“I ‘plantation-hopped’ around Georgia in hopes of answering a lifelong question: How is it that the descendants of plantation life can look back on the remaining spaces and see such different things?”

Plantation Vacation

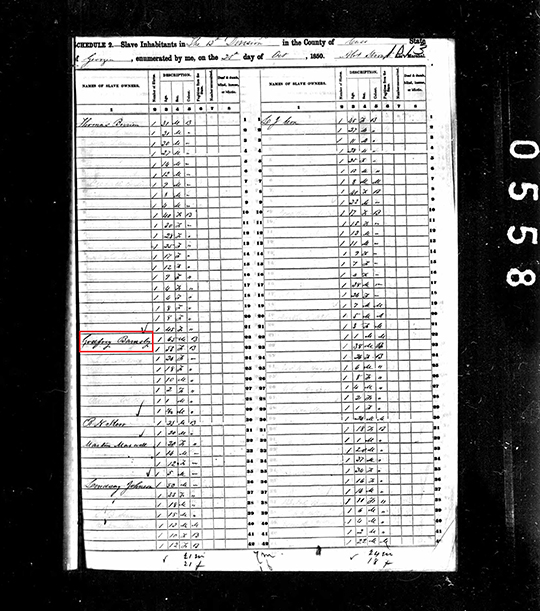

My story starts with slavery. I am part of the fourth generation of freedmen on my mother’s side of the family—most of us haven’t moved very far from the Georgia plantations where our ancestors resided. My father’s maternal side has a slightly longer lineage of freedom, as slavery was abolished in Barbados in 1834, while his paternal family was scattered around a few Virginia plantations. I still carry the name of their owners.

The confusion came at a very young age. I drove by white mansions with Tuscan columns—authentic and replicated. My friends’ subdivisions had names such as “The Plantation” and “White Columns.” I was a Southern Belle for my fifth Halloween. I went to my first plantation resort when I was six. Yet, my family would always tell me stories about how slaves were beaten, tortured, lynched, separated from their families, stripped of their identities. They explained how our skin became lighter than our African brothers and sisters. We took trips to exhibits and libraries. My mother sat my cousin and me down during our summer break from elementary school to show us Roots.

I envisioned myself on Tara, and it wasn’t in a ballroom. When a Baptist preacher started reminiscing about the “golden age,” I couldn’t nod along at the sermon’s pining for “mint juleps on the porch.” When a bank teller raved to my mother and me about a plantation resort we simply had to visit, I realized that her memory of such a space had been cleansed of any remnants of brutality. I began to ask questions as I tried to blend these clashing visions.

How were plantations both places of suffering and romance? Places people revived through architecture, nomenclature, and cotton blossom decorating trends; places whose existence relied on the denial of humanity?

I “plantation-hopped” around Georgia in hopes of answering a lifelong question: How is it that the descendants of plantation life can look back on the remaining spaces and see such different things? What is the relationship between the presentation of plantations and our memory? My curiosity left me with emotional exhaustion, discomfort, and fear. I never used pretenses, but at times, I felt that trespassing and penetrating the “romantic side” was worthy of guilt. A black person simply doesn’t hold that sort of dialogue with plantation guests and employees—especially when the prominent owners are wandering the property. What if I got “caught”? Candor soured into suspicion when people seriously considered my complexion—Clent, whom you’ll meet, was particularly wary of my presence.

This project is my attempt to show a historical space through the blended lens that I have grown up with. The following excerpt focuses on my visit to Barnsley, a resort that epitomizes the coexistence of a Margaret Mitchell fantasy and the pain that is literally embedded in its masonry.

Robin, My Mother

I never really saw a plantation growing up, but just the thought of a plantation made me feel really eerie and uncomfortable. When I was a kid, I envisioned hundreds of acres of land, with blacks everywhere and overseers whipping them. I also imagined slaves living in hut-houses and their masters living in a mansion with columns on it, and a wrap-around porch.

My great-grandaddy on my mom’s side was born a slave. I know that slavery ended in 1860-something, I’m not exactly sure what year. But my granddaddy was born in 1901—[his] dad was a little boy when slavery was ended.

I don’t think people really consider what happened on the plantations. I don’t think they even really consider the name. Like Reynolds Plantation. Right now, it is a Ritz Carlton Hotel. And I know that a lot of people now will include “plantation” in their title because they think it makes it sound grander. It seems like the homes have a lot of stature. Grandioso. Even a lot of black people don’t think that deeply about it, because I hear a lot of black people say that “I have my own plantation.” They don’t think twice about it; they don’t consider what the plantation meant to us as black people. And I also think that when black people say, “I have my plantation,” or, “You have your own plantation,” usually, the connotation is that you have a lot of land and you have a huge house. They steal that from slavery.

