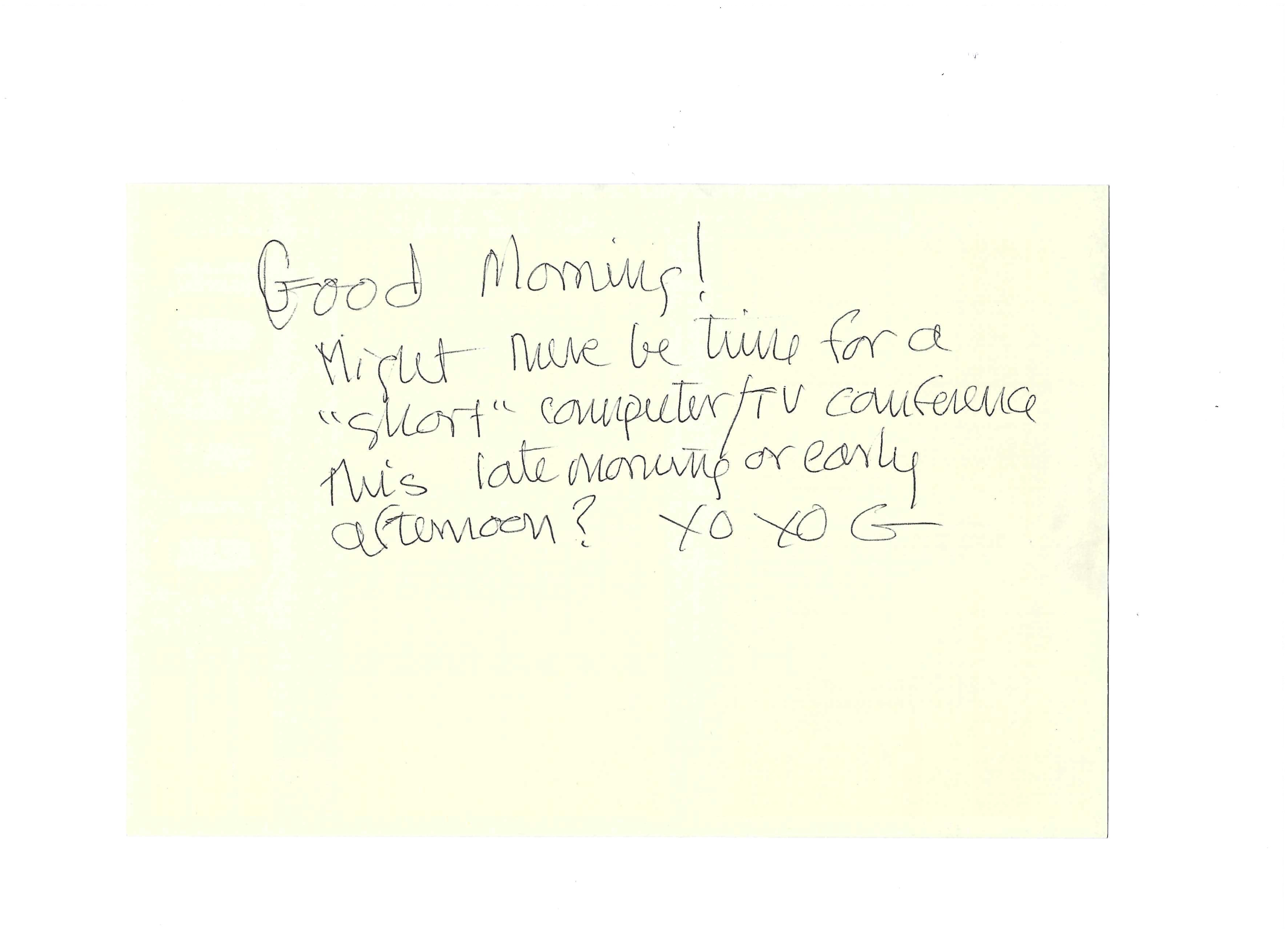

A slip of paper negotiates its way under my door.

If You Have Some Time Today…

1.

