Not only does solitary confinement fail to achieve the stated goals of the practice, but many of the effects of isolating prisoners are counterproductive to addressing or preventing dangerous behavior.

Reimagining Solitary Confinement

I. Introduction

Solitary confinement is often recognized as a routine part of the United States incarceration system designed to protect inmates and staff by isolating those prisoners who exhibit dangerous behavior. However, not only are many of the goals of isolation, including the prevention of violence, not achieved through this practice, but many of the effects of isolating prisoners are counterproductive to addressing or preventing dangerous behavior. Solitary confinement has been shown to cause both temporary and permanent negative health effects on inmates and to exacerbate mental illness among those subjected to it. These negative effects have led to the questioning of the legality and morality of solitary confinement practices, which are ultimately expensive and unproductive along with being inhumane. Evidence shows that recidivism rates, mental illness, and general prison dysfunction are all associated with the use of isolated confinement. This paper addresses the negative health impacts of isolation on inmates, the questionable legality and condemnation of such practices, their counterproductive nature to stated goals, and a possible reimagining of current practices for better outcomes.

II. Background

The practice of isolating prisoners is one with a long history. One country well-known for its long-established confined isolation methods is Denmark. Pretrial or remand confinement was very common in Denmark beginning in the 1800s, with the stated purposes being to prevent the demoralization of prisoners through their interactions with each other and to avoid the possibility of collusion, witness tampering, or interference with ongoing investigations. By the 1870s, most Danish jails were equipped to isolate those in remand.1 This practice stayed legal and normalized until almost a century later, when, in 1977, human rights groups began to condemn Danish isolation practices for their lack of a maximum duration and for the negative effects that isolation could have on an inmate. By 1978, it was required by law for the police to invoke a “reason for the detention in remand,” but almost any reason given would be accepted by a judge. As such, from 1979 to 1982, an average of 43 percent of remand inmates were isolated.2 A revision to the law in 1984 maintained remand as a legal practice but required a limitation to no more than eight consecutive weeks unless the charges filed could result in six or more years of imprisonment. As a result, the percentage of remand prisoners isolated fell from 31.4 percent in 1984 to 21.5 percent by 1990.3

Meanwhile, in the United States, solitary confinement was also becoming a typical practice during the beginning of the 1800s. Prisons at first adopted the Pennsylvania model, a system in which inmates were isolated for twenty-three hours per day, but given work to do in their cells.4 By the 1830s, reports were appearing of hallucinations, dementia, and monomania in Pennsylvania-style isolated prisoners.5 By 1844, a New Jersey penitentiary physician had found that when isolated prisoners began to show signs of mental disorder, adding a cellmate could clear the exhibited symptoms, yet it was not until the early twentieth century that a full shift away from the Pennsylvania model was made.6 New York, which attempted an eighteen-month experiment of isolating prisoners with no work at all, resulting in the immediate release of twenty-six inmate “survivors,” finally shifted away from full isolation, turning to the Auburn system and allowing inmates to work together during the daytime in 19207 This system gradually became the norm, and solitary confinement became a less common practice, eliciting condemnation from the 1960s forward. At that time, research centering around sensory or perceptual deprivation and the possibility of the “brainwashing” of prisoners of war during the Korean War led to the condemnation of isolated prison sentences.8

In the 1980s, however, Marion Penitentiary became the first super-maximum security prison in the United States, reinstating the use of solitary confinement as a norm. In October of 1983, two prison guards were killed on the same day, resulting in a lockdown of the prison. The lockdown was never lifted; inmates remained confined to their cells without access to communal activities. This permanent lockdown was later dubbed with the name “supermax,” normalizing the use of solitary confinement as a tool against prisoners who behaved in dangerous ways.9 By 2006, there were at least fifty-seven supermax facilities in the United States housing upwards of twenty-thousand prisoners.10