One of the students in my class told me that she and her family had been to Barnsley, and how beautiful the gardens and the cabins were. I looked it up, and I looked at the cabins, and they were pretty. Then I decided I wanted to go on vacation without doing any research. And when we got there, I realized that it was a slave plantation.

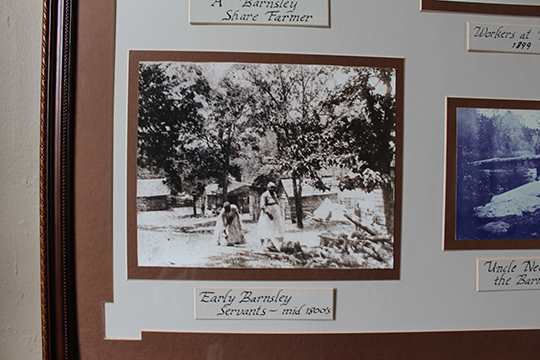

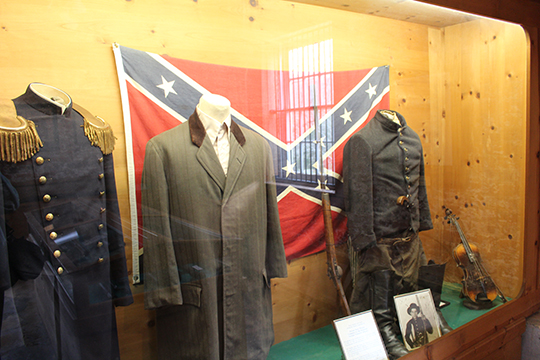

I don’t know—maybe I had an idea. I guess to hear that you can stay on a plantation is different than actually going there and actually seeing the houses that the masters lived in. I felt very eerie. And then just being there; just walking through all the grass and actually realizing that you’re on a real plantation. The structure had been partially burned down—but it was there. In the basement, you saw actual dishes and a Civil War uniform from the South, guns, the kitchen, some pictures of the people who actually lived there.

Based on what I remember, I didn’t see any evidence of slaves. I didn’t see any evidence of slavery period. If I didn’t know that slavery existed, I would’ve thought that it was just a quote-en-quote “big plantation,” meaning just a big lot of property for farmers.

We don’t talk about it. If you don’t talk about it, if you don’t have pictures of it, and then you change the terminology, too: instead of saying the “masters,” the “owners” of the property. And then you say the “planters” of the fields, the “workers.” And workers are not significant. Not like the owners are. So you get rid of everything about how the slaves actually worked or lived—don’t even talk about ’em. You pretty much just talk about the owners of the property. And their successes.

Clent, Barnsley Resort Founder and Archivist

So many things happened here: The adventure. Romance. And some mystery. One of the greatest love stories of the Old South. Strong women. In every generation.

All the people here—not only the Barnsley ladies, and the daughter of the estate—but the Irish people here, some Cherokee Indians, and some African Americans. And it’s a strong women’s story in every generation.

Barnsley was a British subject—he never became an American citizen. He was born in England, came to this country when he was 18 years old, had nothing. Went to work as a clerk for a large shipping broker in Savannah. And within fifteen years became the wealthiest sea merchant of the South. And he was a big importer-exporter. He usually shipped cotton abroad—he didn’t grow cotton; he never planted a cotton seed in his life—but he shipped it overseas and then loaded the same ships back to this country with European commodities. And he built such a good name for himself and did so much for this country and for trade, that the president of the United States appointed him Vice Consulate for three different nations. Although he never became an American citizen.

But he did marry a citizen in Savannah in 1828: Julia Scarborough. And the story moves on, and he wanted to build her this fabulous estate he had planned. But he wanted to build it in a cooler climate, away from the heat in the lowlands. And so what was going on in those days up here, this was Georgia’s last Indian frontier. Everything north of Atlanta was still owned and controlled by the Cherokee Indian nation for over a hundred years. The whites were coming up here, some of ’em, and marrying into Indian families, and they allowed that, but you lived under their government, and their rules—not ours. So our government—both state and federal—wanted it all under their control. So they made a deal with the Cherokees, finally they got their lands. Divided ’em off into land lots at a big land lottery up here in North Georgia. Fifty-four thousand land lots. Each one of those 160 acres. And so that’s how they got up here. My family came up here and got involved in the lottery. Lot of the families did, but later on, some were willing to sell. ’Cause it was a long way up here, and it was pretty rugged livin’ up here in this wilderness in those days. So Barnsley came later and bought land lots from people that got ’em through the lottery. He had nothing to do with the Indian removal. And he had nothing to do really with the Civil War. He tried to remain neutral in that war.

