I had never thought of a slave witnessing a volcano before; that specific scenario was not conceivable in my reality. As someone who had always longed to connect with the ghosts of my shared diasporic past, I had to know: How did slaves react to a volcano? My project was an attempt to communicate with history and, hopefully, sew together any holes left by neglect.

Volcano Quilting

Foreword

When I first heard about the 1812 eruption of La Soufrière, I remember feeling particularly empty. The day itself was not so somber; in actuality, it was an exciting morning for me. While I cannot say I knew much about volcanoes back then, or really much about science in general during my time in Volcanoes: The Sublime and the Scientific, I was, and still am, drawn to their mystery. And every time I came to class was another chance for me to understand a phenomenon that had felt so unfamiliar. I was pleasantly surprised to find out that Professor Holmberg had invited a guest lecturer—a Black volcanologist at that—to share her research and wisdom with me and my peers. In all honesty, I never expected to learn about such a niche, specialized topic from someone who looked like me and saw the world with similar eyes. When Dr. Jazmin Scarlett spoke that morning, she told us about St.Vincent and the Grenadines, her childhood home, and how the 1812 volcanic eruption of La Soufrière had disrupted the island’s plantation economy, and more pertinently, the lives of enslaved Africans.

For some reason, this left me stunned. I had never thought of a slave witnessing a volcano before; that specific scenario was not conceivable in my reality. Of course, this is illogical; considering how widespread plantation slavery was, why wouldn’t a slave have lived in the midst of eruption? Volcanoes existed long before our time and surely will after, and yet, in my mind, plantation slavery and volcanic eruptions seemed to belong to separate worlds. At the time, my image of plantation slavery was still heavily aligned with the American South, and since I grew up in that region, I was never fearful of volcanic activity. But for the people of St.Vincent, both historically and in the present, La Soufrière shaped the landscape of their lives. At that moment, I realized that in order for me to fully grasp the geographical scope of plantation slavery, I would also need to come to it with a more scientific eye. I was perplexed, and as someone who had always longed to connect with the ghosts of my shared diasporic past, I had to know, How did slaves react to a volcano? What did they do, exactly? Within the violent constraints of slavery, I am sure they could not have done much, unfortunately. But who did they pray to when the sky turned black? And when the dust finally settled, how did they remember this moment in time? How did they grieve? Did they sing of folk legends, of flying away from the plumes of ash and the mountains of chains? And what about the slaves who were new to this world, who had never seen a volcano before? Did bewildered eyes look to the earth as if it were breaking? Did they create art and food to cope, to heal with one another? Did they cry or dance or sleep or suffer? How did a St.Vincentian slave in 1812 respond to La Soufrière’s eruption? We don’t know, was the answer Dr. Scarlett gave me. We don’t have anything left.

There is a certain kind of hollowness that occurs when you ask a question to history and it cannot answer you back. As any lover of the field knows, old materials and records are lost to the weathering of time, and it is often inevitable for assumptions about the past to be made. We can never truly have the fullest picture of history because we were not there. From our position in the present, we are forever contemplating a series of incomplete stories. But there is a difference between an archive of fragments and an archive that is purposely made empty by negligence and erasure. We know that European eyes gazed at La Soufrière with grim fascination and terror because that history is recorded for us in legal documentation, in firsthand accounts, and in pamphlets and testimonies. But we do not know, and may never know, if an enslaved African mother wrote a tearful letter to her children worrying for their safety. Those traces of life are not with us anymore. They are not in the archives of History or Science. They exist outside of the preserved and protected, out there, somewhere, no longer within our reach. Yet again, we are confronted with the painful truth that some histories are sought after and cared for more tenderly than others. To be a Black historian is to continuously mourn for the lives of ancestors we will never know the names of.

What do we do when we cannot find anything? It is a heartbreaking question to consider, especially when we know that so much of the history of plantation slavery—from material objects, to records of daily life, to the memories of people—may never be recovered or properly named. I believe that there is a way for us to bridge this boundless gap of knowledge if we look to the traces and traditions our ancestors have left behind. But with any prayer, an ounce of faith will be needed for this kind of contemplation. If we do not know how a St. Vincentian slave reacted to a volcanic eruption, then examining how other slaves throughout the African Diaspora responded to their sudden traumas could be an option for us. It may be possible that the best way to communicate with our past, to truly validate the ways in which they spoke, crafted, and recorded their own histories, is to sustain the rituals and practices of our inheritance. My volcano quilting project was a personal introspection as much as it was a way to give voice, form, and spirit to a history that was lost to us.

