside (known as the little Filipines of NYC), and Astoria (which houses large Greek and Eastern European communities).

“Remembering Princess Deokhye” by Clarice Lee

Deokhye Ongju (1912-1989), the last princess of the Korean Empire, is one of the many women who were systematically erased, and forgotten throughout history. For this reason, I want to honor and commemorate her through my monument.

Born in 1912, two years after the annexation of the Korean Empire to Japan, Princess Deokhye was not recognized as a princess until 1917. She was taken to Japan at the age of fourteen, where she was ostracized and began to suffer from a mental illness that would today be recognized as schizophrenia. She married into Japanese mobility, but their loss in the Second World War, rendered her position meaningless. She and her husband divorced, and he disappeared shortly thereafter, which exacerbated Princess Deokhye’s condition. Princess Deokhye was only invited to return to Korea in 1962. It is said that she cried while approaching her homeland, and still remembered her court manners after 37 years.

From a young age, Deokhye was taken from her family, stripped of her national identity, and forced to learn the language and culture of her colonizer. Every article I have read about Princess Deokhye emphasizes and focuses on the tragedy of her life: it is almost as if the two words “Deokhye” and “tragedy” go hand in hand. While I want to stay true to the events of her life, I do not want to commemorate her in this light. want to memorialize her as the princess of Korea wearing the traditional royal hanbok: who she always was at heart and yearned to be, but could not be.

My monument would be placed in Koreatown, Long Island, since it holds one of the largest Korean populations in the United States. The Korean community in New York is composed of immigrants, Korean-Americans, or in my case, international students, and more. Despite the diversity within the community, we all share a longing for Korea whether it be Korea as a home, family, or a missing identity. For this reason, I want my monument to both commemorate Princess Deokhye and provide a space that could foster solidarity within the Korean community. In order to achieve this, the monument would be constructed out of stainless steel to allow passersby to see their reflection in the statue: they would not only see Princess Deokhye but see themselves in her. Furthermore, there would be a kiosk where people could sit and write their experiences as a Korean living in New York. Upon their choice, they could either keep their memos or post them on the kiosk for others to read. Through this individualized but shared act, I aim to transform the public space into a liminal space that could allow the viewers a moment to reconnect with themselves.

Monuments not only represent the past, but also the present and future as they reflect what we inherited, believe in, and celebrate. The story of Deokhye Ongju will not act as a reminder of a painful history, but symbolize an inheritance of patriotic solidarity, identity, and community that lives on in the present and will be carried on into the future.

