I simulated the past and present of the oyster in New York City: first eating the oyster, then destroying it, and finally recreating it.

Deconstructing and Reconstructing the Oyster

Using art to engage with New York City’s oysters

Throughout the “NYC Coastlines” class, we learned all about the coast of New York City the looming climate issues, as well as the solutions. A topic that really stuck with me was the oyster. I had absolutely no idea that oysters were a pinnacle of the New York City economy, and diet, since before the 17th century until the 1920s when oyster beds were closed because of increasingly dirty water. Through the class, I also became acquainted with the Billion Oyster Project, an organization dedicated to repopulating the New York Harbor with oysters. After talking with others, I realized I was not the only one who was in the dark about not only the history but also the present of oysters in New York City, so I decided to create an art piece that showcases the oyster. Art is one of the best ways to connect with people—everyone speaks its language, and because of this, I hope my art piece can be the beginning of many people’s understanding of the New York City oyster.

My idea was to collect oyster shells and use them to create watercolor paint that I will then use to paint an oyster shell. I wanted to do because I believe it resembles the history of the oyster. Before the 17th century well into the 19th century, oysters were enjoyed as a plentiful commodity by the Lenape and European colonizers alike, then by the mid 19th centruy began to be depleted through overharvesting and pollution, and now oyster beds are being restored. I first ate the oysters, then destroyed them and crushed them into something unrecognizable, and finally, I restored the watercolor shells into an oyster.

Oysters used to be a common food on Mannahatta, the land that New York City occupies. They were eaten by the Lenape, who showed the Dutch colonists how to eat them. In The Big Oyster, Kurlansky writes, “Indians taught the first Europeans in New York to wrap oysters in wet Seaweed and throw them on hot coals until they opened. However they managed it, processing oysters is thought to have been the earliest form of year-round mass production practiced by New Yorkers.”1 Oysters in New York were an abundant food item that was available all the time, which made them an easy target for generating profit.

In New York City, at this time, there was an extensive number of people who took up the profession of oysterman, many of whom were freed Black men. Many Black oystermen also lived in Maryland.2 However, in Maryland, “a Black oysterman, was not allowed to own his own sloop or even captain a sloop unless a white man was present.”3 While New York City was no better, abolishing slavery in 1827, in Staten Island Kurlansky writes, Black oystermen could, “work their own oyster beds.”4 In a place later named Sandy Ground, there was a community of freed Black folks, many of whom were oystermen. The oystermen, along with the whole community, prospered.

A prominent New York City oysterman and abolitionist was Thomas Downing. Kurlansky writes of him as, “one of the most respected black men in pre-Civil War New York.”5 In 1825, at 5 Broad Street, Downing opened an oyster cellar which was very well respected.6 Along with being an exceptional restaurant, Downing’s also, “served as a stop along the underground railroad.”7 Understanding the history of oysters in New York City would certainly be incomplete without recognizing Thomas Downing’s impact.

Kurlansky writes about the fact oysters in New York City were so well known that in 1857 Charles Mackay, a Scottish musician who went to New York City on tour, wrote of the experience, “‘There is no place in the world where there are such fine oysters as in New York…’”8 New York oysters were known far and wide and were shipped to many places across the world. This meant, however, that already by 1807 the oyster beds in the New York Harbor were being overfished.9 By 1820 conservation efforts for oyster beds were already underway in New Jersey after the invention of dredging, and New York followed in 1839.10

Now, when New Yorkers eat oysters, they are eating them from somewhere else. This is because of the Combined Sewer system that the City uses which pollutes the Harbor with raw sewage when there’s too much rain. As Billion Oyster Project states about the oysters, “while the Harbor flushes these pollutants quickly, oysters cannot. By filtering these pollutants as they feed, oysters remain unsafe for human consumption all of the time.” However, partially thanks to the Billion Oyster Project, the Harbor is “the cleanest it’s been in over 100 years,” because the oysters they are restoring to the Harbor are great at filtering pollutants, one of which being nitrogen. Nitrogen is very harmful, as the Billion Oyster Project states, “excessive nitrogen triggers algal blooms that deplete the water of oxygen and create “dead zones.’”11

