Can meaningful change be effected from inside the system? How can public defenders break free of becoming mindless cogs?

Public Defense and Rebellious Lawyering

Working on the Inside and Outside

In the fall semester of my sophomore year in college, I completed an internship with Brooklyn Defender Services (BDS), a public criminal defense organization that offers holistic legal representation and services in Kings County, New York. As an aspiring public defender, I sought out this opportunity hoping to learn more about the work. For three months, I was an intern investigator, canvassing for video surveillance and speaking to witnesses to help gather evidence for our clients’ cases.

At first, investigation was exciting—I voyeuristically devoured the stories in the police reports, completely in awe of the overwhelming amount of private information I now had access to. My badge authorized me to stomp around the Brooklyn community, making demands for video and information under the threat of serving a subpoena. After a month of fancying myself to be a crime investigator on a TV show, I started to hate my work. I resented the blue file after blue file of investigation requests that appeared on my desk every work day. I dreaded the routine of going into business after business and home after home, only to successfully obtain video about 20 percent of the time. I begrudged the cookie-cutter emails I had to write to update attorneys on every case.

Work in the criminal justice system is plagued with banality and monotony. Former public defender James Kunen reflects:

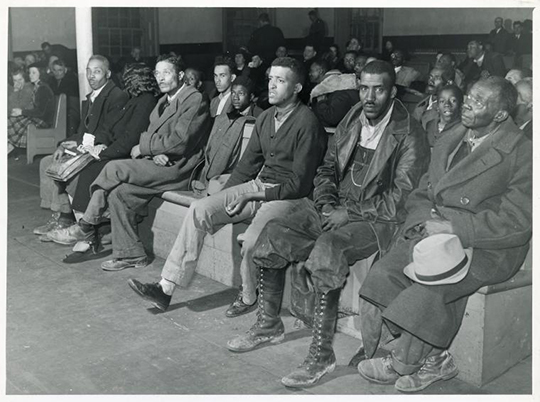

The court reminded me of a package express terminal. Each defendant was a package. The prosecutor and defense counsel were shipping clerks, who argued perfunctorily over where the package should be shipped, then accepted the determination of the black-robed dispatcher. Papers were stamped and tossed in a wire basket. The package was removed. The next package was brought in.1

Public defense is supposedly the most benevolent work in the criminal justice system. At the same time, this work, by virtue, upholds the dialectic which allows the system to exist in the first place. In this assembly-line style of “administering justice,” I had begun to feel like a steadily turning cog in the racist and discriminatory criminal justice system.

Can meaningful change be effected from inside the system? How does one work in a system that one despises? How can public defenders break free of becoming mindless cogs? In an attempt to answer these questions, I spoke to various active public defenders and read memoirs of former public defenders, academic journals on public defense work, and research center reports on community oriented defense. This paper imagines the democratic and subversive possibilities of public defense through the lens of rebellious, community-based lawyering.2

The first public defender office opened in Los Angeles County in 1914, with the goal of centralizing defense operations and making the court system more legitimate through heightened efficiency.3 Former public defender and law professor Kim Taylor-Thompson writes, “Unlike their private criminal defense counterparts, who were often criticized for engaging in aggressive tactics against the State, public defenders sought to reduce conflicts with the prosecution.”4 Taylor-Thompson goes on to explain that public defenders were thought more to function as public officials than legal representatives of individuals; adversarial public defense was deemed unnecessary because indigent defendants were presumed to be guilty.5 Hence, from the onset, public defenders were conceived as an engrained part of the criminal justice system, designed to work in conjunction with the rest of the courtroom actors.

The culture of public defense has changed greatly since its inception in the early 1900s. Now, public defense organizations often mirror private practice, where the attorneys are expected to zealously represent their individual clients. Many public defenders firmly believe in the importance of developing a personal relationship with their clients. For them, this intense focus on the individual has both intrinsic and instrumental value. A group of active and former public defenders who visited my “Race and Criminal Law” seminar repeatedly said that fostering a personal relationship was integral to humanizing and restoring dignity to clients in a system that constantly dehumanizes them.6 Another public defender from the office in Cook County agrees, “If your relationship is only about the case, then they never really have a complete relationship with you. You have to find where a person is at and learn about them a little more.”7 Federal defender and law professor Christopher Flood asserts that his effective representation is contingent on the trust between him and his client—trust that is built through “establishing a relationship from the first conversation” and showing his authentic self to initiate a “two-way humanizing process.8