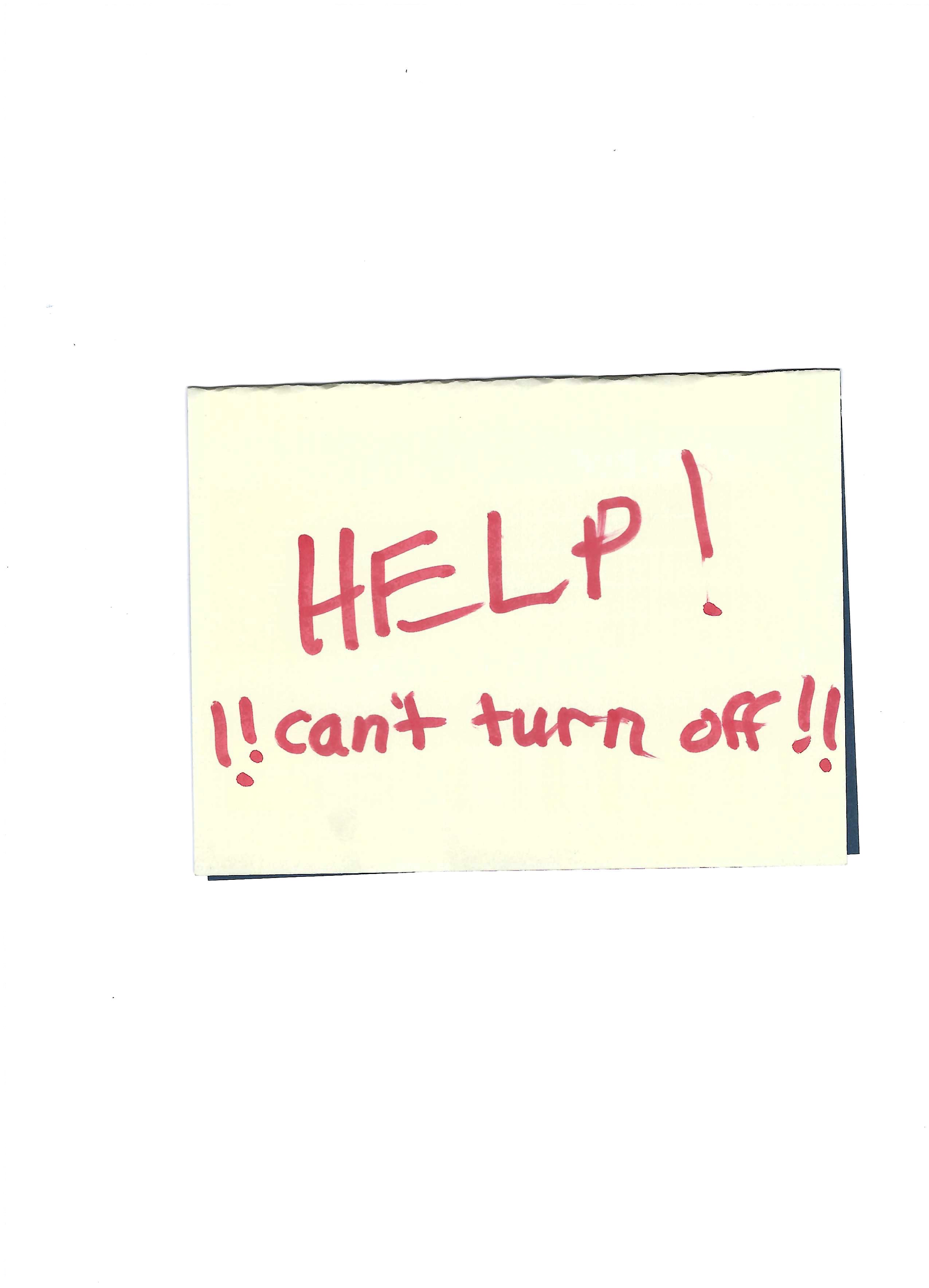

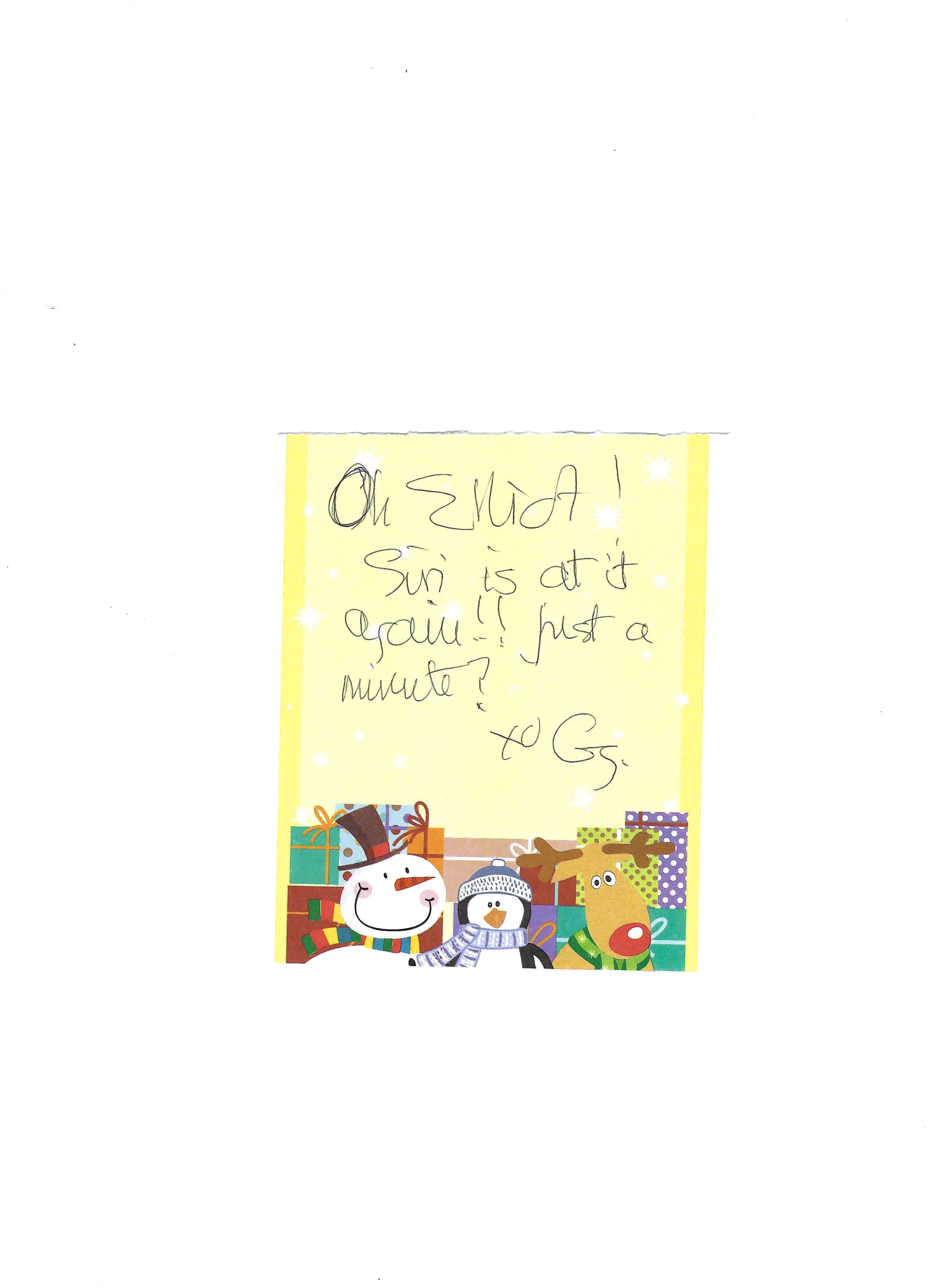

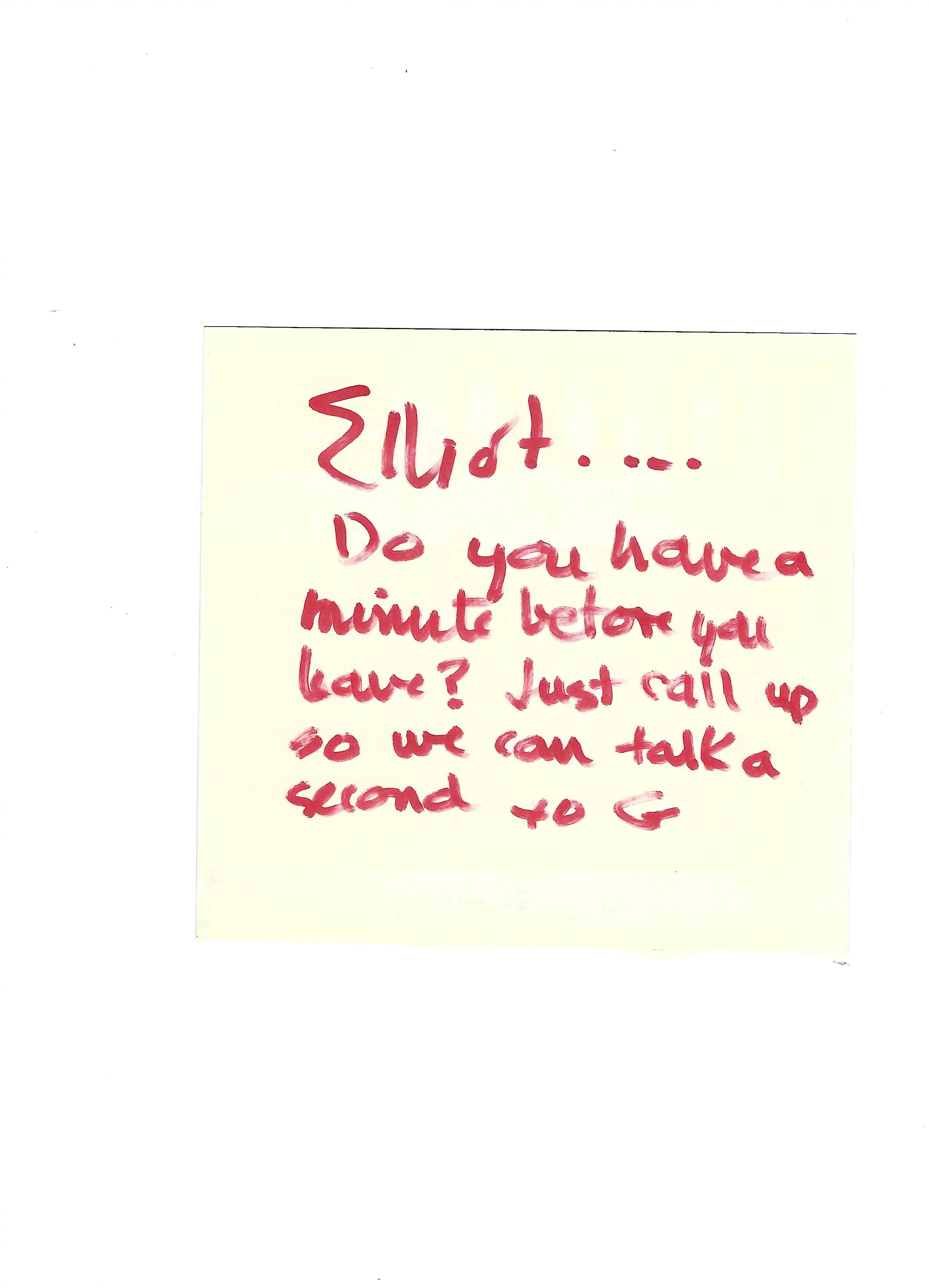

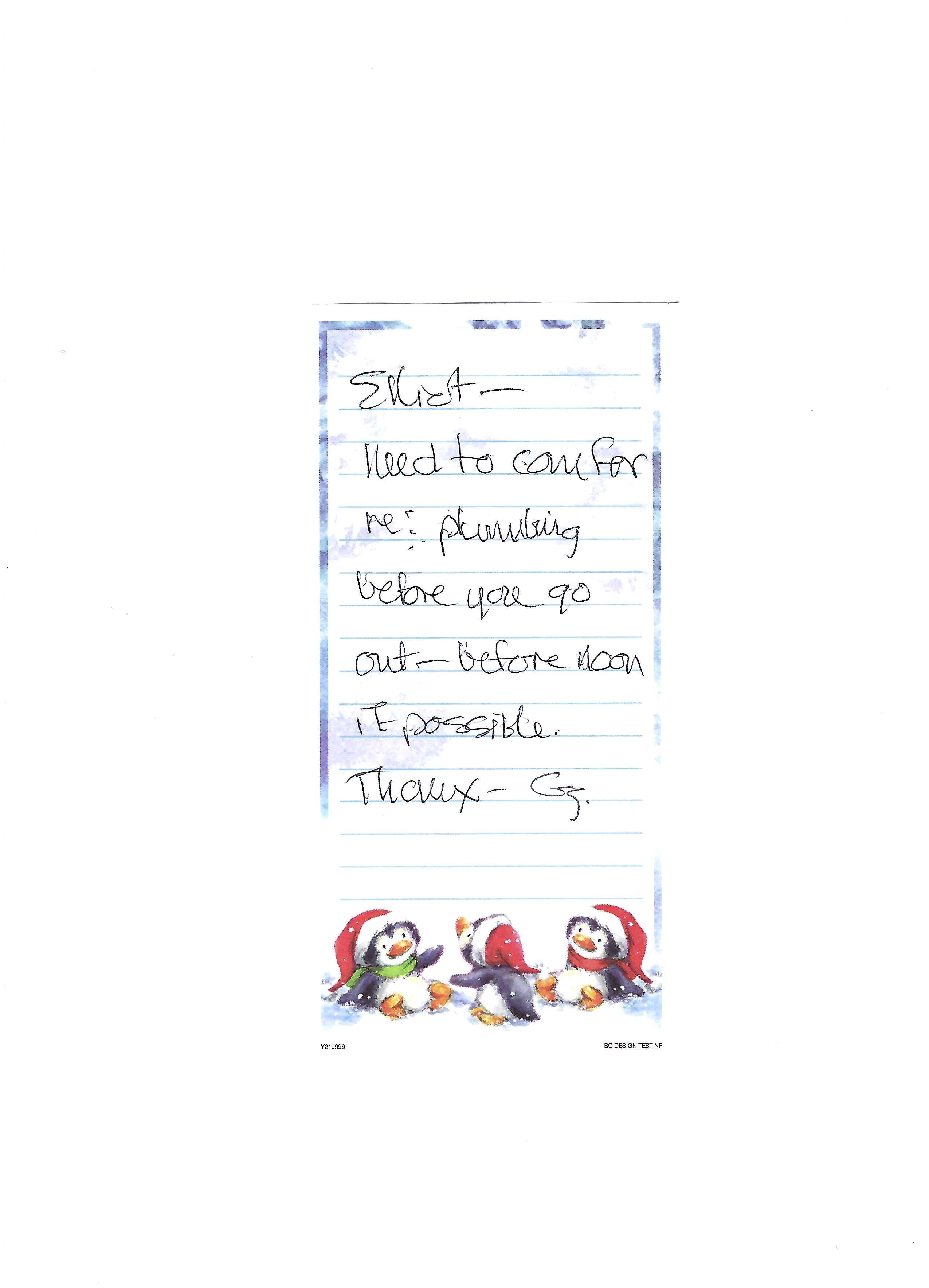

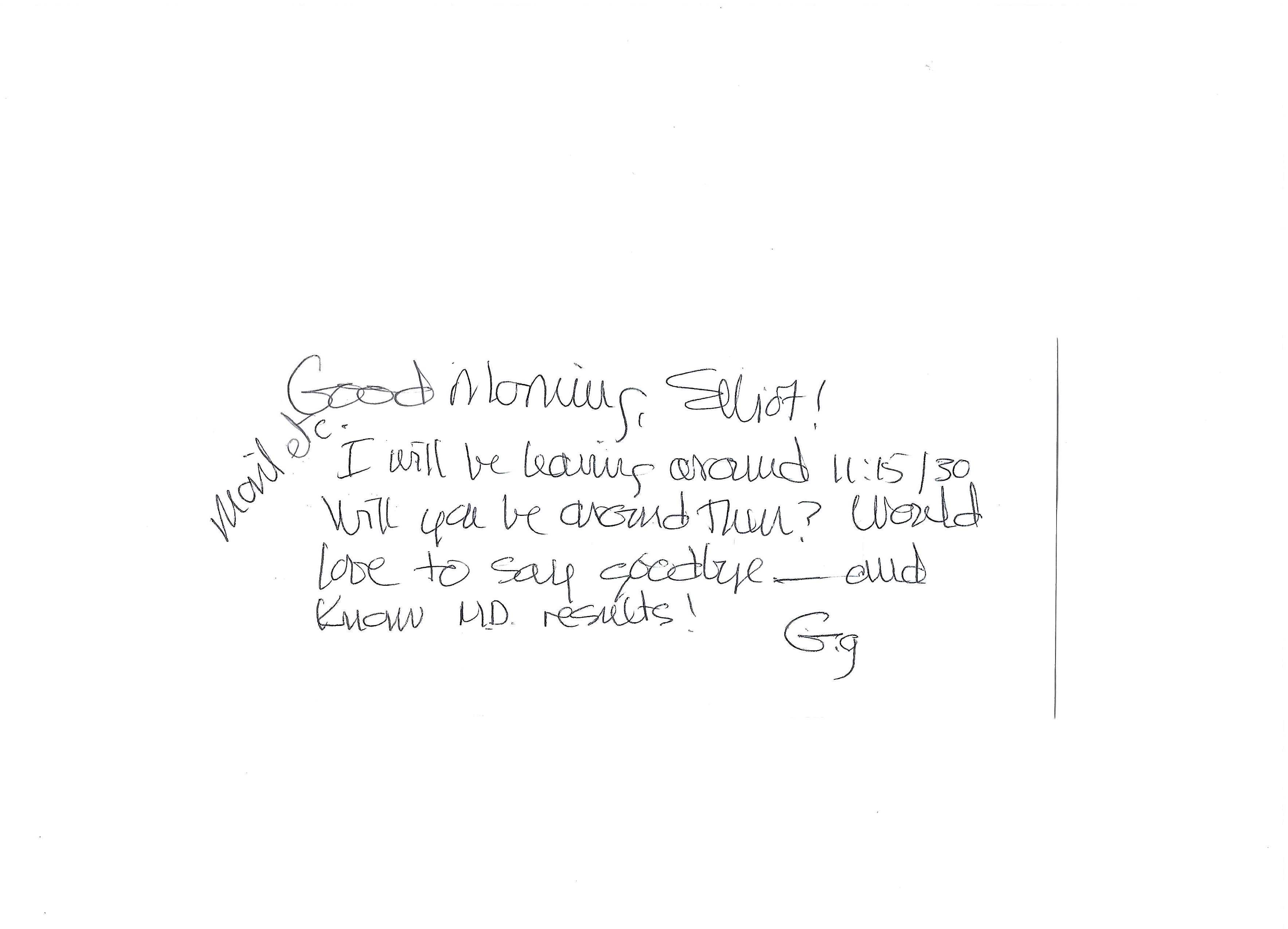

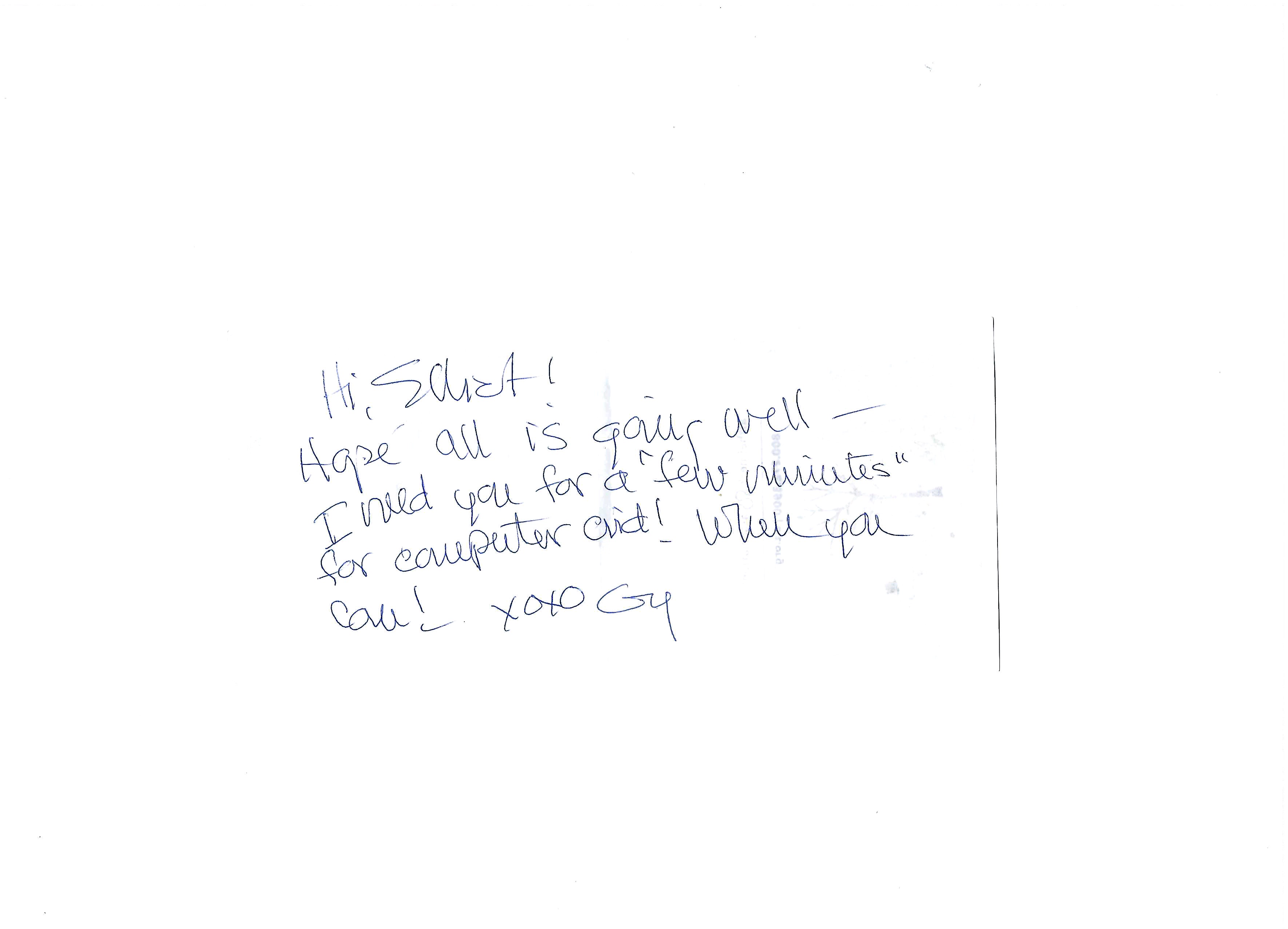

