“Silence. The flip of a thin page, like a wave.”

Circulation

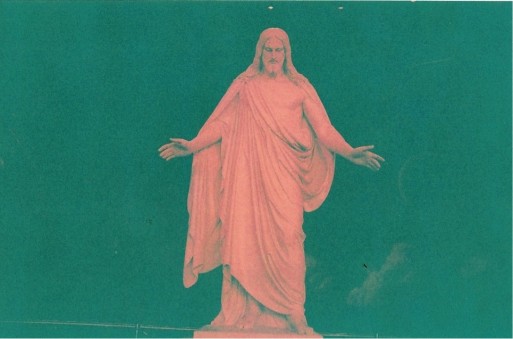

Here He is again, hair parted down the middle, a perfectly symmetrical face, robe draped over one shoulder. She remembers it all very well. Remembers how His arms rose to summon it all: her mother, stiff as a sewing needle in her buried box; her eggs, like spoiled produce; the cluster of her belongings in the trunk of her car in the driveway of her ex-husband’s house. All of it surfacing like dead fish.

She must remind herself that she is not there but here, at a desk topped with photographs in the middle of a room full of boxes, a few still unopened. She sets the photo aside and moves on. But the other pictures are of pointless things: new car, old car, new house, old house. Old new husband. Her gaze returns to Jesus. This time she notices something—a black speck near the lower-right corner. A blemish smaller than an ant. Is this what fear looks like? She did have fear, no doubt, at the feet of Jesus. His shadow fell over her like a net, and she thought, So this is what judgment feels like? She had never been religious, but she was on the lip of meltdown: motherless, babyless, and now ringless. She found herself unable to breathe, and at His feet, it only intensified. She couldn’t look at His head (those stone-cold eyes). Besides, that close, it would have given her a neck cramp. Yet she wanted to talk to Him. One on one.

His feet looked fake, prosthetic, but also pure, except for a small crack in the middle toe of His left foot. Was it hollow? Is this what the helpless saw when they fell to their knees? Feet that walked deserts, that crossed waters—hollow feet that, if tapped, sound like a knock on a coffin? She looked up. His white arms extended above her like the wings of a cormorant she had seen once as a child.

The doorbell rings. Through the window, a neighbor with a welcoming pie. One side of her collar is upturned. A baby has toyed with it, she is sure. She opens the door, and the neighbor lifts the aluminum foil. Cherry, with a lattice crust.

“My favorite! That’s so thoughtful.”

In truth, it is not her favorite. She hates cherries—especially when they are baked in pies. She does not like the look of them, like the hearts of mice, all packed together under the crosses of the lattice. Or—other times—they remind her of dried embryos: mutated, congealed.

“Just a ‘Welcome to the neighborhood’ pie. I’m Tania.”

“Olivia. It’s very nice to meet you. ”

“So, are you about moved in?”

She steps aside. Boxes. A plastic bag quivers under an air vent. “I’ll get there, eventually.” She shrugs and they laugh.

Tania shifts her feet. “Have you met my husband?”

Her face is suddenly a child’s, her eyes wide and naïve. Olivia could tell her that she is quite familiar with her husband, that she saw him two nights ago from the window in the study, that he stood idle outside his family’s front door for a good minute, having checked his collar, his shirt buttons, his belt, his shoelaces, before digging in his pocket for the key. She could tell her that her marriage will soon fizzle out like an old firework. But she won’t. She clears her throat and says, “No, I haven’t.”

“You’ll have to come over sometime.”

They both nod. Then Tania looks at her watch. “I should go. I don’t want to take up too much of your time. It was very nice to meet you.”

“Of course. It was very nice to meet you. And thank you! I expect I’ll see you around!”

The soft closing of the door. She puts the pie in the empty fridge and returns to the study to sort through more boxes. The picture lies on the desk, and as she stores scissors, pencils, a box of paper clips, she keeps glancing at it. The wings of a bird of her childhood, the bottom of His robe. She thinks about her new neighbor (Tina?), how old she might be, if she has any pets, what the inside of her house looks like. Then she can’t resist and she asks how many kids she has, what their names are. And her husband? Do her parents help with the Thanksgiving dinner? She tosses a handful of thumbtacks into a drawer and picks up the photo again.

Now she can remember the sounds. The low roll of cancer fanning out over each of her mother’s lungs. Rain on black umbrellas. The squeak of a child’s sneakers against the slide at the nearby park. The voices of doctors talking of estrogen, of genetic mutations of the ova. The pop of a balloon at a co-worker’s baby shower. Her husband’s quiet sobbing. (The church organ begins to play from behind Him.) More doctors: folliculogenesis and cryopreservation and endometriosis. The shuffling feet of the pregnant woman in Target before she stopped at a baby swing on display and pushed it back and forth. The turning of pages and adolescents’ giggles on the other side of the bookshelf. Shhh! This is a library! More doctors. It’s just not going to happen. Her husband’s fitful sleep-breathing. The whine of the hinges on the front door to the new house.

She places the photo in the top drawer.

*

A few days later she returns to work. She is a librarian, the pale face at Circulation, issuing due dates. She walks the aisles unnoticed. She listens to the silence, a cemetery at five in the morning. Sits at the front desk and reads. Sometimes opens the dictionary.

Today:

trammel.

1. A net for catching birds or fish

2. Something impeding activity, progress, or freedom: restraint

Her finger on the word, she imagines herself as the gray bird that flew into the farmer’s trammel, the gray bird in the palm of his son’s hand before dinner.

