An Exploration of the Origins of the Criminalization of Blackness and its Modern-day Representations

The Criminal, the Other, and the Black Man

Introduction

An essential contribution to the persisting racial disparity in the United States today is the negative representation of Black men. During the institution of slavery, dating as far back to the 1440s with the Portuguese’s trafficking of African captives, to the 1800s abolitionism in The United States of America, the perception of Black people, particularly Black men, was that of docility. Black people who were enslaved were viewed as having the fundamental characteristics of buffoonery, naive ignorance, and adolescent angst. Prejudices and misconceptions that are created and spread through a variety of media sources such as the news, particularly in the twenty-first century frequently portray Black men as violent, aggressive, and dangerous. This reinforces the assumption that they are more prone to be involved in criminal activity. This misconception is detrimental to Black men as individuals and the Black community. The portrayal of Black men in the media affects how they are regarded by the police, workplace, and society. The negative representation of Black men is an essential factor in the persisting racial disparity in the United States today. Our paper looks at how the marketing of American culture, specifically in television and film, has painted and continues to paint the Black male as a criminal. We chose to investigate the news media, television, and film, as significant variables that lead to the perception of Black men as “dangerous and criminal.” The media has a widespread propensity to overrepresent African Americans as criminals, portray Black men as especially dangerous, and offer information about Black suspects that assumes their guilt. However, even when a crime involving Black and white criminal suspects is reported in the news media, viewers’ existing assumptions might result in biased interpretations that serve to perpetuate racial stereotypes.

Numerous studies have examined the portrayal of Black men in the media. According to one study, in music videos and movies, Black males are more frequently depicted with guns and in violent settings than white men. Even if they were not the culprits, Black men were more likely to be shown in press coverage of crime. This type of coverage fosters the false notion that Black men are more likely to be involved in criminal activity. According to the article “Crime News and Racialized Beliefs: Understanding the Relationship Between Local News Viewing and Perceptions of African Americans and Crime,” exposure to the overrepresentation of Black people as criminals on local news shows, attentiveness to crime news, and trust in the news predicted perceptions of Black people and crime. This survey revealed that attention to crime news was strongly associated with harsher culpability evaluations of a hypothetical race-unidentified suspect and a Black suspect, but not a white suspect. Also, greater exposure to the overrepresentation of Black people as criminals on local television news was positively associated with the view of Black people as violent.1