A personalized approach that centers a strong client-attorney relationship is undoubtedly important. We need public defenders who deeply understand their clients and will fight tooth and nail for them in the courtroom. But what is lost through the intense fixation on the individual client in public defense? Taylor-Thompson complicates the rosy narrative of zealous representation:

Individualized approaches may provide the traditional office with options designed to promote the interests of the individual client. But when these strategies authorize defenders to pursue the interests of one client that will predictably collide with the objectives of the vast majority of clients represented by the office, the strategies may prove more harmful than not.9

For example, contesting the admissibility of evidence produced from a new technology can have radically divergent outcomes for different clients. Let’s say that the police department has started to use a new lie detection device that analyzes fluctuations in voice patterns. Mary Jane is charged with murder. The analysis of Mary Jane’s statement to the police reveals that her claims to innocence are truthful. The defense moves for the admission of the voice analysis into evidence in order to have the indictment dismissed.10 This motion to admit the evidence essentially legitimizes the technology, which poses grave problems for the public defender office’s other clients, whose voice analyses might differ from Mary Jane’s result. The legal validation of such technology limits defenders from making arguments about its possibly flawed methodology in the future, a common problem amongst lie detection mechanisms.11

I deeply understand why public defenders want the absolute best for each individual client. Lisa Salvatore is a BDS attorney that represents juveniles. She believes her role to be an on-the-ground fighter that unconditionally supports each of her clients.12 Sara Maeder is another BDS attorney whom I followed in court. Every client interview she conducted brought me to tears. I had previously done investigative work for one particular client she spoke to that day and noted in my journal:

I found out that her daughter did not want to press charges, but due to her minor status, the police and ACS could progress without her consent. The mother, crying, told me about how her daughter was cutting school all the time and getting into trouble and being verbally abusive towards her. They got into an argument that got physical which resulted in her arrest. “I just love my kids, I just don’t want things to go wrong and for her to do wrong things . . . I just want to get out of here,” she sobbed behind bars in the interview room. 13

While the vulnerable client-attorney relationship that Christopher Flood speaks of allows public defenders to enact effective individual representation, it also can blind public defenders to their potential to effect larger institutional change. Taylor-Thompson astutely observes a distinction between individual zealous representation and institutional zealous representation:

From an individualized perspective, the defender owes an obligation to represent the individual client zealously by considering only the interests of that client . . . In contrast, if the defender interprets her role from an institutional perspective, she may decide that she may still zealously represent her client if she participates in this collective strategy designed to change the prosecutors’ practice.14

It is difficult to conceive of how a public defender can maintain a productive balance between individual and institutional representation in their practice especially when considering how intensely personal the work can be. However, it’s important to remember that indigent criminal defenders have a specialized role—they are not only representing people accused of crime, they are seeking justice for an entire population that has been criminalized.

Thus, I believe that if public defenders want to prevent their work from perpetuating an unjust system, they must reflect on the definition of justice beyond the criminal court. Kunen asserts that “courts cannot reduce crime or establish justice. They are just a sorting mechanism between the front end of the system—the police—and the back end—the prison.”15 He also speaks of the myopic world of the courtroom, where the only question that matters is if the defendant is guilty of the charges.16 Indeed, even Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor once said, “justice is served when a guilty man is convicted and an innocent man is not.”17 If the public defender sees their role as merely proving the relative or absolute innocence of their client, they are upholding the false conception of justice that legitimizes the mass punishment of two million Americans. Martinis Jackson offers his conception of justice as a black man and former prosecutor: “Justice, for me, was much more than convicting a guilty person or setting an innocent one free. It was managing the balancing act of advocating for victims and protecting the community while breaking the cycle of mass incarceration and recidivism.”18 Similarly, public defender offices need to find a balance of protecting individual clients and playing a larger institutional role in order to truly defend criminalized communities.

But, what might that larger institutional role look like? Gerald Lopez’s framework of “rebellious lawyering” offers a flexible and democratic vision of lawyers’ work that can be applied to public defense.