Most researchers share a definition of solitary confinement as the isolated confinement of prisoners for twenty-three hours a day in a barren environment, often under extreme levels of surveillance. While circumstances vary in different facilities, a key feature of solitary confinement is a lack of socially and psychologically meaningful contact with other individuals.11 Visitors and phone calls are severely restricted and infrequent if allowed at all and physical contact is limited to a correctional officer restraining or removing prisoners’ restraints through the security door. Education and work programs are usually not provided.12 In 2006, an Urban Institute report found that 95 percent of prison wardens agreed with a definition of a supermax unit as having the following characteristics: “a stand-alone unit or part of another facility [that] is designated for violent or disruptive inmates”, a unit that “typically involves single-cell confinement for up to 23 hours per day for an indefinite period of time”, and a unit in which inmates “have minimal contact with staff and other inmates”13 When the terms “solitary confinement” or “supermax” are used here, they refer to these conditions of isolated confinement.

Solitary confinement can take multiple forms, often referred to together as forms of restrictive housing. Administrative segregation refers to temporary isolated confinement, usually while prison employees or administrators make decisions about where a prisoner should be housed or how a prisoner should be punished for disruptive behavior. Prisoners are sometimes punished with disciplinary segregation, a form of isolation that can be temporary or long-term that is employed in response to a perceived threat. Protective segregation can also involve the use of solitary confinement, in which case a prisoner is isolated in order to separate them from the rest of the prison population for their own safety.14

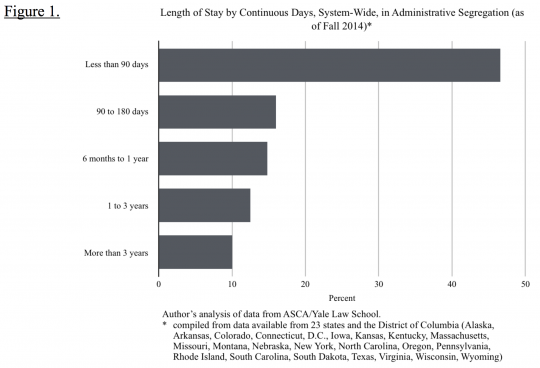

The use of all three of these kinds of solitary confinement has been normalized in prisons and jails. From 2011 to 2012, 18.1 percent of the prison population and 17.4 percent of jail inmates spent time in restrictive housing, with 10 percent and 5 percent respectively spending thirty or more days isolated.15 At any given time, an estimated 4.4 percent of state and federal inmates and 2.7 percent of jail inmates are held in administrative segregation.16 Among these isolated prisoners, a substantial number spend longer than one consecutive month at a time in isolated confinement (Figure 1). The highest percentage of prisoners, 28.9 percent, spend 1 to 3 consecutive months in isolation. As such, research regarding the effects of isolation for longer than four weeks is particularly pertinent.

III. Health Effects

Solitary confinement has been shown to have substantial effects on the mental and physical health of prison inmates. It is common for prison inmates to suffer from mental illness regardless of whether they are subjected to isolation. A study from the American Psychiatric Association in 2000 found that 20 percent of all prisoners were seriously mentally ill with 5 percent being actively psychotic at any given moment.17 A 2003 report from Human Rights Watch found that prisons themselves regularly report anywhere from 11 to 16.5 percent of offenders as mentally ill.18

While mental health disorders are somewhat common within prisons, they are particularly common among those who are isolated. A review of the literature surrounding isolated confinement makes it abundantly clear that rates of psychiatric and psychological health problems are higher in isolated prisoners than in the general prison population.19 Isolated inmates are susceptible to a number of health problems that seem to be a direct outcome of their isolation. Some of these symptoms are physical, such as severe headaches as well as pains in the abdomen or muscle pains in the neck and back. Heart palpitations or increased pulse are common, as are problems with digestion or loss of weight or appetite. Many prisoners experience lethargy, including chronic tiredness or trouble sleeping. A lack of sleep contributes to a loss of sense of time, which is a frequent symptom in isolated prisoners.20 More traditional mental symptoms also appear frequently, such as symptoms of confusion including dizziness, the inability to concentrate, difficulty communicating, and loss of memory.21 Inmates may also develop an oversensitivity to stimuli, making mundane sounds, smells, or light seem impossible to tolerate.22 When inmates spend long stretches of time (in this case, defined as more than fifteen days) in isolation, they often experience auditory or visual hallucinations. Inmates may begin to have violent or aggressive fantasies, experience paranoid thought processes, and become impulsive and emotional. A lack of impulse control and frequent violent reactions are associated with time spent in isolation.23