My time studying with Myisha Priest in her course Women’s Textiles re-introduced me to the centuries-old quilting practices of African American and Black Diasporic communities in a more academic setting. Inspired by the ways in which quilts were and still are used as mediums for storytelling, especially during enslavement, I decided to create a quilt as a potential answer to my initial inquiries. My volcano quilt depicts a scene of La Soufrière’s 1812 eruption from the theoretical perspective of an enslaved St.Vincentian quilter. Of course, during this process, I was sensitive to my positionality as an African American in the present. It was not my wish to impose onto or reconstruct the archives, but rather to offer a possible addition to them. My project was an attempt to communicate with history and, hopefully, sew together any holes left by neglect.

Dr. Jazmin Scarlett was an incredible source for me during this process, and at the end of my project, I gave her the volcano quilt. When I gifted the piece, St. Vincent was going through a humanitarian crisis; La Soufrière had erupted again on the island, causing a massive panic among its people. I hoped that the comfort I found in piecing together this quilt could be felt by her in these moments of stress.

Volcano Quilting

In the year 1812, Saint Vincent’s Island, a then-British colony in the Caribbean Sea, braced itself against the power of a volcanic eruption. As black ash plumes drowned out the sun, many of the island’s inhabitants considered it to be the end of days, and within their hearts, a primal fear festered and burrowed itself deep. Standing in the presence of such a visceral phenomenon would certainly elicit feelings of despair, and possibly even those of awe. Renowned British artist J. M. W. Turner captured this historic event in his painting, The Eruption of the Soufrière Mountains in the Island of St Vincent, 30 April 1812 (1815). Turner presents La Soufrière in sublime, destructive glory, towering over the island as a few townsfolk, rendered minuscule in their rowboats, watch in still submission. And yet, missing from this dramatic image of eruption is the presence of a population who was weary and vulnerable far before danger exploded to the surface. If European colonists and mainlanders viewed this scene with terror and grim fascination, one has to wonder how a slave, with an already weathered mind and beaten body, may have reacted to such a display?

Under the cruel circumstances of enslavement, where willpower and self-agency is violently suppressed, a slave would have limited knowledge of the new world they were sold to. Before April 30th, 1812, St. Vincentian slaves may not have ever seen a volcanic eruption, and now they found themselves in the midst of an explosive one. To our misfortune, not much is known about the psychological effects that environmental disasters and natural hazards—hurricanes, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, droughts, etc.—have on enslaved populations in general, nor about those in nineteenth-century plantation economies in particular. While we can infer about their initial responses based on contemporary accounts from people faced with natural disasters, the full extent of their emotional reactions and coping processes are largely unknown. The historical archives documenting the 1812 eruption of La Soufrière neglect to include the slaves’ firsthand accounts; their voices are forgotten, and ultimately lost to time.1

However, contemplating what they might have experienced is not entirely futile, nor is its inquiry completely unanswerable. Looking at the creative practices of other African Diasporic communities during their periods of enslavement may help us examine how St. Vincentian slaves processed their environmental trauma. As such, this paper will consider the ways in which slaves, in the aftermath of the 1812 eruption, may have responded. One such possibility is through art-making, or more specifically, story and narrative quilting, a tradition that has deep cultural resonance for diasporic communities. As such, I propose that St. Vincentian slaves may have immersed themselves in quilt-making as an act of healing and comfort. For my own meditation on trauma-based art-making, I carefully engaged with the theoretical perspective of a St. Vincentian slave by crafting a story quilt of the volcanic eruption.

Before further exploration of this creative practice, it is best to ground the discussion of the 1812 eruption in its historical context. Saint Vincent is the largest member of St. Vincent and Grenadines, the Windward Island chain in the Southern Lesser Antilles region of the Caribbean. The island is known for its beautiful waters, lush mountains, and most famously, for its massive, active stratovolcano, La Soufrière. By 1812, the tumultuous oscillation between French and British colonization of the island had settled, with the British in power. At the time of the eruption, St. Vincent and the Grenadines had a total population of about 29,500 inhabitants of which 90.8% were enslaved African laborers. In time, the colony became an exceedingly profitable imperial sugar island, accounting for 7.8% of British West Indian cane production.2 Since permanent European settlement commenced on the island, the 1812 eruption was the first to be documented in detail. In his thorough examination of archival data, historian S.D. Smith (2011) assesses the susceptibility of a slave society to volcanic hazards. How vulnerable was plantation slavery and, more pertinently, enslaved Africans to La Soufrière’s destructive path?