Twenty-nine thousand Union troops camped on this land. And Barnsley was trying to remain neutral in the war. General McPherson saw this, saw how the whole setup was different here, and he ordered the place spared and protected. He was one of General Sherman’s generals, but not Sherman himself. Sherman himself was still on the railroad two miles down—he was pretty vicious. So General Davey McPherson found out it belonged to a British subject, and it was so beautiful, he wanted to spare it. But after he left, hours later, about a thousand of his boys stepped out of here and ransacked it. They didn’t burn the main buildings, but by the time they left, they left a hundred starving people. And Barnsley’s daughter Julia is the one who becomes the typical Scarlett and saves their lives. She took ’em into the woods and taught them how to dig roots out of the ground, anything they could to stay alive. So it’s quite a story here of the women.

Now, Barnsley wanted this to be a self-supporting estate. He made his money on the high seas and had to keep everybody running. He made a lot of brandy here. He had large peach orchards, he brought trees, plants, from all over the world. And some of the trees were hundreds of years old when he brought ’em in here. That’s one of ’em up on that picture right up there—that was taken in 1880. I took a black-and-white and colored it on a computer some years ago. And that ancient tree is still standing out there. It’s about three hundred years old now.

Through the years, wars, storms, depressions took their toll. Things happened. And finally, we’ve only saved a small portion of it. But I’m happy to say this much: This goes way back into my family. My great-great-grandfather helped build it, great-great grandmother born down the hill here. Our families went through four generations together. So I got attached to this as a little boy. Hearing the stories. And I finally went to work. When I finally ended up with thousands of the family papers and letters and diaries, and I started my interviews at a very young age. For example, when I was a fourteen year old boy, and Miss Molly Curtis down in Kingston—we called her Aunt Molly—she was dear African American lady. And she’s 102, and I’m fourteen, and I’m writin’ down her story.

Anyway, the last of the Barnsley blood died here. See, times were hard after that war for a long time. And we had problems in the South among ourselves. We had land barons who controlled people. Some of ’em started new forms of slavery called sharecroppin’. That kind of thing.

Julia had a daughter during the Civil War—Agnes—Miss Aggie is what I remember from when I was a little boy. And she had a family here. 1897, she married a chemist from Pennsylvania and had three sacred children. And the children grew up here tryin’ and strugglin’. See, it took the South so many years to get over that war; they were still strugglin’ financially.

Miss Angie had a stroke one day, died a few weeks later, and this debt was still hanging over the estate, and they ordered the place to be sold at public foreclosure and auction. At that auction, my family bought quite a lot of it. My grandparents, great-grandparents, uncles, great-uncles . . .A lot of the heirlooms and furnishings and papers and things—that was enough to get me started. So I got deeper and deeper and deeper into it at this time, moved on, hoping that someday we could save it. And after that auction, two different owners had this property.

By 1988, it was a jungle. I show a picture in the back of my book of what it look[ed] like when Prince Fugger of Germany purchased the last 1,300 acres of the land in 1988. And so I sure poured my heart out to him, and he had an appreciation for history—American history, Civil War era—things like that. And so then he came back and said, “Let’s figure it out.” So we went to work.

Through the ’90s, we talked about this becoming a resort, possibly. And Prince Fugger’s advisers suggested it would be a good place for a resort. And good investment. So he decided to do it. And so we went to work, built the resort between ’97 and ’99. Opened it up in 2000. And the cottages over there in the village, they’re Downing cottages from that Downing plant in New York. This guy that promoted it—he had Gothic cottages for villages, he had lots of things. And they were so different. So we built these Gothic cottages out of Downing’s books, basically. We kept growing, and then at the end of 2003, Prince Fugger sold it—you know in Germany, it’s not easy for him to get over here. The place is growing a lot, so he sold it to Mr. Julian Saul in the carpet business up in Dalton, Georgia, thirty miles up the road. And he’s been adding a lot more amenities to it. Lots more land. So we came from 1,300 acres up to about a little over 3,000. And while you’re here, you’ll see it advertised—Spring Bank Plantation—hunting club and estate. That’s right below us. And now that’s all part of this property. And now he’s adding new buildings over here, so we have a new Georgian Hall, a new Inn . . . In fact, we’re just opening right now. This week.