Historical Background

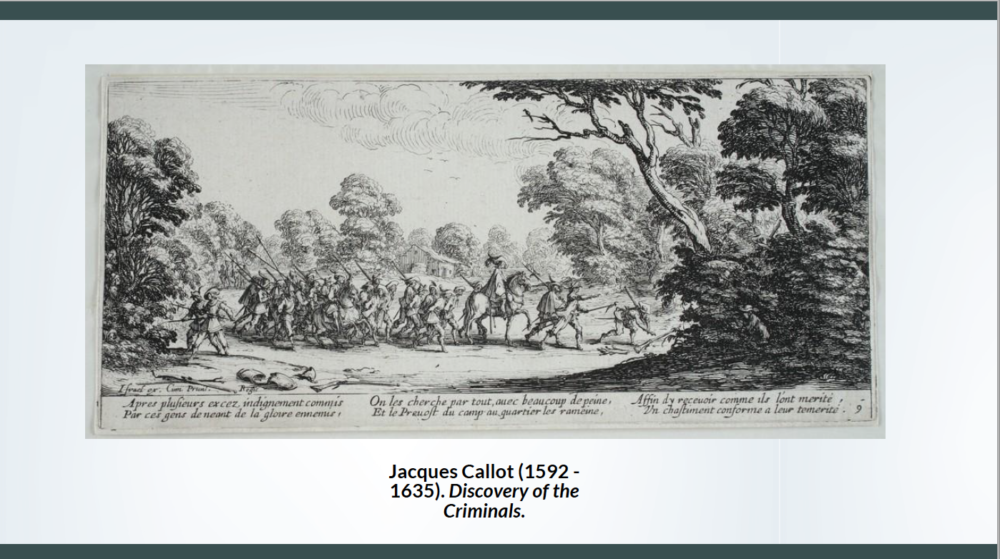

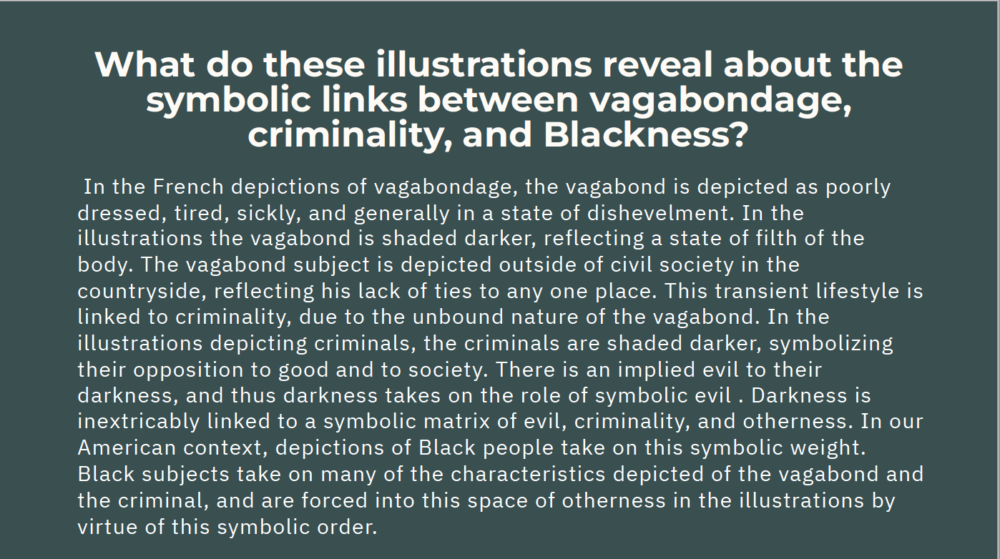

What is a society without the criminal? What is a society without the other? In our American context, othering is used as a tool for systematic social division and a psychological force of unification. The other is always criminal, and the criminal is always imbued with the negative characteristics believed to be antithetical to society. The criminal is unproductive, anti-social, unbound from morals, and thus dangerous, dirty, and unfit for humanity. There have been countless groups of people in the American context that have been othered and criminalized, but no group has held this position of absolute other like Black people. This position of otherness is held so powerfully that the dichotomy of black-white has seemingly taken on a wholly unique form of racialization.