When reviewing anecdotes and imaginings of La Soufrière, Smith found a common sentiment shared among the island’s inhabitants; to them, “the eruption was an exogenous occurrence, a calamity that no human could avert.”3 While a volcanic eruption is a horrific scene for many, Smith suggests that the overall magnitude of catastrophe was embellished by the British media at that time. Although the output losses are estimated at 14% of the island’s GDP, thankfully enough, the loss of life was minimal. Smith states that about ten slaves, fleeing from the Wallibu and Duvailles sugar mill estates, perished from the initial explosion.4 Furthermore, while a slave’s restricted mobility became a feature for plantation masters to brutally exploit, situating slaves in vulnerable, hazardous locations did not become common practice on St.Vincent until after 1812, during the island’s reconstructive period. The geographical decentralization and capital value of plantation slavery throughout the region seemingly sparred the population from facing the brunt of La Soufrière’s force. However, this is not a diminishment of the lives that were lost; if anything, the placement of slaves in safer locales was more than likely due to imperial self-interest. A major takeaway from these findings is that the hyperbolic characterization of the 1812 eruption is mostly a reflection of British anxiety over a loss of control and capital investment. What brings Britain unease, as depicted in Turner’s painting, is the symbol of imperial wealth confronting fiery, cataclysmic doom.

And yet, during these moments of crisis, where are the voices of the enslaved? In her thesis, Scarlett stresses the failure of scientific literature, stating that, “data collected for the 1812 and 1902-1903 eruptions of La Soufrière show that the colonial government, the colonists, British and American newspaper reports, and scientific fieldwork manipulated, minimized, or silenced the voices of the indigenous population, women, enslaved African/creole/freed persons and former indentured Portuguese and Indian communities.”5 As Scarlett and others theorists urge, by dismantling the falsehoods of Western thought, we begin the process of decolonizing science. With my quilting project, I hope to possibly aid in bridging the gaps of history by acknowledging the voices of the voiceless.

For centuries, quilt-making has been a traditional crafting practice for American, Native American, and—most relevant to our topic—African American and Black Diasporic communities. During the horrors of slavery, Black quiltmakers, who were primarily women, found solace in the practice. Lovingly, they gathered the worn, scrap fabrics of their domestic life and sewed together quilts of remembrance and warmth. And, as they touched and smelled the sentimental materials of their home, these women found a nurturing comfort in quilting. For them, the practice of quilting—and the song, dance, and poetry that surrounded this communal activity—were creative releases as much as they were means of therapy, survival, and political resistance. Using the richness of traditional African and African American imagery and folklore, the women told stories of family and friendship and of freedom and flight. Moreover, with bold, vibrant colors, the artists would sew symbolic characters, historical events, and even hidden messages into the fabrics.6 7 Black bodies, free and unbounded, flew and danced on the surfaces of these quilts; a kind of magic helped empower them to sanctuary. As described by Jason Young (2017), the Flying African motif found in folklore, “embodie[d] a kind of resistance par excellence by asserting that enslaved men and women were not ultimately bound to chain or shackle, but were instead free to challenge the constraints of slavery and the very limits of human capability.”8 For those who did not have a voice, quilt-making would speak for and with them.

A St.Vincentian slave who had experienced the shock of a volcanic eruption may have very well quilted as a way of navigating internal conflicts as well as conveying stories to future generations. With its therapeutic nature, quilting invited its creators to remember and sustain their own legacies. As such, I began the process of crafting a St.Vincentian volcano quilt that engages with Garifuna and African-American imagery, and commemorates the historical event. I looked to the beautiful works of Sarah Ann Wilson, an enslaved quiltmaker, and the contemporary African-American artists Faith Ringgold and Emma Amos for inspiration. Since quiltmakers would piece together fabrics from their everyday life, such as workwear clothes from loved ones, or old, worn blankets, I studied Robert S. DuPlessis’s detailed research on slave textile regimes (2012) to stay within the constraints of historical accuracy.