. . . Clent wasn’t particularly congenial. His assistant, who was eager to introduce us, was overcome with embarrassment when he initially refused to merely look at me and acknowledge my presence. Clent couldn’t bring himself to believe I was a guest at the resort. Even after I explained that I was doing a project for an oral history class, he questioned my motives. As I spoke to Bill and Elaine (whom you’ll meet later) after the interview, my mother kept an eye on Clent. She said he gave me a seemingly perpetual glare—one of a variety only minorities can truly comprehend.

Robin

I don’t have a problem with it being used as a resort. I think it’s just up to the individual as to whether or not they’re going to stay there. In Barnsley, everything was still so well maintained, and there were even bicycle routes around the plantation. And little gardens here and there. It distorts everything. I guess I see it as being romanticized. I never even thought about that before. Not necessarily romanticizing slavery, but plantations.

I don’t think that it’s making people forget. I don’t think that it’s making people want to bring back the old days when we were slaves and had masters. I just feel that a lot of the lot of people that own plantations keep them well maintained want to make some extra money. And people are interested, because of the way they maintain the property, and a lot of people like the antebellum-type houses.

Nancy, Employee

I’ve always loved Barnsley. And when I saw the opportunity to be able to work here, there was no mistake—I definitely had to take the opportunity! I’ve even come out here when I was a child on field trips. And I’ve brought my kids.

So much change, it’s completely different, but all good changes. Definitely the Inn has been the biggest change, cause pullin’ up, and this just bein’ here—it’s so crazy! And then the seasons, too, when it goes from winter to spring to summer, it’s just like everything comes alive out here. It’s just like it has its own magic or somethin’. It’s really neat. Winter’s very different. Christmas music playin’ everywhere, they have all kinds of special events, and they have all the lights when you go down to the ruins . . . it’s just . . . oh my gosh! It’s beautiful! They have all kinds of Christmas decorations and lights down there.

It’s a lot busier now. There’s local, but then there’s a lot of abroad. A lot. I’ve met all kinds of people today even: Ireland, Germany . . . You can tell that it’s a big culture shock to them. And they always say the same thing: they’re like, “Everybody’s so nice!” I hear that so much! I think it’s just cause there’s such a wide variety of activities and honestly, I think it’s the people. I think it’s just because everybody is so welcoming, and everybody just treats everybody like family.

Clent

We worked here for a long time just to save a little bit of it. We brought in a wonderful horticulturalist, Steve Wheaton, a blessing for us, who taught us how to save what gardens we had left. They were so old. See this one out here, it’s been standing here since long before the Civil War. I had to change the fountain, but the garden’s the same. I opened the museum with my artifacts. During the ‘90s, I was able to help transport more buildings here. Historic buildings from the North Georgia area. One of ‘em’s the Rice House and Restaurant over here. I moved that house about thirty miles from the next county. We cut it in four sections—picture’s in the back of the book on that—and we just kept going.

I knew that they would enjoy this property, because there’s a lot of stories behind it. So I want ‘em to see that this a different type of estate in the Old South and it was so beautiful at one time. It was the landmark of the South. Became a real showcase of the South. And the stories in each generation are all around. Like all families, there’s a lot of joy. Some tearful sadness. And a lot of things that happened through the years.

I have lots of people who come here who really just enjoy the story, the buildings, the history. It’s kinda like walking back in time. And that’s what I had always wanted it to be. To hear some stories of the past. And then I think that’s great in this modern world of technology that we have today—it’s wonderful, but we don’t need to lose touch with our history and foundation.

Denise and Larry, My aunt and uncle

Denise: Growing up, the only thing I knew about plantations is what my grandparents would tell me. My Grandmama Banks would tell us about plantation life. I just thought it was a place where people were restrained from being themselves, especially people of color. They were like property. They could not even keep their own children if the master wanted to get rid of them.

Great-Grandaddy Holsey was born in 1901 near Albany, Georgia. And when he came to Atlanta, he didn’t have a car—he came up with a horse and buggy. He and his brother were looking for work. And these white people from Florida told them that they had work for them. So they got on the back of a truck and they rode down to Florida tryin’ to get some work. And when they got to Florida, they put all the black people off the truck, and then they used them for shooting range. They were shooting at them and they had to run for their lives. So Grandaddy Holsey lived to be 102, and that’s because of God’s grace and God’s mercy, because they were trying to kill ‘em. And they hung his brother. I don’t know if he had done anything, but there is nothing that a person can be accused of doing that would warrant that type of repercussion.

