The art industry is currently controlled and manipulated by the modern day “dandy” and their hunger for conspicuous consumption.

The Rebirth of the Dandy as Art Collector

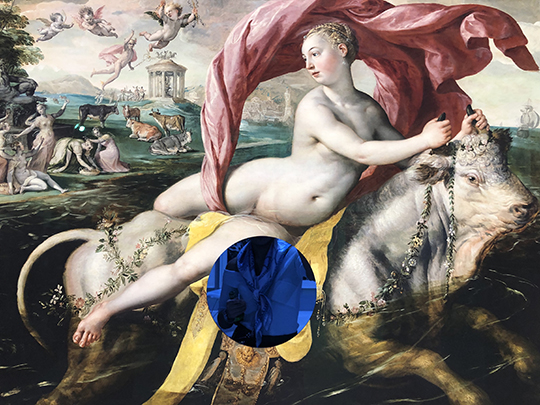

The “dandy,” an individual in old English society who portrayed his inherent superiority through his clothing, has reincarnated as the art collector, who expresses his wealth through his desire to purchase artistic works as “investments.”1 As Christian Viveros-Faune states in his essay “How Uptown Money Kills Downtown Art, “art has turned into a plaything for the 1 percent,”2 wherein the very wealthy purchase “highly valued” works for enormous sums of money, and hope to re-sell it for even more. As a result, art is no longer valued based upon its aesthetic or imaginative qualities, but rather on how expensive it is. As Sotheby’s auctioneer Tobias Meyer stated, “the best art is the most expensive because the art market is so smart.”3 But is the art market truly smart? Or do the lucky few who participate in it simply reaffirm that view in order to defend their desire for conspicuous consumption? Through purchasing works, whether from the auction house or the art fair, the collector’s motives are seemingly rooted in the desire to obtain more money than they already possess, while simultaneously showing off their ability to spend money almost wastefully. This therefore contributes to the artist’s overwhelming and constant pressure to produce commercial work, and the galleries’ equal pressure to sell commercial work. Because of this skewed system, it is no longer the critic, curator or artist who has the ability to mark works with both artistic and financial value, but instead it is the rich who have monopolized this realm, and stolen this role. The contemporary art market and collector have virtually corrupted art and its value by making it a form of currency and symbol of status within society.

The term collect, or “to gather an accumulation of (objects) especially as a hobby,”4 has been assigned a new meaning in the art world, one which is buying to sell, and which, as Viveros-Faune observes, has virtually “nothing to do with any of the issues that are central to the creation and appreciation of art in our time.”5 Expensive art has become a readily recognizable form of conspicuous consumption, one which is not only a signifier of taste and cultural awareness, but also a blatant display of monetary wealth. In particular, the auction house has contributed greatly to this phenomenon, making the purchasing and selling of art a game for contenders to pay and play. Writing in the New York Times in 2013, Roberta Smith rightly lamented, “Auctions have become the leading indicator of ultra-conspicuous consumption, pieces of public, male-dominated theater in which collectors, art dealers and auction houses flex their monetary clout, mostly for one another.”6 In this game, the contenders use the art object as a medium to express their wealth and status, utilizing it as an honorific form, one that acts as a trophy for their game well played. The dynamic animates the relationship between commodity and status that Thorstein Veblen discussed at the turn of the twentieth century: “Since the consumption of these more excellent goods is an evidence of wealth, it becomes honorific; and conversely, the failure to consume in due quantity and quality becomes a mark of inferiority and demerit.”[7. Thorstein Veblen, Theory of the Leisure Class (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1973), 46.] Therefore, the players play to win, as they desire to feed their egos with the much-needed nutrition that comes from the honorific stamp included with the purchase of a “highly-valued” work.

But how is a work deemed to be of “high-value?” It is seemingly the market itself which renders certain works to be of value, and others to simply not. “Name-brand” artists create the most “valuable work” because recognition allows for buyers to feel smart. In short, because they are somewhat familiarized with the name, works, as a result, become readily marked with a high form of value. Buyers are also aware that if they are familiarized with an artist’s name, others will be too. Therefore, as artist and critic Hito Steyerl asserts, “value arises from gossip-cum-spin and insider information.”7 Value is created in this ever-so-constructed world of “decadent, rootless, out-of touch, cosmopolitan urban elite activity.”8 The original forms of artistic value: creativity, skill, labor and meaning, are therefore to an extent lost. Although the newly marked “valued” works may also include these features, they seem to be subsumed by the overwhelming significance of the artist’s name. It is the name, which also signifies monetary value, that designates an artwork’s worth.

