What does it mean to both recognize the atrocities of slavery while engaging with the environments in which it occurred as spaces of leisure and romance?

Plantation Vacation, Part II

In 2018, Confluence published excerpts of Plantation Vacation, an oral history project that scrutinizes plantation resorts and weddings. I decided to continue my research for my senior project in the spring of 2019, venturing beyond my home state of Georgia and visiting six additional plantations in South Carolina and Louisiana.

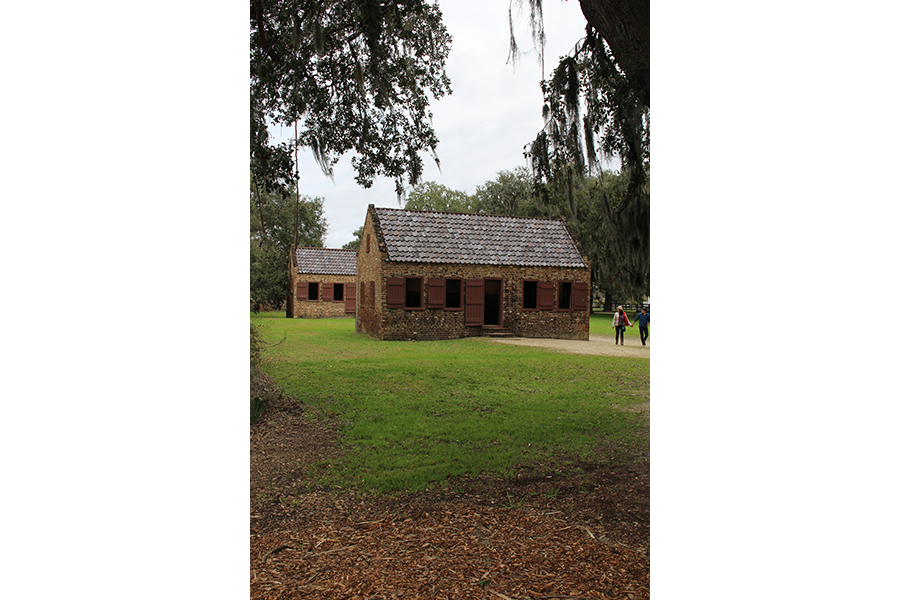

As a black person, being in such environments can often trigger inherited trauma. Many of the plantations I visited were presented as romantic—guests were often encouraged to use their imaginations to bring the past to life. Though this Gone With The Wind fantasy varied on a spectrum, the storytellers’ and visitors’ oblivion or minimization of the brutal realities of plantation life made the experience increasingly difficult. I began to realize that, generations later, black Americans are expected to maintain our patience and composure as we enter the very spaces where our ancestors suffered. We are expected to suppress our grief and rage as the oaks upon which our forefathers were lynched are adorned with Instagramable fairy lights; when the sheds where our great-great grandmothers were assaulted have been replaced by tennis courts and luxury spas. We are expected to smile and nod as we are regaled with tales about a plantation’s incarnation of Scarlett O’Hara.

By the end of this project, I found the emotional labor to be too big of an ask. What was once curiosity had boiled over into a mess of nerves, frustration, helplessness, exhaustion . . . far too many sentiments to articulate. Plantation resorts often treated big houses as the protagonists of their histories, as though the mansions were the living, breathing characters. Only once did I encounter a plantation dedicated to the enslaved: the Whitney Plantation Museum in Louisiana—the only one of its kind. The Whitney offers a narrative that swims upstream amidst flurries of hoopskirts and mansions presented as tragic heroes, the museum serves as a lone voice that reminds me of how these spaces can be preserved to respect and honor the humanity and endurance of people whose lives were devalued for the benefit of our country’s economy.