I’ve visited a couple of plantations: Boone Plantation in South Carolina—they show the main house, and they also had some swampland. They had a narrow bridge to cross over. It was alligators in the water so that if the slaves were to try to escape and run away, they would be eaten. And then they had the slave cemetery. The man that was the overseer of the property was a black man—he and his family is buried in that cemetery. And during the Civil War, the owner left South Carolina and went to Tennessee, and when the Union troops came into South Carolina, the black guy walked all the way to Tennessee to let his master know that his plantation had been taken over by the Union military.

Boone was kind of eerie, ‘cause the plantation itself was beautiful! But they did have the slave quarters—you know, like one fireplace in the house, and they had mats on the floor. The mats was made with straw, or grass, or whatever you wanna call it. Then they had their cooking utensils, which is like a cast iron pot. I also went to Thomas Jefferson’s place outside of Washington DC. And his place had slave quarters as well.

Unfortunately, the South—they’re proud of slavery. Now, if it’s truly a plantation, you’re going to find evidence that there were slaves there. Today, we have modern communities that are called plantations, but they’re not truly plantations. That’s just a name they’re having for that subdivision or that area of land. When you go to a true plantation, you’re going to find evidence of slavery there. I have high esteem as to who I am and whose I am, so I can basically talk to anyone about slavery, as long as the conversation stays civil. I will not talk to someone that wants to talk down to me. I don’t feel that anyone is superior to me other than God. And as a matter of fact, I did discuss race and slavery: I went to this little island down in Brunswick, Georgia. Larry, what was the name of that little island we took a boat to? Where the black people refused to leave? And they were rice people?

Larry: Sapelo.

Denise: Sapelo. Sapelo Island, down in South Georgia. Once we got on the island, we drove around on a bus. And of course our tour guide was a white person, and 99 percent of the other people on the bus were white, and I asked, “Well, where are the cemeteries for the blacks?” And the guy said that they would show that cemetery on certain excursions. But he said whatever you liked in life, that would be your headstone. For example, if you liked to play harmonica or something, they would lay that for your headstone and then put a piece of wood with your name on it. So no, I don’t have a problem. If I want to know, I will ask. Now you know got a whole library over here of your Uncle Larry, and it’s all kind of books about real people and their stories of enslavement.

I feel that we were used and abused as a people. But I also know that when God told Moses to go and tell Pharaoh to let his people, the Jews, go, Pharaoh and his people were black, so the first slave owners were black people. And that’s Biblical. It’s in the latter part of Genesis and Exodus. It just tells me that life has cycles. And the life cycles are long cycles. And it just tells that life—the Bible—never fades. It goes in circles and in cycles, and at one point, we were the slave owners. Then we became the slaves.

And then what bothered me about slavery is the fact that our own people sold us into slavery from Africa. And the fact that we as a people could never seem to be united because of . . . I don’t know why. Today in the United States of America I know why, but why would we use each other when we were in Africa? Why did we sell each other into slavery when we were in Africa? But now I know why we are different from each other: because we were separated and we were not allowed to stay with our tribes when we were brought into the United States, because they didn’t want us to collaborate together to try to free ourselves.

Anthony, My Father

The only reason I went to Barnsley was because your mother [Robin] said, “Hey, let’s go here for a weekend!” I don’t remember seeing another black family the first time we stayed here. But when I saw the other black couple, it was great, because you kind of felt like, “Oh—there’s someone else here that’s like me!” It was a good feeling: relief. I kind of got the same sense from them! You didn’t see blacks enjoying themselves there.

I thought Barnsley was a nice place. But as a black person, you still kinda got a feeling of, “hmm . . .” You’re a little uncomfortable because of what the place used to be. You could tell from the clientele that there aren’t a lot of blacks that stay there. Although you’re treated fine, you just feel sometimes that you’re out of your element. I don’t know if I’m the only one there that saw the full picture, but because of who I am, I’m sure that my perception might be different from someone who is white.

They still maintain things: the house, the pictures. The only thing that was disappointing was that they didn’t call the slaves “slaves.” They called them “servants.” They kind of watered it down to make it sound like it wasn’t as horrible as it was. That’s why they’re still debating this today—with the Confederate flag, people say, “Oh no, that’s actually heritage—it’s nothing to do with slavery!” Which, you know, is a bunch of crocker’s air. It’s just like Bill O’Reilly said about the slaves who built the White House: “Oh, these people were treated very well! They were fed well!” They try to make it sound like everything was okay. But the bottom line is, they were owned! Just like a dog.