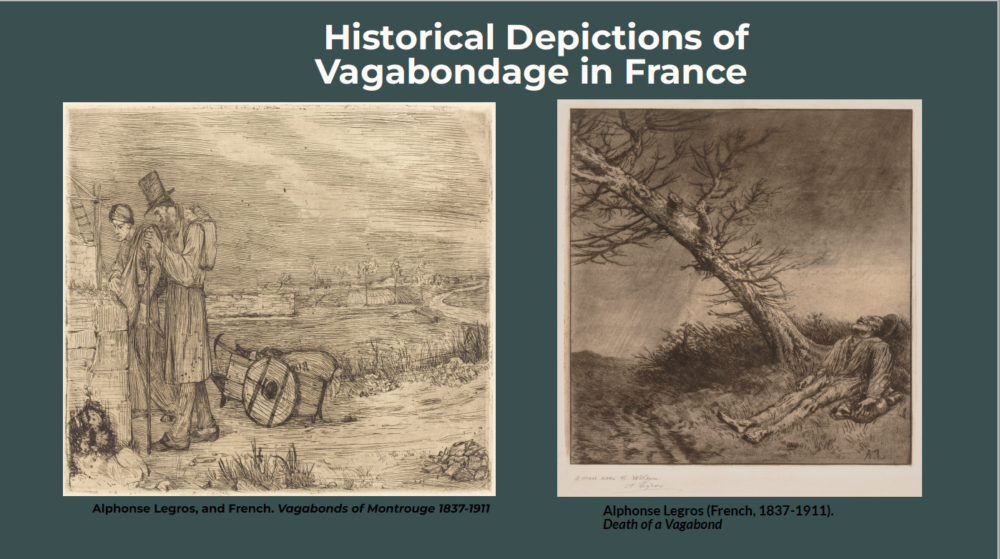

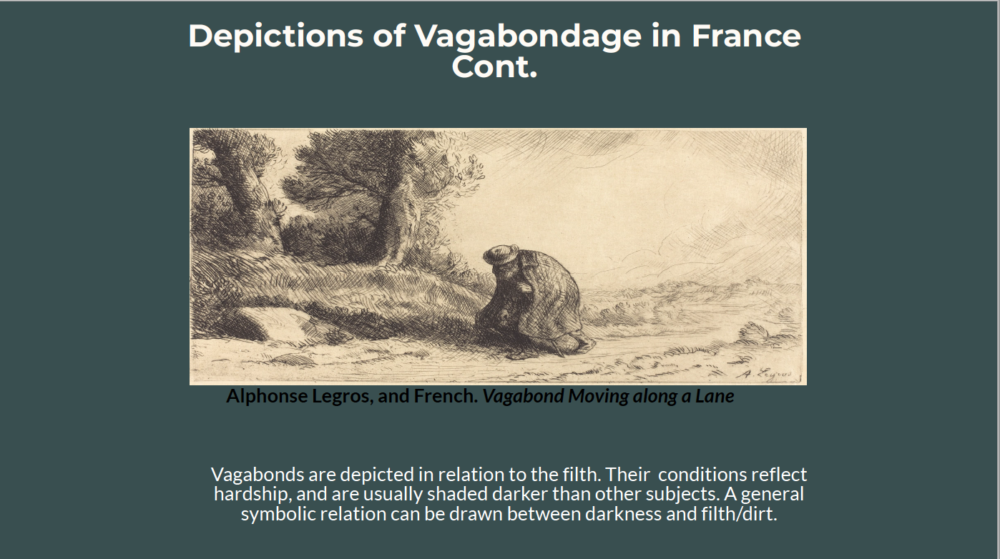

In Michel Foucault’s Punitive Society lectures, he describes the history of the criminalization of the vagabond by outlining Le Trosne’s description, which illustrates the vagabond as a stateless people antithetical to French society. The vagabond is conceived of as the wandering person who consumes but does not contribute to society, “they live in society without belonging to it; they live in society in the condition that we suppose existed before the establishment of civil societies.”2 To combat the negative effects this population poses to society, Le Trosne puts forth four solutions: enslavement, physical branding to mark their status as slave, arming and deputizing of peasants, and killing anyone who “refused to be settled.”3