Although many of these symptoms rapidly subside upon the termination of isolation, it is important to note that there can also be long-lasting or even permanent effects on inmates who spend long durations in isolation.24,25 For example, inmates may exhibit continued confusion or aggression after release, the inability to socialize normally without feeling overwhelmed, and aggressive responses to normal daily social interactions.26 These long-lasting or permanent effects can damage the relationships between ex-offenders (referred to from this point on as returning citizens) and their families or prevent them from performing jobs. As a result of these ongoing symptoms, many inmates who spend a large portion of their sentence in solitary confinement later choose to isolate themselves, as interaction can elicit panic and violent responses long after leaving prison.27 While researchers are hesitant to label this kind of response as a mental illness, and thus hesitant to fully conclude that solitary confinement causes mental illness itself, most agree that it exacerbates existing mental health conditions.28

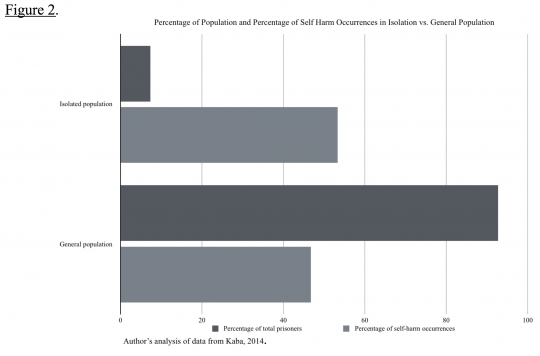

This is particularly evident in the increased risk of suicide and self-harm among isolated inmates. One 1979 study of suicides in county jails found that 68 percent of victims had been isolated at the time of their suicide, and by 1984, most experts on inmate suicide agreed that isolation greatly increased risk.29 Figure 2 shows the results of a study of the New York City jail system analyzing 244,699 incarcerations from January 1, 2010 to January 21, 2013. While inmates in isolation made up only 7.3 percent of the population, 53.3 percent of total acts of self-harm occurred among this group, demonstrating that those in isolation commit acts of self-harm at disproportionately high rates.30 The same study concluded that inmates who had ever spent time in isolation were 3.2 times as likely to commit an act of self-harm per 1000 days of incarceration as those never assigned to isolation. After controlling for length of jail stay, serious mental illness, age, and race/ethnicity, inmates punished by solitary confinement were found to be almost seven times as a likely to commit acts of self-harm.31 Inmates with pre-existing serious mental illnesses who are eighteen years old or younger account for the highest percentage of self-harm instances.32

Many of the inmates who committed acts of self-harm reported being motivated by the desire to escape isolated confinement.33 It is important to note that self-harm can actually create the opposite outcome, as it can be considered an infraction punishable with more time in isolation. As one researcher explains, “in the most extreme type of example, a patient held in solitary confinement may break off a sprinkler head, use that metal to slash themselves, and then earn not only a new infraction and more solitary confinement time, but also a new criminal charge for destruction of government property.”34 Thus, those prisoners who respond to the mental and physical tolls of solitary confinement with self-harm (whether with the intent to take their own lives or as an attempt to escape the grueling physical and mental effects of solitary) are likely to end up spending even more time in isolation and perhaps even extend their overall sentence.

