I’m from white picket fences and white faces. / I’m from the stares of my neighbors. Some loving, some fake, some hostile, some come in terror.

Stranger At Home

Where I’m From

I’m from white picket fences and white faces.

I’m from the stares of my neighbors. Some loving, some fake, some hostile, some come in terror.

I’m from prayers for fairer skin to white men painted on the ceilings of churches with no purpose in going to when damned already.

I’m from paved roads with potholes.

I’m from cinder-block walls and dusty tiles. Ran miles through those halls.

I’m from big empty houses. Former spouses to a romance that faded when realized.

I’m from cul-de-sacs and driveways with highways five minutes away but nowhere to be.

I’m from YMCA and swim teams where Olympic dreams melted with the ice cream of a hot summer day.

I’m from broken daffodils and school-shooting drills.

I’m from toys traded for opioids, pills that killed friends of friends and still will.

I’m from plowed snow transformed into mansions.

I’m from manhunt matches turned memorials.

I’m from trees so green and wind so mean it leaves them barren.

I’m from mowed lawns and fresh manure. The shit stinks but looks good.

As safe as a black man can

I used to believe the city was dangerous. There were more bad things that could happen and more to be afraid of in urban settings. There were also more Black people. Now I wonder if being safe is simply synonymous with being white, because being Black I don’t think I’ve ever known how it feels to be safe. When I was younger, my friends could run around with BB guns, pelting passing cars with bullets, yet I, even as a prepubescent child, didn’t have the audacity to dream of playing with guns, fake or not. Meanwhile, my white playmates toted them freely. Ding-dong ditch always scared me, but to them, it was just a game. It’s always just a game to white people. A game that so often costs Black kids their lives. I’ve never walked around my neighborhood at night. White people fear nothing more than Black people in their spaces, especially when those Black people refuse to belittle themselves to fit into the boxes set for them. I’m afraid of how I will be feared when the sun no longer shines bright enough for my neighbors to see my familiar smile. Will they see me and my smile or the shadow of my Black body? Will they cross the street? Will they call the police? What happens then? Too many questions, too many ends. I’m afraid of the red and blue lights that stripe the backs of Black boys like me. Sometimes I think I’m overthinking. Then I think I cannot afford not to.

When I left Yardley to attend college in New York City, I felt safer than I ever had at home. As safe as a Black man can.

How We Got Here

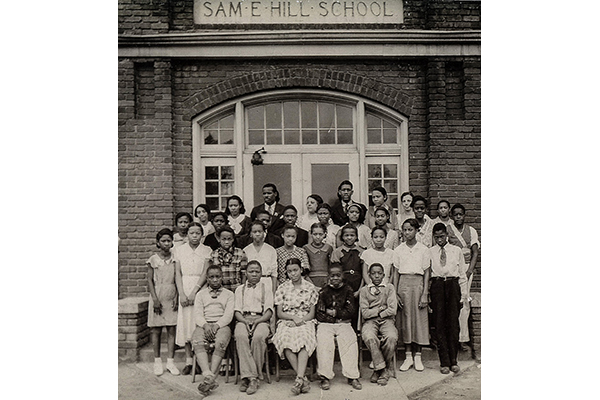

When my dad was twelve years old, his family moved from Detroit to Southfield, Michigan. At the time, Southfield was predominantly white. My grandparents joined the exodus of middle-class Black families from cities to the suburbs in 1970s.

“We moved to the suburbs because there was an increase in crime rates and there was a decrease in the quality of schools. Nanna and Granddad wanted us to have an overall better quality of life and they wanted us to be safe. So we left Detroit.”

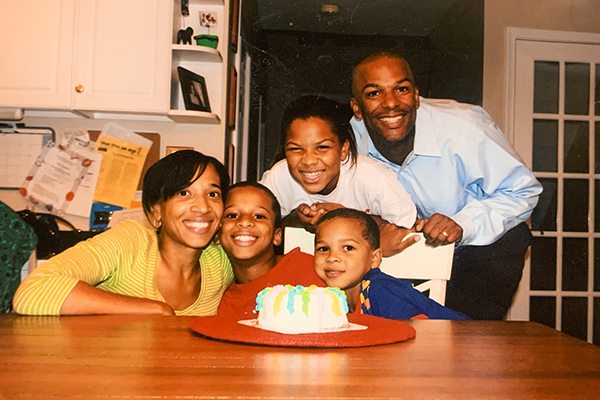

Decades later, after attending the University of Michigan and later graduate school at UCSF, where he met my mom, my dad decided to raise me and my siblings in the suburbs as well. “It was far from perfect. We wanted a mix of a diverse community on some level but also pretty good schools and Yardley and the Pennsbury school district is the best I could find.”