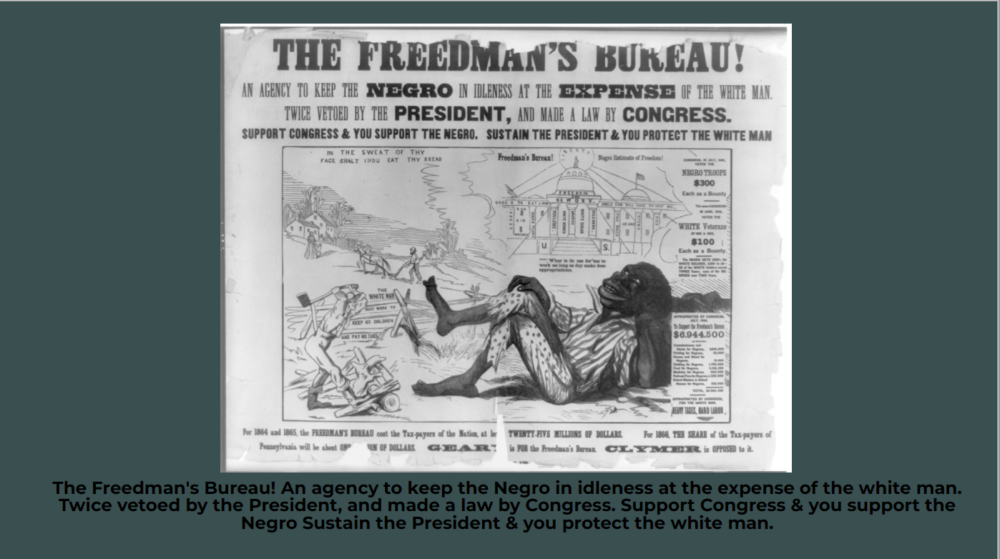

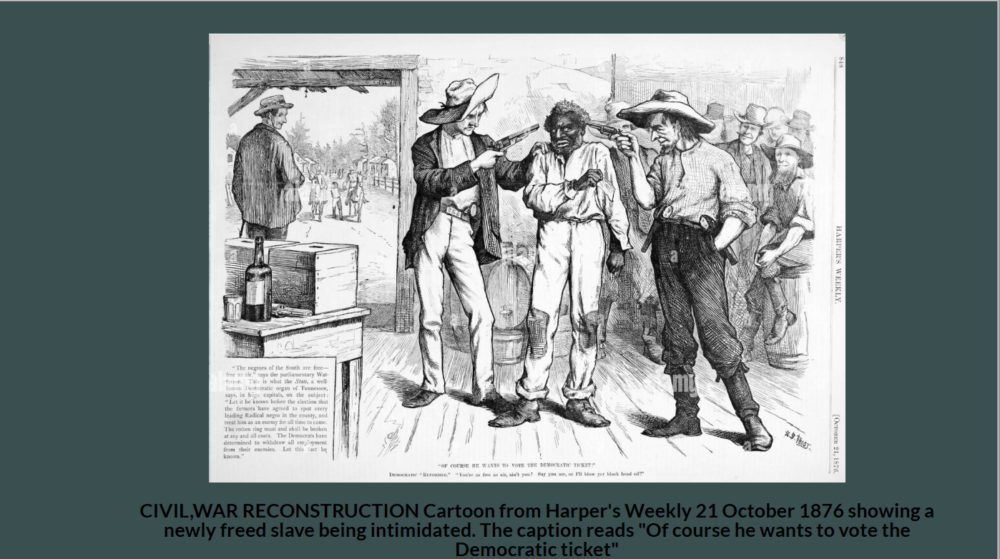

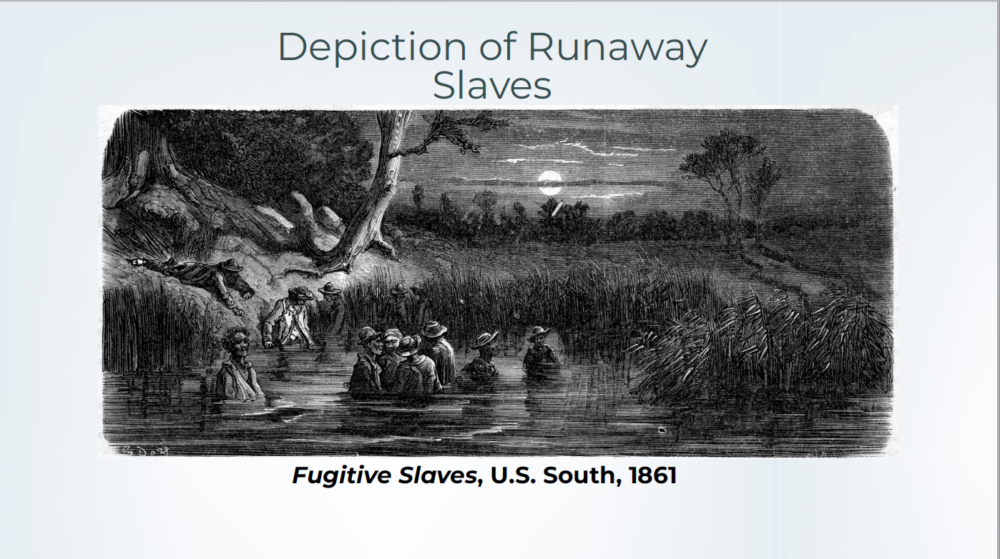

In this brief description of tactics used to combat the vagabond class in 18th century France, we can already draw connections to American slavery and its consequences. In W.E.B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction in America, speaking about postbellum America, Du Bois describes the system of laws enacted to combat the newly freed population. Du Bois explains, “in Georgia it was ruled that “all persons wandering or strolling about in idleness, who are able to work, and have no property to support them; all persons leading an idle, immoral, or profligate life…shall be deemed and considered vagrants, and shall be indicted as such , and it shall be lawful for any person to arrest said vagrants and have them bound over for trial.”4 The punishment for such vagrancy was imprisonment and forced labor. These laws were common place in many states, and were implemented specifically in response to the new “vagrant” population of freed slaves. This “idle” population posed an existential threat to the economic and social order of the South. Not only had their entire economic system been upended by the Civil War, but they then had a large population of stateless people who must either be integrated, expelled, or exterminated. Even in the late eighteenth century this vagabondage posed a threat to society, Du Bois writes of antebellum America, saying, “as slavery grew to a system and the Cotton Kingdom began to expand into imperial white domination, a free negro was a contradiction, a threat and a menace. As a thief and a vagabond, he threatened society; but as an educated property holder…he more than threated slavery…he must be suppressed, enslaved, colonized.”5

