To what extent does a villain become a victim? Can you make a human out of any monster?

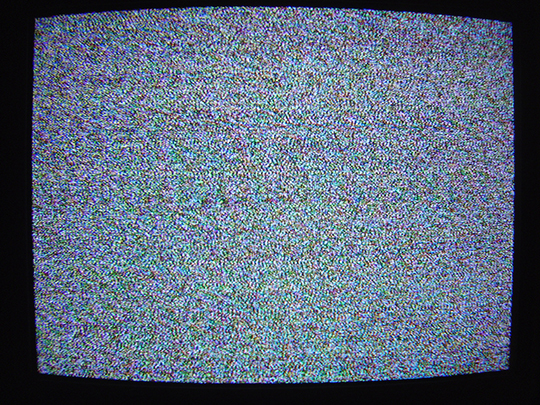

White Noise, Black Screen

Having OCD, depression, and anxiety makes it hard to express what I’m feeling occasionally. The problem is I don’t try to confine my experiences to a single word or expression predetermined in a dictionary. I say how I feel, not how I’m linguistically supposed to feel. The only accurate way I’ve been able to translate my mental state when I get depressed is by saying, “It feels as if I was watching TV loudly, and then suddenly it turned off, leaving me with the white noise of silence.”

That’s my daily life, dealing with the never-ending routine of a TV powering on and off and the questions that come with it: Who’s doing it? How do I make it stop? When will I be able to deal with the silence? Why does it seem so much louder than before? I haven’t found any of my answers yet. So, I found a temporary solution: horror films.

It may seem unhealthy for someone with depression to be so interested in scary movies. After all, one of the main arguments you’ll find any Suzan from PTA making is that “Violent TV and video games are ruining our children!” Calm down, Suzan. My interest in horror started with the beloved Saw franchise. We all know the creepy high-pitched laugh of the puppet as he came in riding on his bicycle. While most four year olds were having nightmares, I was discussing the reasoning behind the antagonist’s schemes. It’s made obvious that the mastermind behind the labyrinth of hell in which Saw takes place has a process to choose his victims and puts thought into the torture they must endure. My mother refused to let me watch such movies without her permission—which she never gave—but my dad knew where I got my interest in horror, so he always promised me that when my mom went to work, we would watch it together. I found the film much less scary than thought provoking (though I doubt I even knew what that phrase meant at the time). Rather than being motivated by evil, the antagonist acted with a moral code. The people he picked out had done wrong, and not only to him. At the time I first watch the film, I was barely a kindergartner, so it’s not like I was exactly wearing black eyeliner and singing along to My Chemical Romance. However, this is where the questions that I couldn’t ask yet but would soon be able to put into words started to form: To what extent does a villain become a victim? Can you make a human out of any monster? These complexing thoughts and the rest that formed later are what managed to distract my mind and even help understand life better as I grew older. As my mental state got worse, I started clinging to these questions desperately because I saw my own life as a type of horror movie, and I wanted answers. As long as there were new movies and new plots I could form more questions and hopefully answers. That infinite quality is something I needed. Something I could always go to—a TV that would never turn off. All I had to do was find a new movie to fill the screen.

So that’s what I did. The Hills Have Eyes (2006), Cabin in the Woods (2011), Insidious (2010), Paranormal Activity (2007), The Blair Witch Project (1999), The Others (2001), The Conjuring (2013). All of these films have probably seen the worst sides of me through the years as I’ve struggled with depression and was begging for a distraction and answers. Not only horror—occasionally I will watch a comedy or a drama to try and find someone I can relate to or aspire to be. Nonetheless, the underlying themes and messages of horror films—or, at least what I would consider a good horror film—will always hold a special place in my heart. Perhaps because it’s in those films that I find the most to relate to. The suffocating pressures and desires and desperation to be perfect in Black Swan (2010). Being made to feel crazy when the facade of someone fools others: The Orphan (2009). Needing to confront your tainted past to move forward in the present: Gerald’s Game (2017). Dealing with “It,” and realizing that you’re the one who let it in to begin with: It Comes at Night (2017). Using what others consider a disability to overcome and be stronger: Hush (2016). There was never much of a difference between what I saw on screen and what I saw in real life. I’ve witnessed monsters that are as vicious yet swift and slick as the creatures in A Quiet Place 2018). Been preyed upon by predators, such as the Moonlight Man, that attack as soon as you seem vulnerable or have lured them in with your scent—which, through my experiences, seems to be the scent of a woman, no matter how innocent. Just as many horror films do, there have been moments of comic relief and tension-free times, but the fear always comes back—whether it was because the monsters came out of hiding or because—plot twist—I was the monster all along.

Lately, my plan of distraction has backfired on me. I don’t know if my experience with the genre itself or the horrors of real life have desensitized me, but I’m left unaffected. There are a few exceptions, such as Don’t Breathe (2016), Train to Busan (2016), and pretty much anything directed by Mike Flanagan. Overall, though, horror movies are becoming too basic for me these days—too straightforward. If I think about it, the real reason is that the most frightful thing I can imagine these days is me. I’m a living psychological horror/drama, with a dash of comedy, a spoonful of parody, and a side of indie to top it all off. These other films don’t stand a chance.

I’ve heard that the reason people become unsatisfied with things (TV, film, whatever it may be) is that we start to notice the repetition of everything; the lack of originality becomes clear. Some would blame it on the times and the industry’s lack of inspiration, but it’s a trend that’s been going on for ages. It’s not the industry that changes, it’s the audience. Things we thought were so original while we were kids had already been done before to some extent in our parent’s lives, and it’s the same for our parents and their parents, all the way back to the origins of storytelling. Repeated plots, direct sequels or continuations of a franchise, it all existed before us and will continue after us.

So where does that leave me? Do I just wait, hoping there will be something original? There’s beginning to be nothing left to fill the television, forcing me to be consumed by the static on the screen. Don’t be confused—there’s a difference between the static and the silence. The static comes first when there’s a bad connection between me and a film, causing me to tune out and my thoughts to eventually get all jumbled, obnoxious, illogical, and frustrated. This usually happens when there are movies to watch, but they don’t necessarily cause me to think much beyond the film itself when I’m done watching it. Imagine Natural Born Killers (1994) with really loud emo trap music playing throughout to understand this feeling. This is very different from the feeling of a silent screen. To achieve that feeling, imagine being held against your will inside a two-by-two box, forced to watch the Japanese classic The Family Game (1983), but an even more (extra sensual) ASMR version, with the speakers right next to your ear. Uncomfortable, sensitive, claustrophobic, and tension-filled. But there’s something else added to it that I don’t know how to express except through calling it a numbness.

Do I sound hopeless? To be honest, I’ve never been a fan of happy endings, so I’m not surprised. My life seems to revolve around endings. Before I buy a book I read the last page, before I write a script I think of the last scene, and the reason I say “I love you” is that I’m thinking of a final goodbye. Instead of telling you how I think my story will end, I’ll tell you about a beginning.

Growing up, I learned to associate silence with negativity. This wasn’t intentional on the part of my parents, but I remember every time they were upset with each other they would do certain things: turn down the radio, mute the TV, and yes—pause a movie for so long, eventually, the television would go into sleep mode and turn off. You would think they did it so they could talk out their frustrations. But no, they just sat there. Each distracted by their own thoughts and with nothing to say to each other. The silence was deafening. Until things were back to normal, there would just be a neutral numb feeling throughout the house and between them. Given this context, it makes sense why the image of a turned off screen impacts me to this day.