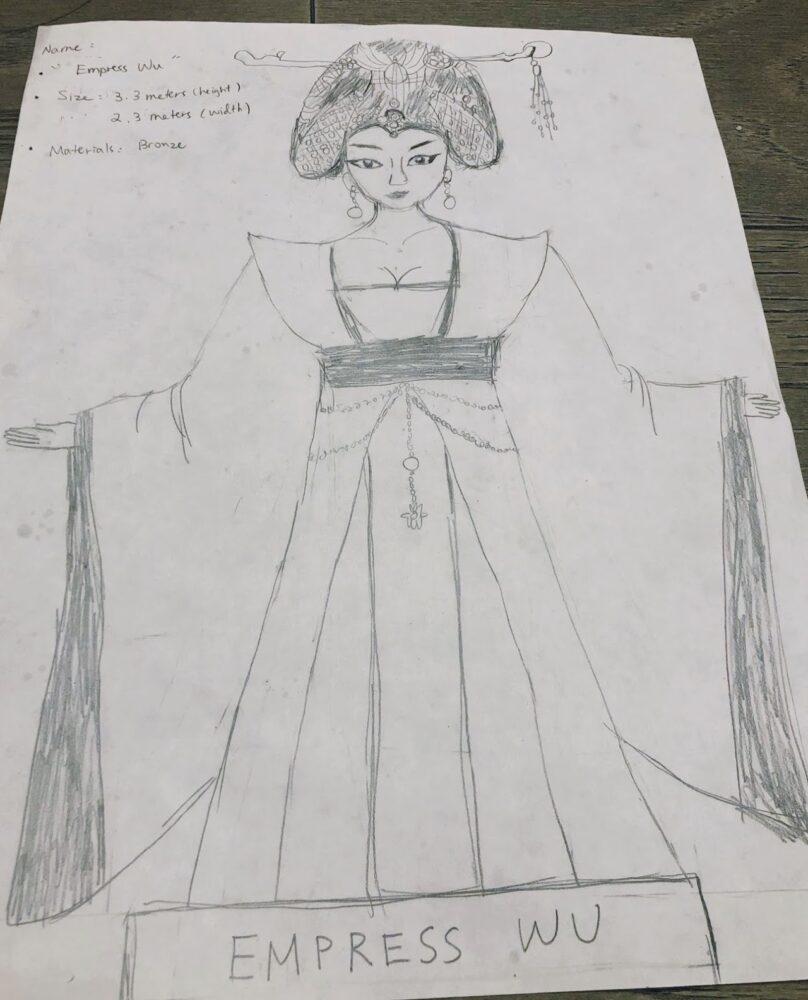

“Empress Wu” by Evangeline Lou

East Asians are widely underrepresented in the states, and one of the aspects that can illustrate the issue is through the scant number of monuments related to Chinese culture. According to the NYC Parks site, there are only three monuments that are associated with Chinese figures, and among those three, none of them are about a female character. Therefore, I propose a monument to one of the most controversial and powerful females and the first female Empress in Chinese history, Wu Zetian.

Wu Zetian (624 – 705 AD) embodies an example of a powerful and controlling female leader. The unapologetic attitude of a powerful female ruler is not often associated with Asians in Western culture. Using Empress Wu’s image to challenge the expectations of what an Asian woman should be like is highly valuable.

The appearance of the monument would be intimidating. First, looking at the monument, the audience should be able to know that the figure is a powerful ruler. In order to highlight the contrast of the stereotypes between what people usually think of Asian, the size of the figure would be twice as large as an average human being to express the over-empowering characteristics of the figure. There would be a two-meter base beneath the figure of Empress Wu, and the figure itself would be made of bronze. Empress Wu would be wearing a heavy traditional garment on the head to represent sovereignty. Her eyes would be glaring at a far distance into the sky, showing how almighty she is.

“Monument to Monica Helms” by Cameron Sopala

I am proposing a monument to honor Monica Helms; she is a trans activist and the creator of the transgender flag. Her monument would be a bronze statue in Helms’ image and would stand on a pedestal along Seventh Avenue in the West Village in New York City, modeled after the copious amounts of classical-style bronze statues around New York and America as a whole. A plaque would explain her significance.

I deliberately want it to be a simple, classical-style statue to subvert the notion that the only people who get monuments of them are old white men. The vast majority of traditional, permanent monuments are dedicated to old white men, and even though there has been a recent effort to include people in different communities, almost all of the monuments across the country are still old white men. There are incredibly few monuments dedicated to women, and even less dedicated to women of color. The monument dedicated to Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera will be the first monument of transgender people in the U.S., let alone transgender women of color, and although this is a massive achievement for the transgender community, we need more forms of transgender representation in monuments than the most famous transgender people in U.S. history. We need to recognize and memorialize activists while they are alive for supporting their communities and doing history-changing work for and within them.