During my tour at Whitney, in which my mother and I were the only guests of color, others asked, “Where’s the fun at?” As Auntie Chae, our guide, discussed a memorial dedicated to the children who died under the conditions of slavery, some visitors shouted, “Hey—look, everybody! A snake!” They later declared said snake was “the most interesting part of the tour.” And once the tour had ended, despite Auntie Chae’s having cited every data point and anecdote, one woman muttered, “I’ll have to think about what parts I want to believe. It was all just so doom and gloom, you know?”

It was after that visit that I realized my question had evolved: Why do so many Americans have such a strong need to legitimize the “plantation myth” over evidence produced by academics and first-hand accounts? One thing was certain: I couldn’t stomach visiting another plantation.

Plantation Vacation is an attempt to catalyze the discourse that isn’t being broadly held: The desperate selective memory with which we capture the Civil War; how we go about preserving remnants of the Antebellum era; and what it means to both recognize the atrocities of slavery while engaging with the environments in which it occurred as spaces of leisure and romance. Such a conversation may involve challenging fundamental pillars of American culture and beliefs.

In the following excerpts, you will meet three tour guides: Ted, from South Carolina’s Boone Hall (immortalized as the controversial destination of Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively’s wedding); Julie and Donovan of Nottoway Plantation Resort, a sprawling estate on Louisiana’s storied River Road; and, lastly, you will meet Aunty Chae herself as she discusses Whitney Plantation Museum in all of its complexity.

Ted, Boone Hall Tour Guide

I’ve always been a little bit of a historian. Always done a lot of reading and all, and I was familiar with the plantation and with agriculture somewhat. So it came pretty easily for me. I’ve done everything out here—at one time I’ve done the house tours, Slave Street and everything.

It’s amazing what people don’t know. You know, everyone slept during history class, right? The entire slavery issue people don’t realize, and I do that maybe one day a week. And I don’t sugar coat it. I blast people out of the water. I really do. I even jump all over the Second Amendment people. And the thing that they don’t realize is that almost everybody that came to this country came because they wanted to—they were lookin’ for a better job, freedom of religion, or whatever it may be. The exception? Africans that came in chains against their will to work a short, brutal life. And people need to wrap their head around that. People don’t realize the way slavery influenced the way this country operates to this day. Like the electoral college. Slave states couldn’t count the slaves as population so they had to make sure they had the same representation. Second Amendment, they weren’t scared of England startin’ the war, comin’ back across the ocean. They kept the guns and militias because they were scared to death of revolts. I jump the Second Amendment people and I never have anybody back-talk me after that, sayin’ “but but but but…” You know, two hundred years ago, our forefathers weren’t sittin’ around in a room sayin’, “You know, we might wanna go bear huntin’ with our automatic weapons.”

You can burn the house down, I don’t think anybody would care. Stop doin’ the wagon rides, you get complaints! They’ll do a wagon ride, you know, look around at horses and all that…I don’t think they come out here for a dose of history. Once they show up, they get a good bit of it. They get a fair amount of history in the house, Slave Street has some bits of history. We try to make it as educational as possible, but I think it depends on the season. Wintertime, people come, you know, they’re really interested in the history. You don’t get a whole lot of visitors. Summertime, kids are out of school, packed, all they wanna do is take the wagon ride and then get ice cream. They’re not interested in education—you know, we can turn that backfield into a water park and they’d be thrilled to death. But then in the fall, fall is the crowd I like the most. We figure the kids are back in school, it’s safe to travel. We get a lot of bus tours, a lot of tour boats…and they’re more interested in history.

The biggest single event on the plantation was—a couple of weeks and the last Sunday of December, the Charleston Restaurant Association has a big charity of oysters out here. There were about 11,000 people out here. And a couple others: They do a Taste of Charleston out here, they do a Highlands Scottish Games…so a lot of variation of stuff out here. We probably do about sixty or seventy actual wedding ceremonies, but we’ll do well over a hundred receptions out here every year. The receptions are usually out at the Cotton Dock. And weddings are down outdoors on the front lawn or back lawn. We get very little. Most of the money goes to the vendors. You just charge to use the dirt and you have to bring in everything else: tables, chairs, music, food…we don’t do any of that. Oh, we’ve got some of the best weekends booked two years out!

