“Why does it feel so false to try to cultivate a unified representation of your person?”

Your Personal Brand

Why does it feel so false to try to cultivate a unified representation of your person? There is something fraudulent in the act of trying to look whole, as if we expect people to be born with a branded aesthetic. But I’m not talking about social media. What is concerning is that there seems be a connection between an undeveloped sense of self and a stuttering sense of self-image. Take my nine-year-old sister. The way she speaks, the things she values, what she thinks is pretty are all mined from what she considers to be legitimate sources: radio ads, her skinnier, richer friends, and so on. Her naive and obvious attempts at developing into a person provoke a weirdly intense feeling of disgust within me. I want to shake her, tell her to be a genuine child, “Just be yourself!” But how unfair of me! At nine there is no genuine thing she can be other than a girl in transition. At twenty, I’m wondering if this state of confusion really ever ends.

Underlying all of this is the assumption that a genuine self and all the symbols and sense of style that accompany a fully developed personality must have been something you were born with. If the seeds of eloquence, strength, decisiveness, cohesive lifestyle, and a keen instinct towards the way you can best beautify and manage your body haven’t pushed through the hard spring earth of puberty, then unfortunately you’ve been dealt the card of not having a personality. Joan Didion’s sketch of those lacking self-respect comes close to the fear I’m trying to characterize: “You run away to find yourself and you find that there’s no one home.”

At fifteen I thought most, if not all, life paths were closed to me. If I could not look back to my childhood and see the prophecy of my future career as a painter, let’s say, shining in a series of portraits I had made at age five, or some unnoticed (but now blooming) quirk, such as being particularly fascinated with the colors of things, then it was never meant to be. I could be a painter, sure, but probably not a very famous one.

I blame geniuses, child prodigies. I blame the people who kept talking to me about their cousin in France who’s a literary critic at age twelve or someone’s three-year-old that is already better at playing the piano than I will ever be, and no, I haven’t ever tried, but still, why bother, with this three-year-old around? The problem is that, like it or not, “born-that-way” does exist, and all of us dreaming to escape the bounds of ever-horrifying mediocrity see these examples and shrivel like grapes in the sun.

Once we realize that we haven’t seen any prophecies, the whole project of actively constructing yourself and your future goes absolutely limp. “Working hard at it” is for those who deserve it, who are going there by dint of their talents and the necessary travail that follows. For the rest of us, of course, we are only sad actors in parts we never intended to play, or we are those 40-year-old people that have proclaimed “it’s never too late!” though we know that by now it is. And in the midst of all of this, you don’t own any pants that fit right.

There is an undeniable link between this evasive sense of self and sense of style. But, if we have long ago foreclosed the possibility of ever being “somebody” then how, exactly, are we supposed to get dressed in the morning? Any attempt becomes the near-traumatic experience of feeling stupid in your dressing room, or hastily wiping off the lipstick that you should’ve known would highlight the smallness of your mouth. To try to construct your image is to invite the shame of playing at beautiful, to invite the pathetic suspicion that you’re playing dress up in someone else’s clothing. Playing at someone else’s personality.

In the midst of all this self-pity, and wishing, is the complaint that even if one was to pursue the active effort of making oneself, there is really nowhere to turn in this hell of the modern condition. If we are to take the cliché that modernity is ruled by isolation, lack of real community and culture, where is one supposed to mine adornments for the body that actually mean something, that are not just the fast fashion equivalents of finer clothing?

As a child I could not help but prescribe incredible meaning to anything old. New clothes from Gap, new utensils from Ikea, new sheets from Kmart — none of these things meant much because not only did they lack a history, they lacked the potential for history. Who is going to make a family heirloom of your Aerie sweater? But old things were precious by virtue of being old. They had lived a life with someone else, and had proven their worth by being good enough to pass down. A natural selection of objects. Later on in my life, a personal study of folk art and fashion would re-open this door of fascination, for here was the logic of old things: meaning is made in social circulation, in the giving and taking.

I’ve come to define folk craft as the merging of self, community, and environment. Yanagi Soetsu, a philosopher of folk arts, wrote extensively about this subject in his book “The Unknown Craftsman.” His chapter on patterns give us a good sense of how these three subjects merge and transmute themselves into art.

To paraphrase, the pattern is the viewpoint that regards nature as beautiful, sums it up, and transforms it into a general shape. The pattern is then communally held because the relationship between a people and a symbol is known. In this way, individuals within a community come to share and invest in something that transcends the individual, while also retaining the ability to use it in daily life by adapting the pattern to the materials available and the functions needed. In this last point lies the crux of things: the freedom to interact personally with something that holds meaning for you and your loved ones.

Given this example, one finds it difficult to imagine that shared symbols, which we are able to manifest in our lives (when making our clothing, when building one’s home), can exist in the age of the individual. In an age where we are all so starved that the invention of a pattern must be guarded and patented just so one can make a living, there is no room to share, nor is there room to be the craftsperson of your life.

This may be a tired critique, but who among us isn’t disassociated completely from the materials and symbols with which we choose to clothe ourselves? Now ruled by mobility, who is attached to place and pattern? But let me try this pattern-making : in the city I might choose, by proximity, the image of windows and trash, those ever-proliferating patterns which border me as I walk down the street. But it is a lonely and unattached thing to create a pattern alone. Where is the meaning made by sharing a history?

