In conveying scenes that the viewers can possibly see themselves in, the distance between viewer and faraway conflict lessens.

What Does Violence Look Like?

Photographing the Colombian Conflict

Photography has the ability to bring out emotions in the viewer, provide documented evidence, and tell a story—and thus, it is one of the most effective methods of depicting war, in its ability to do all these things all while immortalizing a single moment in time. As Susan Sontag writes in Regarding the Pain of Others, “the photograph has the deeper bite [compared to film]. Memory freeze-frames; its basic unit is the single image. In an era of information overload, the photograph provides a quick way of apprehending something and a compact form for memorizing it.”1 Given the photographic image’s ability to leave a stamp on the memory of the viewer, photography has become a tool in war, used by both outsiders and citizens in order to impact public opinion. But the power of photography, along with its limitations, presents more than one complication for the conflict photographer when the war they are photographing is incredibly complex and scenes of extreme violence are commonplace and woven into the fabric of citizens’ daily lives. Such is the case with the Colombian civil conflict, which occurred from the mid-1960s up until an official ceasefire in 2016—though, many would argue, the violence is far from over.

What does conflict photography look like when the effects of decades-long violence have embedded themselves in the peoples’ way of life—and those people are both united and separated in their experiences? Further, how does one go about conveying this kind of conflict to those separated from it in the most effective and accurate way? These questions seem especially pertinent to Colombia, where war manifests in many different ways and is hardly as simple as one group versus another, or acts of blatant violence between opposing groups—though, of course, those do exist and must be documented as well. Thus, this means that photographing Colombia is hardly clear-cut; it is the job of the conflict photographer to reconsider their own conceptions of what war looks like, take the time to understand the conflict from the perspective of the citizens, and not allow their own preconceptions to influence the subjects they chose to photograph and how they go about depicting those subjects. These questions must be considered carefully: Photographs themselves have the potential to wage intentional or unintentional violence, after all. A careless photograph risks perpetuating harmful stereotypes about a region or separating viewers further from the conflict, making them look away rather than look closer.

An accurate visual depiction of Colombian civilians, guerilla groups, and more must balance sensational images focused on intense turmoil and acts of inhumanity—which have become standardized in the language of war—with those less centered on spectacle. In order to make the most change, and combat the surface-level assumptions of what war looks like, more casual day-to-day images must be circulated just as much as those that depict extreme suffering—but they also must not diminish or trivialize the violent reality that many Colombians do face. It’s a difficult balance to achieve, but a necessary one to attempt. In this essay, I will analyze a body of work—Álvaro Ybarra Zavala’s Macondo—that does this well and expands our understanding of war and makes the conflict more “real” for the viewer.

First, it is important to describe the history and context of the Colombian civil conflict—similarly, it is important for the photographer, especially if they are not a citizen who has experienced the conflict firsthand, to understand what they are photographing in order to produce the most accurate and empathetic photographs. Though there are many more internal and external factors than I am able to address in this paper, the major developments of the conflict throughout the decades give an illuminating background to the photographs I will analyze. Preceding the conflict’s start, there was a bloody period known as La Violencia from 1948 to 1958, during which the landowning elite organized the killing of over two-hundred thousand peasants and displacement of over two million others. In 1958, the two parties agreed to end the fighting and excluded any other parties from the political system, which set the stage for the emergence of communist, leftist guerilla groups, the most prominent being the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN) in the mid-1960s. Both groups claim to represent the rural poor, use violence, kidnappings, and extortion for leverage and income, and aim to overthrow the government and achieve social and political change. The conflict has been fueled throughout the decades by other domestic and international factors: Starting in the 1980s and continuing to the present day, the drug trade exacerbated the violence, as well as the establishment of right-wing paramilitary groups (which were linked to the state military as well as drug cartels) that emerged as landowners organized to protect themselves. In the 1990s, the cocaine trade continued and was connected to both leftist guerillas and far-right paramilitaries, heightening political tension, economic imbalance, and displacement, while thousands of small farmers changed over to producing the illicit coca crop. In 2002, Colombian politician Álvaro Uribe received support for opposing armed groups, particularly leftist guerillas, and during his presidency, militarization intensified and his administration was suspected of human rights violations. The civilian population was increasingly drawn into the armed conflict. Thus, the violence continued on all sides, waged by the state, paramilitaries, and guerillas. Peace talks started on and off again throughout the decades, but fell through until 2016 when Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos signed a definitive ceasefire and disarmament agreement with the FARC. By that time, over 220,000 people had died, five million had been displaced, and eight thousand minors had disappeared during the conflict.