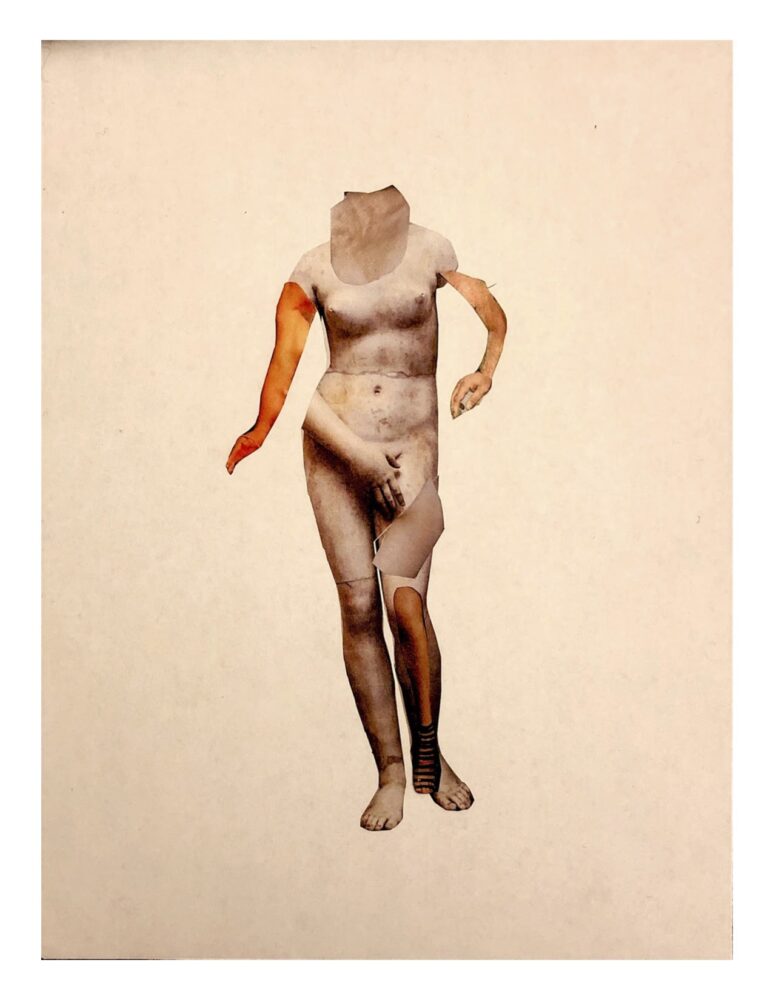

“[RED]EFINE” by Grecia Fuentes

A woman’s connection to her sexuality and her sexual desires is one that I wish I could have nurtured from an early age. I feel as if I could have been so much more confident now if I had been taught or saw within art, history, or pop culture that I should not be ashamed of or even sacred of sex. But instead, I was afraid of what a man might think of me or do to me. I felt like I was not allowed to be accepting of my body. I needed to hide it. So, I decided to design a monument that would honor the thing I always thought I needed to hide away: sex. More specifically, I wanted to honor those who were involved in sex work.

The Aphrodite of Knidos (fourth century CE) was the first statue to represent the female nude, and it conflicted with the containment of the women in Greek culture. The Aphrodite of Knidos opens herself up to voyeurism in order to allow her female viewers to tap into the same sexual power that she evokes while also having power over male desire. This power is similar to that of sex workers, yet the attitudes toward the Aphrodite of Knidos and the attitudes of those involved in sex work differ greatly in society.

My monument, [RED]EFINE, to be installed in Madison Square Park, includes five specific elements: the sex worker symbol, the female body and the nude, the Aphrodite of Knidos, the invisible barrier, and love. Firstly, I wanted to create a model of the nude body, however, I also wanted to be inclusive to many body types and to the fact that not all sex workers are women. So, I turned to photo collage in order to construct a body containing different aspects in order to involve as many different types of the nude as possible. I envisioned the collage to be life-size meaning that it would stand at about six feet or seven feet and at eye level, so people would be able to get as close as possible to it.

Additionally, there would be a neon light outline of a red umbrella hanging on top of the collage. The red umbrella not only is the sex worker symbol, but it also signifies protection for the body from elements that wish to harm it and the red color signifies love. The neon light would also be visible at night allowing for the art installation to not be forgotten. Plus, at night I envision there to be affirmations or words of self-love projected on the collage, in the hope that it would inspire people to view their bodies in a positive light. Lastly, I would encase the collage and the neon umbrella in a glass box to symbolize the invisible boundary that separates sex workers and their nudity from the praise that is given to nudity in high art like the Aphrodite of Knidos.