IV. Isolated Demographics and Outcomes

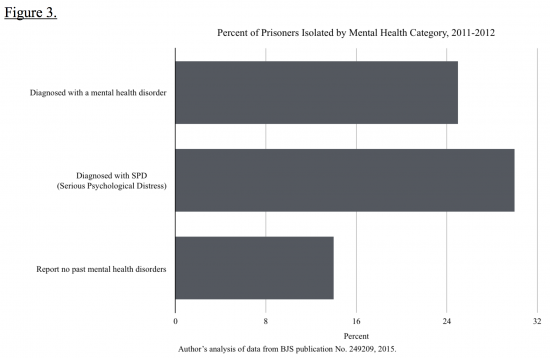

Certain populations are more likely to be represented among those in isolated confinement. First, younger offenders are more likely to spend time in isolated confinement than older offenders. While 20 percent or fewer prisoners aged thirty or older were placed in restrictive housing between 2011 and 2012, 30 percent of prisoners aged eighteen to nineteen years old were placed in isolation in the same year (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015). Mentally ill prisoners are also more likely to spend time in solitary confinement (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015). Figure 3 shows that inmates who have been diagnosed with a mental health disorder are isolated 26 percent of the time, or 30 percent of the time if the disorder fell under the category of serious psychological distress (SPD). Comparatively, 14 percent of prisoners who reported no past mental health problems spent time in isolation (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2015). Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) prisoners are also more likely to be placed in restrictive housing, with 30 percent of LGB prisoners spending time in isolation between 2011 and 2012 as compared to 19 percent of heterosexual prisoners.35

Finally, prisoners who have committed infractions of some kind are likely to spend time in isolated confinement as a form of disciplinary segregation. For example, infractions for which three quarters or more of guilty offenses result in solitary confinement include the murder of another inmate or a guard, engaging in sexual acts, possessing a dangerous weapon, or assaulting with serious injury. For fighting, threatening bodily harm, or setting a fire, more than half of guilty offenses result in isolation. Finally, for about one-third of guilty offenses, tattooing or self-mutilation, smoking in an unauthorized area, or destroying property worth more than one hundred dollars results in isolation.36 It is worth noting the breadth of offenses that can lead to disciplinary segregation; while some are overtly dangerous acts, others could be self-harm, minor rule infractions, or consensual sexual behavior (a reason that might be the cause of the higher rates of LGB people in isolation). It is not necessarily the case that every person in isolated confinement truly presents a danger to the safety of other inmates or staff. Even if one is to argue that the most dangerous of offenses should warrant isolated confinement, it is clear that this practice, which results in extremely negative mental and physical health outcomes, is not used solely in those cases.

In particular, when considering that the highest percentage of self-harm that occurs in isolation is accounted for by inmates with pre-existing serious mental illnesses who are eighteen years old or younger, it is startling to learn that mentally ill and young inmates are more likely to be isolated. These groups are the most susceptible to the negative effects of isolation. While it is possible that young, mentally ill offenders are more likely to be placed into solitary confinement because they are more likely to commit infractions for which solitary confinement is a typical punishment, it is also important to question whether isolation is an effective way to reduce the occurrence of similar incidents in the future. Even if it is indeed true that mentally ill prisoners exhibit more dangerous behaviors, there exists strong empirical evidence that solitary confinement exacerbates mental illness, in which case the solitary confinement of mentally ill prisoners is likely to exacerbate the problem of violent and dangerous behavior in the prison.

In fact, this does seem the be the case. The use of restrictive housing in prisons has been found to be associated with indicators of facility disorder, including disorder that results from violent prisoner behavior.37 Inmate interviews reveal that correlations exist between the use of restricted housing and fights between inmates, fights between inmates and staff, inmate fear of being assaulted by other inmates, inmate possession of weapons, gang activity, and theft of possessions by other inmates. A correlation also exists between the use of restricted housing and inmates’ perception that the prison lacks sufficient staff to ensure the safety and security of inmates.38

It is possible that these correlations exist not because the use of restrictive housing causes disorder but because restrictive housing is more likely to be utilized in prisons that already experience high levels of disorder as an attempt to reign in the chaos. However, even if this were the case, no data exists to suggest that implementing restrictive housing does, over time, decrease rates of facility disorder. Although it seems plausible that the use of restrictive housing has a negative effect on prison functionality through the exacerbation of mental illness and lasting symptoms of isolation, making for more violent prisoners and more facility disorder, it is not possible to empirically conclude the truth of this hypothesis. It is, however, possible to conclude that the use of restrictive housing does not seem to increase prison safety or diminish the threat posed by dangerous prisoners. Even if there is not sufficient evidence to conclude that restrictive housing has negative contributions to safety problems, it is clear that it is not a sufficient solution for solving them.

