On the spirit of youth and Didion’s New York City.

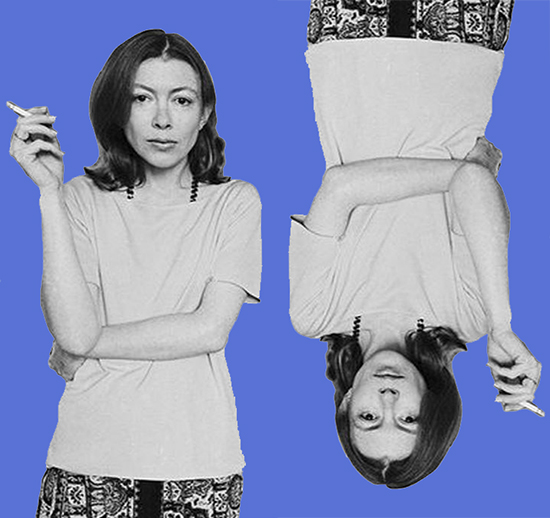

Coming of Age: Joan Didion

The Spirit of Youth

“I was in love with New York. I do not mean ‘love’ in any colloquial way, I mean that I was in love with the city, the way you love the first person who ever touches you and you never love anyone quite that way again.”—Joan Didion, in “Goodbye to All That” (1967)

A few weekends ago, I did the thing New Yorkers do. After a day in the office of my editorial internship, I walked over to Trader Joe’s to pick up almond milk, herbed popcorn, and clementines (since I wanted to be healthy), went back to my place to heat up a quick snack and relax, got a call from the friend I was later meeting that she’d just left her internship and was “on the way.” I got ready in a haze of LUSH perfume, velvet, and The Helio Sequence looping effervescently in my head and took the Downtown 6 to Spring Street for our eight o’clock dinner reservation at a restaurant that had “$$$” next to its name on Yelp—I knew this would mean an imminent monetary sacrifice, but it was Friday night and the boots I was wearing clacked against the pavement in a way that never fails to fill me with the belief that the world is mine for the taking.

Amidst belly-aching laughter, we talked fashion, school, our dreams, and everything in between. Soon, we started on boys—those in our lives and those in general. We were considering our day-to-day schedules in the scheme of dating, and after having just told a boy I was talking to that I just wanted to be friends a few days prior, I dramatically recalled, in more or less words, the feeling that followed:

“Jokingly, the thought used to occur to me of falling into the archetype of the go-getter career woman who loves her work but falls short in love . . . But after sending that text and mulling over the refreshingly understanding response that followed, the thought grew more vivid with an increasing shade of possibility.”

This led into a discussion about the concept of “having it all,” a phrase that takes root in my mind after years of Sex and The City marathons and lazy summer afternoons watching daytime talk shows. I have this thing where I categorize moments such as sitting on a park bench in Brooklyn with friends on a sunny day, taking an easy stroll through the West Village, infected with the contagious smiles of the kids on nearby playgrounds, eating greasy pizza on stoops of ritzy brownstones, dancing with friends under disco balls at bougie art parties as moments in which I feel “so New York”—as if for the duration of the moment, mortality seems to become a myth. And this was one of them. I’m a girl from the Deep South where we eat dinner at 5:00 p.m., and “Subway” is where you go once a month because you want to be healthy. I’m a girl from a place where my days were open to feeling the sun and daydreaming, brimming with—and sometimes frustrated by—the overwhelming sense of being forever sixteen, enchanted by all the possibilities I watched, read, and heard could lie beyond. So fast-forward back to the present moment in this cozy restaurant that serves kale salads with mint leaves, and us studying the drinks menu like naturally we were going to order something from it. It was here that nineteen suddenly felt thirty and “so New York.”

Hours later, after midnight, we’d find ourselves twelve years old in Little Italy, screaming over Justin and Selena getting back together over chocolate cake and cannoli.