“#MeToo Movement” by Mina Kim

I would like to propose a monument built for the #MeToo survivors and supporters. This monument would not only represent the brave survivors, but also give strength to other victims still struggling. Instead of making the monument about a certain historical figure, I wanted to create an opportunity for all the courageous survivors to be represented.

At first, when looking at posters for the #MeToo movement there was an image that stood out to me: three raised fists of different people of color with red nail polish. The raised first, a symbol of solidarity and support, is an image closely related to the Black Power Movement. With that in mind, I decided to create a monument of a raised hand. The raised hand will be in pink and a projector will showcase the survivors and supporters name from the ‘#MeToo movement. The hand will be on top of a black marble platform and have a plaque that gives information about the #MeToo movement. The monument will be placed at Columbus Circle next to the USS Maine monument. This location is the main stage area for the Women’s March in New York City. The monument will have an interactive portion by informing people on the plaque that they can put their name through a website accessed through a QR code, where people will be able to input their name on the screen and ask to donate to support the #MeToo movement. I am hoping that this monument will bring more awareness to the sexual violence and harassment people go through every day.

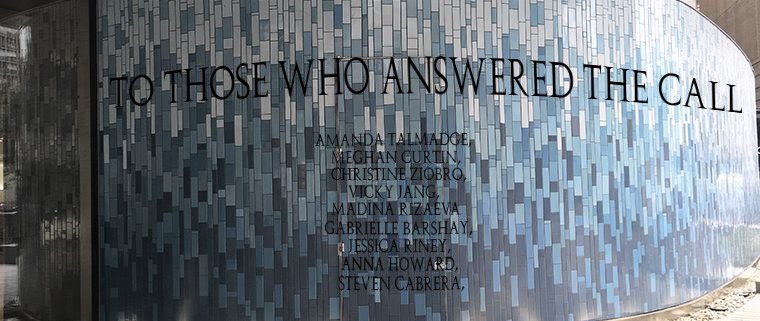

“To Those Who Answered the Call,” by Caroline Meredith

As a global pandemic upends every aspect of life, it is natural to dive into the history books and explore how humans of the past survived and moved beyond their own plagues. One harrowing case is the Plague of Athens, a medical disaster that occured around 430 BCE and was responsible for the death of approximately 75,000 to 100,000 Athenians, or one-third of the population. What we know about that pandemic today is largely because of Thucydides, a Greek historian who survived the disease and chronicled the major event of his lifetime, a decades long battle between Athens and Sparta, in the eight volumes that make up The Peloponnesian War.

Some aspects notably absent from Thucydides’ account of the Plague of Athens are the actions, responses, and achievements of Athenian women. So often, heroism is characterized in literature and memorialization by violent acts of warfare; therefore the Athenian women of the period, unable to regularly fight in battle, had no opportunities to display “courage.” Women endured rape, slavery, and torture during the Peloponnesian War, and yet their resiliance is hardly remembered. The time has come for caretakers (particularly those who identify as female) to be remembered for their courageous endurance. It may be too late to personally thank the women of fifteenth century Athens, but as another plague terrorizes our world, New York City is in need of a memorial that recognizes and celebrates the health care heroes among us.

I propose that we honor the dedicated nurses of NYU Langone, a hospital that treats hundreds of Covid-19 patients daily, currently working tirelessly, often placing the health of their patients above their own.

The monument will be a projection placed on the blue facade of the Kimmel Pavilion, at one of the hospital’s entryways. The monument will read To Those Who Answered The Call, a reference to nurse Steven Cabrera’s statement in the Times that, “We (the nurses) were part of a collective force that overcame something huge. We were the ones that answered the call.” In addition to the team of nurses that are cited in the Times article, the names of nurses to be nominated by the public will be placed under this phrase. The monument will only feature these words in simple black font, allowing for it to be displayed at all times.