I guess when I go there, I try to keep an open mind and enjoy myself just like everybody else. I feel if they own the property, they can do it how they want. But at the same time, I definitely get the feeling of what the place used to be. We were, at one time, slaves here. I can feel that in the back of my head. I’ll stay there, but I realize what the place used to be. I can’t separate it, but if other people do, maybe it’s because they don’t feel it like we do. Even though all of us know the Holocaust, I bet you the impact the on Jewish people is heavier. The impact of slavery on blacks today is heavier than anybody else, ’cause that’s what we were a part of; we still suffer some effects from that. I wouldn’t expect a white person to feel that, because they don’t go through things that we go through.

I think that Germany has done a much different job than we did as far as what happened back in WWII. From what I understand, the Heil Hitler sign is illegal, the Nazi flag is illegal. And when I went to a concentration camp once, it was kind of eerie place. They didn’t hide anything. They did not water it down at all. Unlike the plantations here—slaves were like their family, and they were healthy…they don’t show them on a whipping post. I think it’s hypocritical. I wouldn’t say it makes me feel angry. It just makes me feel disappointed.

The slaves built the house. But slaves built a lot of structures in Washington, DC, and we go there. Our history is ugly. It would be nice if they acknowledged that—that would be more appropriate. In American culture, they always wanna water down what situations were back then. People are always gonna have a different perception. I don’t know why they do. It’s a shame.

Sheila, Employee

The animated Sheila manages the resort’s boutique. She pulled me into the dressing room to conduct the interview . . . You’ll see why.

I live in Cartersville. About twenty minutes. Even though I lived here mostly all my life, I’d never been here before. But my husband has been here to play golf, so the only thing that I knew about it was that it had a golf course. I worked in a school system—I was a secretary in the office. Then my job got cut, and so I stayed at home for three years, and then I thought, “Oh—well I gotta do somethin’.” So then that’s when I was like, “Okay, let me go check that out.” So that’s how I got here.

The first three months here, I never saw a black person. But there is some that work in the restaurants and kitchen. And then we went more corporate during the week, and so corporate groups would come and then I would begin to see you know, one or two. And now, it’s better, ’cause couples are coming—people are just finding out about Barnsley. You know, driving in from Atlanta for the weekend, or something. But I think it’s just people don’t know about Barnsley, ’cause this is the “country.”

It’s small, quaint . . . really, it’s so peaceful here. And it’s nice. And even when we’re at a hundred percent, you can never tell that it’s that many people here. People say, “Where’s everybody at?” I don’t know where they are, but we’re a hundred percent, and you really don’t run into a lot of people until maybe dinner or, you know, whatever they’re doing. And most people’s worried about when they built that Inn, especially the members. It’s a membership here, and it’s about twenty-five hundred dollars a year, and the members was like really angry, ’cause they said it was gonna change the atmosphere. And they come out once a month and have dinner, or they get to stay so many nights once a month, and they just have all these privileges, golf and little activities. But I think that it’s just a little hidden gem in North Georgia. You know? ‘Cause really, I can assure you most live probably twenty miles or have lived here all of their lives and never been here. Especially us.

Some of [guests] I’ve seen them year after year since I’ve been here. Some people have been coming to here seventeen, eighteen, twenty years. Every. Year. They’ve been here that long. They’ve seen it change, you know, to this. This is like our second week in opening this, so, you know, they’ve still got a lot of kinks they’ve gotta work out, but I think it’s gonna be fine.

They are just such touchable, talkable people . . . It’s just so Southern and country. But you know, no matter where you go, it’s always some kinda racism. You get people that come here, and sometimes you can tell a little sompin’-sompin’. And that’s somethin’ you can’t hide. You might for a little bit, but eventually it’s goin’a come out. So I have already seen some stuff, but, baby, I’m here, so…Until I get ready to leave, I’ll be here! But for 95% of the people who work here, I love them, and they’re great to me, and never have I had a cross word or anything…not to my face!

. . . Clent? Did you pick up somethin’? Mhm—yeah. This is what I’m gonna say: I kinda feel like there is some . . . But he likes me. Sometimes, white people like lighter-skinned people, so I don’t know if it’s that. We had a dark-skinned Haitian girl and they treated her like crap. I was embarrassed my own self! I feel like it’s down in Clent because it’s that age and the era that he came from—I’ve always sensed that—but he’s never said a cross word to me, and he comes in here almost everyday to speak to me. I don’t know why.

Elaine & Bill, Guests

Elaine and Bill were the only other black guests on the property. They overheard my interview with Clent and were thrilled to discover that I attended their daughter’s alma mater. The couple was exceptionally merry, sprinkling every moment with a hearty laugh. Elaine discretely told my mother how racially isolated she felt at the resort, but once I hit “record,” she and her husband spoke less freely.