*

You may know her from her widely acclaimed novels, such as Plays As It Lays, and essay collections, such as The White Album, or you may recognize her from the iconic Spring/Summer 2015 Celine campaign ad shot by Juergen Teller that captures an older woman in a sleek silver bob, oversized pitch-black sunglasses, and a quintessential black dress on the couch of her Upper East Side apartment—a striking contribution to the shattering of the notion that beauty and style are contingent upon age, and an assertion that youth is not ephemeral. Through her poignant memoirs and journalistic novels, Joan Didion, one of the great literary and fashion icons of our time, has taken readers through pivotal points of her life such as her first job writing sociopolitical pieces at Vogue, her marriage to her late husband John, the adoption of their daughter Quintana, their days as a family in the crux of the sex, drugs, and partying of 1960s California Rock ‘n’ Roll, the peace they later found in Malibu, and the passing of both her husband and daughter, two years apart.

In Joan Didion: The Center Will Not Hold, the 2017 Netflix documentary about the iconic writer’s life, Joan illuminates a spirit of youth that is neither fixed nor defined by age or behavior. And neither is it just some idyllic, bubblegum pop, braces-clad state of being. She brings us from being a child in her native home of California who couldn’t stop telling stories to her years dealing with nervous breakdowns and depression. She looks back on the grief she’s experienced throughout her life, grief she learned to cope with by writing landmark novels such as The Year of Magical Thinking, the book she wrote following the sudden death of her husband John, and Blue Nights, Didion’s self-admitted most difficult novel to write as it delves into the grief and emotional emptiness she faces following the death of her daughter Quintana. In Blue Nights, Didion also touches on her own complex relationship with aging, for her daughter’s death is ultimately what forces her to confront the inevitable passage of time and to admit to her meager appreciation of the moments with her daughter when she had them. It’s like every time an elder knowingly tells you to “enjoy your youth”: You humbly smile with a respectful nod but you don’t quite understand what they mean until life hits you with those moments that strip the sheen off of the world and lend the feeling of uninhibited youth a newfound connotation of being something forever fixed in the past.

But it doesn’t always have to be.

Toward the end of that “so-New-York” night, my friend and I stumbled back uptown, intoxicated by the indescribable magic of feeling older than we actually were yet existing in a state of youth that, despite being conscious of the progression of time and growing older with each passing second, feels like every day you’re eight and it’s Christmas morning. It’s a romance that Didion knows all too well. In her famed 1967 essay “Goodbye to All That,” she writes with eloquence and honesty about her multi-faceted love affair with the city. “New York was no mere city,” she writes. “It was instead an infinitely romantic notion, the mysterious nexus of all love and money and power, the shining and perishable dream itself.”1 Perishable because, as Didion later confesses, she began to lose her affinity for New York. Instead she became captivated by the conviction that all to be seen in New York was already seen and that all to be heard was already heard. Feeling the weight of “how bad things got” when she was twenty-eight, how she hurt those close and distant to her, and how mentally, she was spiraling towards some unknown direction, she concludes in the essay that “New York is, at least for those of us who came there from somewhere else, a city only for the very young.”2 It is here that Didion implies that youth is not bound by numerics or time but a feeling—despite being twenty-eight in this time of her life she is describing, the luster she once possessed by living in New York significantly dulled. “I was very young in New York,” she wistfully recollects, “and at some point, the golden rhythm was broken, and I am not that young anymore.”3 Feeling as if she had finally stayed “too long at the fair,” Didion left New York behind for California in 1964.4

In 1968, after long since having made the nostalgic return back West, Didion published Slouching Towards Bethlehem, a collection of essays detailing her experiences and emotions in the California of this new chapter of her life. “It is hard to find California now,” she declared. “Unsettling to wonder how much of it was merely imagined or improvised; melancholy to realise how much of anyone’s memory is no true memory at all but only the traces of someone else’s memory.”5 What began as a journey to reconnect with herself and to simply experience life more authentically by going back to California turned into wonderment as to what direction her spirit was trying to take her.

As Didion voices it in Goodbye to All That, New York is a city for only the very rich, the very poor, but also for only the very young. And after a twenty-four-year absence, Joan Didion would later find herself swept back to New York, “a city for the very young,” where she still lives today at the ever-vibrant age of eighty-three.