Lopez makes a critical distinction between “regnant lawyering” and “rebellious lawyering.” Regnant lawyering, in his view, is the work that most attorneys do: formal representation and litigation from the top-down. They think that, as the experts, they are best equipped to make decisions and problem-solve.19 Regnant lawyers believe their duty is to speak on behalf of the subordinated. As early as law school, lawyers are often socialized to believe they are special oracles of knowledge due to their formidable powers of reason and debate, filtered out from highly competitive academic environments.20 Regnant lawyering prevails even amongst progressive lawyers because of the hegemonic culture of detached expertise and belligerence that dominates the legal world.21 In Lopez’s view:

This approach . . . show[s] too little interest in regularly adapting aims and means to what unfolding events and relationships reveal; too little curiosity about the institutional dynamics through which routines and habits form; too little time discovering how well strategies work for everyone affected by its reign; and too little belief in our individual and collective capacity to shape a future that does not acquiesce in the limits of today’s world.22

Rebellious lawyers, on the other hand, seek to demystify and share legal knowledge. They believe in the inherent and equal (if not superior) value of the knowledge of the community they serve. Rebellious lawyers understand that knowledge is social, an expansive web that cannot exist without lively collaboration and democratic participation.23 Indeed, as legal scholar Angelo N. Ancheta points out, “By sharing information and shifting the balance of power between lawyer and client, rebellious lawyering becomes an emancipatory activity. Power can flow between two individuals, just as it can flow between subordinated groups and social institutions.”24 Rather than viewing clients as the subject of salvation, rebellious lawyering seeks to empower and educate, where both parties of the client-attorney relationship are rejuvenated by each other’s “talent, spirit, and innovation.”25

One sparkling example of this model of rebellious lawyering can be found in the relationship between lawyers and a group of black welfare mothers in Las Vegas organizing and agitating for welfare reform in the 1960s and ’70s:

The attorneys were becoming experts in poverty law. The women were seasoned experts on poverty. Together, they translated the arcane language of the law into a language of rights and justice that they women could claim for themselves . . . Allies . . . offered intellectual, financial, and emotional resources but did not attempt to dictate either the vision or strategy of the mothers . . .” The purpose of a good ally,” Anderson liked to say, is “to be on tap, not on top.”26

Indeed, rebellious lawyers recognize the impact of collective power and strive to function as legal representatives, community educators, and community organizers.

Zealous institutional representation can be realized through the practice of rebellious lawyering amongst public defenders. Although fixation on the individual client in public defense work can be shortsighted, it’s important to recognize that effective institutional representation comes from the recognition and application of diverse subjectivities. Public defenders cannot push for institutional change without deeply understanding the community they serve. For example, the Neighborhood Defender Service of Harlem (NDS) has community boards of clients, former clients, and other community members of Harlem that the defender officer consults with prior to adopting an institutional position.27 Furthermore, NDS has an open-door policy to encourage clients to contact the office before their arraignment, which allows the office to timely investigate without relying on discovery from police.28

The Brennan Center for Justice’s Community Oriented Defender (COD) Network is another example of rebellious lawyering in public defense. A national network of one hundred defender offices, COD was founded in 2003 to engage community based institutions with defense counsel “in order to reduce unnecessary contact between individuals and the criminal justice system.”29 Their mission and principles clearly extend beyond the realm of individual representation. For example, their third commitment, “Partnering with the Community,” recognizes the two-way educational opportunity: public defense offices can educate the community about the legal work in the criminal justice system while the community can supply public defense offices with narrative and data, e.g., reports of police brutality, to help offices with case litigation.30 This relationship building can lead to vocal community support which protects defense offices against budget slashes.31

The participatory defense model is another stellar example of how public defenders can engage in rebellious lawyering through engaging and empowering directly impacted clients and their communities by involving them in defense work. This community organizing model was developed in San Jose, California, as an opportunity for people impacted by the criminal justice system to share knowledge and resources and to learn to navigate the system.32 Family members of people facing charges convene in weekly meetings to support each other and learn how to participate in the defense of their loved one, such as writing humanizing biographical narratives and dissecting police reports to find inconsistencies that public defenders can present in the courtroom.33 The participatory defense model is dynamic: It is a symbolic invitation for public defenders and the people they serve to join forces in changing an unjust system.