Then again, I am speaking as a first-generation American who grew up in the Hamptons. I may be a case study for an individual without concrete community and culture — I know that there are many in the States alone who have a communal life to draw pattern from. Early on in my life I decided that to be Hispanic was to be poor, thus I severed any linkage with my heritage. Later on, I would become disillusioned and ashamed of my attempts to look like the rich white ladies who were mothers to many of my friends. They were well-educated, well-traveled, and capable of living in all white houses. What is sad, looking back, was the plain evidence on their faces and in their words that they were not sure they had enough.

I would find out too late that I had made my childhood wish come true. I talked like them, I wanted the same things as them, and my Spanish was in emaciated condition after years of refusing to speak back to my parents in our native tongue. I felt that I could not, now, decide to make a false bridge to a person I had made sure never to become.

So in my studies, in the books I love, I try to go back in time, all the time. But let me go back even further than Victorian England and Japanese folklore, because it is at the beginning of civilization that we may find solace for our modern condition of the unknown self and things not shared. Maybe at the beginning of humanity there is someone who can tell me what I can be because they will tell me what it means to be human.

Inanna was a goddess in Mesopotamian myth. She was queen of heaven, morning star, the exception to the men and women around her because she was neither. She was a warrior, a politician, a seductress, a wife, an earlier Prometheus, and the one who would venture to the underworld. On her wedding day she smeared honey on her thighs and wore golden genitalia as a headpiece. She stood on the mounds of lapis lazuli that her betrothed had brought her. The image is almost too bright—she was shy and excited. I read that her associations with different animal symbols were based on Neolithic continuities. These people saw the snake and the mother as one would create figurines whose names we would not know. Inanna would follow. In the perverse manner of history, Eve would become the evil heir to the symbol of fertility and continued life.

The works on Inanna are many, but most important to the present discussion is the epic tale of her journey to hell. When Inanna decided that she must go to the underworld, for reasons unknown to her and to us, she abandoned her temples, made contingency plans, and then she got dressed.

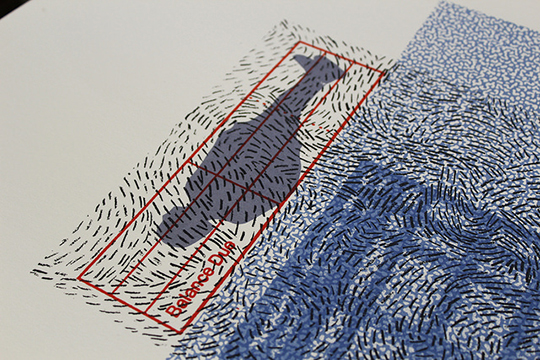

She wore eyeliner and a pectoral pendant both named “Come man, come.” She wore the pala dress of ladyship, and the measuring rod and line of the ruler. She wore the turban of the traveler and a wig to protect her forehead. She placed a string of lapis lazuli around her neck and arrived at the entrance of hell the size of a mountain.

The goddess of Death, Ereshkigal, told her attendant to let Inanna in, on the condition that at each gate, a piece or two of her attire be taken away. She agreed, but at each gate she could not help but ask, “Why?”

When Inanna arrived, finally, at the goddess of death, having crossed the seven gates, she was naked, barely lucid, but probably still wearing eyeliner. She was struck down for her presumption, who was she to dare cross into this territory alive, perhaps coveting the throne of death itself? So Inanna’s corpse was hung on a hook, like the skinned cow before the butcher.

Was this it, then? Was all structure false? Could it be that the symbols that represented who Inanna was in life, when stripped one by one, would reveal that they had been empty all along? Was Inanna nothing less, essentially, than what she died with—which was nothing?

Here is death, the great motivator. If you don’t know who you are, or what you want to be, or how you want to live your life, better find out soon before the chance to live has been spent fretting and not-being. There remains the fear, on top of this, that if you were not born with special powers—talent, intelligence, a family of means, a future of means, then we cannot get to this “full life,” the one you can look back on and say you’ve nothing left to do. This will never end, there is no solution to it, you are what you are.

I know a woman who lives a quiet life, and, nevertheless, she remains in my eye the star of class and poise. She’s getting older now, and I have gathered from her passing comments that she is dissatisfied with what she sees when she looks back on her 60 or 70 years. I find this hard to believe, and for some reason it is explicitly because there is not one item of clothing, upholstery, art and so on that decorates her home and body that has not been skillfully picked and maintained with care. The decisiveness of her style so completely convinces me of her worth — what magic to have taste and then manifest it. To take life into your hands with the strength and skill necessary to bring about such beautiful, lived, order.

If this could be enough, to not be Inanna, or Didion, but to know yourself, and manifest yourself in images, then there is only one thing left to do: make reality bizarre.

Viktor Shklovsky, the early twentieth-century literary theorist, conceptualized the idea of literary “estrangement.” He tells us that our lives are eaten up when all their parts seem automatic. We take for granted the shape of things, their smells, and so on. He argued that in literature, the writer must make the assumed seem strange to bring them back to life, so that we may appreciate them, and know them. Do this exercise: Walk through Washington Square Park, look at the trees and think to yourself, over and over again, how strange their forms are. That an alien would see the white spears of their trunks rising from the ground, living, producing our air, and think them a miracle worthy of devotion.

To be in awe is a beautiful way to live your life. There is also the bonus that, in loving things, you begin your own natural selection process. You look hard enough at the things around and the things within you, and assumptions of value are stripped away until all that remains are your own. Alone with the only thing you can hope to influence—your way of seeing.