Oysters are a foundational marine species; they do more than just filter out pollutants. Oysters also create habitats for other marine organisms. Oysters provide places for other species to live and lay their eggs.12 The oysters do so much for the New York Harbor and are necessary for fighting environmental issues. As the IPCC states in chapter 3, “Rocky shores provide services including wave attenuation, habitat provision and food resources, and these support commercial, recreational and Indigenous fisheries and shellfish aquaculture.”13 Rocky shore ecosystems are imperative to fighting climate issues. However, the organisms that live there are “highly sensitive to ocean warming, acidification and extreme heat exposure during low tide emersion” and this very much includes oysters.14 Once these foundational species start being affected by these issues, the species that live among them will lose their habitats.

It’s not just marine life that will be affected by the loss of oysters. Chapter 8 of the IPCC’s reportstates, “There is robust evidence with high agreement that future climate change impacts will have severe consequences for poor households, particularly those situated in areas highly exposed to actual or future climate hazards, such as low-lying coastal communities.”15 While waterfront properties seem desirable to those who can afford them, once an effect of climate change arises, such as flooding, they are able to move and people without those resources have to stay. This is why organizations like the Billion Oyster Project are necessary because the oysters they restore provide the wave attenuation and other aforementioned benefits that can at least slightly diminish the effects of climate change.

As I have demonstrated, Oysters do not just show up on our plates from another land; oysters have a rich past and present in New York City. I think even just generating the awareness that oysters exist in the New York Harbor is important. I hope the process and final product of my project can inspire people to learn more about the New York Harbor oyster.

After understanding the history and context of the New York City oyster more thoroughly, I began my art project by going with my friends to the Mermaid Inn in the East Village for some $1.50 happy hour oysters. I went with two friends, only one of whom joined in eating the oysters, as the other one dislikes them. We enjoyed some delicious—and cheap—oysters, as well as some other yummy—and not cheap—dishes. At the end of the meal, I admit I was pretty embarrassed to be putting the oyster shells into a bag I brought, our waiter was definitely surprised when I stopped him from clearing the shells from our table. I steeped for a bit in my embarrassment before the maître d’, Greg, came over and asked how we were doing and I told him about my project. He was interested in it and even said that the owners of the restaurant would like to see the finished product.

After acquiring the shells I went home and washed them off a bit before boiling them for a bit. I stopped boiling them, though, because I was unsure about how my roommate felt about the smell that was perfuming the air. When I took them out of the pot I washed them again. I noticed that some of the fleshy bits of the oyster that had stayed on were tender from the boiling, and they came off easily. Oddly, this removal of bits made me think more about the fact that they were once living than I did when eating them. I felt a bit mournful as I cleaned them, ridding them fully of what their shells were meant to protect.

I placed the cleaned shells in the freezer for a while; the cold prevented them from making a smell as they were being stored. When I took them out of the freezer they had some beautiful crystalline ice formations on them. I looked up online how to neutralize their scent and found several sources saying to soak them in a water bleach solution. I did this and let them sit overnight in the solution. Looking back, it’s interesting how I went to such great measures to remove their scent, to make them more palatable for me to work with. I now wonder if I should have kept their smell, which could have made for an interesting aspect of the painting.

I then scrubbed them clean with a toothbrush and some dish soap, this time to remove the bleach scent. I asked my roommate to take pictures of me doing this act, as I couldn’t take pictures myself. She was in the room as I dumped out the bleach solution and commented that it had an unpleasant smell of bleach and low tide. I put the oyster shells on paper towels on a baking sheet and placed them on my fire escape to dry in the sun.

As the shells dried, I created the watercolor medium. I found an easy recipe on a website titled “Natural Earth Paints.” They sell their own pigments and mediums ingredients, but they graciously provided a recipe for making your own medium. The recipe was very simple and the only thing I had to go out and buy was gum arabic powder, which I was able to find at a health food store near me. Then it was just mixing water, the powder, and honey together! The powder was a bit hard to dissolve into the water and took ten minutes of constant stirring to get smooth. I added some lemongrass essential oil as a preservative and put the medium in the fridge for storage.