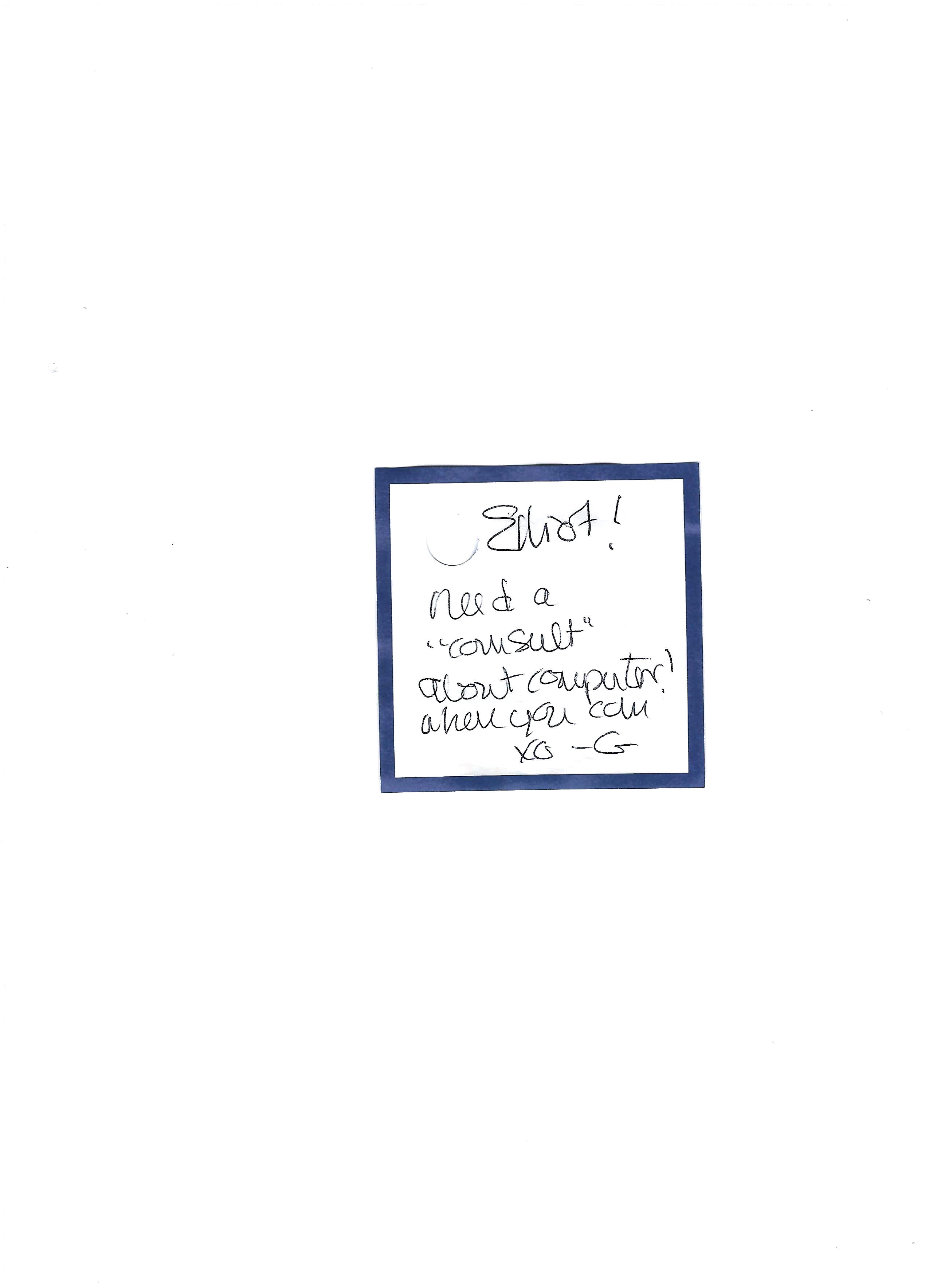

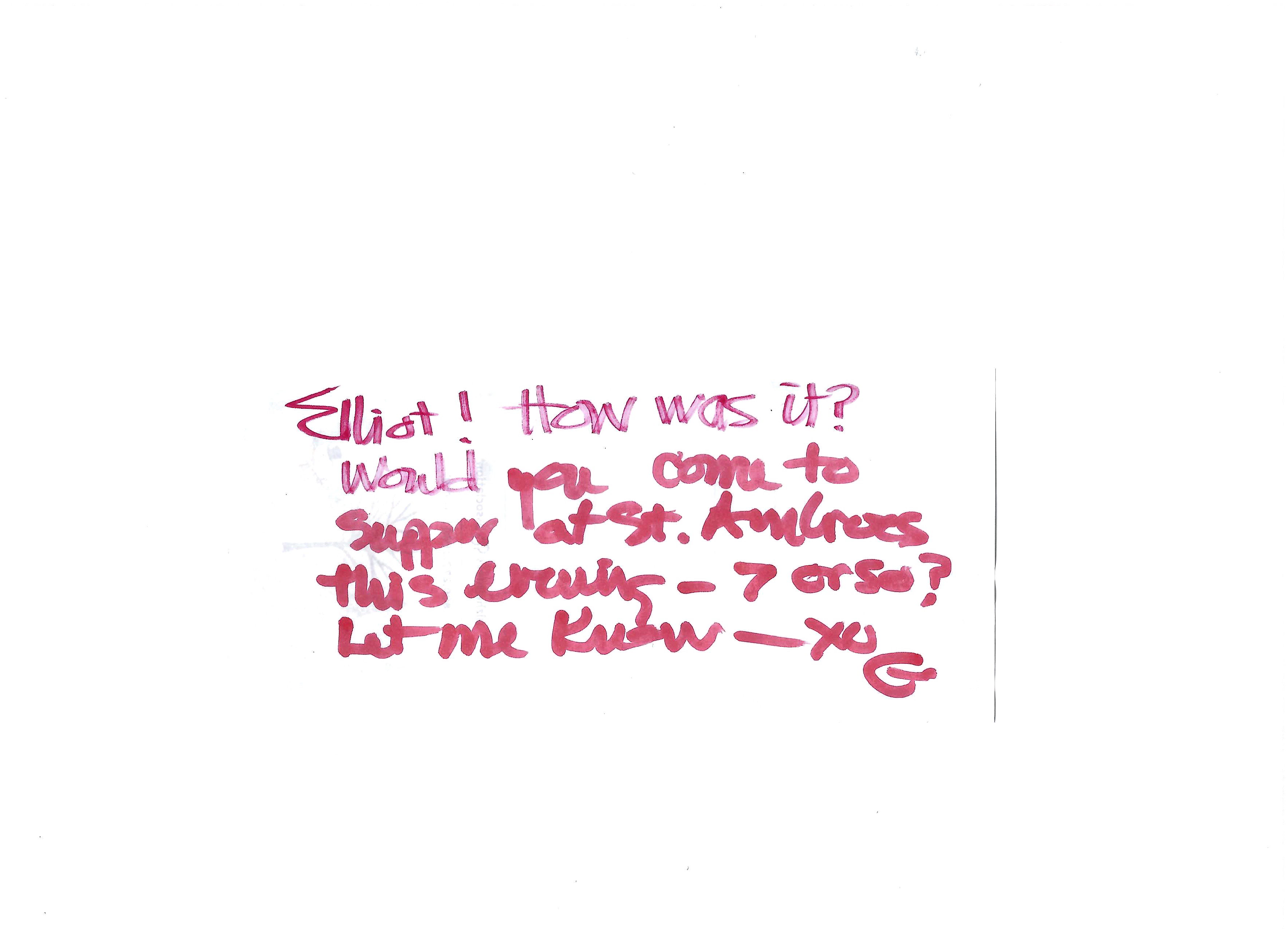

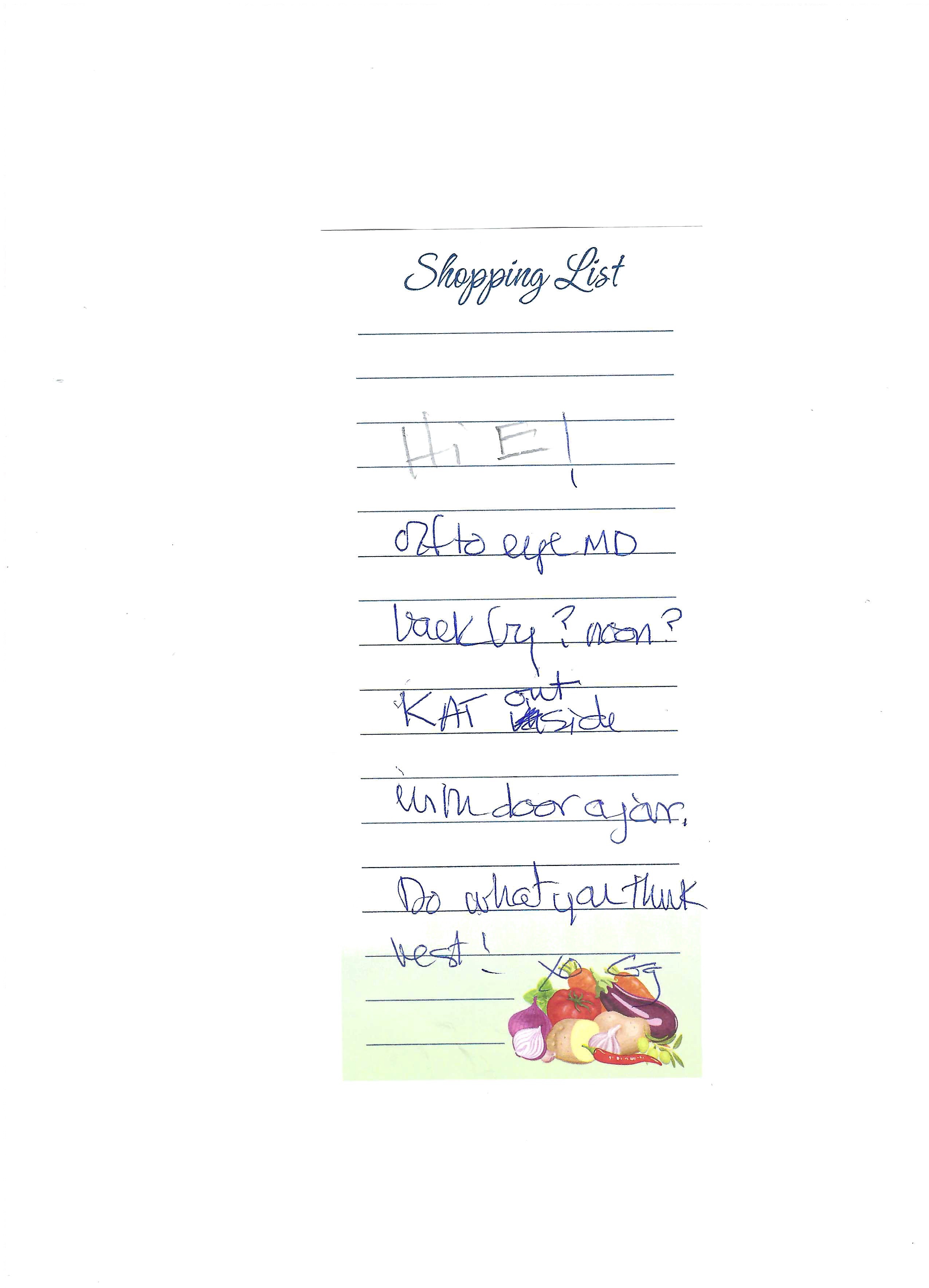

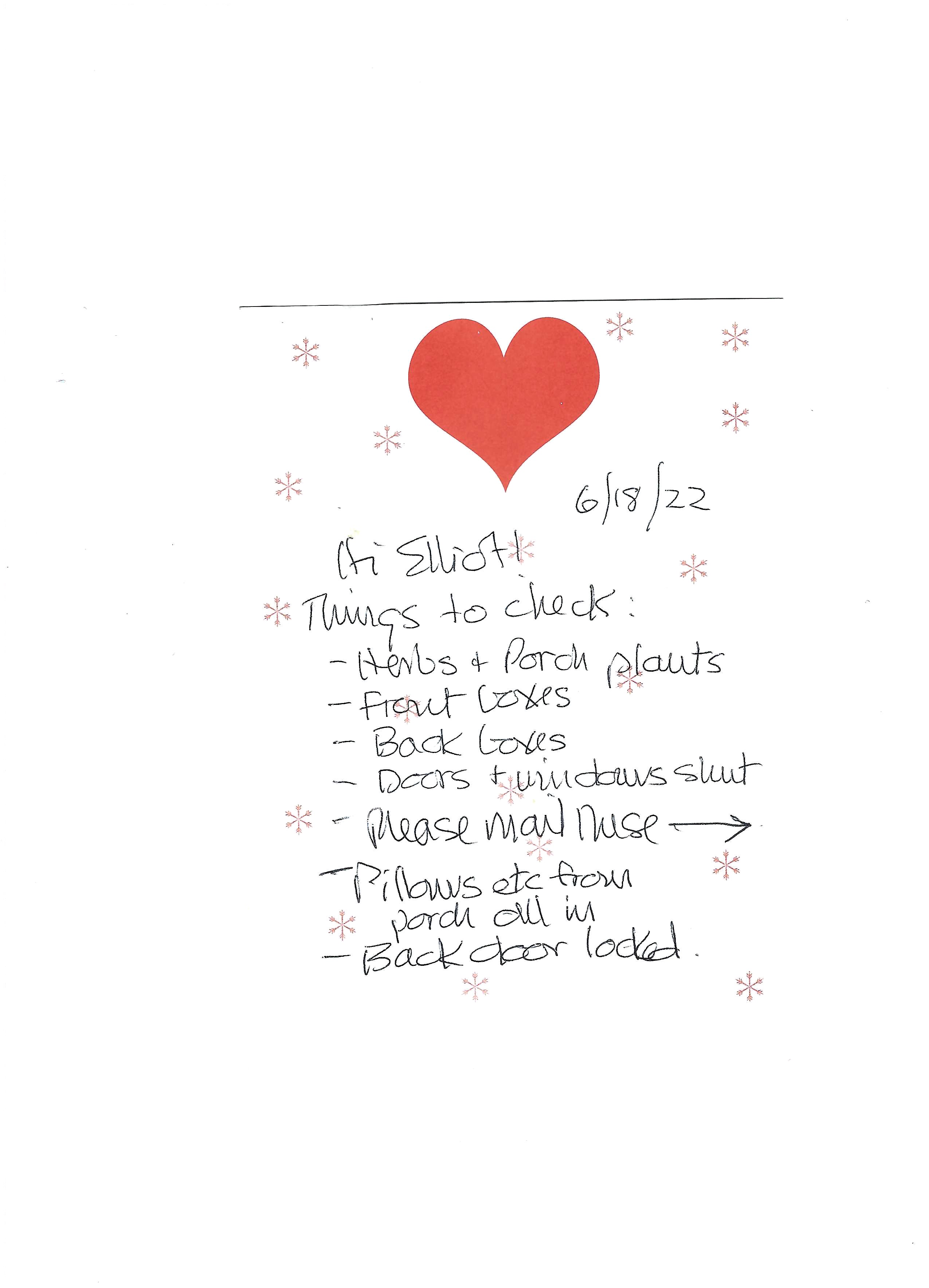

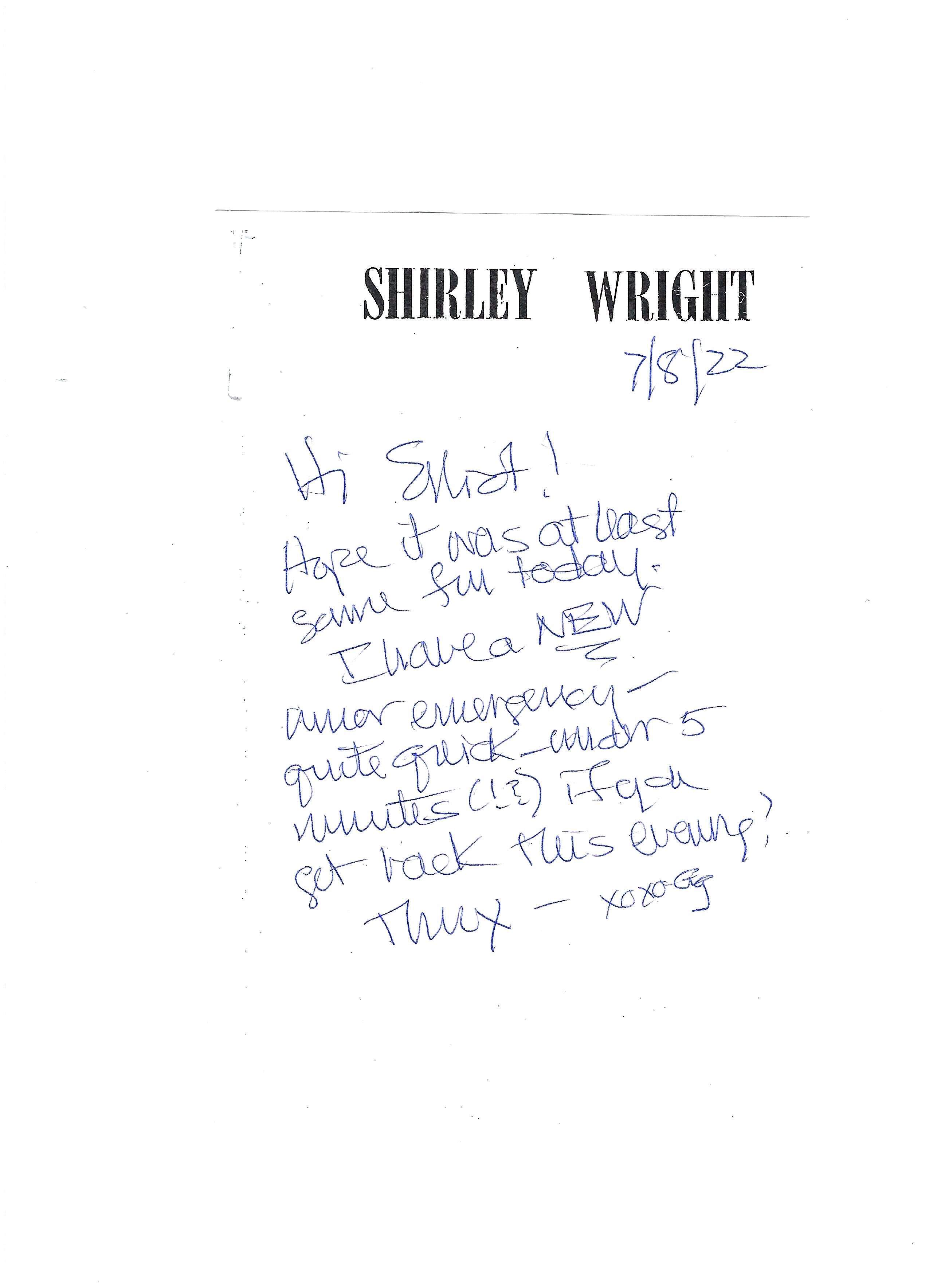