V. Legality and Condemnation

Much controversy exists surrounding the legality of prisoner isolation and, in particular, the existence of supermax prisons. Many researchers assert that the way in which prisoners are allocated to supermax prisons is a violation of due process rights.39 Many also assert that isolated confinement is a violation of the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids “cruel and unusual punishment.” In Hawkins v. Hall (1981), a court ruled that solitary confinement is not necessarily an Eighth Amendment violation; it depends on whether the deviation from prison housing norms is serious enough to qualify as a conditional violation and on whether the defendants acted with culpable intent.40 As a result, many arguments have thus far relied upon the physical conditions of the cells in which prisoners are confined for the purposes of proving isolated confinement sufficiently cruel or unusual.

In Rhodes v. Champman (1981), the Supreme Court established three criteria for evaluating prison conditions. First, the punishment must be proportional to the action requiring it. Second, the conditions should not involve the “wanton and unnecessary infliction of pain.”41 Finally, the conditions must not deprive prisoners of the “minimal civilized measures of life’s necessities.”42 It has also been established since 1971 in Novak v. Beto that prisoners do not lose their constitutional rights as a whole upon incarceration, including their Eighth Amendment rights, and that a prisoner does not “forfeit rights which do not conflict with his prisoner status or the ‘legitimate penological objectives of the corrections system.’”43 However, it has been shown to be fairly easy to argue that the improvement of poor conditions presents a threat to a prison’s “penological objectives,” and despite the Supreme Court’s conditions, there have been frequent rulings that prison conditions are acceptable even in the most extreme cases. For example, in McCord v. Maggio (1990), the court ruled that a case of isolated confinement in which human waste was seeping through broken pipes into the cell was constitutional, as the conditions of the cell were deemed related to the security measures, and thus the penological objectives, of the prison.44 Cells without light, limited bedding or the lack of a bed at all, and minimal food have all been held constitutional. In Jackson v. Meachum (1983), the court concluded that even prolonged solitary confinement may serve the interests of the prison system.45

Yet at the same time, the Supreme Court has recognized in many cases that solitary confinement is a gruesome, sometimes needlessly painful additional punishment. The Supreme Court ruled in re Medley (1890) that forty-five days of solitary confinement for James Medley, who was on death row, would be “an additional punishment of the most important and painful character” on top of the ruling sentencing him to death.46 There are many instances in which courts have ruled that long stints of isolation are unconstitutional, such as Hutto v. Finney (1978), in which thirty days was ruled too long, or in Sheley v. Dugger (1987) in which the court ruled that even when a prisoner was given adequate food and clothing, a twelve year solitary term was unconstitutional.47 At the same time, a court upheld ten months in Watson v. Coughlin (1988) and twelve months and eight days in Sostre v. McGinnis (1971) as serving valid security measures and as not sufficiently damaging so as to cause an Eighth Amendment violation, respectively. For the most part, courts have been unsympathetic towards, or unwilling to consider, the psychological impact of isolation on the prisoner.48 Only beginning in the 1990s have courts begun to recognize that the Eighth Amendment could apply to protections surrounding the mental health of prisoners, with one court noting that it would be “just as unconstitutional to make a prisoner mentally ill as it would be to make him physically ill.”49 Newer arguments center on the notion that psychological effects can be just as sufficient as evidence as physical effects for the condemnation of these practices.