My limited experience as an intern investigator at BDS exposed me to a complicit, bureaucratic, and unimaginative side of public defense work that is facilitated by a myopic fixation on individual representation and lack of meaningful reflection on justice and the role of the public defender. The Community Oriented Defense Network and participatory defense, amongst many other examples, are living instances of Lopez’s model of rebellious lawyering. I do recognize, however, that some degree of perpetuation in public defense work is inevitable: as Anthony Thompson, professor of my Race and Criminal Law seminar, once told me, “You have to know a system well to burn it down.”34

Rebellious lawyering amongst public defenders is only one strand of the movement to change the criminal justice system—one movement of many in the larger liberation struggle. Regardless, radical potentialities of effecting institutional change in the criminal justice system clearly exist in the courageous collaboration between public defenders and directly impacted communities.

- James Kunen, “How Can You Defend Those People?”: The Making of a Criminal Lawyer (New York: Random House, 1983), 5.

- People pursue public defense work for a wide variety of reasons. This paper speaks to those with the intent to radically change the criminal justice system.

- Kim Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor v. Institutional Player: Alternating Visions of the Public Defender,” The Georgetown Law Journal 84 (1996): 2424.

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2424.

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2425.

- Amanda David, Christopher Flood, Vincent M. Southerland, and Len Kamdang. “Race and the Defense Function,” panel discussion at The Gallatin School of Individualized Study, New York University, New York, NY, October 30, 2018.

- Kevin Davis, Defending the Damned: Inside Chicago’s Cook County Public Defender’s Office (New York: Atria Books, 2007), 33.

- David, Flood, Southerland, and Kamdang, “Race and the Defense Function.”

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2444.

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2435.

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2437.

- Lisa Salvatore, interview by author, New York, NY, December 3, 2018.

- Judy Luo, “BDS Internship Reflection #5: Case Triage; DV Cases” (reflection, New York University Gallatin School of Individualized Study, 2018).

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2453.

- Kunen, “How Can You Defend Those People?”, 265.

- Kunen, “How Can You Defend Those People?”, 6.

- Senate Judiciary Committee, Confirmation Hearing on the Nomination of Hon. Sonia Sotomayor, to Be an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, 111th Cong., 1st sess., 2009, 149.

- Martinis M. Jackson, Justice My Way (Scotts Valley: CreateSpace, 2018), 87.

- This view is commensurate with Walter Lippman’s early conception of democracy: we need a specialized group of experts, social scientists, political leaders, and public policy analysts that support various agencies of government. Walter Lippman, Public Opinion (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and Co., 1922), 255.

- Richard L. Abel, American Lawyers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991), 223.

- Jackson, Justice My Way, 111.

- Gerald P. Lopez, “Living and Lawyering Rebelliously,” Fordham Law Review 73, no. 5 (2005): 2042-2043.

- For an account of the role of rebellious lawyering in promoting John Dewey’s vision of participatory democracy, see Ascanio Piomelli, “The Lawyer’s Role in a Contemporary Democracy, Promoting Access to Justice and Government Institutions, The Challenge of Democratic Lawyering,” Fordham Law Review 77, no. 4 (2009).

- Angelo N. Ancheta, “Community Lawyering,” California Law Review 81, no. 5 (October 1993): 30.

- Bill Ong Hing, “Coolies, James Yen, and Rebellious Advocacy,” Asian American Law Journal 14 (January 2007): 1.

- Annelise Orleck, Storming Caesars Place: How Black Mothers Fought Their Own War on Poverty (Boston: Beacon Press, 2005), 175.

- Taylor-Thompson, “Individual Actor,” 2470.

- Melanca Clark and Emily Savner, Community Oriented Defense: Stronger Public Defenders (New York: Brennan Center for Justice, 2010), 19, https://www.brennancenter.org/sites/default/files/legacy/Justice/COD%20Network/Community%20Oriented%20Defense-%20Stronger%20Public%20Defenders.pdf

- Clark and Savner, Community Oriented Defense, 3.

- Clark and Savner, Community Oriented Defense, 29.

- Clark and Savner, Community Oriented Defense, 29.

- Participatory Defense, “About Participatory Defense,” Silicon Valley De-Bug, https://www.participatorydefense.org/about.

- Raj Jayadev, “‘Participatory Defense’–Transforming the Courts through Family and Community Organizing,” The Albert Cobarrubias Justice Project, https://acjusticeproject.org/2014/10/17/participatory-defense-transforming-the-courts-through-family-and-community-organizing-by-raj-jayadev/.

- Anthony Thompson, conversation with author, November 6, 2018.