Like his parents before him, my mom and dad wanted a higher quality of life for their children. In many ways, Yardley has achieved that. After all, my brother and sister are both college graduates, and I currently attend one of the top universities in the United States. That said, these educational feats came at the expense of our sense of racial identity and a connection to a community that looks like and loves us.

The Name My Father Gave Me

What a song is to sing

Without a rhythm or a beat

Or a tree is to stand

Without roots

Like a man without feet

Starving eyes look to the feast

Not meant for them to eat

Backs are straightened

While the spine is missing

Ripped out of the man

Like the roots of a tree

Standing still

But barely breathing

As the voices cease to sing

The echo can be heard

Within the skin

Veins pumping

Tethered to the hearts of men

Pulling down

To hold them up

Swinging in the summer breeze

Backs bent

On their knees

Holding on

Till they cease breathe

Gasping out forgotten songs

With lyrics rewritten

To fit another a tune

Lost in the night

Lacking the light of the moon

The song is still sung

But no longer theirs to sing

They sit beneath the sun

Without a damn thing

In Shadows, I Walk

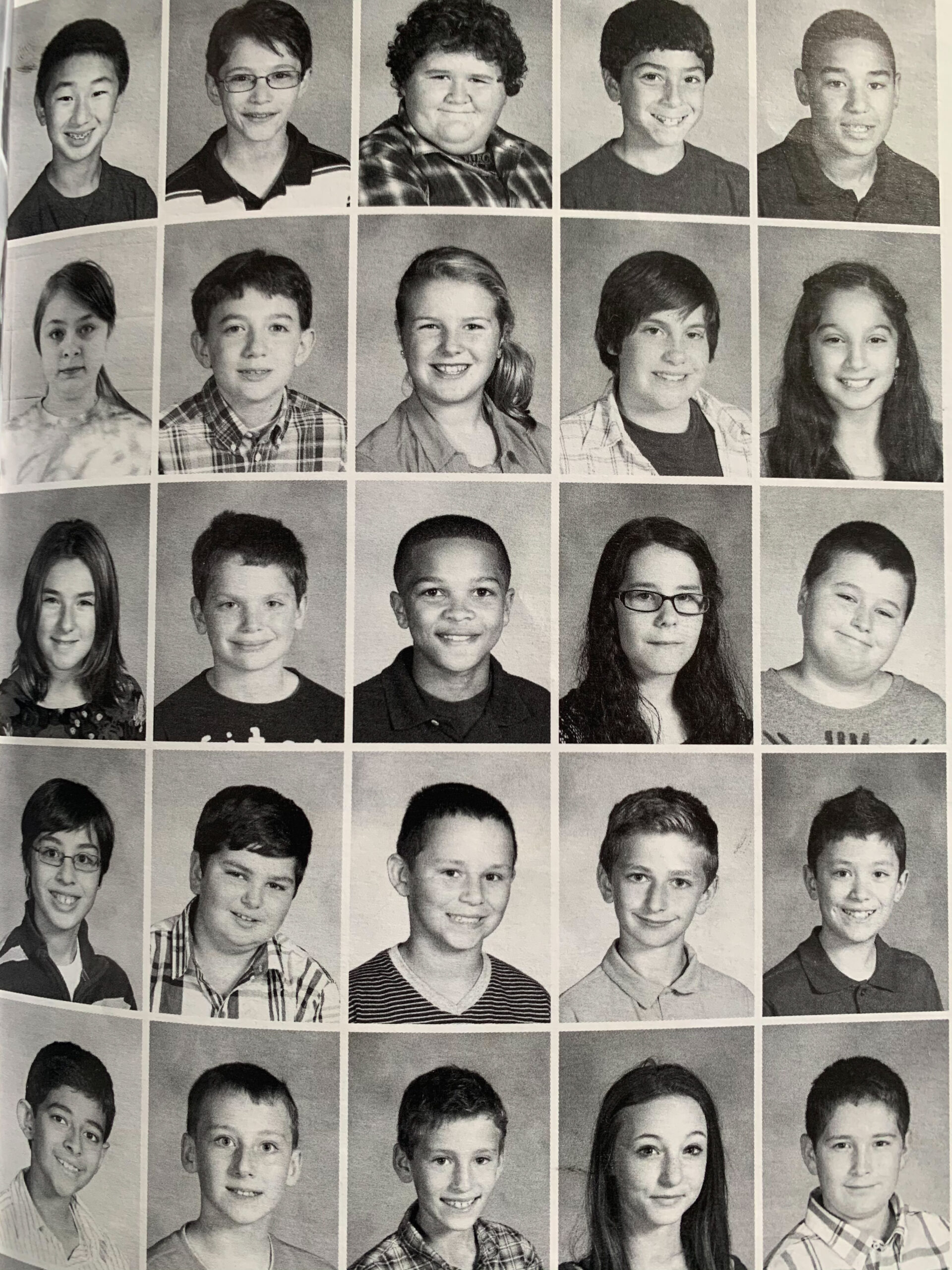

When my mom called me to let me know Mark was murdered, I thought to the last time I had spoken with him. It had been two years since we’d spent that weekend in D.C. together. We were there for a Jack and Jill event. Jack and Jill is an organization for middle-class Black youth and their mothers. I had been in Jack and Jill since my family moved to Yardley, Pennsylvania, when I was five years old. My parents wanted me and my siblings to have a connection to Black kids from similar backgrounds as us because in school and around the neighborhood, other Black kids were nowhere to be found. I met Mark through Jack and Jill. He joined when we were juniors in high school after he’d moved in with his aunt and cousins whom I’d known for years. The summer leading into our senior year, Jack and Jill held an event in D.C., where young Black people from Jack and Jill chapters all over the country came together to advocate for gun control. I remember when we met with Bob Casey, one of the U.S. Senators for Pennsylvania, and how Mark talked about kids from his old high school who’d been shot, how he talked about change. I remember how I made a joke to him about Valerie Jarrett not being Black as she addressed a crowd of hundreds of Black people. Valerie Jarret is black, but she is passing. He didn’t laugh at my joke. Instead, he told me that growing up, people always joked that he wasn’t black. He was light skinned and had red hair and talked like a white person. When he said this, I told him that it was the same for me. Growing up, I was also “the whitest Black kid.” He mentioned how he always felt the need to prove his Blackness and I thought about how I tried sagging my pants and using slang in middle school to fit in with the Black kids from apartment housing. That was the last real conversation I had with him. Two years later and he’s dead. I’m here. I often ask myself why he isn’t. Then I ask why I’m not where he is. It makes no sense as to why someone from a background like Mark’s should be involved in gang activity and dead before they reach nineteen. At the same time, it makes perfect sense to the world. No one is surprised when they see a dead Black boy’s name in the headlines and pictures on the news. No one is surprised when we lose our lives, whether it be in jail or homicide, because we see it all the time.