With so many factors and intricacies involved, even the exercise of attempting to describe the conflict via written language perhaps demonstrates why conflict photojournalism is so integral in really getting at the realities of the Colombian people. Language just puts words to a people and their circumstances, giving abstract shape to them and allowing for some degree of separation, whereas photographs give a face to them. Not to say photography doesn’t have its own pitfalls — since many presume photography automatically equals truth, the medium also has the greatest capacity for masking or skewing those realities as well. Photographs are not mimetic of reality or the equivalent of absolute truth: Authors Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright write in Practices of Looking that “systems of representation do not reflect an already existing reality so much as they organize, construct, and mediate our understanding of reality, emotion, and imagination.”2 How close can we actually get to portraying the truth of a conflict or the reality of violence through photography, then, if the photographer constructs our understanding of the subject matter? To what extent have other images of conflict created a standardized, almost mythologized language around conflict, and how much does the photographer have to conform to that language to make a difference and leave an impact on the viewer? Spanish photographer Álvaro Ybarra Zavala’s years-long project Macondo: Memories of the Colombian Conflict provides an alternative approach to the standardized visual language around war, while also not masking the damage and suffering inflicted by the conflict. In doing so, his work provides a valuable framework for other conflict photographers. It’s worth mentioning that I’m examining a collection of works, rather than an individual photograph, because I believe that a body of work most often gets the closest to leaving the viewer with an accurate perception of a conflict. The photographs in conversation provide the most insight into what conflict looks like and also make the most impact on the viewer, making the conflict more immediate to the outside viewer and engaging them in the act of bearing witness.

Regarding the standardized photographic language around conflict that Macando is subverting, it is not difficult to trace the link between shock value and what images are chosen to be circulated in western media. In “Peace Journalism: A Paradigm Shift in Traditional Media Approach,” author Rukhsana Aslam describes how many media professionals and audiences have noticed that there is “‘something seriously wrong’ with contemporary media coverage of war and conflicts.”3 Aslam describes how one journalist believes the root of the problem to be tight deadlines, which discourages in-depth reporting; academic Mosese Waqa thinks the notion that “conflict sells” is responsible for standard war coverage4. Money, though, is hardly the only factor in perpetuating this standardized idea of what war should look like in the media—many likely stick with the conventions of conflict photography because there are certainly instances in which it has made an impact on viewers historically. For one, Nick Ut’s 1972 photograph of a Vietnamese girl in pain and running naked down a road following a napalm attack changed the American perception of the Vietnam War. But over time, as media has become more image-saturated and therefore also violence-saturated; many media professionals who have personally witnessed conflicts “have found the traditional media approach lacking, both in terms of bringing a better understanding to the people about conflicts through comprehensive stories and in creating impact on the key players to want to do something about it.”5

Ybarra Zavala first traveled to Colombia around 2003. It’s worth noting that he wasn’t on assignment, so he didn’t have the pressure of a publication with a “conflict sells” mentality or a non-governmental organization wanting photographs to encourage donations. He spent over a decade in the country, embedding himself in the communities he photographed, and he felt a connection to the region because of his childhood, during which he saw his neighbors become ravaged by heroin addiction.6 He saw a similar degree of “self-destruction” in both cases. The personal element of Ybarra Zavala’s work complicates the traditional notion that conflict journalists must be a fly on the wall in order for their images to be representative of the truth: Ybarra Zavala demonstrates that images become more truthful when photographers are or attempt to become insiders and get the reality of the situation from the people themselves, by living with them. This comes across in his images of guerilla groups, who allowed him to live with them in their camps six times. While photographing different regions in Colombia, he also noticed the disconnect between groups in different areas who were experiencing the conflict in different ways. This realization likely wouldn’t have come to a photographer who was only visiting; in contrast, Ybarra Zavala was embedded in the communities and had become familiar with his subjects. In his body of work, which explores the guerillas, the drug trade, displacement, missing persons, and more, Ybarra Zavala creates images that complicate the viewer’s understanding of the conflict and shows how differently it is experienced between people and regions. For one, he incorporates images devoid of obvious visual violence, such as in a 2016 photograph that shows a smiling group watching guerrillas play soccer with civilians from Robles, Cauca. The caption in Macondo elaborates: “In these regions, the total absence of the State made the FARC-EP the only authority. The problems and disputes of the community are resolved by the guerrillas. In communities like Robles, the family and affective bond between the guerrillas and the civilian population is very strong.”7

In this single work that emphasizes the emotions on the faces of the citizens, Ybarra Zavala goes about showing the separation between regions and the multifaceted nature of the conflict by depicting a subject that many would not consider a part of Colombia’s conflict. He shows the conflict by going beyond violence, which serves to draw the viewer in just as much as an image of extreme turmoil. “The gruesome invites us to be either spectators or cowards, unable to look,” Sontag writes.8 But an image such as the one above only invites spectatorship, and thus makes the conflict more real, less unbelievable, for the viewer. In fact, in this image being paired with others that do show violence, it manages to evoke a different kind of shock value in its unexpectedness, subverting our idea of what conflict looks like; “for photographs to accuse, and possibly to alter conduct, they must shock,” and this photograph does have the capacity to alter conduct in showing a different side to FARC.9 This shock, instead of being achieved by gruesomeness—which has traditionally been achieved by showing dead bodies or people fleeing for their lives—is induced by the fact that it goes against the common misconception in the media that the FARC is all bad, all the time—a narrative that is in fact pushed by the state. These kinds of images also serve to ground us, and bring us back to a more familiar reality and prepare us to view the less familiar, extreme suffering, such as the photograph that comes a few pages later of a pregnant woman who was murdered along with her family in 2009, though whether by the state or the FARC is unclear.