“Peace of Mind” by Brandon Leo

I was inspired to create this monument after watching a video of an Asian-American healthcare worker, Dr. Chen Fu, thirty-one, who is a hospitalist at NYU Langone Medical Center. For Chen, working in the medical field throughout this pandemic leaves him with a bittersweet feeling, and he describes his experience by saying, “in the midst of all of this, it’s really, really, strange to me being both celebrated and villainized at the same time.” As a healthcare worker, Chen is praised for his work in fighting against the Covid-19 virus, but at the same he struggles with being denigrated by some for being Asian. Chen explains that, “people of my ilk are experiencing tensions that they haven’t experienced in modern history,” signifying the prevalence of difficulties regarding xenophobia that are currently arising in the United States for Asians and Asian-Americans. I designed this monument to honor Dr. Chen’s respect for the kindness that he is given by the people that care for him.

The primary goal of the monument, as a sticker/decal, is for shops or homes to show that they support racial unity and that they will band together to face the tough times ahead. The sticker also serves as a sign of peace and safety for those being racially targeted right now, allowing them to enter “safe spaces” whilst they perform their daily essential routines.

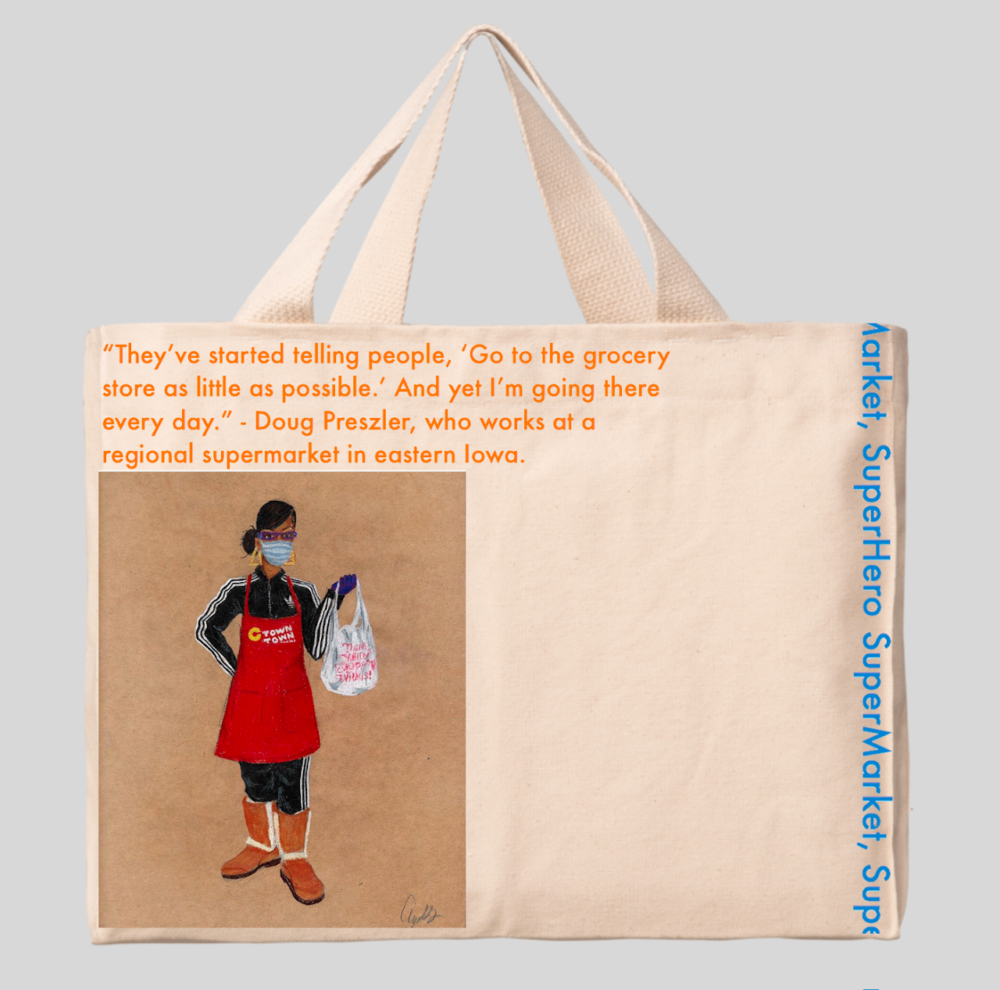

“SuperMarket, SuperHero,” by Isabella Cohen

The City of New York has been deeply affected by the current Coronavirus pandemic, and those working in this time of crisis are in dire need of more resources to sustain themselves and stay safe. The system currently in place does not allow these workers to take the utmost precaution, maintain their livelihoods, and keep their families safe. I have chosen to memorialize these front line workers, more specifically grocery store workers, to give them presence in a space which has seemed to have otherwise forgotten about them, their contributions, and their rights.

My memorialization will occur in a less traditional way than a bronze statue per say, but will rather consist of real grocery store employees and quotes of theirs printed on reusable shopping bags under the brand/slogan “SuperMarket, SuperHero”. These bags will be distributed to each major retailer beginning in New York City, as well as smaller businesses/bodegas, on the premise that the 100% of the proceeds obtained will go to the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union (UFCW) to allocate more resources and advocate for policy change. The bags will look like regular grocery bags, but will be made out of sustainable fabric and will have comfortable straps attached.