Elaine: Our daughter—our only child—recently got married on December 2, 2018, and this—

Bill: 17.

Elaine: 2017—I’m sorry. And this is a thank you gift from her and her husband. We’ve gone to many resorts in North Georgia, and I must admit I was a little apprehensive, because we’ve booked some—that are even through agencies—that said, “Oh, this is great!” We got there, and it was a flop! But I just trusted the Lord this time, cause I know my daughter’s taste. So…didn’t know what to expect, really. Did you?

Bill: I thank you for the opportunity to speak! We were really just lookin’ for a time of peace and tranquility, get away, time with each other, time to do some reading . . . So as long as it’s out and away from the rat race, we pretty much knew we could enjoy ourselves.

Elaine: I personally enjoy it. I am impressed with the quality, the classiness. The hospitality has been impeccable, especially the service—beyond what I’ve ever experienced, to be honest with you. And I just think it’s just a beautiful, tranquil place to come.

Bill: And with me, this Barnsley restoration is like an added addition. I have an interest in history, trees, outdoors—

Elaine: Civil War.

Bill:—able to see some of the Civil War. And the people who served here. So this is just an added addition and something that we really didn’t expect but we really enjoy.

Elaine: It has changed somewhat. I didn’t know the history of it. We did know that the young man—the first owner—came from England. I asked the bellman, “Well, how did this come to be?” And he gave us the story of the English European guy. And so quite naturally, my finite mind jumped to slavery. Now, realizing from just this tour, [the founder] did not believe in slavery. And his wife was from a rich family in Savannah that had slaves, four of them. But when they came here, he said, “No—I don’t want any slaves. They’re now servants.” So he treated them as such. They read, he treated them with—what did [Clent] say? He taught ’em to read—

Bill: They were not allowed to have kids until they were married.

Elaine: They were not allowed to have children until they were married—so I think the moral of this, it really enriched my visit. That this was not a slave house—slave ranch—establishment as I thought.

Clent

I’d like ’em to enjoy the story, but also to see an original old landscape. It was established here back in the Indian times, and now we’ve got new amenities on the property to enjoy. Our new hotel, Georgian Hall, village over there, course the golf course, the shooting clays, fly fishing, kayaking and all kinds of things. And of course we have the little family and children’s petting zoo. The director there, she has horseback riding and lots of things. And now Mr. Jarvis, our general manager, is working to add even more.

Nancy

There’s a lot of activities you can do: They have the horseback riding, they have the clays course, then they have the sportin’ club you can go and shoot—it just depends on if you like to shoot quail or a duck . . . Then they have bicycle rentals, you can fish, there’s canoes . . . We even have checkerboards over at the outpost that you can sit outside and play! It’s limitless what you can do out here: hiking trails, just a lot of different stuff.

Sheila

Everything around here is pricey. Earlier this week, a couple came in wanting to go horseback riding and they said it was $65 per person.

They offer horseback riding, they offer skeet shooting, they offer paintball, they have a petting farm for small kids, they have golf, they have clay shooting . . . Everything basically is outdoors. And we’re not necessarily always outdoor people—Oh, you don’t have to put that in there! But seriously—when black people come, they’re like, “Is there anything here to do that isn’t outdoors?” And they have lots of different trails you can go walk and stuff like that. But if you don’t like outdoors, Barnsley is not the place to come.

Oh, another thing: We do movie nights . . . they put a big screen in the middle of the village and everybody can just come out and watch a movie. They had a movie night, like—you probably won’t know nothin’ about this—but you remember when we used to go to the drive-in? Well they did that on the golf course last year, and you drove your golf carts, and they watched the movie. So just different things that they can think of and do, and especially in the summertime, when there’s lots of kids. And then they’re doin’ lots of camps. Some of the recreation departments around here would bring their kids for just a day camp.

Clent

We do big corporate events here. Course we have families, and we do a lot of weddings. We had sixty weddings here last year. And the girls have got a lot more booked this year. My great-grandparents had their wedding out in the front gardens here in 1882. It’s a natural for weddings.

Nancy

There’s a lot of weddings. Very popular for weddings. Very popular. People actually get married out next to the green. Like the golf course. And then the ruins, of course. We also have a chapel, and now we have the Georgian Hall. So there’s so many choices. I think it’s social media. Everyone posts pictures nowadays. And so people see those pictures and they’re just like, “I can’t turn that down. I would definitely wanna take pictures there and have my own wedding there, cause it’s so pretty!”