Charleston’s a big wedding destination. People really have no connection here, they just wanna get married on the plantations or the historic churches or on the beach. And Ryan Reynolds and Blake Lively had their wedding here. They told everybody that was supposed to work that day not to come in. It was a secret. Nobody knew about it except their wedding planner and our wedding coordinator. Everybody got called at nine o’clock in the morning not to come in—the plantation’s closed. Oh, we found out later in the day. Saw all the pictures afterwards. But probably the biggest wedding we had out here—I’ll put it like this: the final tab for the father of the bride: $1.5 million. Of that, Boone Hall got $4,500. That was the base charge. Everything else—that whole back field was covered in tents with wood floors and a sit-down dinner for 1,500 people. Started with champagne in the garden, worked your way back, they had a parquet dance floor about as big as that parking lot area back here. Had a dance band, Josh Turner, Sister Hazel…Trisha Yearwood was a guest at the wedding, had her sing a couple of numbers before it was all over with. 1.5 million. It was one of the tobacco lawyers. Worth a whole lotta money. Daddy’s got enough money, he owns his own golf course.

We have amazing records that we keep over the years. So people don’t forget it! You have to stay abreast of it, and you know, we don’t need another subdivision and golf course over here. That’s why this is plantation—fortunately it’s historical and agricultural both, so hopefully it’s gonna stay like this.

Julie and Donovan, Nottoway Plantation Resort Tour Guides

Julie: There’s no fake news on the tour.

I don’t make up anything. We talk about the history here, it’s a difficult history.

We’re the largest antebellum home that still remains in the entire South. That’s our draw mainly. The mansion itself that you see here in front of you is the only structure that’s left from the time that this was a sugar plantation in 1859. The structure of the house is all intact. In 1980 it became a bed and breakfast and the tours began. There’s about ten tour guides. Two of us work on any given day. We have a lot of European guests, mainly French, because this was a French territory. And we do have a lot of locals, but we have people from all over the United States as well. Australia, also.

We’re a wedding destination, so we have a lot of wedding guests, bridal portraits…We also have conventions here, several bridal salons, forty hotel rooms, lounge and fitness center, tennis courts…There’s three places—no, four, actually—that you can have a banquet or rehearsal dinners: One is the White Ball Room inside the mansion. One thing that makes us different is you can actually hold events and stay overnight in the mansion. Most plantation homes have become museums, and that’s just not possible. Three of the beds in some of the hotel rooms in the mansion are original to the Randolph’s. That’s very unusual.

Tactile memory: What does it feel like—even the handrails, some of the items of the house, the low-set doorknobs, the low-set banisters–people were smaller back then–you can run your hands along there. I think it adds a tremendous amount, rather than just looking at something from a distance. Also bein’ a hotel, there’s this accessibility thing that I think some people enjoy. We do have some concerns about [the antique furniture], but the Australian owner, not being from Louisiana, said, “Don’t let the house turn into a museum.” Even though we’re a Historic Home of America and on the National Historic Register, he did want people to be able to touch and sit on some of the antiques. The fragile ones are protected. They are roped off and have “do not touch” signs. But if they’re not fragile…we have a big maintenance department. People do lament the fact that everybody is touching things…but it has to earn its keep. This mansion is 56,000 square feet, it’s larger than the White House. And it takes a huge amount of maintenance and housekeeping to clean it. So it does have to generate an income. It’s never been owned by the state.

You wanna step on in the mansion with me?

This is Donovan. He’s one of our tour guides.

Donovan: How are y’all?

Julie: After hours, [the guests] can [wander around], but the night watchman comes through every few hours and makes sure everything’s cool. Some areas are locked up at night. Like the dining room has a lot of things that could wind up in a purse. But for the most part, our overnight guests here are very considerate of the fact that they are able to do this. Now will that change in the future? Maybe. I think they encourage children to be on the back of the property in the more modern hotel rooms, because you just can’t watch everything.