The designs of the bags will mainly be focussed around artwork from different artists’ representations of the coronavirus, as well as quotes or statistics of how front line grocery workers are treated printed on one side of the bag, so any major grocery stores have the option to place their own logo and possibly even a supportive quote on the other side. This will allow for the community to be involved, as they can champion for their own stores to carry the bags, submit their own designs, or even vote for their favorite bag they’ve seen or purchased! To have art as the design for these bags is important to me, as artists are workers who are also having to defend their livelihoods in this pandemic, and to give a voice to artists who soothe the world through their representations is almost like a no-brainer. All of these actions will promote the idea that grocery store workers are not only essential, but should be treated as such. The bags will first be distributed with three different patterns and as the popularity grows, so will the designs with help from those submitting their own designs.

“Monument to Essential Workers,” by Ava Kahar

In the face of international suffering due to the coronavirus epidemic arise those who keep society running as functionally as possible: essential workers doing mail, food, and medicine delivery, among other necessary products. Without these hardworking, invested individuals, the economy would be crippled, more people would suffer from lack of resources, and more people would become infected.

I feel that a monument to these workers, who are putting their own wellbeing on the line to aid the public, is essential to processing equity in these times. While delivery service usage has surged overall, many of the people who are able to afford delivery services for necessary and other goods and otherwise are in a relatively stable monetary condition compared to the majority of people who have lost their jobs or fear using extra money on delivery. The monument will serve to allow people who are privileged enough to order delivery to recognize their place in society and appreciate the essential workers who may not be in as secure of a position.

Installed in Riverside Park at 106th Street, the bronze monument would take the shape of a four-foot tall, four-foot wide, and six-foot long rectangular cardboard box, one of the most common receptacles for our beloved deliveries. The bronze will allow the monument to be a long-lasting piece with some similarity in color to cardboard, also designed to resemble the texture of cardboard. Open at the top with the four sides of the box hanging open, one will be able to see some items peeking out and take a further look inside of the monument to discover more common items that people are having delivered in these times. Depending on the community’s input, the monument may depict fruits, vegetables, toilet paper, and disinfecting spray, all necessary items that are hard to acquire during the pandemic, made of painted bronze to reflect the physicality of each object.