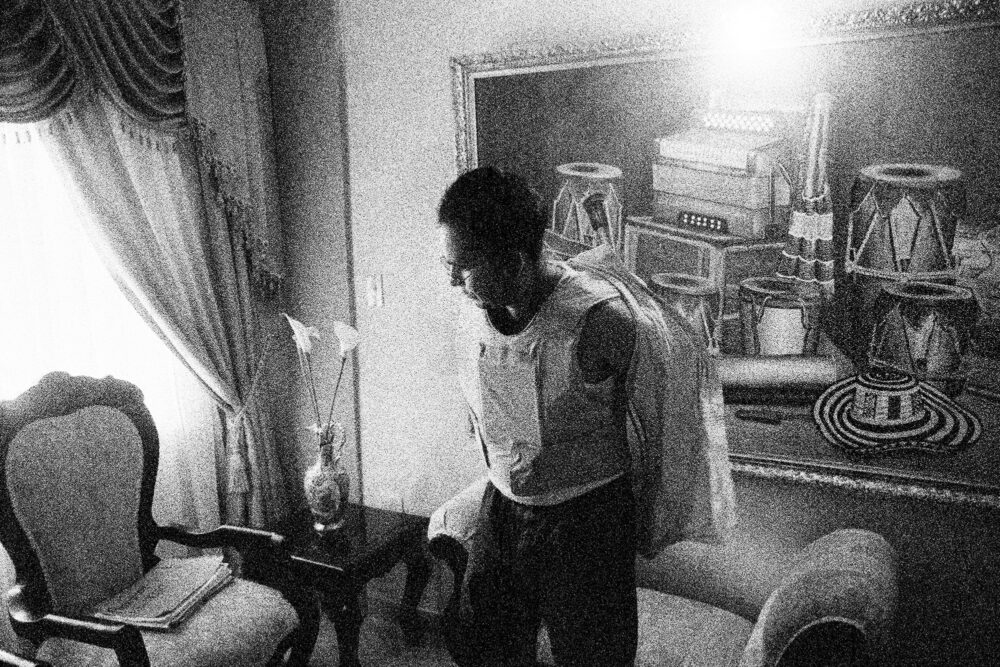

As much as the photographs impact the viewer on their own, as a body of work, they are more effective in stirring the viewer—the photographs of suffering and violence are more powerful when placed in conversation with the images that show a less violent day-to-day. However, American photographer Stephen Ferry, who has lived in Colombia since 2000 and produced photography book that focuses on “human rights and the struggle of Colombian civilians to resist the violence,” manages to capture both of these things—the devastation and the more relatable, less violent—in a single image, echoing the juxtaposition found across Ybarra Zavala’s body of work. The image, taken in 2009, shows doctor Juan David Díaz preparing to remove his bulletproof vest upon returning from work at a local hospital in Sincelejo, Sucre.

The image is far from sensational; it’s quiet and casual in how it goes about conveying the level of violence that has embedded itself in Colombians’ way of life, but it is shocking in how the photograph shows violence seeping into the privacy of home. It’s inescapable. This photograph, as compared to the ones included by Ybarra Zavala as well as many other images of conflict, could also hardly be used by one side or the other as propaganda. Sontag describes this phenomenon in Regarding the Pain of Others with the example of how during the Bosnian War, Serb and Croat propaganda briefings used the same images of children killed in the shelling of a village. Extreme images invite polarization; they also invite less analysis, more manipulation, and a shorter viewing time. The viewer is either desensitized to the violence and just moves onto the next thing, is overwhelmed so that they look away, or perhaps doesn’t wish to be triggered or re-traumatized and so avoid looking. These images are important to include in the documentation of a conflict, but they must be placed in conversation with those that are less sensational in order to depict the most accurate version of events—and also in order to connect the outside viewer to a distant conflict. Both kinds of images show violence, and the ones less centered on spectacle serve to complicate the viewer’s idea of what violence and conflict looks like. In conveying scenes that the viewers can possibly see themselves in, the distance between viewer and faraway conflict lessens. They become more engaged spectators, encouraged to look deeper, rather than look away, overwhelmed and helpless.

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (Penguin Books, 2005).

- Marita Struken and Lisa Cartwright, Practices of Looking: An Introduction to Visual Culture (Oxford University Press, New York, 2018), 13.

- Rukhsana Aslam, “Peace Journalism: A Paradigm Shift in Traditional Media Approach,” Pacific Journalism Review 17, no. 1 (March 2011), 120.

- Aslam, “Peace Journalism,” 120.

- Aslam, “Peace Journalism,” 121.

- Gonzalez, David. “Looking at All Sides in Colombia’s Conflict.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 27 Feb. 2017.

- Álvaro Ybarra Zavala, Macondo, Memories of the Colombian Conflict, 2016.

- Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others.

- Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others.