People can ask any questions they want, there is nothing off the table here. We do talk about slavery here, Civil War…Some of the plantation tours do not allow you to ask questions. I think political correctness is killing some of the questions.

Donovan: A lot of people struggle with explaining and dealing with that history, especially in the current climate.

Julie: Yeah, there’s somethin’ about the Civil War or slavery in the news almost every day. This was 160 years ago. We have to talk about that every day, because it’s the truth. If you try to hide it, you’re just doomed to repeat it or sweep it under the rug. But the people that were enslaved here, they were real people. They had these experiences. And why wouldn’t you talk about that?

Donovan: Because this is a hotel, we get the opportunity to speak to people who otherwise would not have taken the initiative to go on a tour. Because they feel like it’s a discount to get a breakfast and a tour ticket, they’ll come through, and they’ll be incredibly surprised that we were able to deftly present the information as it’s supposed to be presented. It’s a good opportunity to humanize history.

People don’t like to be preached at. You know? People don’t like to be told what to do, people don’t like to be told what to think, so what we do is just provide the information, really. It creates a learning opportunity that’s disguised as a field trip, a vacation.

Julie: We try to be very, very open. The most popular questions we get are: “How do you go to the bathroom in a hoopskirt?” Yes. That’s what everybody wants to know. And, “Was John a nice slave owner?” I mean you probably don’t get the hoopskirt question!

Donovan: No.

Julie: What would you say are the most common you get?

Donovan: I mean the whole idea of, “was he a really nice slave owner,” that one was always like a dog biting at the heels.

Julie: Everybody’s relieved—I say, “Was John a good slave owner? I’m so glad you asked me that!” Because they all wanna ask it. But they’re afraid to ask. And the easy answer is “no.” Because that would explain how slavery was. But he had a reputation as a nice slave owner because he used some modern business practices to keep the slaves complacent and avoided runaways and other things that would disrupt the money making—this was a business. Every plantation is gonna be different depending on what the beliefs of the owners were. So he had this reputation—they had Sundays off here for religious services, you got married couples together with their children. But not because he was a nice guy. On the old tour in 1980, they probably said, “Oh sure, he was a nice guy!”

Auntie Chae, Whitney Plantation Museum Tour Guide

“They were treated well, they were given the best foods, and they were clothed and housed well.”

That’s not true. That’s what they wanna hear.

A lot of people choose this museum and then they get upset when they get here. It’s not my intention to upset you. You’re discontent, you’re discontent. But this is the truth, and it’s based on research. A lot of people—especially if they come from the other museums, like Oak Alley—a lot of them are based on the lives of the enslaver. So that’s really what they think happened! And because Franklin Roosevelt actually put his stamp of approval on the Federal Writer’s Project, this is not made up. Stories would’ve been lost had he not had the sense and the wherewithal to actually have those people interviewed—many of them were over a hundred years old. And they told what they experienced—you don’t have to make the stuff up. Those are some of the same stories, because all of those plantations were pretty much the same.

Now yeah, you did have some slave owners who were nicer. Some slave owners who fed their slaves better. Gave them better clothing, better housing, but at the end of the day, it doesn’t matter.

You still own the person.

Which we say is the oldest and the worst crime against nature. And that’s where people get a little more understanding.

Our groups are usually 90-100% Caucasian. When the museum first opened, our tours were mostly people from Australia and New Zealand. American whites came afterwards, and people from the UK, and then about a year and a half ago—we’ve been open four years—African American people started coming from across the country.

Empathy: That is the key. It’s something that everybody does not have while storytelling. If you’re gonna tell a specific story, you’re gonna have to know the community that story comes out of. And that’s where a lot of people make their mistakes. We have a lot of Caucasian tour guides. They do tell the story, but it’s a little bit different from the ways my story might go. And sometimes, my story is—I’m not gonna say negative—it’s a little bit more connected to what people have gone through.