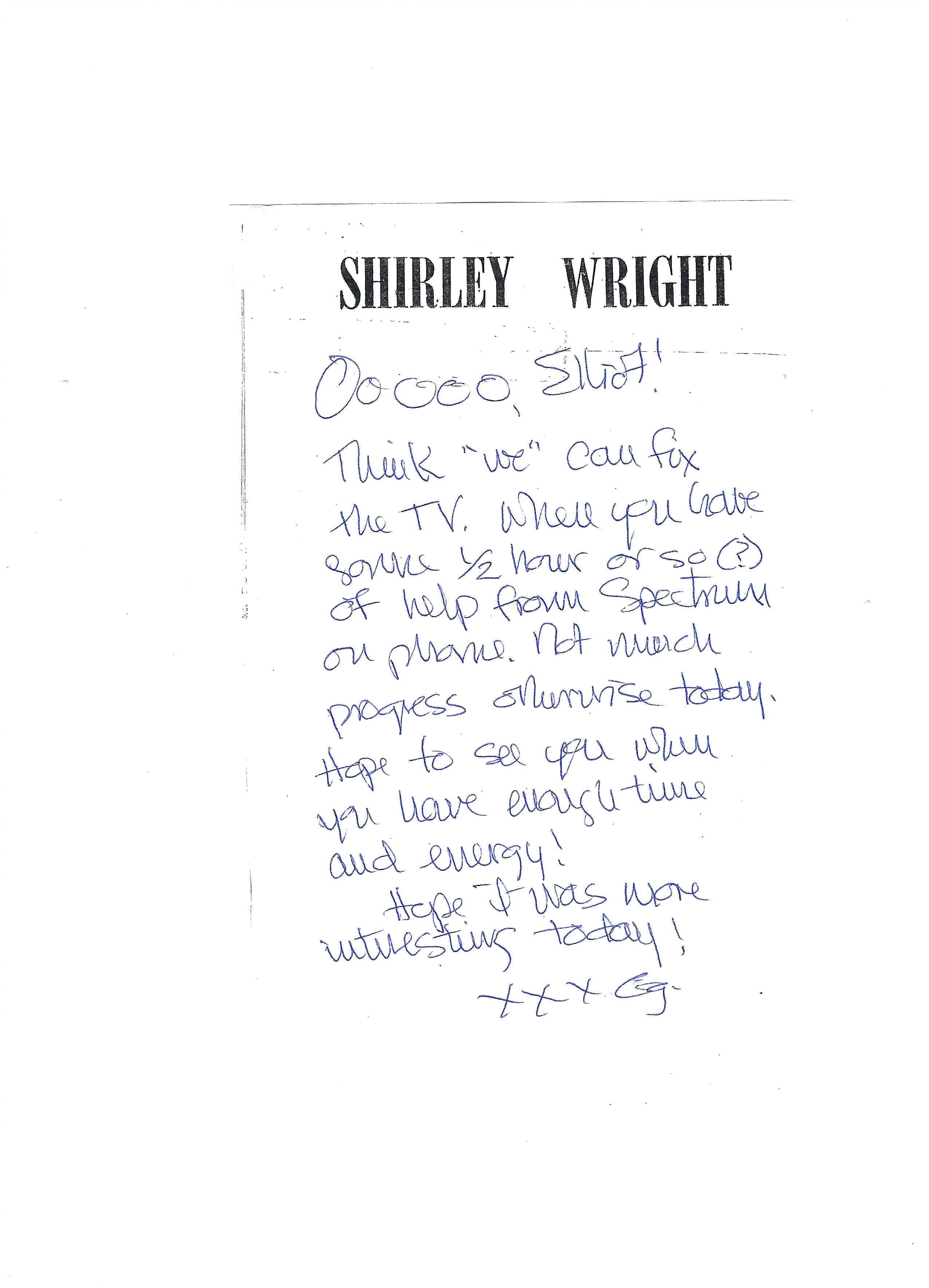

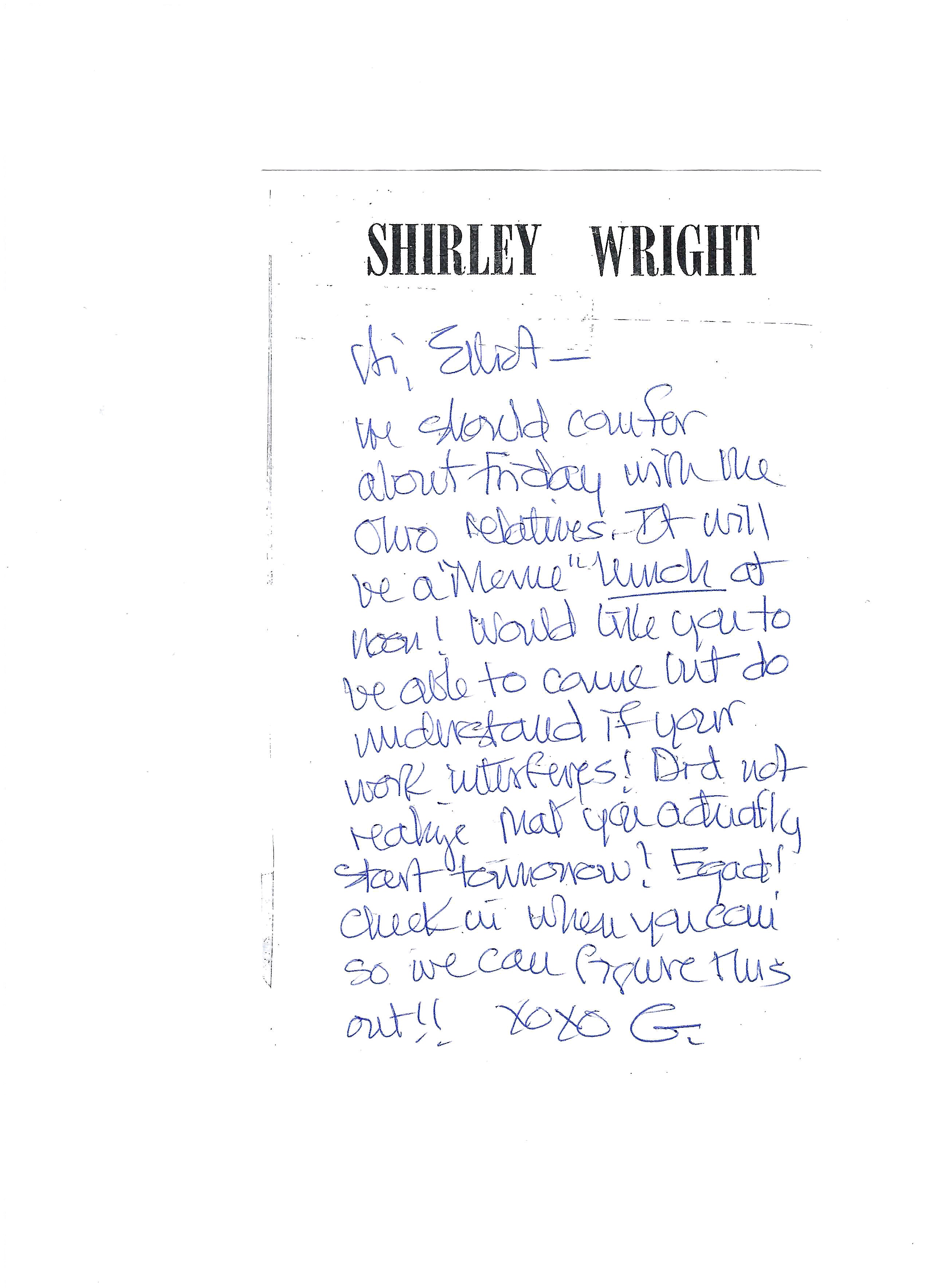

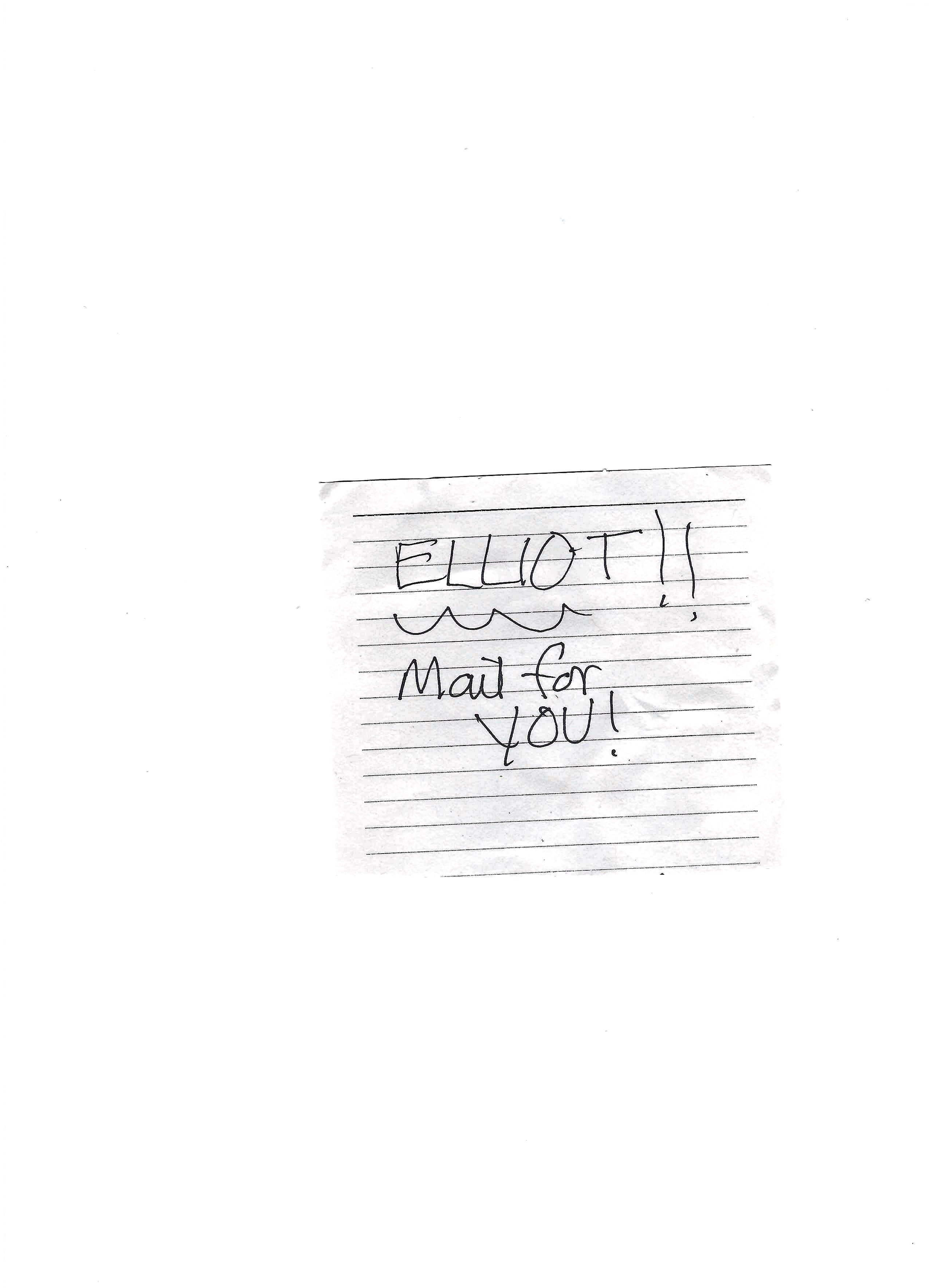

A slip of paper negotiates its way under my door. Written in red magic marker is the following message:

Elliot….