The shells had then dried off enough, so I prepared them for crushing. I put them in a bag and then on a cutting board and sat on the floor of my room and got to whacking them with a mallet I had bought. Except, having the bag around them proved not to be the best idea, as it broke and shell pieces fell out, not to mention the irreparable damage caused to my cutting board. So I grabbed a towel and wrapped the shells in that. This helped tremendously with the mess and the noise. Although, I’m sure my downstairs neighbors were still not very happy.

I wasn’t able to crush everything into fine dust with my tools so I concocted a method of extracting the smaller particles. I placed the shell fragments into a strainer and then placed it over a bowl I didn’t use anymore. I ran water through the strainer until the bowl was almost full then I put a paper towel into the strainer, after taking the shells out, and poured the dusty water into the paper towel. The water went through the saturated paper towel but the particles didn’t. I did this twice and got a good amount of granules.

I let the shell dust dry outside for a little while before I put it into a little tinfoil bowl I made and put it in the oven to help remove moisture and make them more brittle for easier crushing. After the oven, I took the particles and put them in a cheap bowl I bought just for this purpose. Using the butt of my cat Pickle’s brush, I ground the particles as much as I could. At one point I even switched to a glass nail polish bottle, which worked pretty well. I wasn’t able to get it all to be fine dust but I tried to scoop out what I could; I definitely got some larger pieces which is quite evident in my paintings.

I then mixed the dust with the medium and made paint! After the whole process, it was really rewarding to create something that resembled what I had been wanting to create. True, there were some large particles that aren’t normally in watercolor, but I like them. They remind me, and hopefully the viewer, that there was a lot of labor that went into this, and that the paint came from the oyster.