But the art market is not only affecting those who are willing and able to participate in it, it is, as art critic Holland Cotter has suggested, “shaping every aspect of art in the city: not just how artists live, but also what kind of art is made, and how art is presented in the media and in museums.”9 Because the art market revolves around this game, and the money involved in it, artists, galleries, museums and the media often decide what art to create, showcase, and attach value to based upon what they think will sell. As expensive art has become this form of wasteful expenditure, it has turned into something akin to luxury shopping, in which individuals buy products to display their wealth. Just as clothing was an indicator of wealth and social status for the dandy, art has become that for the collector. In Cotter’s words,

The narrowing of the market has been successful in attracting a wave of neophyte buyers who have made art shopping chic. It has also produced an epidemic of copycat collecting. To judge by the amounts of money piled up on a tiny handful of reputations, few of these collectors have the guts, or the eye or the interest, to venture far from blue-chip boilerplate. They let galleries, art advisers and the media do the choosing, and the media doesn’t particularly include art critics.10

One can begin to compare artworks from recognized artists to designer brands. It is society, specifically the media, who has the power to mark certain brands as valuable, or as indicators of wealth that can be easily identified by society. This also contributes to this idea that the true value of art has become virtually unrecognizable, as the majority of artworks that top galleries choose to represent communicate no clear or coherent formal values. The works are instead united in their high price tags. The message is therefore that collectors do not care about the aesthetics of artworks themselves, but merely their monetized worth.

In particular, art fairs have become the epitome of the ultimate high-end department store for collectors, a space where the purchase of designer art objects is accessible, and most importantly, a space where other collectors can witness these purchases. Don Thompson describes the opulence of one of the most popular fairs:

Art Basel Miami Beach, known to all who attend as “Miami Basel,” is the most spectacular art fair in the world, the prime example of how the relationship between art and money has simultaneously become glamorous and intellectually numbing. Miami Basel is a combination of art viewing, celebrity spotting, beach parties, sipping a $20 glass of Ruinart Champagne served from coffee carts, and other forms of really conspicuous consumption.11

Miami Basel publicly distinguishes the people there for a shopping spree from the people there to window shop by designating particular days for particular audiences, thereby creating a strict hierarchical ladder for the week of the year it exists. But Miami Basel is the ultimate shopping experience for those with money, because it’s like a sample sale minus the sale part. In Thompson’s words, “At Miami Basel, dealers with trophy works fronting their booth compile a list of interested collectors to whom they have offered holds. The winner is the collector whose personal brand will bestow the most prestige on the artist and the gallery.”12 Therefore, the game begins again, creating this competitive atmosphere among collectors to win. But why is there such an allure if winning only results in being given permission to purchase a piece? Again, an element of honor and status is linked to the ability to make this purchase. The buyer therefore obtains a sense of pride akin to being able to purchase an Hermés Birkin bag. Once again, Veblen’s ideas are brought to life:

These objects would scarcely have been coveted as they are, or have become monopolised objects of pride to their possessors and users. But the utility of these things to the possessor is commonly due less to their intrinsic beauty than to the honour which their possession and consumption confers, or to the obloquy which it wards off.13 Purchasing a Birkin bag from Hermés, as opposed to from a resale platform, can truly only be differentiated through this element of honor that comes with this permission of purchase Likewise, this same desire to obtain that which society marks as virtually unattainable can be seen in the collector at the art fair.

As workers at high-end stores often approach only those who they think will contribute to their commission, booth workers at Miami Basel pay no attention to the majority of the attendees. There is a real sense of irony here, as art is no longer at the center of the art fair. Instead, money and status have taken art’s place. Without money or “art-world clout,” individuals who are genuinely interested in the work’s themselves are completely excluded from the realm. Thompson comments on the speculative nature of collecting: “Buying contemporary art as a store of value may make sense; buying it as an investment is a beauty contest. You predict what other buyers will consider valuable in the future.”14 This is where the measure of the value of art becomes blurry; it is not the original features that matter, but once again ultimately about how these features translate into monetary value. The process becomes a form of gambling in which the collector estimates what will appear the most desirable in the future, therefore framing their purchases around this feat.