Do you have a minute before you leave? Just call up so we can talk a second

xo G

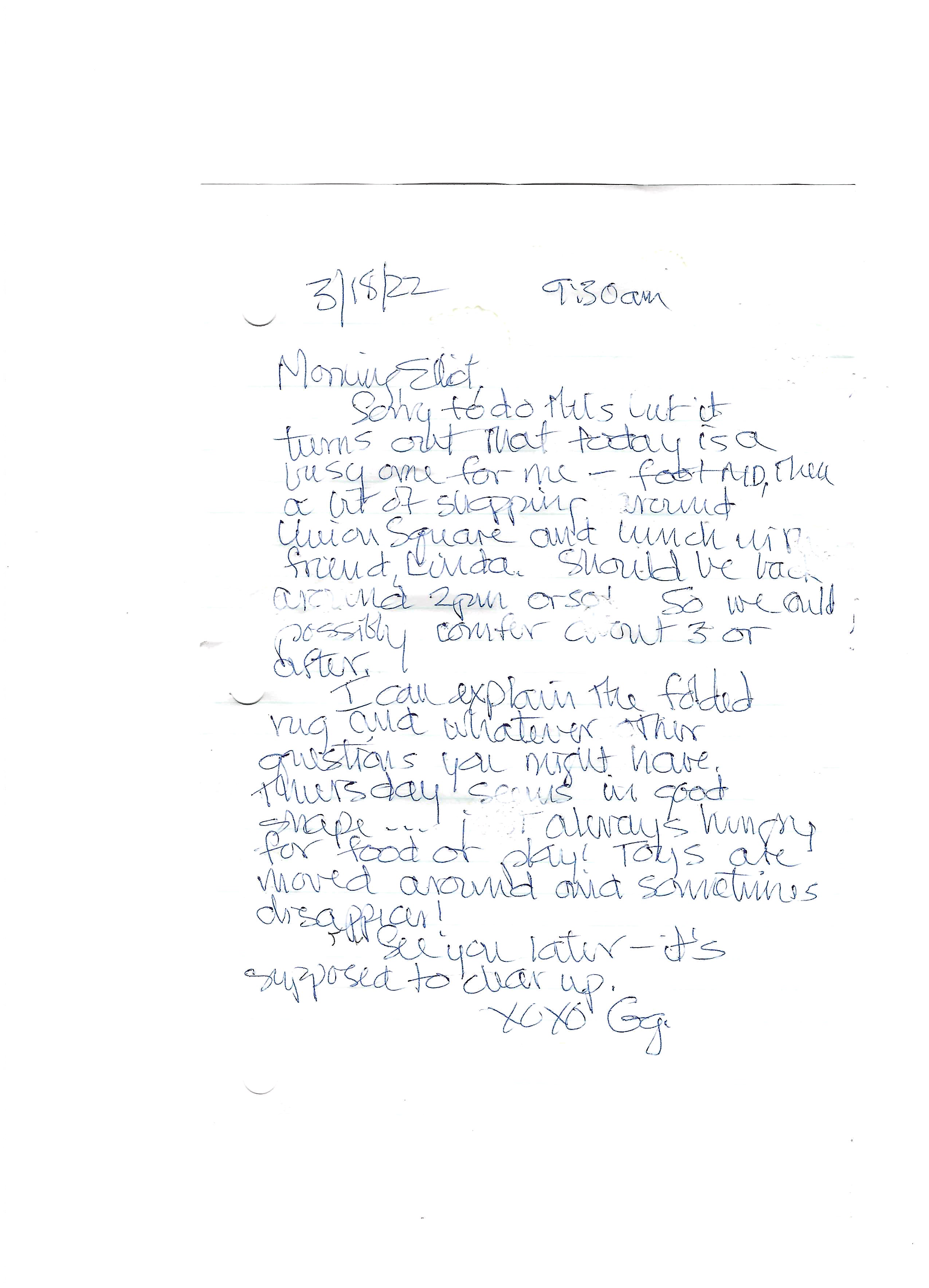

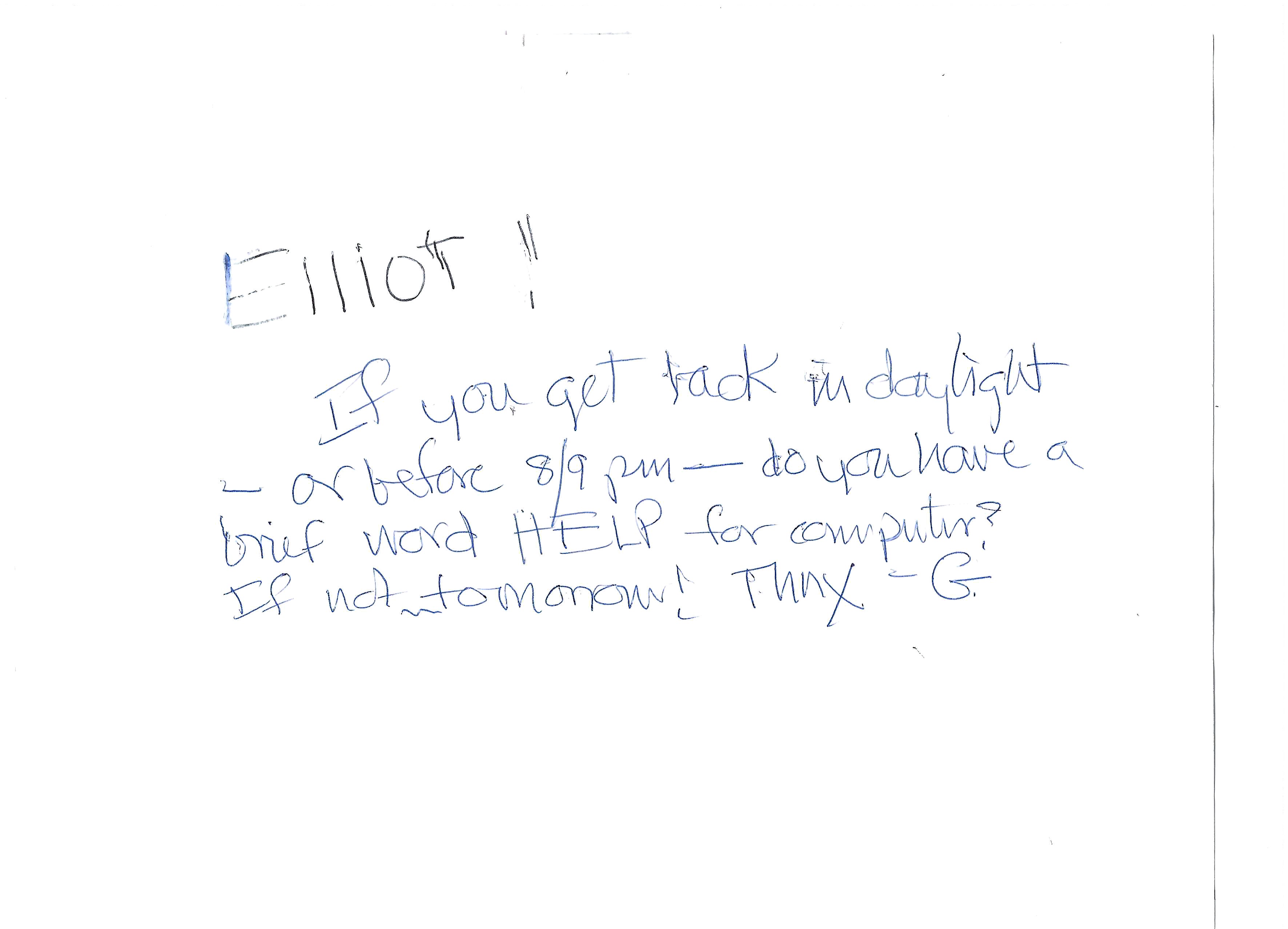

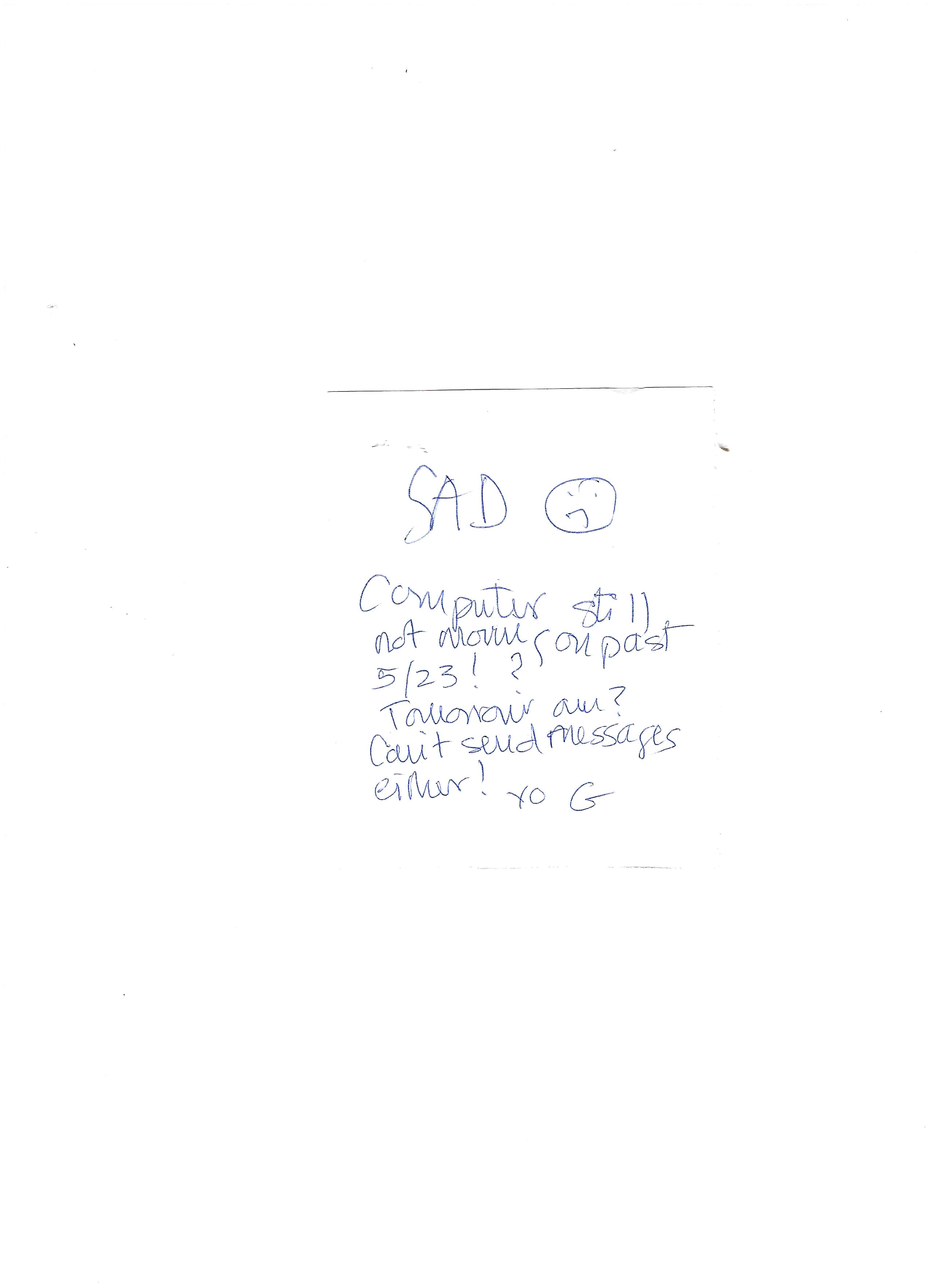

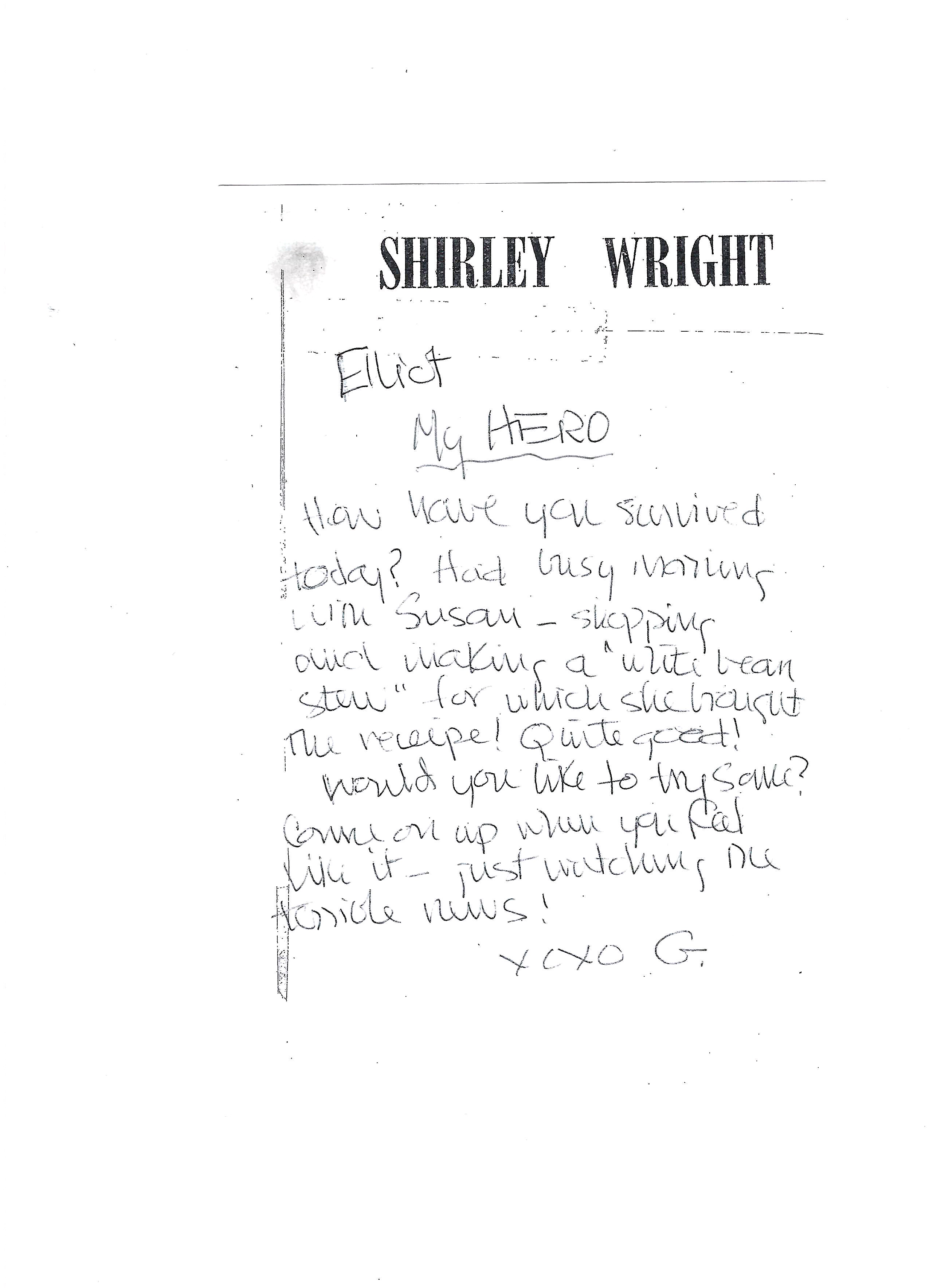