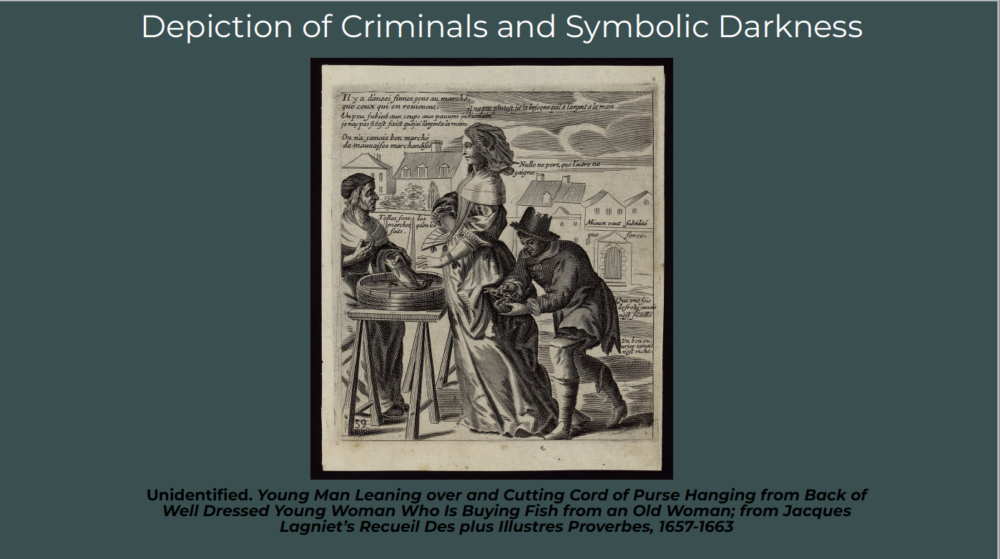

The striking similarity between language and tactics of the European and American vagrancy problem is likely no coincidence, given that the systematic othering of unwanted classes was not a new issue; however, in the American context skin color presented the added advantage of a biological branding onto which the other can instantly be recognized as other, or criminal. Nevertheless, the characteristic traits of the racialized other seem to remain the same regardless of the population. Foucault cites a physician’s account of social classes in Brest, France in 1830, who describes the state of the proletarians. The physician’s account reads: “of a proportionally immense extent, which, apart from a few honorable exceptions, possesses profound ignorance, superstition, ignoble habits, and the moral depravity of wild children. Its triviality, rustic simplicity, improvidence, and extravagance, in the midst of ludicrous pleasures and orgies, cannot be expressed.”6 These characteristics can generally be described as being related to depravity or lack of civility. These same characteristics were used to describe the savagery of Black people and Native Americans. In most cases, the racialized other maintains this negative position in relation to society. The hated other must possess the negative characteristics of humanity, in order to justify their subjugation or extermination. In other words, the racialized other comes to hold a symbolic position representing the opposite of society. This racialized other may appear to be antithetical to society, but it’s only through the negation of the other that society is able to positively construct itself.

Given that racialization, or the criminalization of the other, is a social characteristic predating our conceptions of Black-white racism, how can we understand the peculiar importance of skin color to the concept of racialization? In Joel Kovel’s, White Racism, Kovel points to the relationship between the symbolic importance of color to the psyche of the individual; in addition to this relationship, Kovel examines the significance of the symbolic to culture, ultimately arguing that racism is, in stronger words, an unfortunate coincidence in the confluence between a symbolic matrix and reality. He emphasizes culture as a unificatory force, arguing “amidst its more rational structures, culture comes to play a role of immense importance in the stabilization of the human personality. To fulfill its vital role, however, culture must be organized along lines which reflect symbolically the inner splits and drives of personality.”7

Kovel’s argument relies on the psychoanalytic construction of the individual about unresolved conflict stemming from infantile development. Essentially, he argues that the psychic splitting that occurs in the process of development results in the projection of “bad” feelings onto another and the introjection of “good” feelings into itself; he says, “the split between a good body, which belongs to the self, and a bad body, which is expelled, becomes generalized to the rest of reality. An enduring polarization between good and bad aspects of the world is built on the foundation of body symbolism. Beyond the body, objects are sought in the outer world as suitable to represent both loved and hated parts of the self.”8 Thus, he argues that “racism abstracts the color of the living body into non-colors of extreme value, black and white. Within this organization, black represents the shade of evil, the devil’s aspect, night, separation, loneliness, sin, dirt, excrement, the inside of the body; and white represents the mark of a good, the token of innocence, purity, cleanliness, spirituality, virtue, hope.”9 In this construction, we can understand why Black-white racism holds such a thorough grasp on our society. The connection between skin color and the symbolic role of “darkness” provides a “rational” and easily identifiable “other” to project the individual’s and society’s most hated feelings onto. The “dirt” and “darkness” that symbolized the impoverished classes in some ways logically transferred onto the dark skin of the stained other; Blackness thus took on the already established ontological evil of darkness and the other. Even if one were to reject Kovel’s explanation of the psycho-historical origins of the hatred of Blackness, his insights attempt to breach the undeniably peculiar characteristics of Black-white racism that extend far beyond biological explanations.

Discussion

The criminalization and othering of Blackness simultaneously take on a sociocultural role of stabilization, operating as a proactive defense in maintaining class by systemic means. Most importantly, this racialization provides an identity that supersedes any material rationality, ensuring class division vertically (rich to poor) and a perpetual disunification of the lower classes. This disunification is especially vital to maintaining the economic stratification of American society. Du Bois explains:

Slavery bred in the poor white a dislike of Negro toil of all sorts. He never regarded himself as a laborer or part of any labor movement. If he had any ambition at all, it was to become a planter and to own “niggers.” To these negroes he transferred all the dislike and hatred he had for the whole system. The result was that the system was held stable and intact by the poor white.10

At moments when this symbolic othering has faltered, the class system was existentially threatened, and the demise of society in its specific construction was imminent. The “motley crews” of the eighteenth century posed an ideological threat, and thus existential, to the American “Revolution”; Marcus Rediker writes, “the motley crew thus provided an image of revolution from below that proved terrifying to Tories and moderate patriots alike. In his famous but falsified engraving of the Boston Massacre, Paul Revere tried to make the ‘motley rabble’ respectable by leaving black faces out of the crowd and putting into it entirely too many gentlemen.”11 One interpretation of this revision may be that by making the crowd more respectable, they could garner more generalized support; however, a more critical reading of this revision reveals an intentional desire to maintain a symbolic separation between Black and white. Even in this early system, when racial ideology wasn’t as developed as in the next century, by erasing Black faces from the revolution, the process leaders could ensure the new nation would be constructed in their image, both literally and symbolically.

The explicit repudiation of the motley crew by the ruling elite of the revolution ensured that this revolution did not become an uprising from the lower classes like other contemporary revolutions but instead remained a war of the wealthy. The symbolism of the American Revolution was still energetically maintained by the spirit of liberalism and the enlightenment. Still, as time would prove, these ideas would only apply to specific populations. The motley crew symbolized the unification of the lower classes, which would naturally result in a system of opposition to the ruling class. In short, the American “Revolution” constructed a matrix of symbols through language and images to populate the new cultural imagination; however, this revolution was but a simulacrum intended to maintain society in its specific economic form ultimately. The particular construction of the Black-white dichotomy proved to be an effective tool of influence in the years after the revolution in stabilizing the new nation.