In his analysis of the dress of enslaved men and women in the French Antilles, DuPlessis found that slaves had access to two different types of textile regimes; one for the workday, and the other for special occasions, such as Sunday, holidays, and festivals. As seen in the visual representations of slave life, their basic work uniforms of rough linen and hempen adhered to a certain standardized homogeneity. Men wore knee-length culottes and drawers, and women short and long skirts or petticoats.9 For the more special days, this garment regime emphasized choice fabrics, like striped cotton or madras patterns, colorful adornment, jewelry, and, for women, massive headpieces of handkerchief. DuPlessis explains further,

Women put colored underskirts under fine white cotton or muslin overskirts, wore short jackets (corsets) that matched one of the skirts, sported bracelets, rings, necklaces and lace collars and sleeves, brilliant white lace headdresses. Men boasted wide, pleated skirt-like pants, over tight drawers, doublets over puffed out shirts, decorative silver buttons and colored stones, earrings, and hats.10

Furthermore, the work of Italian painter Agostino Brunias detailed the life and dress of enslaved and freed peoples in the French Caribbean extensively, albeit in a highly idyllic, romantic manner (his painting The Dance of the Handkerchief (1770-1780) and print Barbados Mulato Girl (c. 1764) provide examples). However, because of his decades-long, extended visits to the Caribbean, Brunias’s paintings were the best resource for me in terms of accurately depicting what types of fabrics and styles enslaved people wore.

Brunias’s artworks and DuPlessis’s research helped immensely during my quilting process. From here, I began to gather fabrics, such as rough linen, thin, striped cotton, and light felt, along with embroidery threads and stuffing to hand sew the surface of the quilt. For the colors, I used blue, indigo, red, dark, and light green fabrics with yellow, silver, and dark gray threading; not only were these shades featured prominently on St. Vincentian slaves, but they also hold significance culturally for the Garifuna and African Diasporic peoples as well. When I first began my project, I desired to contemplate the therapeutic art practices of enslaved St. Vincentians, but because of the island’s recent humanitarian crisis, it had become increasingly pertinent On April 9th, 2021, La Soufrière erupted explosively, causing thousands of people to evacuate the island. Thankfully, there was no immediate loss of human life due to eruption. However, the effects of such a disaster, such as mass displacement and infrastructural and agricultural devastation as well as Covid-19 are still impacting the island’s recovery about a year later.