While the United States has been reluctant to condemn solitary confinement, international standards are clearer. The United Nations condemns solitary confinement for more than fifteen consecutive days as a violation of human rights standards.50 Meanwhile, the Committee Against Torture (the governing body of the Convention Against Torture, of which the United States is a party), has recommended the abolition of solitary confinement due to the negative physical and mental health outcomes it creates in prisoners.51 Within the United States, organizations like Human Rights Watch, the American Civil Liberties Union, and The Marshall Project, among others, campaign actively against isolation.

VI. Failure to Achieve Goals

Solitary confinement not only fails to achieve the goals of safer or more efficient prisons but can also be extremely costly. For example, mental health effects, while devastating to the individuals who suffer through isolated confinement, also have an economic cost. For every one hundred acts of self-harm committed, approximately 3,760 hours of additional work is required from correction officers for things like transport to the hospital or suicide watch, costing a significant amount of money in paid labor.52 Supermax prisons, in particular, have been shown to cost up to three times more both to build and to operate.53 There is also minimal evidence that supermax prisons were ever necessary, no evidence that they operate on a sound, theoretical base or that they are cost-effective, and very little evidence that they are implemented consistently or able to achieve their intended goals.54

Furthermore, there exists evidence that isolated confinement can contribute to higher rates of recidivism, particularly in cases of direct-release, in which inmates are released from

prison directly from solitary confinement. In a 2007 study, 69 percent of direct-release inmates from a supermax prison were convicted of a new felony within three years of release as compared to 51 percent of non-supermax, non-direct-release inmates.55 Another study in Texas from 2015 found that 60 percent of state prisoners released directly from solitary were rearrested within 3 years, compared to 49 percent of overall prison releases56

There are many potential reasons for these higher rates of recidivism. One is, as previously mentioned, that long-term or permanent effects of solitary can damage returning citizens’ ability to perform regular jobs or interact in positive, prosocial ways. At the same time, aggressive impulses may cause damage to existing support systems, such as returning citizens’ relationships with family and friends. As a result, many returning citizens resort to criminal activity after the inability to find a job or rely on family or friends. Another potential reason is the lack of supervision by a parole officer for many direct-release returning citizens. When prisoners are released without supervision, recidivism is more likely.57 In Texas and in many other states, parole boards consider the disciplinary history of a prisoner when deciding whether to grant early release. If a prisoner’s record includes solitary confinement for disciplinary purposes, they may not qualify, and will instead “max out” their full sentence and be released directly from solitary. In Texas, prisoners who are mentally ill (as many of those in solitary are) and under the care of a parole officer upon release will be referred to mental healthcare providers in the community, but without any supervision, they may receive as little as a directory with the contact information of healthcare professionals, or sometimes, no referrals at all.58 In some instances, prisoners with mental health diagnoses leave prison without even a record of their prescriptions. 59 This lack of support and resources can even further exacerbate mental illness, keep returning citizens from getting the healthcare that they need and contribute to higher rates of recidivism.

VII. Reimagining Solitary Confinement

It is clear that solitary confinement does not achieve the intended goals of providing a safe environment or a way to deal with threatening or dangerous inmates. As such, it is necessary to seek out new ways of handling dangerous inmates or inmates committing infractions. Because such a high percentage of inmates being placed in isolated confinement are mentally ill, one method of addressing the overuse of solitary confinement with this population is to provide better training for the correctional officers that interact with mentally ill prisoners.

Correctional officers are considered constitutionally obligated to provide general medical care to inmates. However, many are unequipped to address the specific challenges associated with the disruptive behavior that can be caused by mental illness, especially psychosis.60 Correctional officers are frequently the ones making decisions about whether to place inmates in isolation, but due to a lack of understanding about mental illness and its symptoms, mentally ill prisoners may be perceived as threatening or dangerous and are placed in disciplinary segregation more frequently.61 Officers interviewed in a 2009 study reported that working with mentally ill offenders added stress to their jobs even when they were confident in their ability to work with general jail populations. The high psychological demands of the job and low levels of institutional support often cause feelings of insecurity or fear of violence.62 This combination of the genuinely disruptive symptoms of mental illness and correctional officers’ heightened stress surrounding the issue leads mentally ill offenders to be written up more frequently, with 58 percent of mentally ill offenders receiving citations as compared to 43 percent of non-mentally ill offenders.63