Mark saw what was destined before it was him. He likely never imagined the morgue, but he fell victim to the image Black boys are shown from the time they are born until the day they end up in one. To be Black, we must rap or trap until we become stats. To be black we must sag or talk in unnatural ways. We must act like our dads are absent from our lives because our eyes don’t open wide enough to see that being Black isn’t the stereotypes we’ve been presented as facts. The guise of what being black looks like is based in lies intended to weaken our pride. I rise for all those who died.

In trying to prove his Blackness, Mark lost his life and the world, a light.

I walk in Mark’s shadow. I walk in the shadow of all the Black kids I believed were gods before I realized my idols from adolescence were fallen angels trying to survive in hell’s heaven.

Biking

written May 28, 2020

I’m tired of being Black.

Not because I am ashamed or self-loathing, but because of the pain, restlessness, and uncertainty that comes with the pigmentation of my skin.

To me, being Black is like biking up a hill. Being Black is reaching the top of the hill, at least what appears to be the top, and not having the opportunity to stop pedaling and breathe, if only for a moment. There is no end to the affliction yet subtle pride one feels climbing up this hill. Pedaling, panting, and praying. Gasping for air that is gone, or was never there.

We ride on, as our counterparts fail to notice the hill we are trekking on. We think we are at the top of the hill, only to realize it wasn’t a hill we were climbing but a cliff. When we reach the top, we fall. Just to get up again, fooling ourselves to think this time will be different. We ride on. Pedaling, panting, praying this will end.

Pillars

Pushing ice until it melts

Like the boys that pushed

Until they melted with the ice they attained

Contained in the cold world created by boys like them

Now men long gone

Popsicles dissipated with their dreams

When ice cream turns to metal bars

Even in darkness

The stars are stolen from them

No Northstar to salvation

The freedom they dreamed of is melted

With their spirits

Leaving behind nothing but people who once felt it

To evaporate or freeze over

Until the marks disappear

Within days or maybe years

Mothers tears do not matter

When there is no one to see them

Fears forged from faith long forgotten

Remembered when the seeds

Grow up to be trees too rotten

To provide enough of what is needed

Saw them looking back

Sodom surrounded by pillars

When ice turns to water

What happens to them

Do they metamorphosize

Or remain men in the cement of their sins?

To be blue again

I look at the sky

Watching the sun fall

Watching what is

Becoming what was

It is beautiful to see

But sad at the same time

As the light fades away

For the stars to shine

I watch as the clouds bend

And the blueness turns pink

Then orange

Then red

Then black

To be blue again

It is beautiful to see

Still, sad at the same time

To see everything

When your world is blind