The persistence of the Black racialized other is upheld through history, language, and mass culture. History, as it’s told, functions as an authority that justifies our lives present. Language serves as a tool of mystification and obfuscation to create the illusion of the omnipotence and primacy of whiteness and the subordination and secondary nature of Blackness (otherness). As the result of the overwhelmingly negative depictions of Black people in the media, mass culture functions as the vehicle in which the criminalization of Blackness is most energetically maintained.By briefly explaining the possible origins of why Black-white racialization holds such an essential psychical role in the individual and its role as a necessary social stratification, we can begin to explore how the cultural conflation between the Black person and the criminal manifests in our current day.

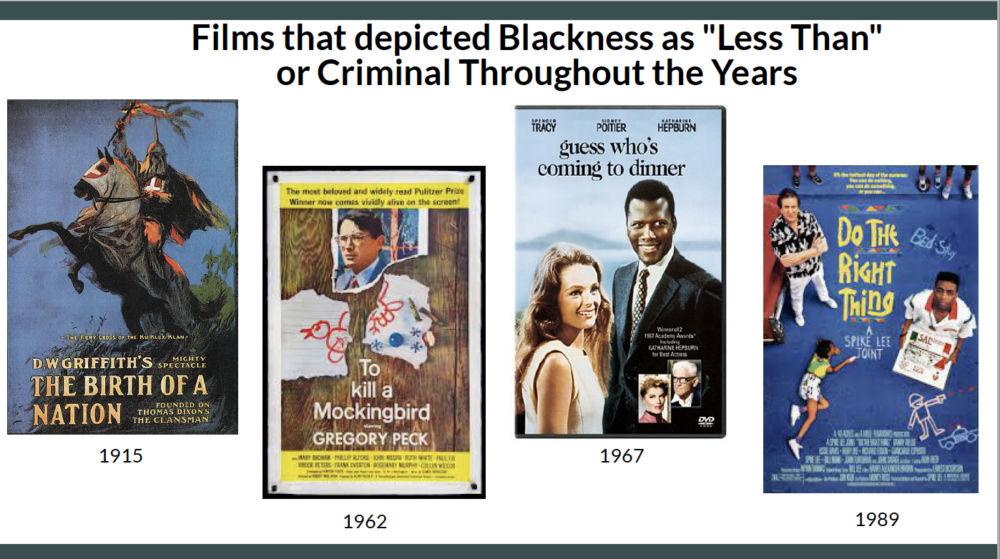

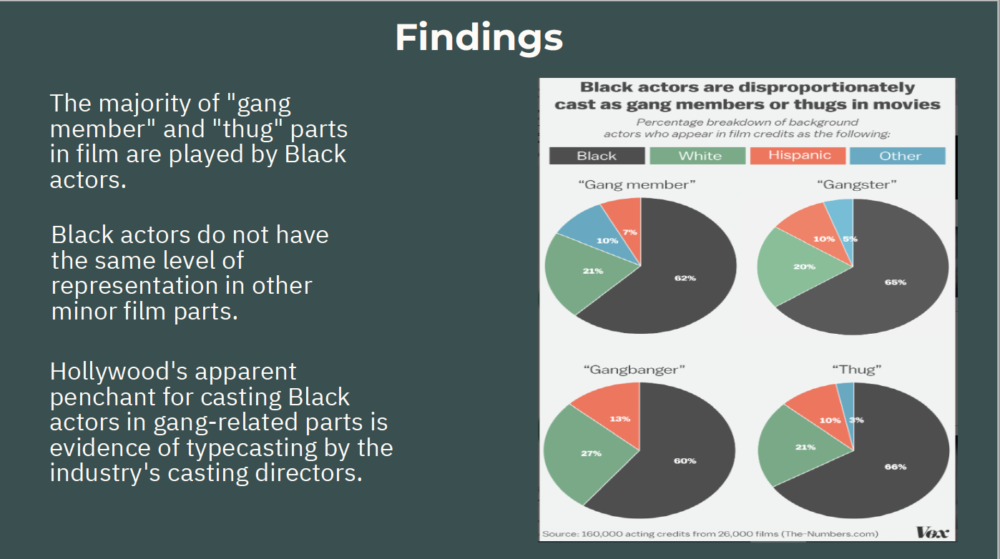

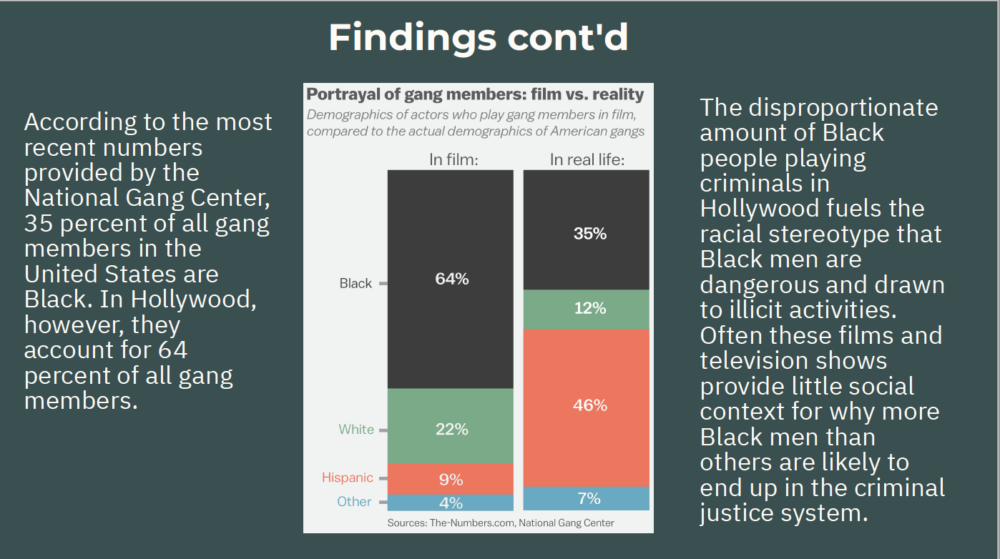

Additionally, beyond the history of race relations in America, media portrayals have also contributed to the mistreatment of African Americans. While numerous media outlets have demonstrated this negative picture of African Americans, the film industry has also been used to characterize groups of people. Hollywood has traditionally had a significant impact on American ideology. Films can be used for a variety of goals, such as promoting a message or raising awareness about particular societal issues. However, films frequently exaggerate the characteristics of various ethnic/racial groupings. This results in a broad and frequently offensive perception of minority groups. For instance, the film Birth of a Nation portrayed African American males as illiterate, savage brutes who preyed on defenseless white women. The politics of the movie were crucial in arguing that Black people, in particular, were deserving of the death penalty or lynching. They also portrayed the Black man as a rapist, embodying the stereotype of the Black man with eyes