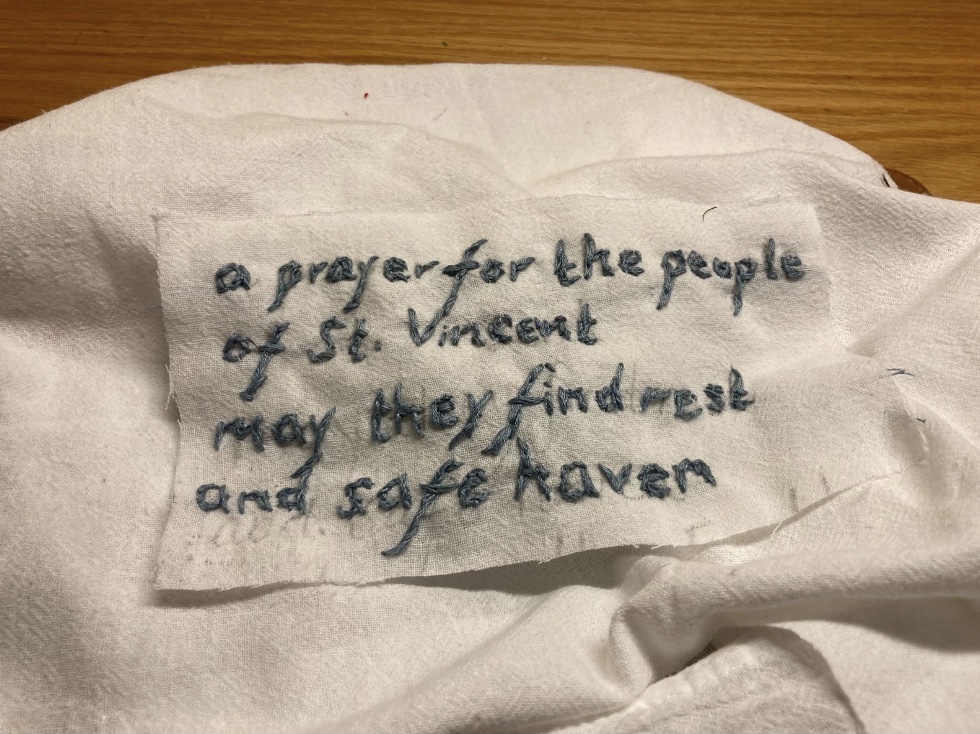

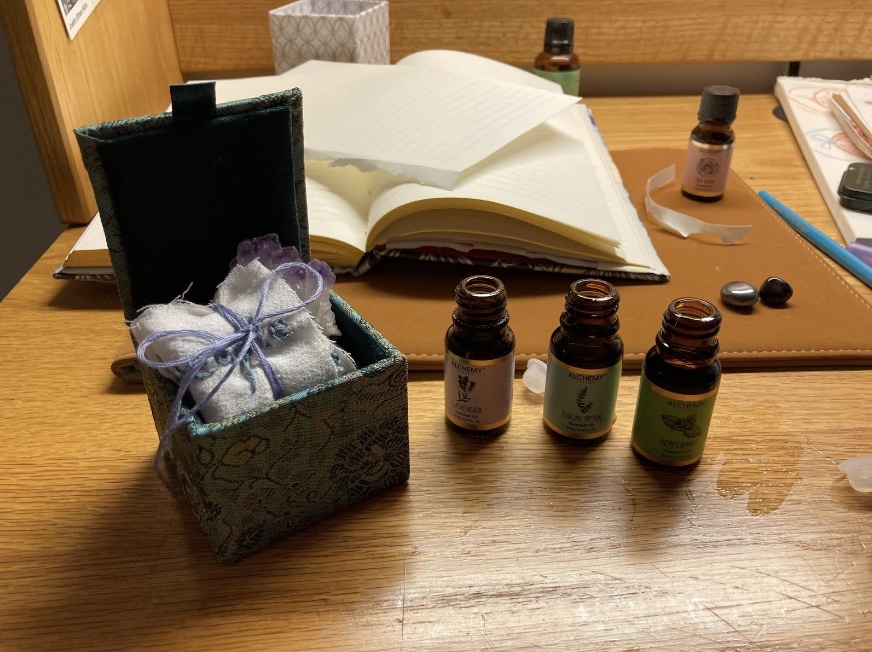

On the volcano quilt, are Black people in flight. In the midst of the eruption, they dance in midair together. Guided by their magic and faith, they move toward peace, safety, and heaven. In flight, they are free from the perilous black ash of La Soufrière and the bonds of enslavement. The people, hand-cut by myself from felt material, are dressed in the attire afforded to slaves of that time. They, along with the quilt in its entirety, are bathed in the scents of St. Vincent’s island: eucalyptus, lavender, and peppermint oils embodied the fragrances of the sea, the rainforest, and home.11 And, within the body of the quilt, is an embroidered prayer of my own that was warmed by close care and affection: A Prayer For the People of St.Vincent. May they find Rest and Safe Haven, and May the Earth be Still and Calm.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge and pray for the current humanitarian crisis of Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Special thank you to Dr. Jazmin Scarlett for her incredible help and insight during this project. I hope you like the quilt!

- From a detailed, firsthand pamphlet published by St. Vincentian printer J.T Calliard (testimony from Thursday, April, 30th, 1812): “Terror and Consternation now seized all Beholders…The Negroes became confused, forsook their work; looked up to the mountain, & as it shook, trembled, with the dread of what they could neither understand, or describe” (Smith, 61).

- S.D. Smith, “Volcanic Hazard in a Slave Society: The 1812 Eruption of Mount Soufrière in St. Vincent, Journal of Historical Geography 37, no. 1 (2011), 56-57.

- Smith, “Volcanic Hazard in a Slave Society,” 61.

- Smith, “Volcanic Hazard in a Slave Society,” 59.

- Scarlett et. al, “Coexisting with Volcanoes,” 58.

- Alana Butler, “Quiltmaking among African-American Women as a Pedagogy of Care, Empowerment, and Sisterhood,” Gender and Education 31, no. 5 (2019): 590-603.

- In her research on quilting practices of enslaved women, Alana Butler states that, “Complex quilt making patterns contained hidden codes that were instrumental for helping escaped slaves flee through the Underground Railroad and into Canada.”

- Jason R. Young, “All God’s Children Had Wings: The Flying African in History, Literature, and Lore,” Journal of Africana Religions 5, no. 1, (2017), 50.

- Robert DuPlessis, “What did Slaves Wear? Textile Regimes in the French Caribbean,” Dans Monde(s) 1 (2012), 180.

- DuPlessis, “What did Slaves Wear? Textile Regimes in the French Caribbean,” 182

- I asked Dr. Scarl to describe how St. Vincent itself smelled. By doing so, I wanted the quilt to embody the same sensory experience of the island.