Despite these difficulties, nearly all officers interviewed as part of the same 2009 study were interested in further training on how to work with mentally ill offenders.64 Training programs for correctional officers regarding mental illness in the prison population would thus likely be well-received. One example of a possible program was run by the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) in February and March of 2004 at the Indiana Department of Correction’s Carlisle facility. Nine months before the first training, the special housing unit was full to 98.5 percent of its capacity and there were 162 violent incidents between correctional officers and inmates. Nine months after the second training, the monthly census had dropped to 87.0 percent of capacity, with only 63 violent incidents occurring65 Other research suggests that in addition to a generalized training on mental health disorders, correctional officers could be trained to provide mental health services, such as therapeutic conversations or observing medication and its side effects.66 Training correctional officers to address issues and symptoms of mental illness in a non-punitive way is a promising attempt to replace solitary confinement as a disciplinary measure without disregarding the safety concerns of prison staff.

Another promising example of changing policies regarding the isolation of prisoners is Maine’s campaign to reduce the use of solitary confinement. Between 2011 and 2012, the Maine Department of Corrections made significant changes to send fewer prisoners into isolation and to shorten the length of time that any prisoner would spend isolated. By August of 2012, approximately half as many prisoners were being held in isolation as in 2011.67 Conditions for isolated prisoners also improved significantly, following psychiatrist recommendations to provide isolated prisoners with access to radios, televisions, and reading materials to decrease the likelihood of negative isolation-related mental health symptoms. Prisoners are also given more opportunities to participate in group recreation or counseling sessions even while being held in separate, semi-isolated housing.68 Due to Maine’s progressive policies, prisoners have long been afforded a hearing before being placed in disciplinary segregation, but under the new policies, alternatives to disciplinary segregation are available, such as restricting visitation to the immediate family only, temporarily taking away work opportunities, or confining the prisoner to their own cell. Disciplinary segregation is now only used when the prisoner is a direct escape risk or poses a threat to their own or others’ safety when not restricted.69 Maine has also implemented new training programs for correctional officers, one of which is named “verbal judo” and is meant to replace some of the firearms and self-defense training that correctional officers used to receive, emphasizing the need for non-violent de-escalation of conflict and the idea that violence should be a last resort.70

Finally, prisoners are made aware when they enter segregated housing that it should be temporary and last for as little time as possible. Prisoners placed in isolation are given a clear path based on achievable goals to ending their solitary confinement, part of which involve meetings with mental health staff or correctional caseworkers and the goals of controlling impulses and avoiding self-harm or ideation of harm.71 Overall, the program has helped to reduce the use of solitary confinement, prevent the mental deterioration of those who are temporarily isolated, and to de-escalate conflicts within prisons.72 Adopting a similar model across the United States as well as implementing correctional officer training programs similar to that of the Carlisle facility would help to reduce the negative effects associated with isolated confinement without disregarding the need to address inmate infractions or general safety.

VIII. Conclusion

Overall, the solitary confinement of inmates, particularly those suffering from mental illness, is counterproductive to ensuring the safety of inmates and staff. Based on an abundance of evidence suggesting that isolated confinement has negative long-term impacts on inmate health, rates of recidivism, facility disorder, and economic cost of incarceration as well as the multitude of arguments condemning the use of such a practice both morally and legally, it is necessary that the United States adopt new policies to replace its use. A reimagining of the role that solitary confinement plays in the incarceration system is long overdue. With Maine’s reforms as a primary example, the United States can and should begin a shift away from the normalized use of isolated confinement.

- Peter Scharff Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” Crime and Justice, 34, no. 1 (2006): 441-528. doi:10.1086/500626.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” 445.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” 445-446.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature.”