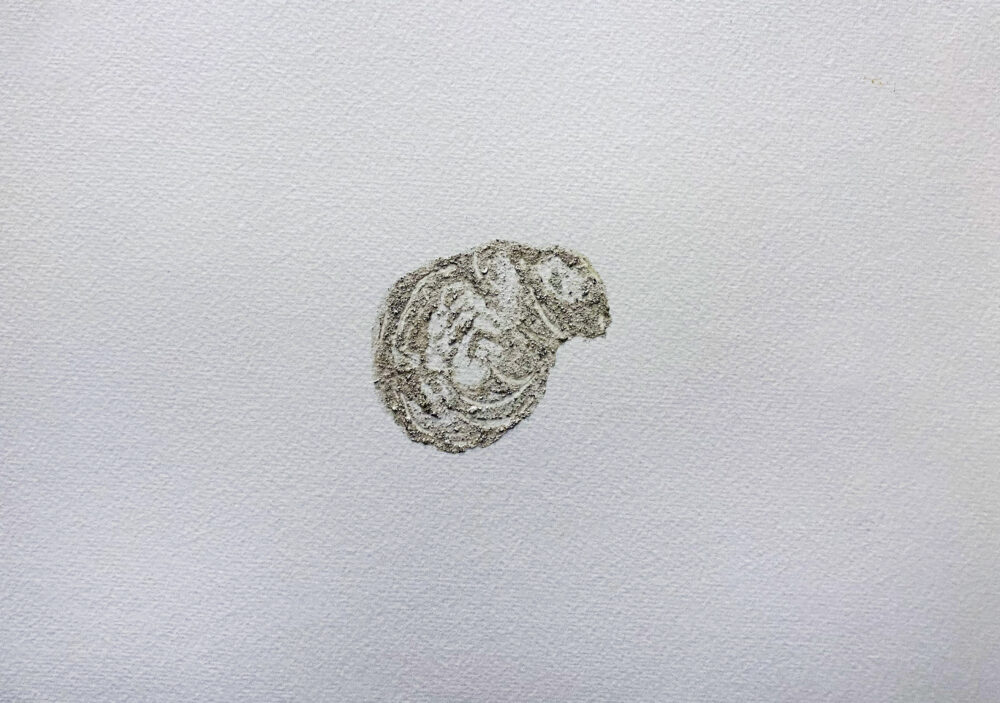

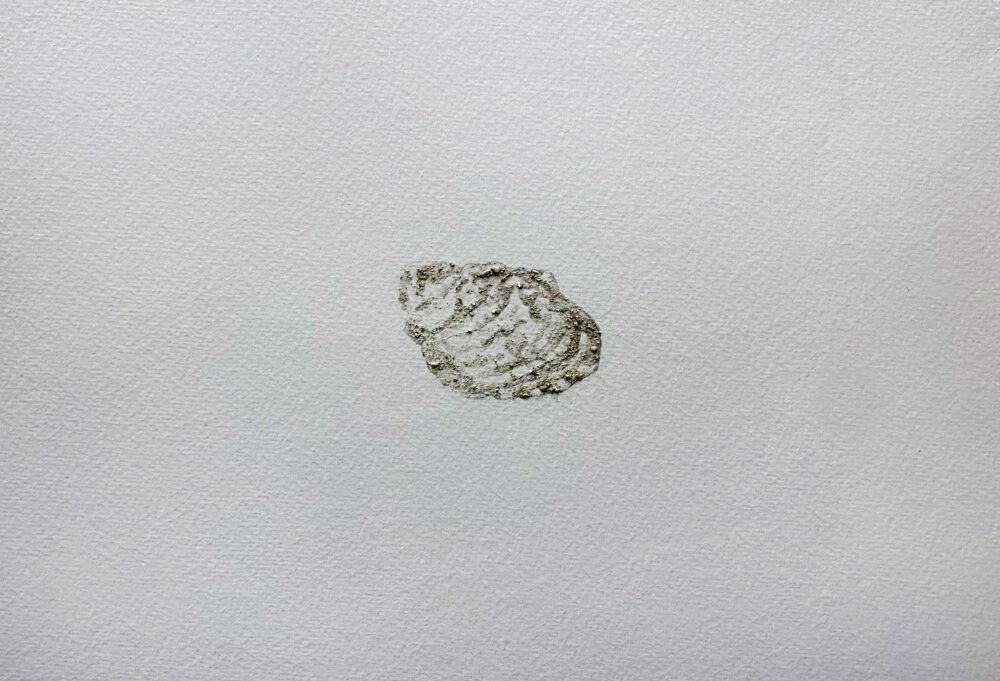

Making the first oyster painting I layered a lot and in the pictures, you can see how thick and textured it is. I didn’t have much of a technique with the first one, I think I was just excited to be painting with my homemade watercolor so I just wanted to get something on the paper. In the second iteration, I was more sparing, you can see how it’s more watery. I was trying to get more of the pigment and less of the granules because at that time I felt that it should be smoother—a notion I let go of for the last painting.

My final piece, the biggest one taking up almost the whole piece of paper, is most definitely my favorite. It lacks certain aspects I might expect out of other types of art I make like realistic depth, but I really love it. Painting with my paint was a more emotional experience than I had expected. I had thought I would be careful, not wanting to use too much, but I found that I dove in with my brush, watering it down and scraping at the granules. The feeling of the little particles moving along the textured paper felt reminiscent of stepping on a seashell-covered beach. All the different oyster shells joined together to create their final shell form and are immortalized on the page.

It may not seem that intense for a viewer who didn’t go through the process of creating the paint, but the labor it took to get that shell onto the page goes so much further than just opening a pack of paint. I do hope, though, that the viewer is moved by the painting to try and understand the history behind it. As I talked about in the beginning of this essay, oysters are incredibly important to marine ecosystems and human life; they aren’t just delicious food like I may have thought before taking this class.

- Mark Kurlansky, The Big Oyster: History on the Half Shell (Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2007), 17.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 124.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 125.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 125.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 166.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 167.

- Korsha Wilson, “The Black Oysterman Taking Half Shells from the Bar to the Block,” The New York Times, The New York Times, 21 June 2022,

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, xx.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 102.

- Kurlansky, The Big Oyster, 130-31.

- “Billion Oyster Project,” Billion Oyster Project, IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 3056 pp., doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

- M. McCann, Restoring Oysters to Urban Waters: Lessons Learned and Future Opportunities in NY/NJ Harbor, The Nature Conservancy, 2019.

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [H.-O. Pörtner et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY, USA, 414, doi:10.1017/9781009325844.

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change, 414.

- IPCC, 2022: Climate Change, 1216.