My own personal, seemingly insurmountable dragon was metaphorical Grief, it was now a part of me, and I couldn’t imagine a world where I would be able to domesticate the vicious pain.

How I Trained My Dragon

Over the past three years, I have become an avid connoisseur of children’s entertainment. Growing up, I loved the standard Disney fare and most of Miyazaki’s milder films, but I began distancing myself from kid’s content at seven or eight years old in an attempt to match the interests of my older brother, Reed. Even at ten, Reed liked dirty comedies and video games and loud action movies, and my affinity for Barbie: Swan Lake (2003) never stood a chance when it came time to share the remote. I was nine years old the first time I saw gore and torture on screen after walking in on him sneakily screening Saw (2004) in our dark living room late one night. If we ever decided to play together, I often found myself uncomfortably sprawled on Reed’s twin bed as he played Grand Theft Auto: Vice City in front of me for hours (“It would take too long to teach you”; “You’ll ruin my streak”; “Just be quiet and watch”). I’ve never liked feeling excluded or inferior, so I decided to push my boundaries and expand my palate, watching Good Will Hunting (1997) and Fight Club (1999) and every Will Ferrell movie ever in an attempt to make up for whatever I was lacking. I decided to grow up fast, at least in front of him, and kept the screenings of The Princess Diaries (2001) for nights alone in my room with a thirteen-inch portable DVD player.

A few nights ago, I found myself in a familiar position—nestled in a large, dingy couch, feet up on the coffee table, drinking beer, and leisurely scrolling through Netflix with my roommate, Corey. He wanted to watch Upgrade (2018), a gritty sci-fi action film. I wanted to watch, and make fun of, You Can’t Fight Christmas (2017), a mindless holiday romance. We kept scrolling and, eventually, he stopped at Kung Fu Panda (2008) and excitedly anticipated my approval—

“Eh, probably not.”

“Ally, whyyyyyy? It’s basically the story of your life.”

“I’m an orphaned giant panda destined to become a Kung Fu master and savior?”

“Yeah, loosely.”

Outside of my love of rice and abject clumsiness, Corey’s theory is flawed, but I hesitate to call it fully misguided. I have often found myself relating to heroic, magical tales and childlike quests over the past three years. I map my traumatic milestones alongside Harry Potter and Matilda and Nemo and escape into their shared naïve optimism and personal triumphs. Kung Fu Panda may not be my story, but if one animated kid’s movie does reflect my experience on this planet, it might just be one about a young boy and his dragon.

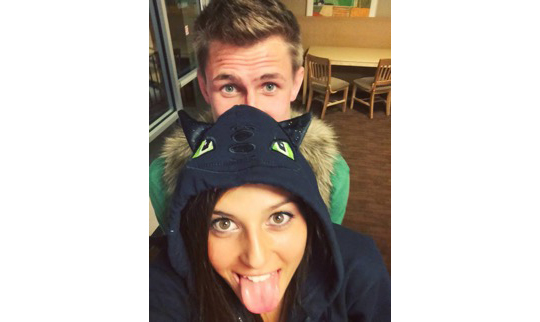

I had never paid much mind to DreamWorks’ How to Train Your Dragon (2010), directed by Chris Sanders and Dean DeBlois, until late 2015. I remember noting its Oscar nomination for Best Animated Feature and casually wanting to see it, eventually, but it never quite drew me in. Fresh out of my freshman year at NYU, I was in the height of my film-snob-phase and prioritized dark, mature movies over anything fun and young. It was only after my brother died in a car accident that I found myself grasping at the comfort films I had denied myself for so long. In the weeks following the memorial, I remembered that Reed had loved How to Train Your Dragon when I came upon a picture of him dressed as the main character that past Halloween. I figured that it might be a welcome addition to my growing collection of simple, childish movies that soothed me and watched the film later that night.

How to Train Your Dragon follows the young Viking Hiccup (Jay Baruchel) and his relationship with a rare and dangerous Night Fury named Toothless. Hiccup comes from Berk, an island ravished by looting dragons like Toothless, its citizens hellbent on destroying the species at all costs. After miraculously shooting down a dragon during an attack for the first time, a scrawny and sensitive Hiccup tracks down his prey and finds an injured, flightless Toothless. He immediately bonds with the dragon’s pain and humanity—a revolutionary act in his tribe. Hiccup is morally unable to kill Toothless, instead choosing to release him from the net entangling his body so that he can return to the maimed and grounded dragon in the future, study him, and understand more about the rare and surprisingly intelligent creature. Over time, and in a stunning montage of scenes showing their slow, playful bonding, Hiccup and Toothless begin to trust one another as Hiccup trains the dragon and manufactures a prosthetic to allow him to fly again. In sweeping, heavenly scenes, Hiccup mounts Toothless and the two soar together through the clouds as John Powell’s striking score swells and I’m brought to tears. The awe and freedom captured during these moments mimic the exact relief I craved in the nights following Reed’s passing. The victorious celebration of conquering one’s biggest challenge simultaneously comforted and depressed me. My own personal, seemingly insurmountable dragon was metaphorical Grief, it was now a part of me, and I couldn’t imagine a world where I would be able to domesticate the vicious pain. But I was going to have to learn to train it if I was ever going to function in my new reality.

