When my dad lived in Indianapolis, it felt like we were free.

Family Visit: The Hits

When my dad lived in Indianapolis, it felt like we were free. I didn’t live with him anymore so when I visited him, it was a break from home—and we treated it as such. My mom would bemoan having to get me “back on track” when I returned to her, a dramatic way of complaining that I had a newfound expectation of a midnight bedtime.

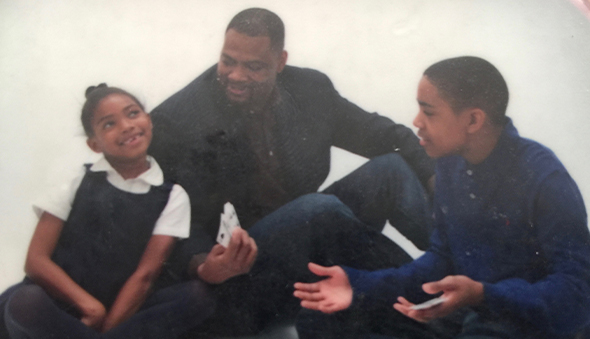

These visits were especially fun when my brother was with us. We came from two coasts—New York and Miami—just to be together. It felt like an event that we three Joneses were all in the same place at the same time and, really, it was. There aren’t usually that many of us in one place. My dad certainly thought of it as an event, a break from reality; he’d often lean back in his seat (any seat), smile and, in a severely broken accent, say Mi Familia! There was a lightness about him, a sense of freedom that was palpable, even to me at nine years old. Now that we were together, we could do anything we wanted. We could go anywhere. We rarely did, but we could.

I was never sure why, but my dad seemed to love having us in the car with him. A black Kia sedan was our steed. The drive, whether to Costco or Chicago, was always the highlight. An aux cord and a captive audience: this was all my dad needed to be happy.

Justin—Justy, ten years ago (and sometimes today)—would fold his knees to sit in the backseat with me, no matter how tall he got. This was our personal haven. It was the two of us. We were each other’s best audience, between the shared looks and tired jokes and nervy snickers (cheekily secretive at best, outright ridiculous at worst). My dad joked that he was our chauffeur, but I knew why my brother chose his seat: he knew where the party was.

Let’s be clear: the car was no democracy. Lamont—DJ Big Dawg— controlled the music, claiming driver’s privilege, and conveniently couldn’t hear requests when asked. I groaned at the beginning of each song, begging for the next to be “anything by Taylor” (Ms. Swift and I were, at this point, on a first-name basis).

“Party in the U.S.A.” (Miley Cyrus) &

“Sunday Morning” (Maroon 5)

But he always started out strong—maybe not Taylor right off the bat, but Miley at the very least. He appealed to his children’s demonstrably superior tastes in music, claiming that he “took himself by surprise” by loving whatever pop hits he knew we liked. (I didn’t let him fool me; we all knew he liked “Party in the U.S.A.” even more than I did.)

With the dated Kia dashboard as his mixer, DJ the Big Dawg set off to work: playing songs, skipping songs, going back 30 seconds, (getting distracted and making three or four consecutive wrong turns), turning the volume down on songs to talk over them, turning the volume up to help us hear hidden harmonies, (“Son! Did we just drive down this street?”), cutting the volume at the last second as a censor, (“Fuck! That was my turn!”), hitting the steering wheel to the beat, singing his heart out (sometimes off-key, mostly on). But most of these theatrics were for later. In the beginning, it was all about the joy. The fun. The car was bumping, we were dancing, we were together.

“We Belong Together” (Mariah Carey) &

“Bleeding Love” (Leona Lewis)

(Clap. Stomp. Clap-clap. Stomp. Clap. Stomp. Clap-clap. Stomp.)

Make no mistake: my dad’s music taste is not my music taste. Not at all. Any overlap in our playlists is a result of him recognizing that the music I like is great, not the other way around.

And yet… There are those songs, those certain songs, that are just embedded in my DNA. When they start, I can’t help but jam, the same way we used to in the car.

(Clap. Stomp. Clap-clap. Stomp. Clap. Stomp. Clap-clap. Stomp.)

It didn’t matter what we were doing: talking, arguing, laughing, eating, looking at the GPS—when that song started, we dropped everything and

(Clap. Stomp. Clap-clap. Stomp. Clap. Stomp. Clap-clap. Stomp.)

together, in unison, without a second thought.

I didn’t like this section of his playlists. The “downer” songs. The ones that my dad would say ooze soul. Give me more parties in America, less contemplations on lost love. I decided, because of these songs I was determined not to like, I wasn’t a romantic—which anyone who declares that they’re not a romantic will tell you is not true.

No, maybe I didn’t like Black music—not that I would have recognized this or, if I had, admitted it. But maybe that’s closer to the truth.

My brother seemed okay with it all. Maybe his taste just comes closer to my dad’s than mine ever will. Maybe he was nursing some 16-year-old’s lost love I’ll never know about.

“Having a Party” (Sam Cooke)

Sam was the raison d’etre of my dad’s playlists. Sam—you’ll notice the first name basis—is my dad’s all-timer, the definition of the voice of heaven for him. It’s kind of sweet how much my dad feels Sam.