As a result of the monetarily motivated art market, society as a whole becomes confused about how the “value” of art should be determined. In particular, the art market along with museums and galleries have skewed the public’s idea of valuable art. On this topic, Holland Cotter writes,

Their job as public institutions is to change our habits of thinking and seeing. One way to do this is by bringing disparate cultures together in the same room, on the same wall, side by side. This sends two vital, accurate messages: that all these cultures are different but equally valuable; and all these cultures are also alike in essential ways, as becomes clear with exposure.15

As these public institutions often control what the majority of people believe to be significant works of art, they play a key role in exposing individuals to non-western works that are equally as significant, ones that are often ignored in the art market and in institutions. As conversations about exclusion and representation are circulating throughout multiple spheres, public institutions are becoming more aware of this issue, some are attempting to reframe the public’s idea of what constitutes value in art. MoMA, for example, will be reopening in 2019 under the guise of creating a more culturally inclusive space with an updated collection of contemporary art.16 Steps like these are crucial in framing the knowledge of the public, as the art market will certainly not be accepting new big-ticket contenders any time soon. A platform willing to expose and open the minds of the public is therefore certainly significant in reframing the idea of how art should be valued.

It is therefore this general desire to feel important, and to expresses this importance, that contributes to the construction of the “dandy” or the art collector. As writes Balzac, “Given that vanity is nothing but the art of putting on one’s Sunday best all the time, every man felt the need to have, as an example of his power, a loaded sign to inform the passerby of where he was perching on the great greasy pole, at the top of which the kings exercise their power.”17 The art collector is certainly guilty in expressing this desire to relay his wealth to society. But in addition to this ability to display his wealth, the art collector is simultaneously able to add to his wealth, in marking the art object as an investment. The media, which then acts as the liaison between the collector and the rest of society, tricks the modern man into believing that the best art is that which is most expensive. It is therefore at the hands of our modern day “dandy,” that the attributes that contribute to the valuing of art have been lost. It is now up to public institutions and the media, to reframe these ideas, so that art can gain back the priority that money has stolen from it, and society can begin to appreciate art for art and not for the price tag attached to it.

- Roland Barthes, “Dandyism and Fashion,” in The Language of Fashion, ed. Andy Stafford and Michael Carter, trans. Andy Stafford (London and New York: Bloomsbury, 2013)

- Christian Viveros-Faune, “How Uptown Money Kills Downtown Art,” The Huffington Post, February 6, 2013, www.huffingtonpost.com/2013/02/06/how-uptown-money-kills-do_n_2629740.html.

- Viveros-Faune, “How Uptown Money Kills Downtown Art.”

- “Collect,” Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/collect.

- Viveros-Faune, “How Uptown Money Kills Downtown Art.”

- Roberta Smith, “Art Is Hard to See through the Clutter of Dollar Signs,” The New York Times, October 19, 2018, www.nytimes.com/2013/11/14/arts/design/art-is-hard-to-see-through-the-clutter-of-dollar-signs.html.

- Hito Steyerl, “If You Don’t Have Bread, Eat Art!: Contemporary Art and Derivative Fascisms,” e-flux, The Truth of Art – Journal #71, March 2016, www.e-flux.com/journal/76/69732/if-you-don-t-have-bread-eat-art-contemporary-art-and-derivative-fascisms/.

- Steyerl, “If You Don’t Have Bread, Eat Art!”

- Holland Cotter, “Lost in the Gallery-Industrial Complex,” The New York Times, January 17 2014, www.nytimes.com/2014/01/19/arts/design/holland-cotter-looks-at-money-in-art.html.

- Cotter, “Lost in the Gallery-Industrial Complex.”

- Don Thompson, Supermodel and the Brillo Box (New York: St. Martins Press, 2015), 233.

- Thompson, Supermodel and the Brillo Box, 236.

- Veblen, Theory of the Leisure Class, 79.

- Thompson, Supermodel and the Brillo Box, 80.

- Cotter, “Lost in the Gallery-Industrial Complex.”

- “About: New MoMA,” MoMA, www.moma.org/about/new-moma.

- Honoré de Balzac, Treatise on Elegant Living, translated by Napoleon Jeffries (Cambridge, MA: Wakefield Press, 2010), 13.