The year following Reed’s death was a blur. I was already home in California, taking my sophomore year of college off and living with my parents for mental and physical health reasons, when we got the news on August 20, 2015. I was nineteen years old, Reed was only twenty-one. For the first few weeks, family members and friends and acquaintances and people I hadn’t heard from in seven years were at my house day in and day out. I started drinking and smoking weed again. I picked out his urn online. I saw and held his physical body for the last time. I took care of my distraught parents. I didn’t cry at the memorial. I slept and ate too much. I watched a lot of mindless movies.

Like Hiccup, I did not try to reconcile with and understand my own dragon—the death of my brother—right away. I wanted to kill it, to undo it, to make it go away. I resented the fact I was now an only child, that this trauma would haunt me like a dark cloud for the rest of my life, that I would be the girl with the dead brother. But, unlike Hiccup, my dragon wasn’t a physical beast that could be killed. Where the young Viking chose to study and bond with Toothless instead of eradicating him, my choices were denial, despondence, or reconciliation. Knowing it would be an arduous and lifelong process, just as the training of Toothless is throughout the How to Train Your Dragon franchise, I still figured that my only chance at future contentment rested in learning to respect and embrace my grief. So, I trained my dragon.

Before his death, Reed and I had a persistently contentious relationship. We bonded as young kids, but my eager, perfectionist mindset and his charismatic, careless nature started clashing in early elementary school. I was the teacher’s pet and he was the class clown, and, by the time high school rolled around, Reed resented the freedoms I had as the youngest child who had earned the trust of our parents. I felt that Reed was irresponsible and unfairly critical of me, and I begrudged the fact that his charm and wit allowed him to avoid so many consequences. At the time he died, we hadn’t really spoken or seen each other in two months. I was surrounded by family and friends repeatedly fawning over his faultlessness while I was stuck processing the complicated, sometimes loving, very touchy sibling I’d known for 19 years. I didn’t know how to grieve him without pretending he was perfect like everyone around me was doing. With what felt like nowhere else to go, I asked for professional help.

I have been in consistent therapy for over three years now and, though my grief is not yet fully trained, I have learned to embrace it. My dragon will always be with me, and I hope to continually evolve with it. However, my experience since my brother’s death has illuminated a larger, more exhausting beast. You see, the bond created between Hiccup and Toothless in How to Train Your Dragon occurs at the end of the first act, just thirty minutes in. The remainder of the movie concerns Hiccup’s struggle to get the people of Berk, including his father, the chief Stoic the Vast (Gerard Butler), to appreciate and work with the misunderstood dragons instead of killing them. He is mocked and ostracized for being nonviolent, and, until the conclusion of the film, the people of Berk constantly show discomfort toward the idea that humans and dragons can coexist. I’ve found that, while training my grief has been hard, it is even more challenging to exist in a society that is so uncomfortable addressing or exploring the universal topic.

Our world is terrified of death and, at twenty-two years old, I’ve found it surprisingly difficult and exhausting to feel like I need to hide my trained dragon from people my age. How does one answer “Have any siblings?” on a first date without making the conversation irrevocably awkward? How do I explain to new friends why I started crying when Major Lazer’s “Be Together” played in the bar? It’s not easy, but if How to Train Your Dragon provides any solution, it rests in the last five minutes of the film. Having conquered the “mother dragon” controlling the smaller looting dragons with the help of Toothless, Stoic and the rest of Berk decide to embrace Hiccup’s message and begin training and bonding with their own dragons. Order is restored, and the revolutionized village is reinvigorated as countless citizens play and fly and work with dragons all around the colorful, lush island. Because they accepted the things that they were initially so eager to eradicate but couldn’t escape, they are left wiser, happier, and more content. I believe the same would happen if our culture took note and began embracing the topic of death and grief. I have personally found great solace in the training of my dragon.

Children’s movies, comfort films, and shallow media are made to make us feel safe and good, but that doesn’t mean they’re without substance. My reading of How to Train Your Dragon is symbolic and intentionally loose because this film—and many other kid’s movies like Wall-E (2008), Coraline (2009), Spirited Away (2001), and Inside Out (2015)—frames itself as fun entertainment while giving both children and adults the opportunity to apply the themes to their everyday issues. My dragon may be grieving my brother, but the metaphor can be used broadly. Any other viewer of How to Train Your Dragon might relate Toothless to personal struggles with insecurity, fear, abuse, or anything else applicable to their lives. It leaves the door open for interpretation, ultimately and generally saying that exploring the unknown, instead of fearing and repelling it, is rewarding. It is a message that is relevant now and always, and one that is perfectly presented through vivid animation, stunning music, and a richly painted relationship between a boy and his dragon.

It’s funny that Reed was the one who reintroduced me to a genre he had initially deterred me from outwardly loving. My family might disagree, but I know he would hate this piece and find it to be cloying and too sentimental. But what I’ve learned through training my dragon is that embracing grief will never change the relationship I once had with my brother. It feels apt that, even after all of this time and work spent evaluating my relationship with Reed and his death, our relationship is still contentious. Some things never change.