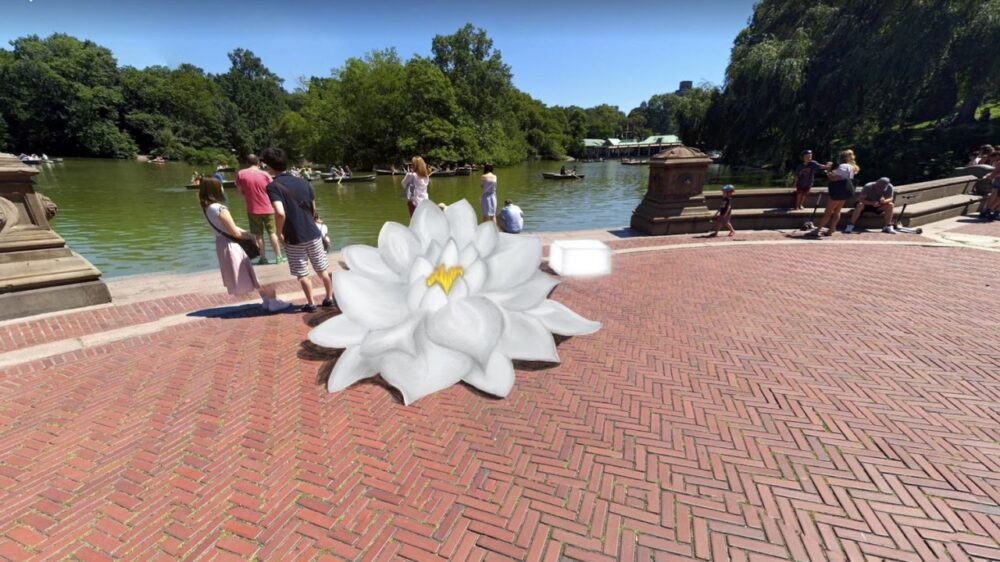

“Angels of Our Waters,” by Calli Ferguson

How might public art make space for the heroes of this monumental time in history–the essential workers, who are overwhelmingly women, immigrants, and people of color–to tell their own story? With this, I looked to existing works of public art in effort to communicate with the city’s existing cultural and physical landscape. One that stuck with me, both for its symbolism and history, was the neoclassical, eight-foot tall, bronze sculpture, Angel of the Waters, standing in Central Park’s Bethesda Fountain.

I want to create a story that speaks to the Bethesda Fountain, but is dedicated to the “Angels of Our Waters” who are, in fact, human beings. My monument will sit directly between the Bethesda Fountain and the central pond as to communicate a sort of timeline for sickness and rebirth.In further effort to create a dialogue with the existing work, I will use a key symbol from Stebbin’s sculpture. In the Angel’s right hand she holds a water lily which is used to symbolize the healing properties and purification that she bestows on the water. This symbol will be the subject of my monument as not to anthropomorphize the totality of many different people who are working to bestow health and wellness upon us today.

The plaque would direct visitors to a URL, It would appear on the screen as a body of water down which you (the viewer) could scroll, sprinkled with water-lily graphics. Clicking on a water lily would then pull up an essential worker’s self-chosen image and their first person narrative story of the Coronavirus Pandemic. There would be a space on that website for essential workers to submit their story and image, populating the website with a variety of perspectives. These people and their personal telling of this time in history would then be memorialized by the water-lily statue and inscription in New York City’s Central Park. Thus, we can find a way for history to be told by way of the individual as well as the collective–providing space for those who should be writing and written into it at this moment.

“An Interactive Monument” by Angelica Richardson

This monument is a dedication to women, the unsung heroes of the world. But how does one make a monument to celebrate such a diverse group? I wanted a symbol that could emphasize the individual while uplifting a community. Representation for all women, no matter their sexual orientation or nationality.

Where is the perfect place to build such a monument? In every city around the world there exists an unappreciated woman, so this monument needs to travel, to grow with every city and every encounter.

How do you make a monument interactive? For me, interactivity is defined by having an audience change or add something within the piece, It’s not just pushing a button or following a path of options already selected for you.