only for white women. The movie makes the case that granting Black people civil rights was a terrible mistake and that they committed all kinds of horrible crimes when, in reality, they didn’t. It portrayed African Americans in such a negative light that its stigmatization still plagues the Black community.12 Black characters in movies are frequently shown in clichéd roles (thug, pimp, gangster), which promote the criminal label African Americans and their culture have been given. This fosters long-standing notions that African Americans are inherently criminal and exacerbates the prejudices maintained by the white majority against African Americans.

In filmic depictions of African Americans, appropriation and exploitation of African American culture are also evident. White America has frequently been captivated by the material and immaterial charms of African-American culture. Films like Malibu’s Most Wanted, Get Hard, and White Men Can’t Jump, exploit African American culture for a largely white audience. This is accomplished by placing a white character in a stereotypically black environment and recounting the story through the white character’s perspective using generic and stereotypical actions, imagery, and conversation so that the white character fits in with the Black population. This ultimately makes the white character a master of adaptation when dealing with the African American population. The media, particularly the film industry, have not been remiss in exploiting the traditions and conventions frequently associated with African Americans. This is obvious in the 1970s Blaxploitation film genre.13 In the book Social Death, Cacho argues that America has so strongly connected Blackness with criminality that we cannot identify a crime without a Black body. She explains that this is due to the assumption that white people do not commit these crimes. Therefore, since a Black body is required for the crime to be recognized, African Americans cannot fully escape the criminal identity due to their intrinsic Blackness.14

