“There was a tap-tapping on the heavy plank door.” A short story.

The Herbalist

It was no longer early in the morning. Light had begun to show through the stitching in the young herbalist’s curtains, illuminating its twisted pattern and washing the room in deep red. But the herbalist lay in bed, listening to the wheels and hooves, bird and marketplace chatter from the street below. There was a tap-tapping on the heavy plank door, and the herbalist knew that, despite its promise, the day was not going to be very lazy at all.

The herbalist stood into the boots that lay beside the bed and walked down the old stairs and into the parlor. It smelled strongest early in the morning, the herbalist thought. The curry, cinnamon, mushrooms, and root vegetables lay quietly in their bins throughout the night, warming and perfuming the air. It smelled strongly of the herbalist, but also of all herbalists, as if the scent were universal. Other parlors might have different notes—more peppermint or coriander, cedar or wood polish—but it was always recognizable. Though the scent had long since become home, the herbalist was still sharply aware of it. As a child, the herbalist had visited this parlor often, as though the old herbalist were a grandparent or an aging aunt or uncle. The child had guessed long before being told what honor they shared.

A young woman stood outside the door, hands plucking at the lace on her sleeves, itching maybe to retake the knocker.

“Herbalist?” she said.

“Yes.” The herbalist invited her into the parlor, fixing the curtains with rope and placing the kettle on the stove. Motioning for her to sit in an armchair, the herbalist sat across from her at the little tea table, smiling warmly to allow conversation to flow between them.

She looked at the herbalist a little inquisitively.

“You’re young. Younger than our herbalist.”

The herbalist nodded.

“You must not be much older than I am. And you look … slim.” She contemplated the herbalist for a moment, “Not male or female obviously. But maybe if you weren’t born an herbalist you would look kind of like …” she stopped herself, folding her hands neatly under her in the chair, “I’m sorry. That was rude.”

“No, it wasn’t rude. I am young. My parent herbalist was very very old, ancient.” The herbalist ran a finger pensively along a high cheekbone and soft jawline. “No herbalist had been born to this county for nearly a hundred years when I came. They were afraid god Sa’armeth had left them without a guide.”

The girl nodded distractedly, as if she knew this already. She must not have been, after all, the complete foreigner the herbalist had first thought.

The herbalist felt the silence grow and lengthen between them, could feel the girl retreating into her chair, her troubles coiling around her. She began to pick absently at her lip. The kettle whistled.

“I’m sorry,” the herbalist said, getting up, “I like history, always have, but sometimes I forget it isn’t for everyone.” The herbalist paused, scooping kava, licorice root, and orange rind into to the teapot, “But let’s start. Where are you from?”

“You know I’m not from here?”

“Well, I’m not your herbalist, am I?”

“No. We live several counties over, in the mountains, a place called Iveston. But the man, my … well, my betrothed, my husband I guess, lives here.” The herbalist nodded and sat with the pot of tea and two small round mugs. “We were married a week ago after my herbalist’s arrangement and blessing. But I don’t know him any better than he knows me. He’s a quiet man, an only child. We live with his parents. I think they had another child who died—taken by some illness I think. Sometimes at night in that house it’s so quiet I think I might break. And I’m so young.”

The herbalist looked at the girl, feeling the heat at the back of her throat, and the promise of blank days and nights ahead of her. The herbalist poured her a cup of the infusion, and pressed it gently into her hands. Her fingers stopped fidgeting as she held it between her palms.

“It’s silly to complain to you about it, you’re almost as young as I am, and you never had a choice.”

“It’s not silly at all.”

“They don’t know I’m here, of course. I left a note, but they don’t know.”

“Do they not come to see me?”

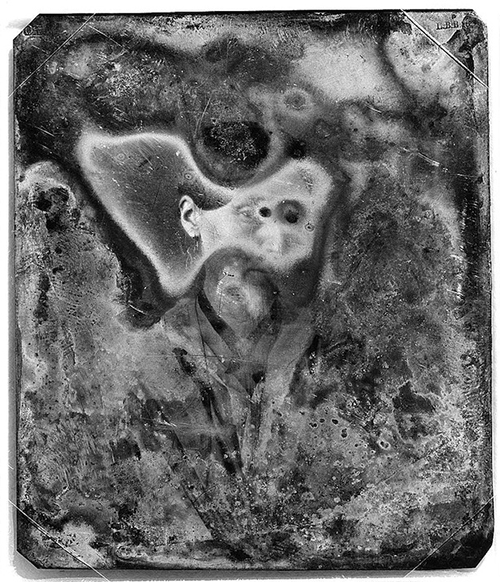

“I don’t know—I don’t think so. But it isn’t that they’re irreligious. We say the blessings to Sa’arma every morning and Sa’areth every evening. Do you know them?” She removed a small black-and-white print from her purse and handed it to the herbalist.

“The Karovs.” The herbalist’s head felt light, “Yes I know them.” The herbalists’ parents stood, twenty years older than the herbalist remembered, next to a young man with high cheekbones set in a round face. His hair was short and dark and his arms muscular. “What’s his name?”

The girl looked at the herbalist peculiarly, “Sam. Samuel. And I’m Laurie.” The herbalist looked at the print for a moment longer before handing it back to her.

“I can’t give you more choice or more opportunity, but I will do what little I can.” The herbalist went to the bins, picking out small bundles of dried plants and herbs. “These will postpone conception.” The herbalist tied the bundles together with cotton twine and attached a small note of instructions for the weekly tea. The herbalist tapped lips in thought, “I could give you something to make your husband more pliable, or gentle, or even talkative, but I wouldn’t want—” There was a tap at the door. Laurie’s eyes grew wide. The herbalist put the bundles on the counter and went to the door, searching for and then smoothing the emotion that the herbalist could feel surging behind it.

Sam stood there in the mid-afternoon, anger melting to concern on his face.

“Laurie?”

“Here,” she said from her chair. Sam calmed, looking at the herbalist gratefully, without recognition.

The herbalist invited Sam into the parlor. He kissed his wife and sat in the chair the herbalist offered, and took a cup of the kava tea. The herbalist explained to Sam why his wife had come, the contraceptives the herbalist had offered, and then sat quietly while the couple discussed what was to become of their future. Laurie touched her husband’s hand, shyly, tentatively, and he held onto it with what seemed to be an urgent and enormous love.

That night, the herbalist lay upstairs in bed. Though no great foreseer—that came with many years of the practice—the herbalist could almost see the couple’s simple future. And the herbalist liked it. The herbalist could not help but wonder what it would have been like to be born someone else, someone male or female. It was not jealousy, but a yearning to know that individual, selfish love. But somehow, before falling asleep, the herbalist felt Sa’armeth.

It was, as always, an unyielding and electric empathy, both for the herbalist, and for Samuel and Laurie, and for the herbalist’s aged parents, and everyone the herbalist would ever meet or never knew. The young herbalist felt Sa’armeth there, shuddered and sighed and fell deep, deep asleep.