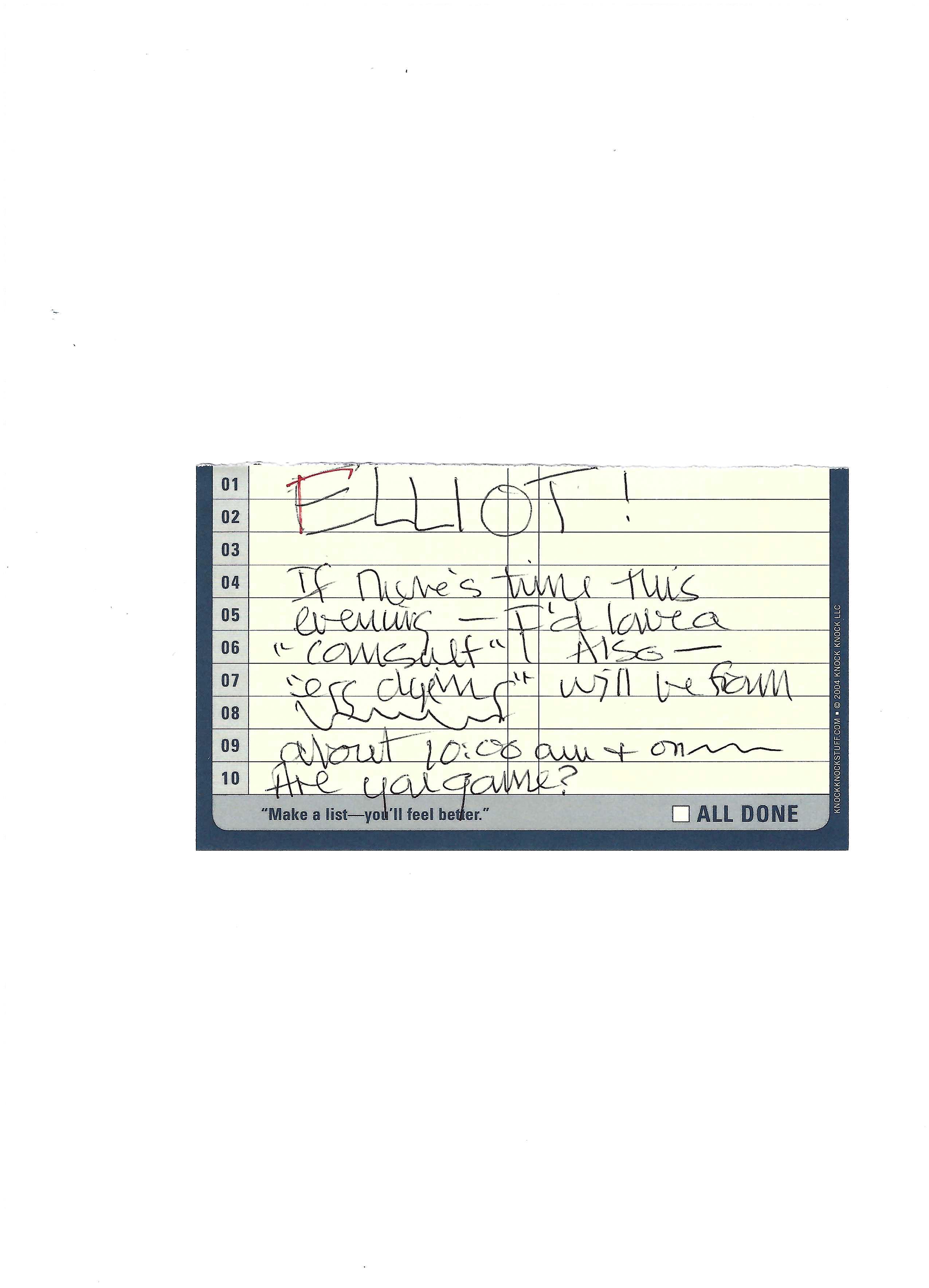

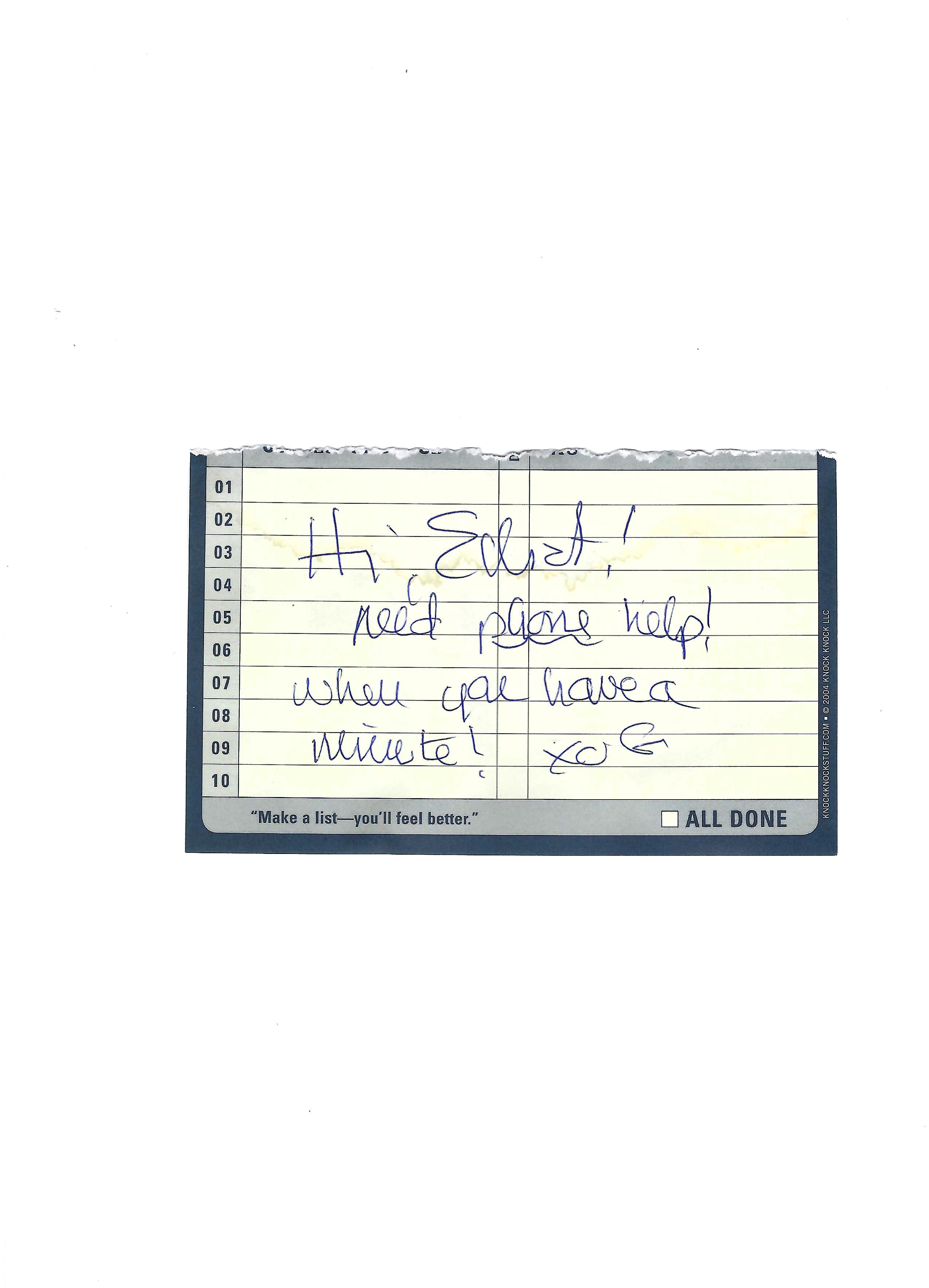

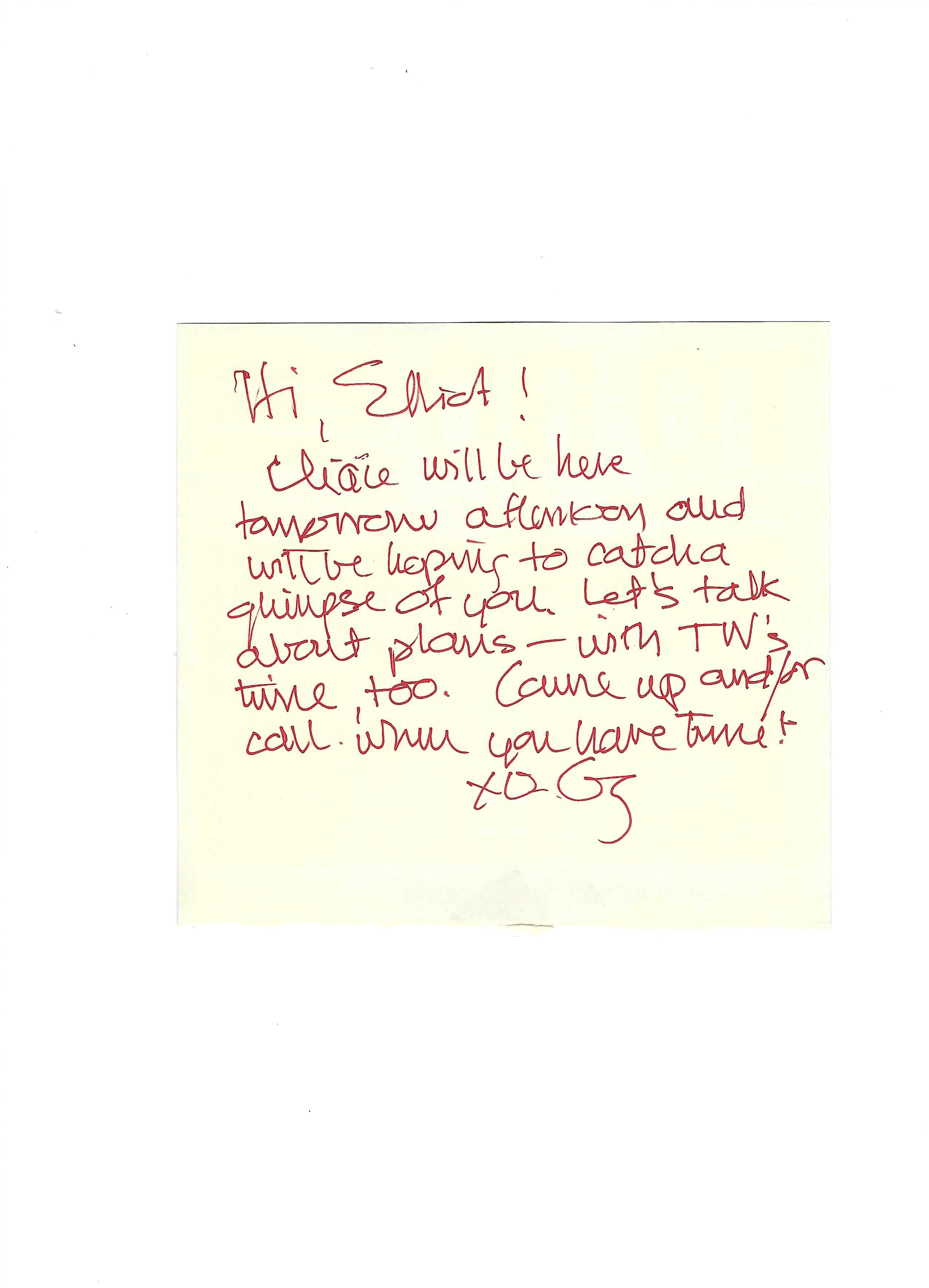

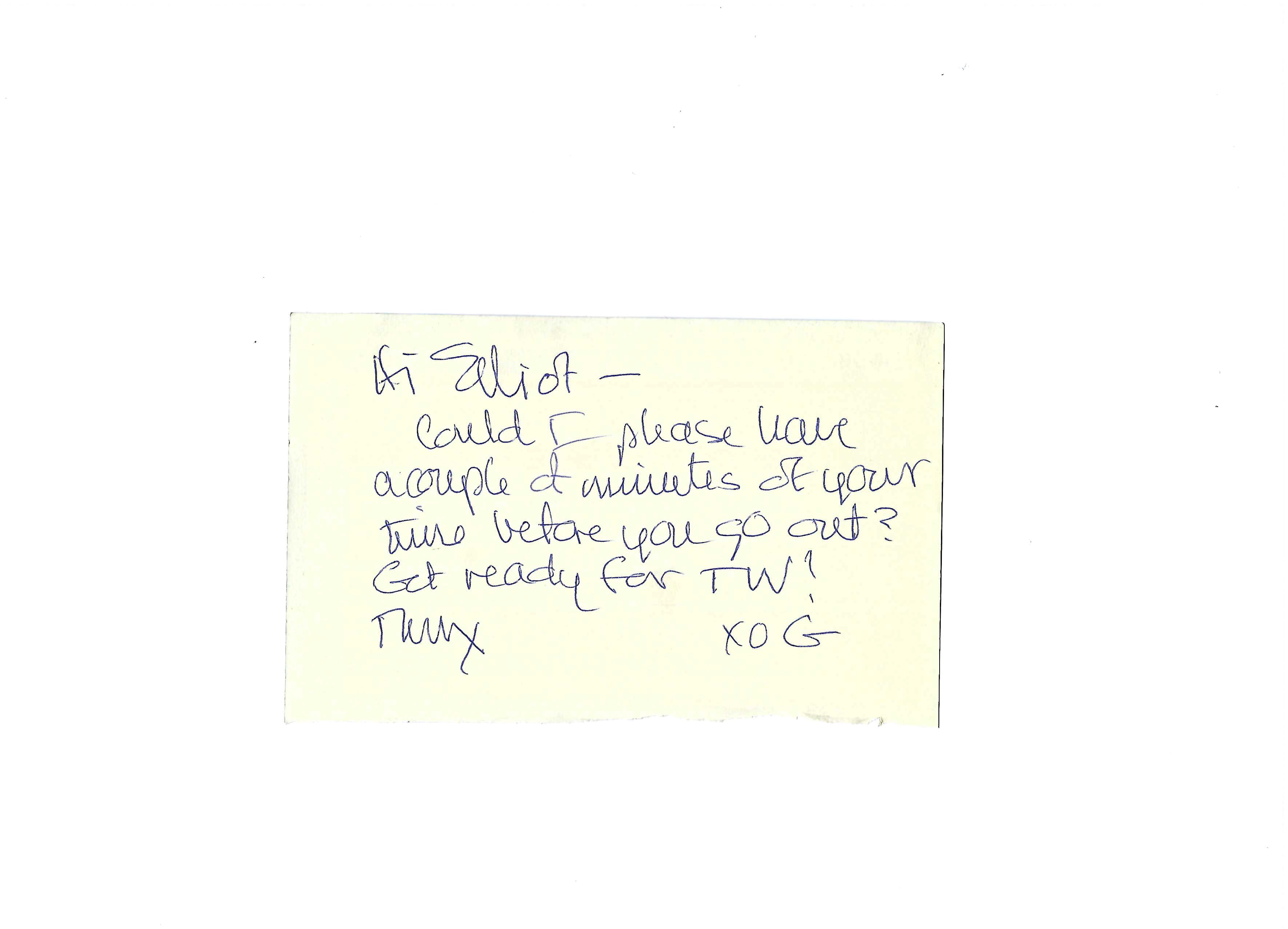

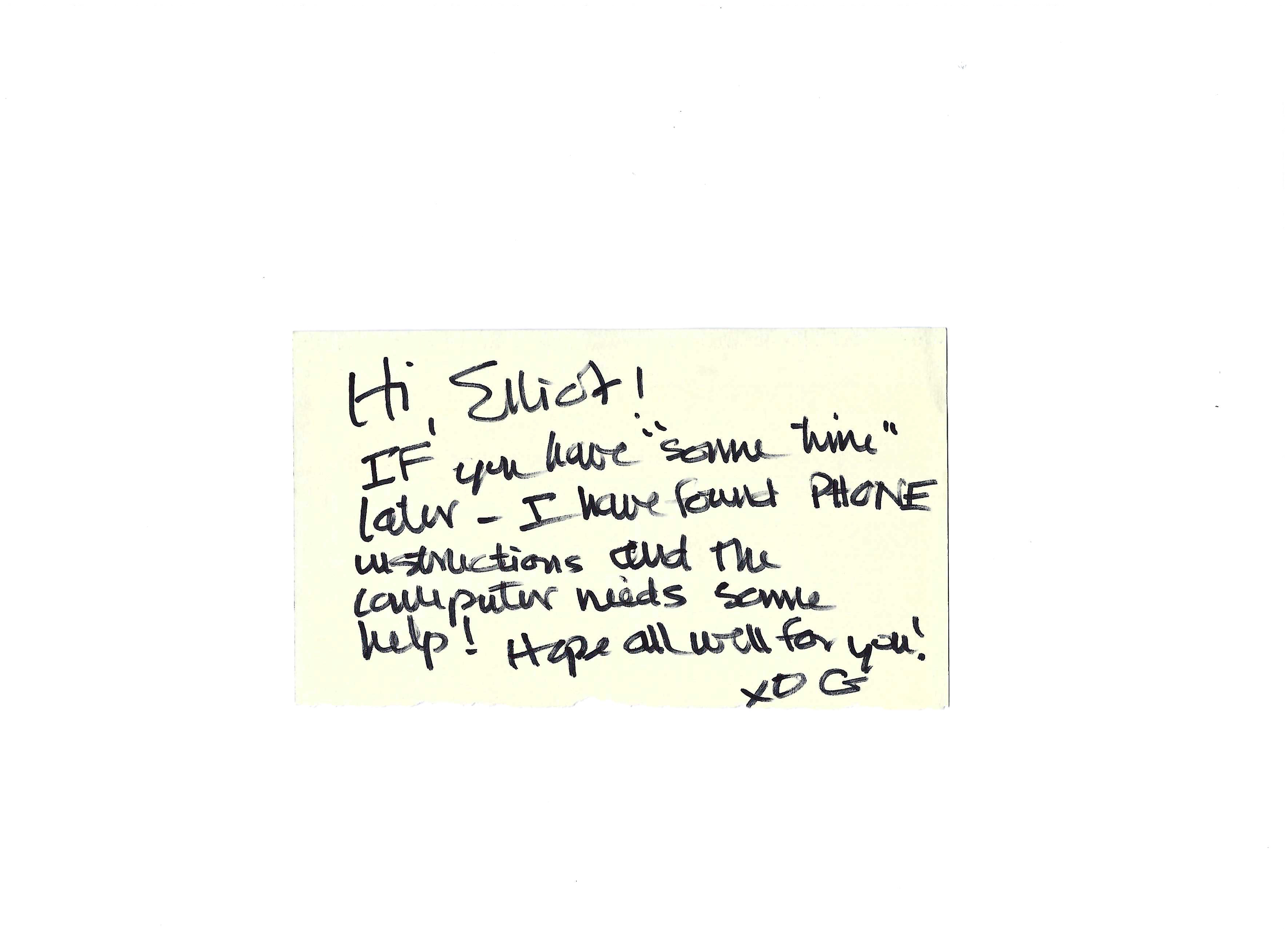