“Look what I found.”

“Throw that out and wash your hands. Dinner’s getting cold.”

And in five minutes they are around the table. Silhouettes in a window. The mother passes a plate to the son.

“Thank you, Mother.”

She looks up from the dictionary as a man drops a book in the return slot. There are times when she wonders why she is here, feels that she is caught in a different kind of net. She ages and the pages of the books yellow. She ages and the pages of the books grow yellower. But it is a better job than most. She has seen the mechanic who wipes his hands down his shirt only to find that the grime remains. She has seen the sad salesman who probably pawned his own daughter’s dress, the nurse who winces at a sneeze, the teacher with bits of crayon in her hair.

She stands, walks to the return box, and opens it. Three books, two historical narratives and a text about civil engineering. With a sigh, she picks them up and walks to the 900s. The top half of a head drifts down an adjacent aisle. Birds chirp outside, beyond the circular window at the end of the room, somewhere in the branches the big oak. She slides one of the books in its place and changes aisles for the next. She finds the row, the shelf, and then examines the book. The edges of the pages have yellowed. She flips through to check for marks in the margins, tugs to test the spine. In it goes.

For the book on civil engineering, she walks to the 600s.

624.M13. Mitchell, Karen.

Goodbye, Structural Analysis. Yellow gracefully.

Not too long ago, she was the unruly librarian in the 300s, after-hours, seated on the floor with books opened and spread around her, the crop circle of her prayers, her eggs swaying inside her. The aisle is now empty too. She walks past it, and keeps going, skin pale, lips dry, knowing the diagrams inside the covers. Aliens swimming to planets. Fetuses like sleeping bats. One book said many do somersaults. Somersaults! And then hers was somersaulting ahead, from the buried walnut in her belly to its blue-eyed emergence to the search for the lost tooth in the carpet, the smell of icing and candlewick smoke, the schoolwork scribbles, headlights scanning the walls of the bedroom at 1 a.m. on a school night, the cloudy sky over a final hug at college, the swinging strings of the graduation tassel. She stops, leans against a reference shelf, folds her arms, and unfolds them. Then she presses a hand against her lower abdomen, eyes on the floor. Silence. The flip of a thin page, like a wave.

The cormorant had bobbed up and down on a buoy. They were on the north side of the harbor, walking along a concrete dam, overlooking the ocean. The tour guide talked of how the dam had broken in the 1800s, the flooding so bad all that could be seen of some neighborhoods were the tops of chimneys. Her mother pulled her close and pointed. Out on the buoy, the bird was drying its wings. “Cor-mor-ant,” she whispered. A heavy weight: her mother’s chin pressing on the top of her head. Then the bird flew from the buoy, wings outstretched, its shadow swelling on the water and up the side of the dam, over the other tourists, and finally over her. She looked up, wanting to clutch at the bird, but it kept flying farther away, and she felt an odd estrangement, like the last night in an old home. “Fly away, birdie,” her mother whispered when the cormorant was almost to the other side of harbor.

What would she have said to Jesus, anyway? At His feet, feeling nearly as diminished as the earth when placed in the universe. And then a gaunt man had walked up and stood next to her. He looked up at His face and closed his eyes. When he opened them, he smiled, having found whatever he was looking for, apparently. After the man left, silence. Jesus waiting. She stepped back and lifted her camera. She was safe here, behind the lens. She sized Him up and clicked the shutter. Surely at this distance no one would see any cracks in Him.

When she looks up now, there’s a man at Circulation. He is tapping his foot and playing with the change in his pocket. She straightens and walks back to her place behind the desk.

His face looks tired, as if the skin, grown weary of long nights and sun and private tragedies, has loosened its hold; he must be around her age.

“I’m looking for something.”

She positions herself at the computer. “Do you have a title?”

He shakes his head. “No, but I know it’s new.”

She cracks the knuckles of her right hand under the desk. An encyclopedia of golf terms came out last week. And an autobiography of a retired jazz musician; she doesn’t remember the name.

“It was on CNN yesterday evening. Did you watch?”

No; she doesn’t watch CNN. The reporters’ voices dull her, and she hates the theme music. He fiddles with his hands.

“Well, what’s this book about?”

“Religion.”

She shifts in her chair at the computer. Two new releases on religion, but she knows exactly which one he is looking for. Not the chronicle on the rituals of an ancient Central American people called the Zapotec (she read the synopsis), but the one on modern monotheism. He’s too imploring to be looking for the chronicle, too eager. She types.

“Does Future Tense: Monotheism in the Twenty-First Century ring a bell?”

“Yes, that’s it!”

“Bellard, Lonnie,” she says under her breath. She stands. “Eight fifty-three. This way.”

He trails behind her. They walk down aisles, wind around shelves. She thinks: I am a bandleader. I am the choreographer of a fleet of dancers. They turn a corner. She thinks: I am the bird the farmer’s son nursed back to health, the bird he holds to the sky and commands, “Fly home!” The man follows more closely than others. She imagines looking down behind her to see her shadow moving over him.

She leads him down the aisle, runs a finger along the spines. “Here.” Pulls out the book.

“Thank you!” he says, taking it from her. “Great.”

“Certainly.” She nods, and watches him go.

Then she returns to Circulation. Sits. Watches bubbles float to the top of her computer screen. Waits.