Sheila

There’s a wedding on property today. They go from anywhere to 25 to 350, but now we just built the Georgian Hall down there—I don’t know if you’ve seen that big building—that just opened, so we can do probably 500 to 1,000 ‘cause it’s that big on the inside. So, literally from March to November, there’s usually a wedding here every weekend. Sometimes Friday, Saturday, and Sunday. That’s the main event that we do.

Oh god, the weddings are beautiful! Like, before we moved here, we were in the circle green building and the boutique was in there. So I could just walk out the back side to the village and see the bride go into the church, and all the pictures. And somebody asked me, “What are you gonna miss?” And I said, “Everything that happens in the village—I won’t be able to see it!”

The wedding this weekend—the mother, a salesperson, works out of her home in Atlanta, but she brings business to Barnsley. She’s been here for a long time, so her daughter’s getting married here. Before, I guess you heard Clint say that Prince Fugger owned this. He came over just for this wedding this weekend!

Anthony

I think that if they want to get married there, it’s fine. It’s probably a place that I wouldn’t necessarily choose, but as long as they’re not discriminating against others, I guess I’m okay with it. They own the property—they can do what they want. Because any place, especially in the South, is gonna have history.

Denise

To be frank: I didn’t know that people would actually want to be married on a plantation unless they were two white people, but I’m sure that’s not the case—it could probably be anybody. It kind of saddens me. When I think of the word “plantation,” I feel that this is a stigmatism of superiority of one group of people over another group of people. So for someone to feel that that type of place that they want to celebrate an event such as a wedding—I feel that it is kind of demeaning. I would not attend if I was invited to a wedding—and don’t you get married at no plantation!

Larry

I don’t like ’em. I hope my niece don’t go through a—I don’t like ‘em, Linseigh! I can’t stand ‘em! It hurts, just to be honest with you. The word “plantation” hurts and what our people went through . . . Some people have that mindset where it might be more appealing to them to look upon that stage. You know, they don’t have anything against it, but they want you to think you can look at them and say, “If they don’t have nothin’ against it, you should have nothin’ against it.”

Robin

I think that a lot of the whites that are excited about seeing a plantation are just ambivalent to the way that plantations were. But then there are some that would love to have those good old days back.

On the other hand, I think since it really hasn’t been that long since we had been enslaved, there’s a lot of curiosity on the parts of blacks to see, “Is that where my relatives once lived? Is that how they lived?” Our slave ancestors have only been freed for so many years. 1800s, we were slaves. And we’re living in the 21st century right now. So what is that—about 200 years ago?

As a matter of fact, Larry Shephard goes whenever he can to find a plantation. He goes because he wants to know. He wants to know history–black history. He wants to feel what it must have been like for slaves for himself. He wants to see it for himself. And he unwraps all that prettiness that is covering—or trying to cover—slavery. He unravels all that, and he sees it for himself.

Anthony

When I go there, I’m interested in the history of that site. If you choose to do golf, if they wanna hold yoga classes in the house or whatever, I guess that’s up to them. It isn’t necessarily offending in any way. I think that people look past the fact that it was a plantation; I think that they just want to stay there and have a good time.

Denise

I personally don’t like the terminology “plantation as a resort area.” And I steer away from those type places. Even though I know that there are some quote-unquote “plantations” that are really nice resorts for anybody, regardless of your race. But to me, it’s a stigmatism of white supremacy. That they’re superior over another group of people, whether it be the African Americans, or Indians, or Hispanics, not just feel that—it’s a place of showing the superiority of the white man.

Arnett, My Uncle

It’s a known thing that when people first settled here, all the large plantations, the big farms and stuff, were practically ran by the slavery industry. In the South, they can’t deny it. And I’ve never heard anyone try to deny it. What Donald Trump always say, those are—what kind of facts he call them? I could not accept anyone telling me that. If they told me, there’d be nothing I could do about it, but I couldn’t accept it. I know better. It would make me feel like somebody’s trying to change history. Trying to deny what actually happened in order to cover up somethin’. It’s a historical thing, now, like some of these Confederate monuments. It’s like something that people go to see to see how it was at one time. You know, the people that grew up in the urban areas never saw a big plot of land except in the park—where people actually lived and worked and played on the same plot of property.

The key is the way we choose to remember history. Now, there’s nothin’ wrong with plantation tourism, if the facts of actual history are there. And it’s only for posterity to know what actually happened. Tourism is not bad. If they tell the truth. And it’s still hard to find a truth these days.