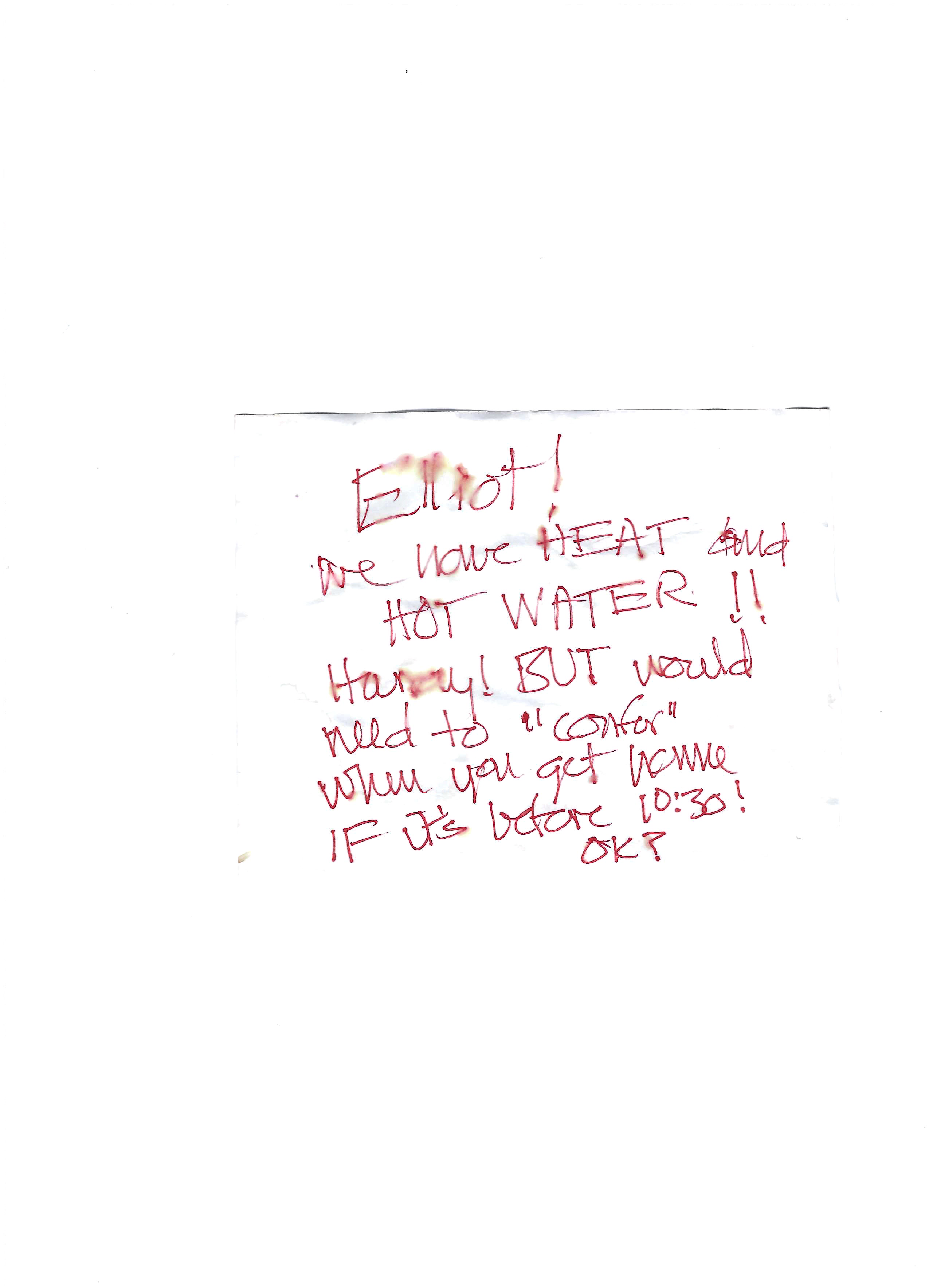

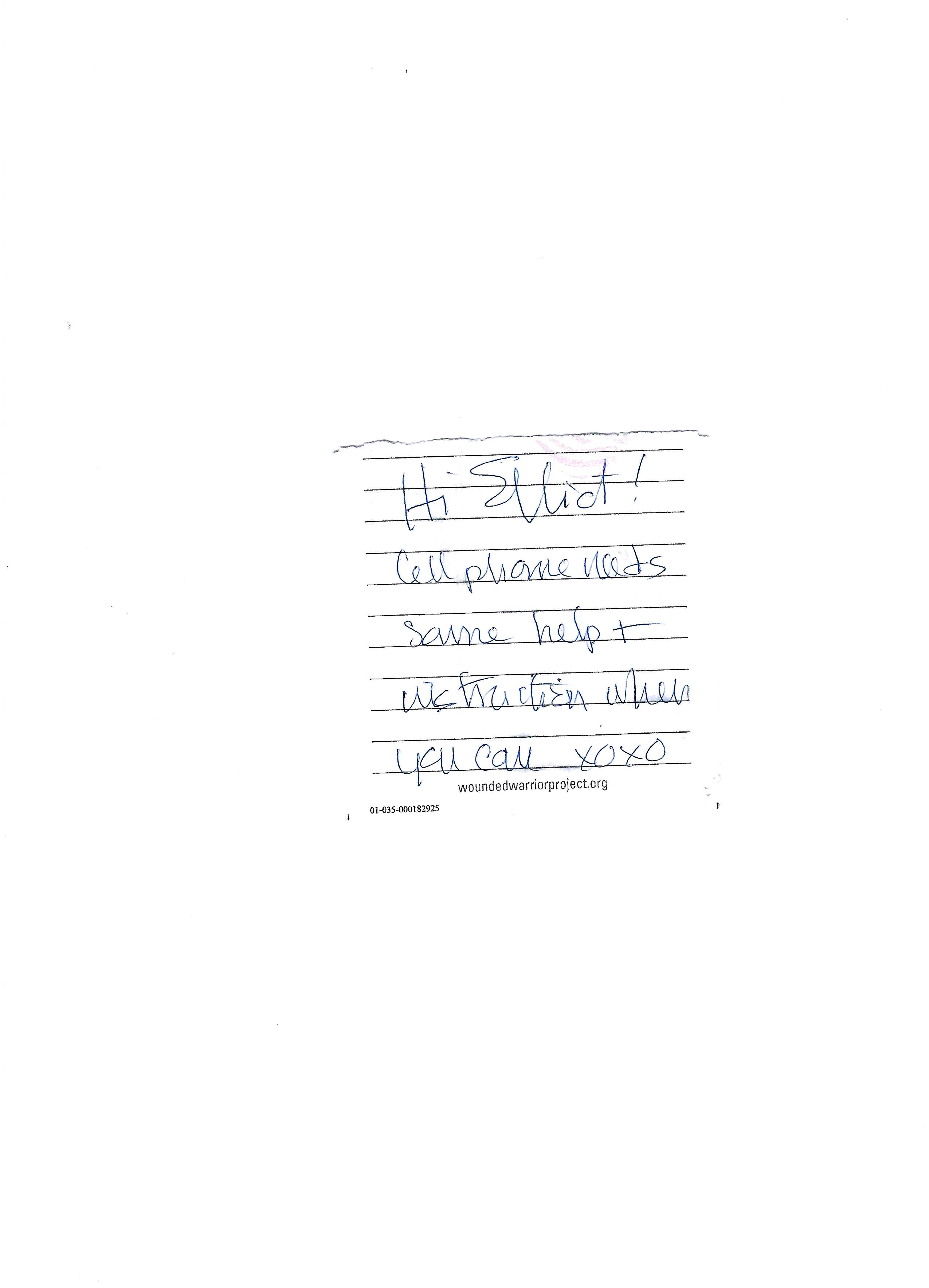

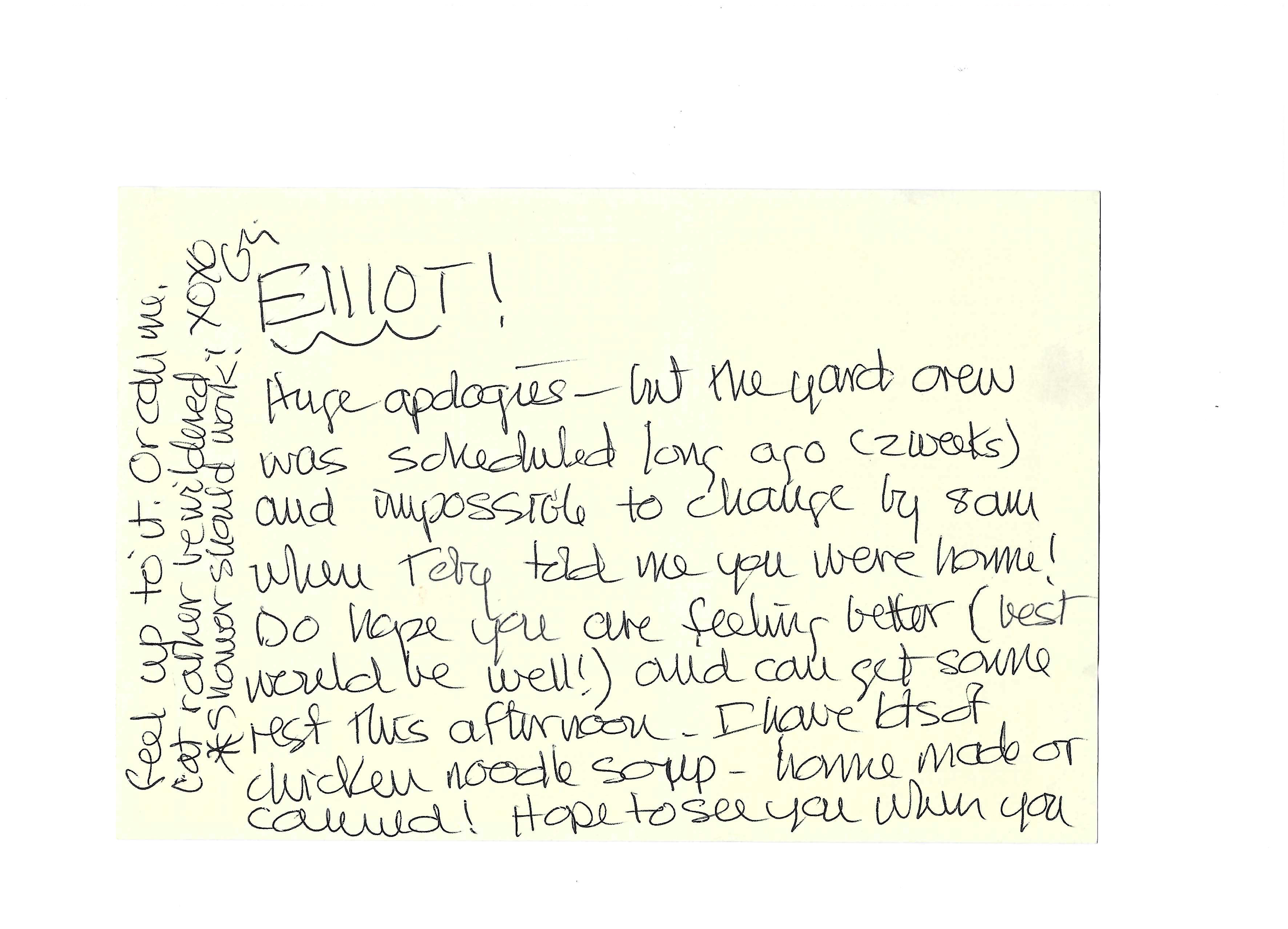

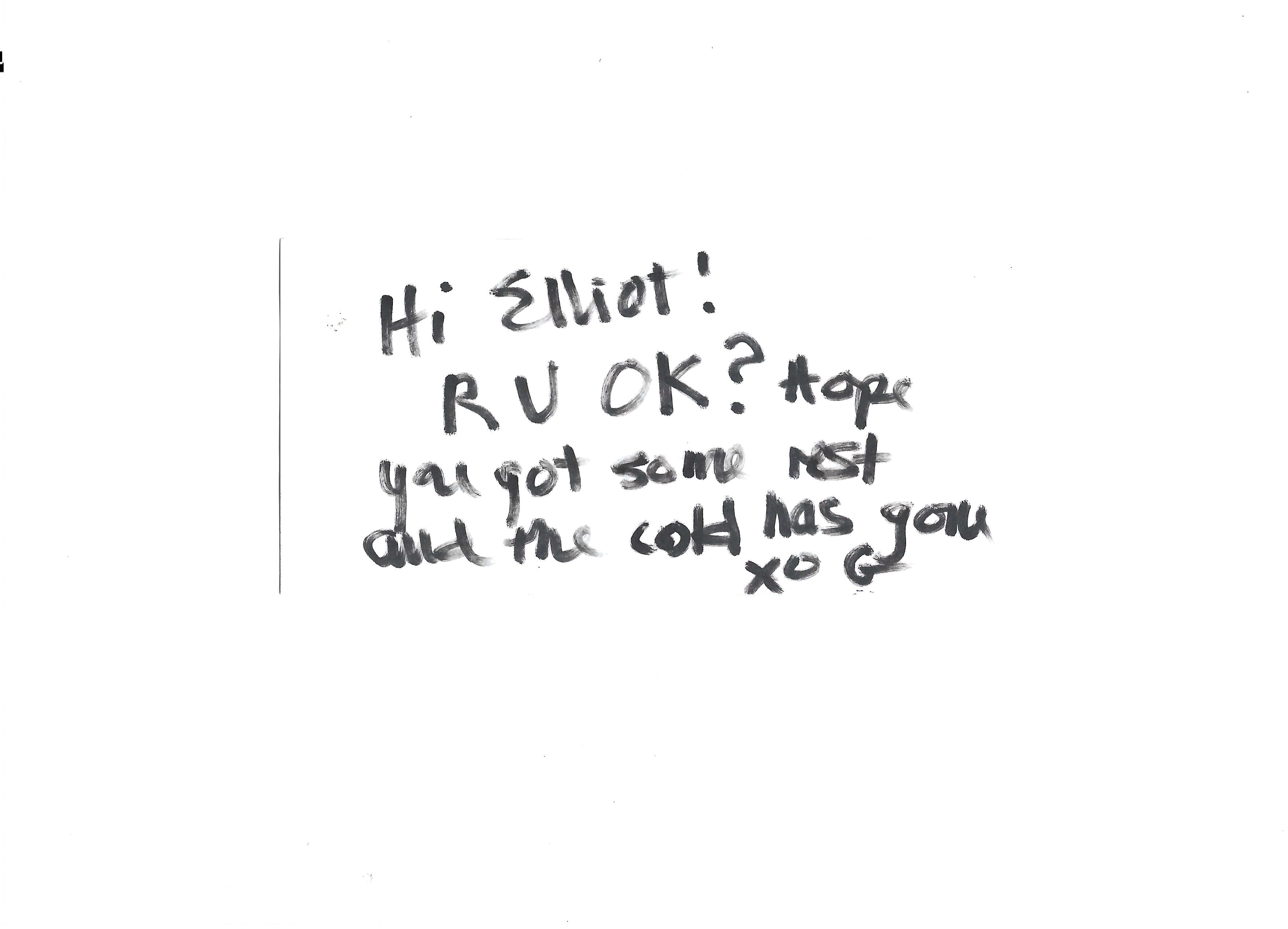

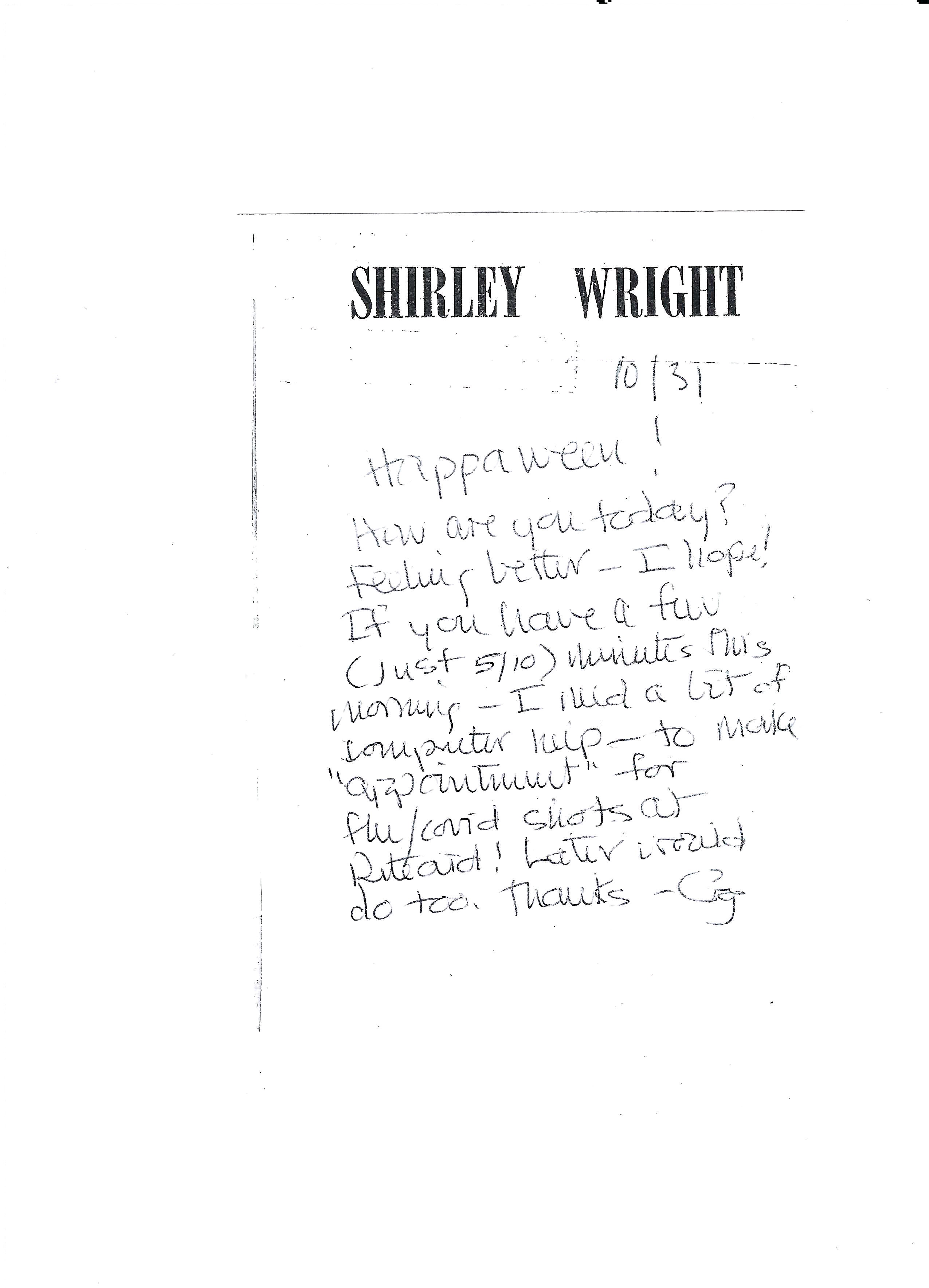

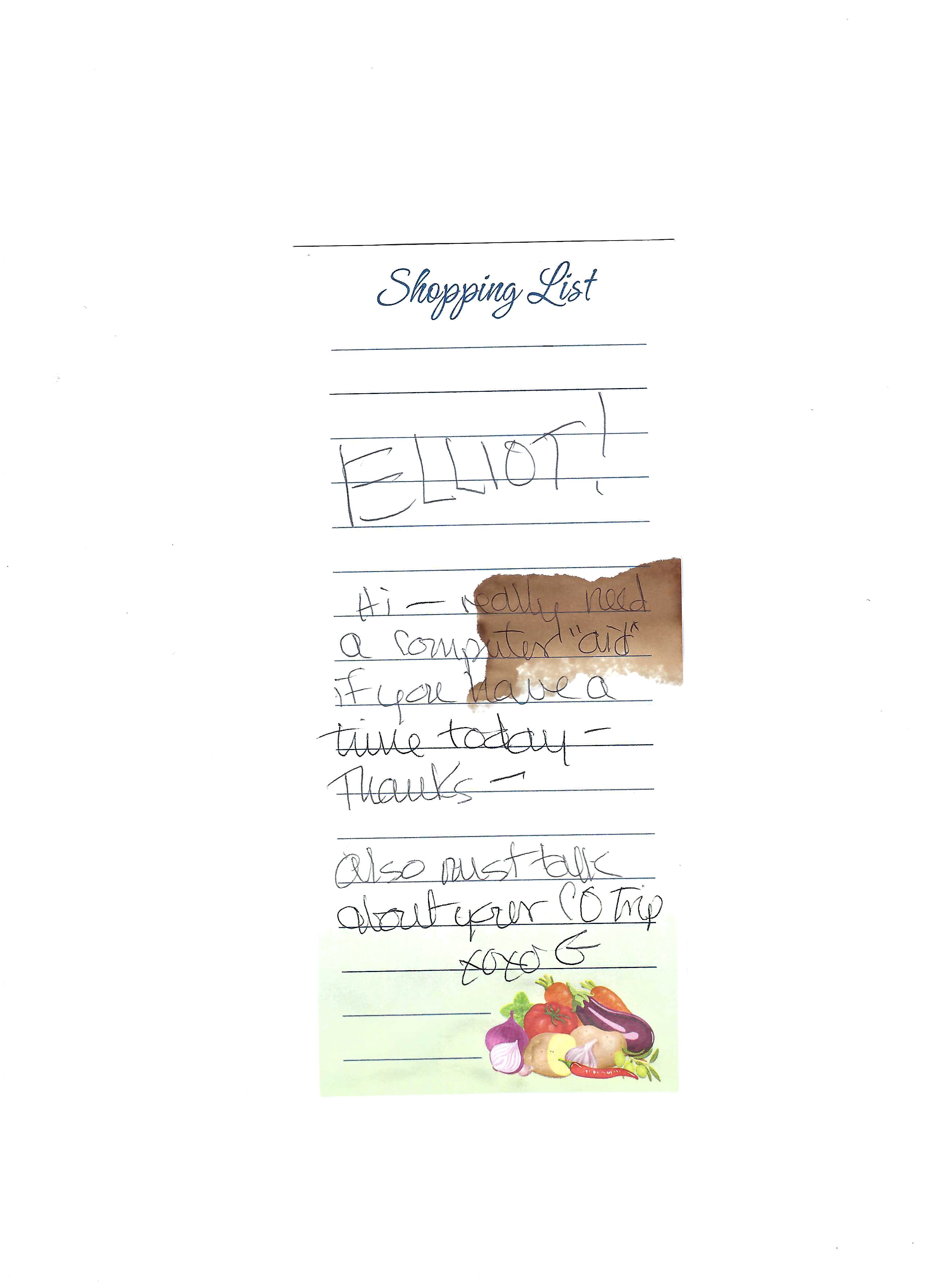