Our museum is not run by African American people. The person who purchased it is a Caucasian male, 82 years old.

He had the money. He had the money. It’s about business. It’s about makin’ money. The same thing back in the time of slavery.

No disrespect to him, because I really like him. But he tells us all the time that he’s a “recovering racist.” And that kind of stumps me sometimes—kinda like, oogh! But I have to keep those two separate. Because the person he is now and the way he treats us—he’s very hands-on, a very kind person, but he’s also a businessman. I normally tell this story, because the white folks love it!

His intention was to restore everything to its former splendor and beyond. Paid eight million dollars for it. It was going to be a little home away from home where he was gonna have the golf course, swimming pool . . . In the purchase, he inherited research information. The information included a lot of those enslaved people who lived on that plantation and came back to tell their story. And because he is an attorney, he recognized a lot of those last names based on his current work. Even though their stories were profound, he initially didn’t want to use their stories, because a lot of the people in the community are related to those people. He decided to choose the other stories from people in Louisiana, but not necessarily on that plantation. All of those stories he had were very disturbing. He was upset for about a week or two, but he called a meeting with his children. They didn’t want anything to do with it, so they decided to encourage him to do a museum so that everybody would be able to come and learn. It’s transitioned to nonprofit, so it’s no longer his responsibility financially. I know about five families that live in this small community that could’ve afforded to buy this plantation and turn it into anything they wanted. They did not.

There are groups that don’t really want that museum there. Some live up right here in this community. African American people. They feel like the story’s not being told the way they learned it growing up here in Plantation Alley. People are gonna be upset on all sides of the spectrum—you’re gonna have African American people who are upset, because they want it told one way, and then you have the Caucasian people who want it told the other way, like all of the other plantation museums.

Because people get so upset, a lot of things have been removed. A few months ago we had a meeting. We can’t say “rape” anymore. Oh yeah. Really. So all I say is “sexual abuse.” Or “sexual assault”! If you’re gonna see all these light-skinned people runnin’ around on these plantations, where did they come from? You cannot put icing on it. You can’t! Even some white people feel that this thing is watered down! I’ve had people tell me, “It’s too nice! You know, you gotta tell it like it really is!”

And you know how it goes—normally, the stories are written by the victor. Not the victims. See, our people, we get angry. Really really fast. And so when we’re trying to tell the story, it comes out wrong. It’s a struggle to stay calm. It’s important, because when you start to argue with them? They argue back! They throw out things that’s untrue. It makes them feel better. It makes them feel more comfortable.

Now, the young white girl who’s running it, of course her main goal is to get to the top as quick as she can! She’s already the executive director, and she’s only about maybe 35 years old. Every time a white person gets upset about somethin’, they email us, they put it on Facebook, TripAdvisor and all those places. And then they change things up. Now they’ve started to have a training class so people can use the right words, just like politics. And then they rush you to get back in an hour and a half. I’ve had some issues with white coworkers who felt like I was going too slow. And I got hysterical, I said, “If you wanna go around, go around, but you will not push me!” Even at one point they tried to have a contest! I was like, “What are y’all sayin’ out there?” They’re not sayin’ nothin’! I say, “Kudos to you, you do what you gotta do, you make your money.” I’m gonna do my tour—they paid for it! If they ask a question, wouldn’t I be wrong to not answer? They don’t want to upset the people that have the money. And we know who has the money, right?

I don’t wanna come to work in the morning and the gates are all tied up and we can’t get in because somebody who has power was offended. That has happened many times over. So of course they’re gonna be very careful. Some people ask a lot of questions I’m not allowed to answer. Normally, if there’s some things I’m not allowed to talk about, I’ll just say, “Well you know? That’s possible, but this tour would be five hours long if we were to go into that direction.” You have to stay neutral to some degree. You have to keep it as it is meant to be: information. It’s just like the Bible. You can discuss it, interpret it how you want it . . . it just depends on what you are willing to accept.