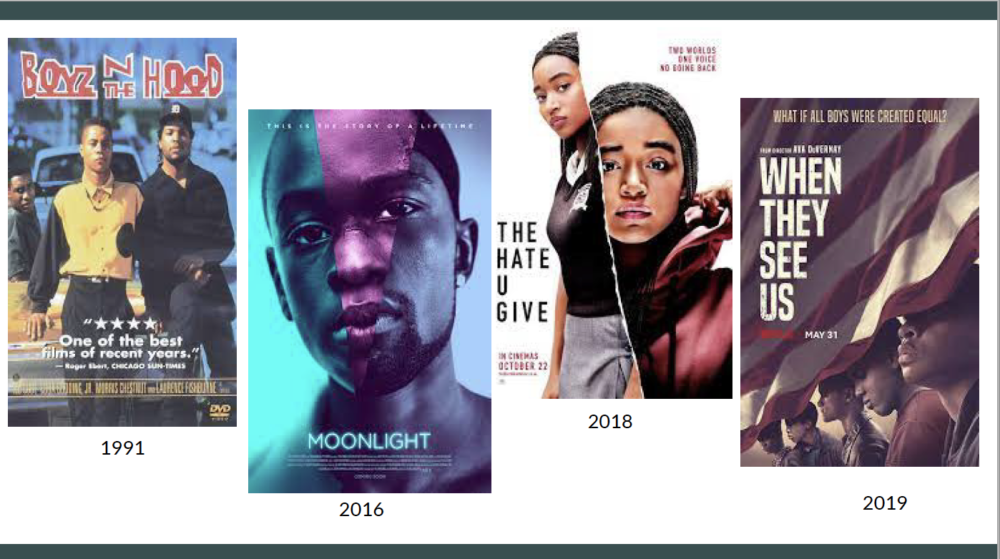

Hollywood and the American film industry are regarded to be a literal depiction of the country’s beliefs, with many spectators viewing the works shown on the big screen as absolute reality. This phenomenon has spread internationally, with people from foreign countries considering American-made films as the “reality” of how American culture operates. These films allow many individuals who have never visited the United States to experience American culture vicariously. Some people may never experience life in the United States outside of movies. In this case, the film industry serves as a vehicle of communication through which individuals from around the world can observe the pervasive American way of life. Furthermore, many Black entertainers employ stereotyped and satirical material as a source of humor and narrative. However, although appearing innocent, this form of entertainment may promote negative perceptions about Black people due to the prevalence of sex, vulgarity, poor living conditions, lack of social skills, and violence. A very recent case was the Oscars incident with world-renowned Black actor Will Smith who slapped Chris Rock, a renowned comedian, for disrespecting his wife as a “joke” for making fun of her alopecia. This situation has caused people who are not Black to view the Black community as scary, angry, and vicious. However, currently, it appears that Black culture and people are afforded increased positivity in Hollywood. Get Out (2017), The Black Panther (2018), Into the Spider-Verse (2018), and most recently Us (2019) indicate that films with Black stars may not only achieve critical acclaim but also be commercially successful. In comparison to prior films depicting Black culture, these films depict Black people and their culture in a more positive and uplifting manner, by showing the systemic racism in our society, the othering of Black men or Black bodies and our fortitude to rise above oppression, instead of depicting Black men as creatures of harm, vagabonds or criminals. This trend emphasizes the favorable portrayal of Black people and their culture in film.

Conclusion

Our article examined the relationship between the media and American attitudes toward crime. The selected media format was film. We highlighted the significant influence that film has played in shaping how African Americans are seen in the United States and how Black people are viewed globally. Unfortunate side effects of this portrayal include the exaggeration, misrepresentation, and misinterpretation of particular characteristics when the conditions depicted in the film are not viewed as that of what is true about Black men typical. The film largely demonstrates this inability to distinguish between Black man and the racist ideologies perpetuated by the white race about Black men. Since the first screening of the 1915 film Birth of a Nation, African Americans have been connected with criminalized depictions. Hollywood and the American film industry are regarded to be a literal depiction of the country’s beliefs, with many spectators viewing the works shown on the big screen as absolute reality. This phenomenon has spread internationally, with people from foreign countries considering American-made films as the “reality” of how American culture operates. These films allow many individuals who have never visited the United States to experience American culture vicariously. Much of the responsibility for change falls on Hollywood’s willingness to acknowledge the skewed portrayal of Black people and their culture and make serious efforts to implement the necessary improvements. However, those of us belonging to the Black culture remain positive that change is imminent, especially with authors and creators such as George Tillman Jr (The Hate U Give) and Ava DuVernay (When They See Us) who have been creating more roles for Black people that are positive and fun, as well as enlightening the world on the injustices our Black men face in society, a shift from what the world has been used to seeing in the decades prior to now.

- Travis L. Dixon, “Crime News and Racialized Beliefs: Understanding the Relationship between Local News Viewing and Perceptions of African Americans and Crime,” Journal of Communication 58, no. 1 (2008): 106–125., doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2007.00376.x.

- Michel Foucault, et al., The Punitive Society: Lectures at the College De France, 1972-1973 (Picador, 2018), 49.

- Foucault, The Punitive Society, 51

- W.E.B. Du Bois and David Levering Lewis, Black Reconstruction in America (Free Press, 1998), 174.

- Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 7.

- Foucault, The Punitive Society, 172.

- Joel Kovel, White Racism: A Psychohistory (Columbia University, 1970), 283.

- Kovel, White Racism, 269.

- Kovel, White Racism, 232.

- Du Bois, Black Reconstruction in America, 12.

- Marcus Rediker, Outlaws of the Atlantic: Sailors, Pirates, and Motley Crews in the Age of Sail (Beacon Press, 2015), 112.

- M. W. Hughey, “Cinethetic Racism: White Redemption and Black Stereotypes in ‘Magical Negro’ Films,” Social Problems, 56, no. 3 (2009): 543-577.

- Robinson, Blaxploitation and the Misrepresentation of Liberation.

- Lisa M. Cacho, Social Death: Racialized rightlessness and the criminalization of the unprotected, (New York University, 2012).