Sam’s voice is as smooth as butter. Pure. He sings about loving a girl, asking her to dance with him and living happily ever after. It’s simple. Sam and Lamont are separated by distance and experience—not to mention years and years—but as soon as that music starts, they’re somehow the same.

I imagine my dad, escaping his brothers to find a moment of solace from his brothers in his childhood house—if it could even be called a house—listening to Sam and imagining that beautiful simplicity. The pure, simple joy of just having a party.

“Empire State of Mind” (Jay-Z and Alicia Keys) &

“Miami” (Will Smith)

I know it’s kind of on the nose, but these were absolute essentials. We knew approximately none of the words—these guys rap too fast—but it was never about the actual song. It was about the city. Justy and I lived in the two best places on Earth, I figured. We deserved to celebrate this.

I got a real kick out of being from somewhere they wrote songs about. (I suppose I would have to listen to country music to get that effect now. This is a line I would not cross.) My time in Miami was my prime, for the song if nothing else—even if the New York song always struck me as a little more flattering. (Will seems to think spending “a few days” in Miami is a compliment; I’m more attuned to Jay’s ride or die sentiment with New York.)

“Valerie” (Mark Ronson feat. Amy Winehouse)

Amy: Did you get a good law-yeh-uh-uh?

Justy: Aliya, can you say law-yeh-uh-uh?

Listening to “Valerie” means hearing how my brother put me into the song, how he made it mine. He has a knack for eliciting little giggles that stick with you—quips, jokes, puns. He uses his gift for love; he gifted me my own moment in one of my favorite songs.

Amy was my version of the voice of an angel. At nine, I was always confused (read: angry) about why she wasn’t the sole credited artist on this track. Sure, Ronson’s version of the song is what we always listened to, but Amy is clearly the singer and the reason to listen to this song.

These were my feminist roots, probably.

“All Falls Down” (Kanye West feat. Syleena Johnson)

I know, I know. Kanye is not it, but before he was said slavery was a choice, he was a great artist (still is? I don’t know, I don’t listen anymore).

My dad would have to censor this song half to death, typically skipping it before the third verse (not that it mattered because I had no idea what Mr. West was saying anyway). I teased him about insisting on putting it on the playlist if he was just going to skip half of it. He chuckled.

But I do remember one time—just once—when he let the song play all the way through. He turned the volume up and told us that there’s some truth to what Kanye was saying:

We tryna buy back our 40 acres

And for that paper, look how low we’ll stoop

Even if you in a Benz, you still a nigga in a coupe

and

Drug dealer buy Jordan, crackhead buy crack

And the white man get paid off of all of that

I didn’t get it.

“Fast Car” (Tracy Chapman)

In the car with my dad and my brother, I was free. We listened to music that had cuss words. We ate terribly (my dad stored a huge tub of Garrett popcorn in his car, and made near-constant stops at Mickey D’s for a large sweet iced tea, extra sugar on the side). The three of us together was the most family I’d experience in one place at one time between 2009 and 2012. But it was a happy time.

But of course, this was not the whole story. Here is the story:

After the divorce, my dad experienced a period of despair. Despair. There’s no other word for it. His worst day of independence was the first: driving home from the courthouse in Colorado, when he broke down in tears that made his sobs echo and his vision a kaleidoscope. He was behind the wheel of that Kia. He would never be able to shake that day from that car.

He moved to Indianapolis, where he thought he could be free. Independent and self-sufficient. It might have worked, if not for money. More accurately, if not for all the flights and hotels in New York and Miami. He was not going to be the absent father, but he had moments where he wondered if that Kia was all he’d have left. He wondered if he should move to China, just to get cheap work for a few years, get back on his feet. He decided he couldn’t live that far from his kids—his family.

Our times in that Kia were undoubtedly a lifeline for him.

I figured I knew why he made his playlists the way he did. They were, after all, the same: named for the occasion and date (think: “Family Visit, 2010”) and comprised of shuffled variations on his usual. His music taste was developed and unflinching: Sam Cooke’s entire discography, an odd variety of his old standbys, and whatever pop hit he used to reel us in.

I thought he listened to Mariah to get us to stomp and clap with him. I thought Sam just gave him a sense of comfort from when he was a boy. I thought he liked Kanye’s flow, since God knows I had no idea what he was saying.

But maybe not. Maybe he listened to Leona because she spoke some truth he hadn’t even come to terms with within himself. Maybe he listened to Jay and Will for the same reason he took an apartment between New York and Miami streets—to feel close to his children in some grand sense. Maybe he listened to Tracy because there was a time, long before all this, when his life was as simple as getting a fast car to keep on driving, away and away to a different life.

“Hey Ya!” (Outkast)

Or maybe it was all about the mood, the party of it all. Maybe it was just about loving the things he loved with the people he loved.

Whatever it was, these were good times. Great times. The best I’ve ever had with him.

I don’t know when my dad was happiest—I’ve never asked him. I think he’d say his wedding (to which I’d say which one, and he’d give me a look). Or maybe he’s latched onto one of the times we’ve replicated those times in the car, now in a Benz with me sneaking an AirPod into one ear and my brother silently rehearsing lines, but with Stacy by his side.

His time in Indianapolis—our time—probably wouldn’t cross his mind.