A lot of times, they’re not engaging. I had a group of women who just kind of kept talkin’. And that’s why I kept talkin’ louder. Even though I’m the leader here, they would walk in front of me! I had to correct that as time went on. Being human myself, I get a little agitated, but I had to suppress it and be more professional. Because they will try you. All the time. I’ve had many arguments. A lot of them had to do with Irish slavery. They really believe that the Irish people were slaves, and I know it comes from Facebook. I said, “That’s propaganda.” And I don’t like bullshit. I don’t care about tips. So when they talk about Irish slavery, I just go equally hard, I’ll be like, “Oh no. Where’d you get that craziness from?” “Well yeah, they had Irish slaves, and I know!” I said, “You don’t know. There were no Irish slaves here on American soil. There were slaves in Ireland that came here as indentured servants. And they could’ve left anytime they wanted to because they were free. They were not slaves.” Sometimes, I can get very comical at times and say, “Well you know sir? It could be true. But this museum here is about the African American and the African experience. Not about the Irish. So you’re gonna have to talk about that somewhere else.”

They say when people pay their money to come in, they expect to be given a certain amount of your time. And they don’t really think about what you might be going through on a personal level. Not just the guests, but the administration. It can get emotional, physical . . . people expect you to go an extra mile. So you have to really be your own cheerleader. Some days, I just wanna go home, and I wanna just . . . be alone. Because you have to think on what you’re doing, on what you’re giving, because you are giving almost a hundred percent of yourself. But then, you have to muster up the energy to deal with the people you live with. I mean I live with my mom. My mom is almost ninety. So you have to suck it all the way an dust your shoulders off. And just keep moving. You just have to. Because other than that, you won’t be able to do it. For somebody like myself, I grew up in the neighborhood, I’m 62, I’ll be 63 in May. I’ve worked 41 years outside of the home. For me, this is my last go-round. And I have to enjoy it. So I have to take care of me. I don’t expect anybody else to do that.

Most of the people who work with me are younger. And so they are willing to conform. I remember going to a department store—I went through a “colored” door. I sat at a lunch counter. I was one of those people carrying a sign. When we were coming up, everybody’s dad worked all day long, worked hard jobs, because there were no really good jobs for African American men. They wanted you to be working in the farms, working in somebody’s bathroom, kitchen, whatever. They worked hard enough to do what they could feed their children and keep a roof over their heads. People now, they can build their half-a-million-dollar houses. They have their degrees, they have the positions. And so their children really don’t know what is known as struggle. They don’t know what it’s like to be judged just because you’re African American and you’re the smartest person in the room! When you’ve experienced those things, it’s a little bit different when you tell that story, because it gives you power. The job gives you power to make it your platform. I do go off the grid. Often. And I know they know. If they would come to me one day and say, “You have not been compliant, so we’re gonna have to let you go,” I don’t believe I would lose any sleep.

You have to be able to feel it and look at the faces of your guests. Sometimes my Caucasian guests put their heads down. I’ve had some mixed couples that come. They’re like “Whaaat?” You can see them lookin’ at each other like, “Your family, your people did this to my people.” And they pull apart! School groups—these children have gone to school since kindergarten together. Black and white. But then they look at each other like, “How come I never knew this?” That’s that disconnect that people experience. But we already know most of these people are gonna go back to that same life that they left when they decided to come to the museum. We maybe change one or two.

This thing with slavery. It’s in everything you see. I would like for somebody to explain where the hatred comes from. It’s something that’s passed on from one generation to the other because of slavery. You can flip it, you can tell it all kinds of ways, but you still have to tell it properly. Through the eyes of the enslaved people. Because they’re the ones that built the country. When we were younger, we used to watch the Tarzan movies. We never understood, because nobody ever taught us—but we would be clappin’ for the white people fighting the Africans in Africa! Then you’d see the Africans in chains. We didn’t understand that was all about slavery! And they were bringing those people here! We weren’t taught that in school. They taught you very, very little. And now they’re teaching you even less. We have to be responsible for our own history. We have to be.