Through these ideas I settled on a large sphere-like object, like a globe. It spins on an axis when pushed like the force women have to persevere through many injustices.

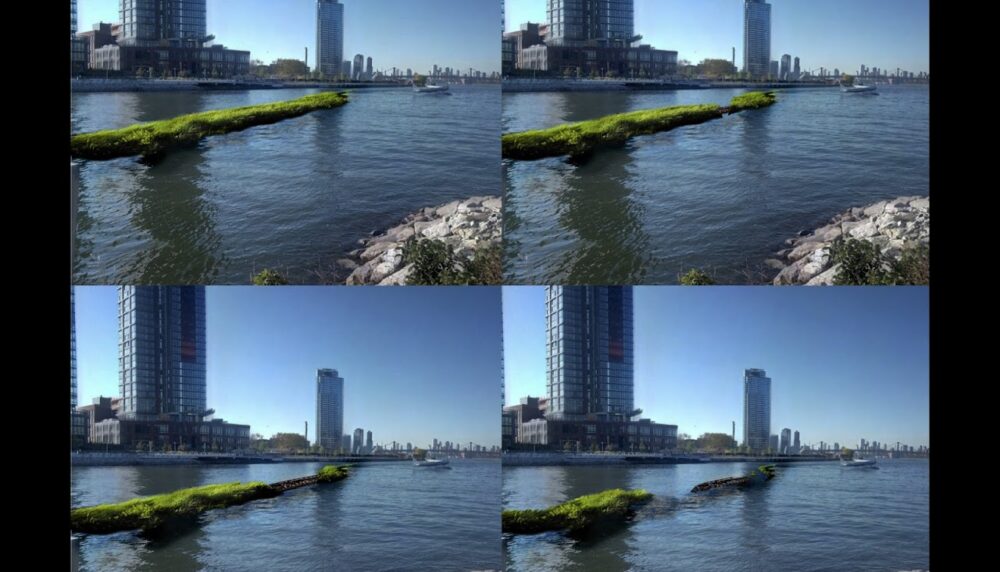

“Geographical Monument” by Mikella Tyler

The concept for this monument proposal is to memorialize the land of New York City as land, not untamed, for humans. But indicative of the transformative geographical history of Lenapehoking and then New York City, the land was changed, and this should be recognized.

For this monument, land shall be used to pay homage to land. This choice is not based on the feminine associate with typical portrayals, or a way to circumvent the use of women and femininity in a monument. Instead, this monument lends to other intersectional feminist ideology—of rethinking history, recognizing human pitfalls and burdens, reclaiming ideas about land usage and productivity, and facilitating conversations through unconventional means of representation. Thinking about ecological heritage, this land monument uses plants originating from the Northeastern US—wetland grasses, juniper brush, brackish algae, to indicate the deep history of the region’s environment.

The location plays a significant role in the meaning of this work. Bridging Southwest Queens (Long Island City) to North Brooklyn, Newtown Creek is fraught with a deteriorating geological history. The site of constant human docking, waste dumping, and negligence, the waterway remains highly concentrated with pollutants and toxins. The monument will recognize this altered environment of the site, as the land bridge will deteriorate over the course of ten days from the middle outwards. This process is possible through the use of a water soluble algae base structure, that is thick enough to last for the first few day, then will start to give way from decay.

This monument hopes to understand and represent the changing lands of New York City, considering ecology, environments, and geography that’s historically forgotten and overlooked.

Thinking about abruptly changing geographies, the work demonstrates the actions of use, pollution, and deteriorating over a ten-day process. In considering everything for this monument, a name has yet to be chosen. Possibly this could be chosen by the neighbors where it is located. Or maybe the Lenape word for island, mënatink, a reference to both precolonial ecology and the words of ancient Greece that feminize land. Also something like nostos, Greek for “return home,” a literary theme in ancient epics of a hero coming back from sea. While the name is undecided, the monument remembers land with a bridge to connect to the geographically changing past, and to comment on rapid continually changing futures.