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” 457.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” 459.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” 457.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates: A Brief History and Review of the Literature,” 469-470.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates” 443-444.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 443.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 448.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 443.

- Mears, D. P. (2006). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Supermax Prisons (pp. 1-67, Rep.). Urban Institute Justice Policy Center.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates.”

- US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails, 2011-2012 (BJS Publication No. 249209), 2015.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 453.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 453.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 452-453.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 489.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates, ” 490.

- Stuart Grassian, “Psychopathological Effects of Solitary Confinement,” American Journal of Psychiatry 140, no. 11 (1983): 1452. doi:10.1176/ajp.140.11.1450

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 491.

- Grassian, “Psychopathological Effects of Solitary Confinement,” 1453.

- A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- ACLU of Texas, 2015.A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 482.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 499.

- Fatos Kaba et al., “Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-harm among Jail Inmates,” American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 3, (2014): 442-7.

- Kaba et al., “Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-harm among Jail Inmates,” 444-5.

- Kaba et al., “Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-harm among Jail Inmates,” 444.

- Kaba et al., “Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-harm among Jail Inmates,” 446.

- Kaba et al., “Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-harm among Jail Inmates,” 446.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails.

- US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, National Institute of Justice, Administrative Segregation in U.S. Prisons – Executive Summary, (NIJ Publication No. 249750), 2016.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails.

- Bureau of Justice Statistics, Use of Restrictive Housing in U.S. Prisons and Jails.

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 444.

- Bryan B. Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” Law and Psychology Review 21 (1997): 271.

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 274.

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 274.

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 274.

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 274

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 282

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 467.

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 283

- Smith, “The Effects of Solitary Confinement on Prison Inmates,” 444.

- Walton, “The Eighth Amendment and Psychological Implications of Solitary Confinement,” 283.

- David H. Cloud, Ernest Drucker, Angela Browne, and Jim Parsons, “Public Health and Solitary Confinement in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 105, no. 1 (2015): 24.

- Cloud et al., “Public Health and Solitary Confinement in the United States,” 24.

- Kaba et al., Solitary Confinement and Risk of Self-harm among Jail Inmates,” 446.

- Daniel P. Mears and William D. Bales, “Supermax Incarceration and Recidivism,” Criminology 47, no. 4 (November 2009): 1135. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00171.x.

- National Institute of Justice, Administrative Segregation in U.S. Prisons, 2016.

- Mears & Bales, Supermax Incarceration and Recidivism,” 1135-6.

- A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- A Solitary Failure: The Waste, Cost and Harm of Solitary Confinement in Texas (pp. 1-57, Rep.). (2015). Houston, TX: American Civil Liberties Union of Texas.

- George F. Parker, “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit,” Psychiatric Services 60, no. 5 (May 2009): 641, doi:10.1176/appi.ps.60.5.640.

- Parker, “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit,” 640.

- Parker, “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit,” 643.

- “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit,” 641.

- Parker, “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit,” 643.

- Parker, “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit.”

- “Impact of a Mental Health Training Course for Correctional Officers on a Special Housing Unit,” 643.

- Change is Possible: A Case Study of Solitary Confinement Reform in Maine (pp. 1-38, Rep.). (2013). Portland, ME: American Civil Liberties Union of Maine.

- ACLU of Maine, 2013.

- Change is Possible: A Case Study of Solitary Confinement Reform in Maine (pp. 1-38, Rep.). (2013). Portland, ME: American Civil Liberties Union of Maine.

- Change is Possible: A Case Study of Solitary Confinement Reform in Maine (pp. 1-38, Rep.). (2013). Portland, ME: American Civil Liberties Union of Maine.

- Change is Possible: A Case Study of Solitary Confinement Reform in Maine (pp. 1-38, Rep.). (2013). Portland, ME: American Civil Liberties Union of Maine.

- Change is Possible: A Case Study of Solitary Confinement Reform in Maine (pp. 1-38, Rep.). (2013). Portland, ME: American Civil Liberties Union of Maine.