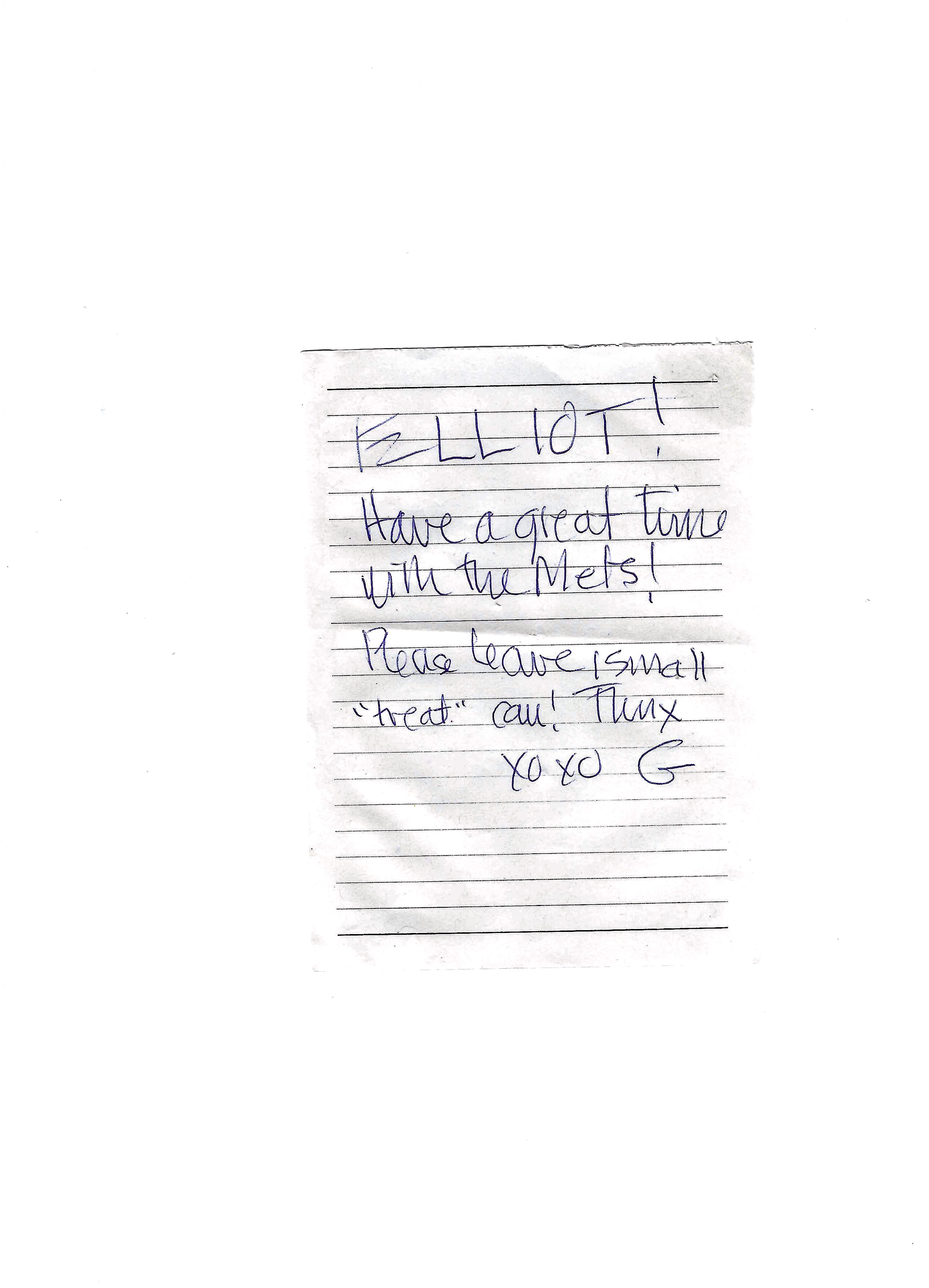

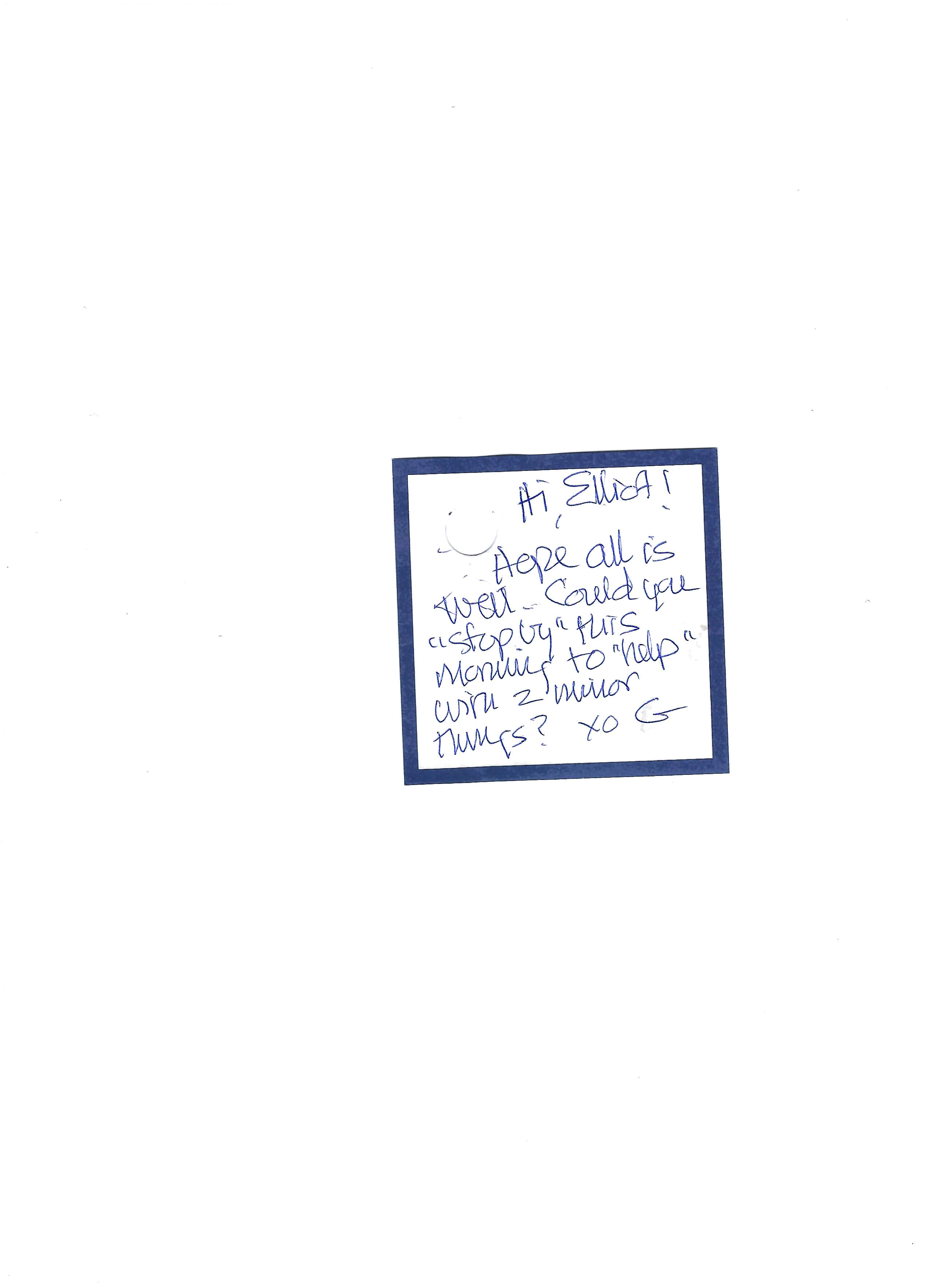

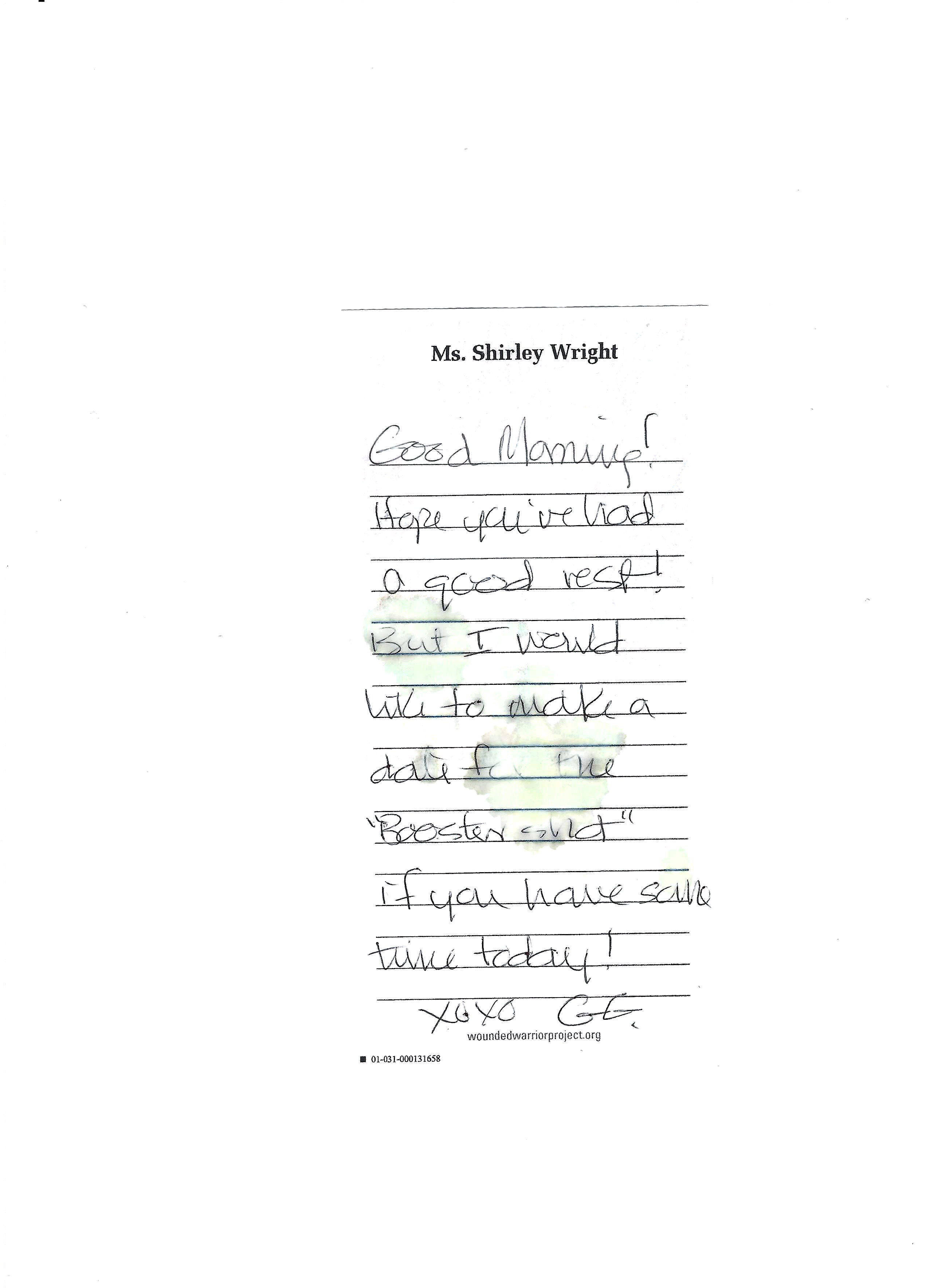

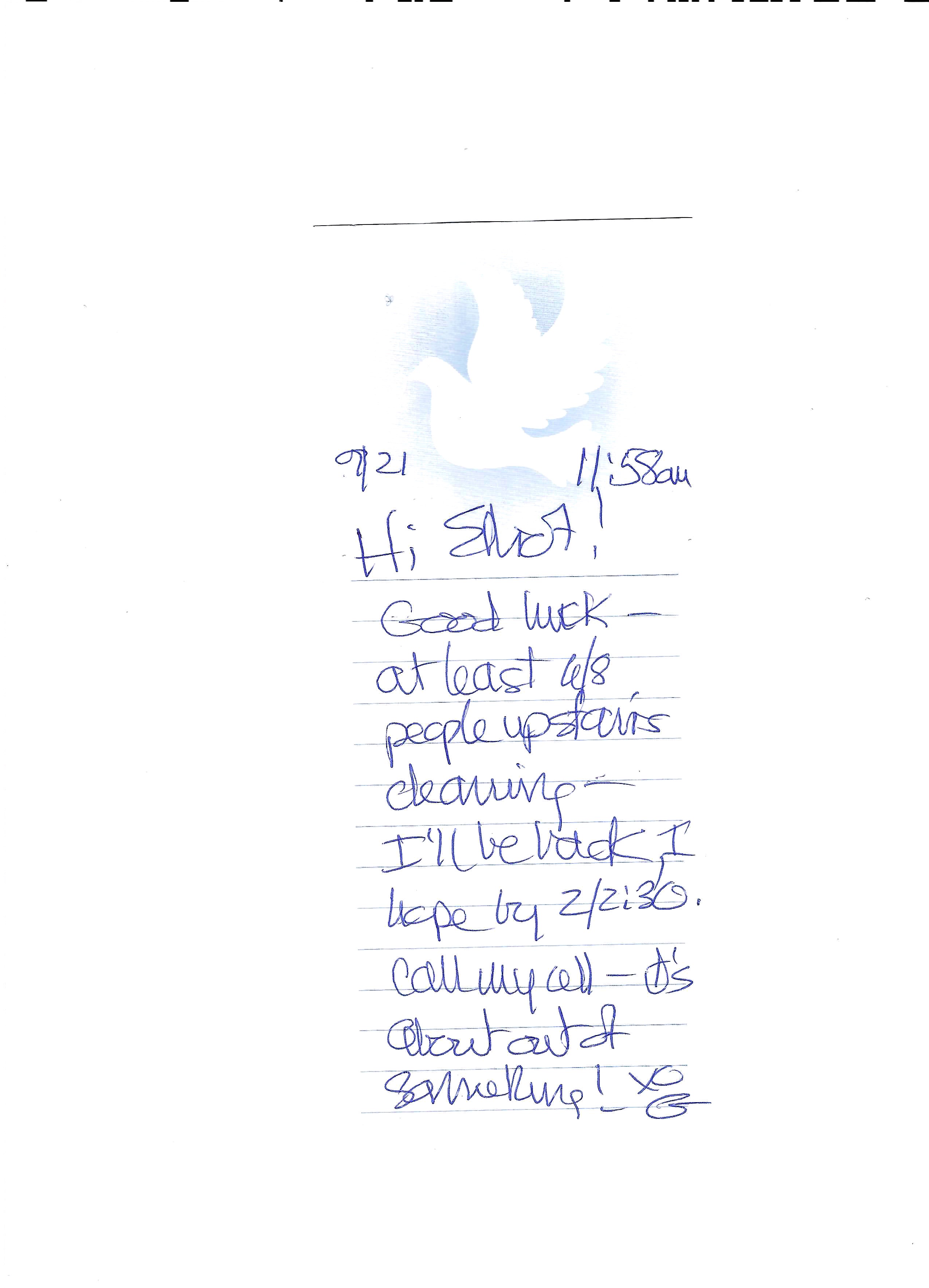

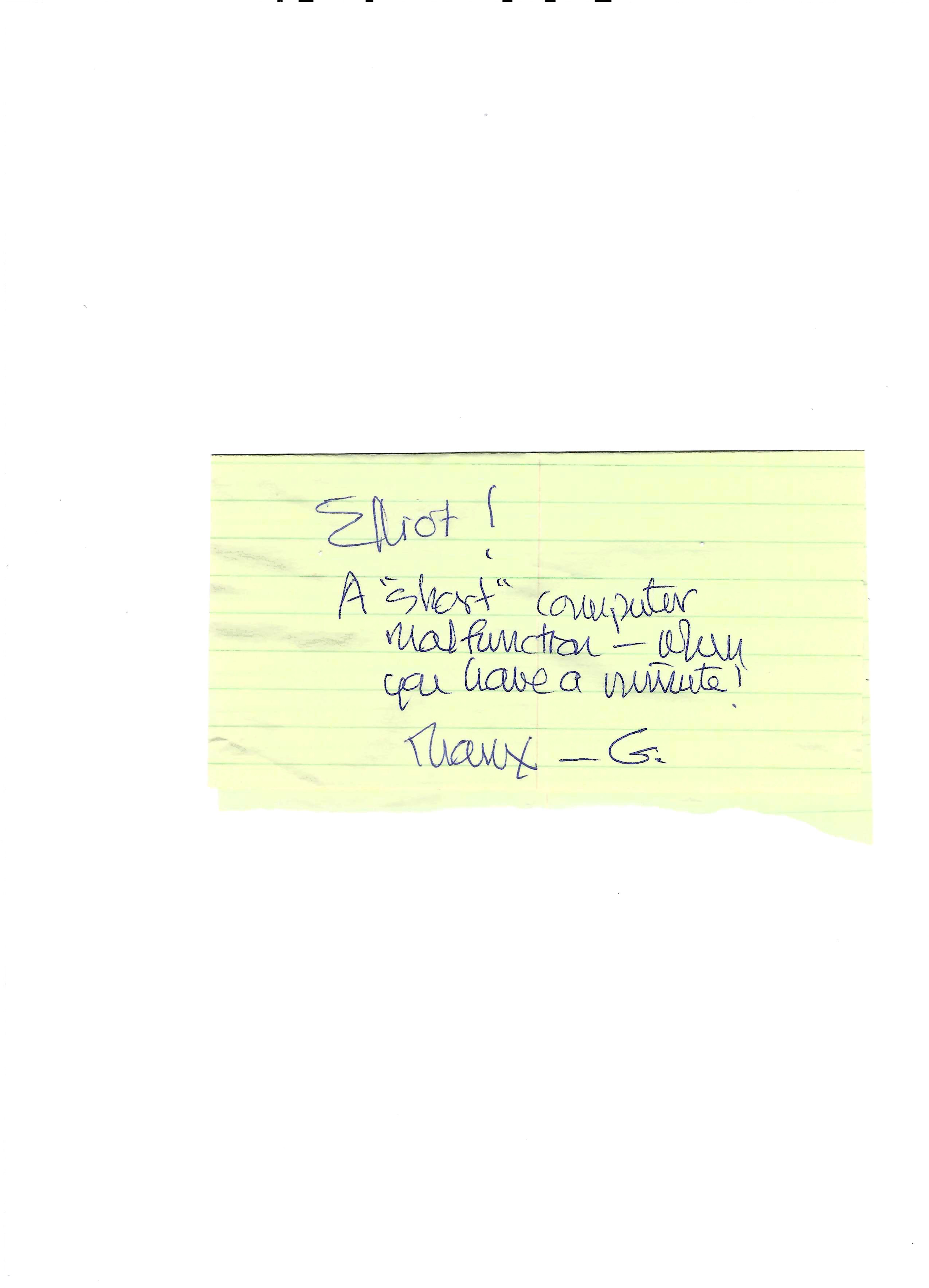

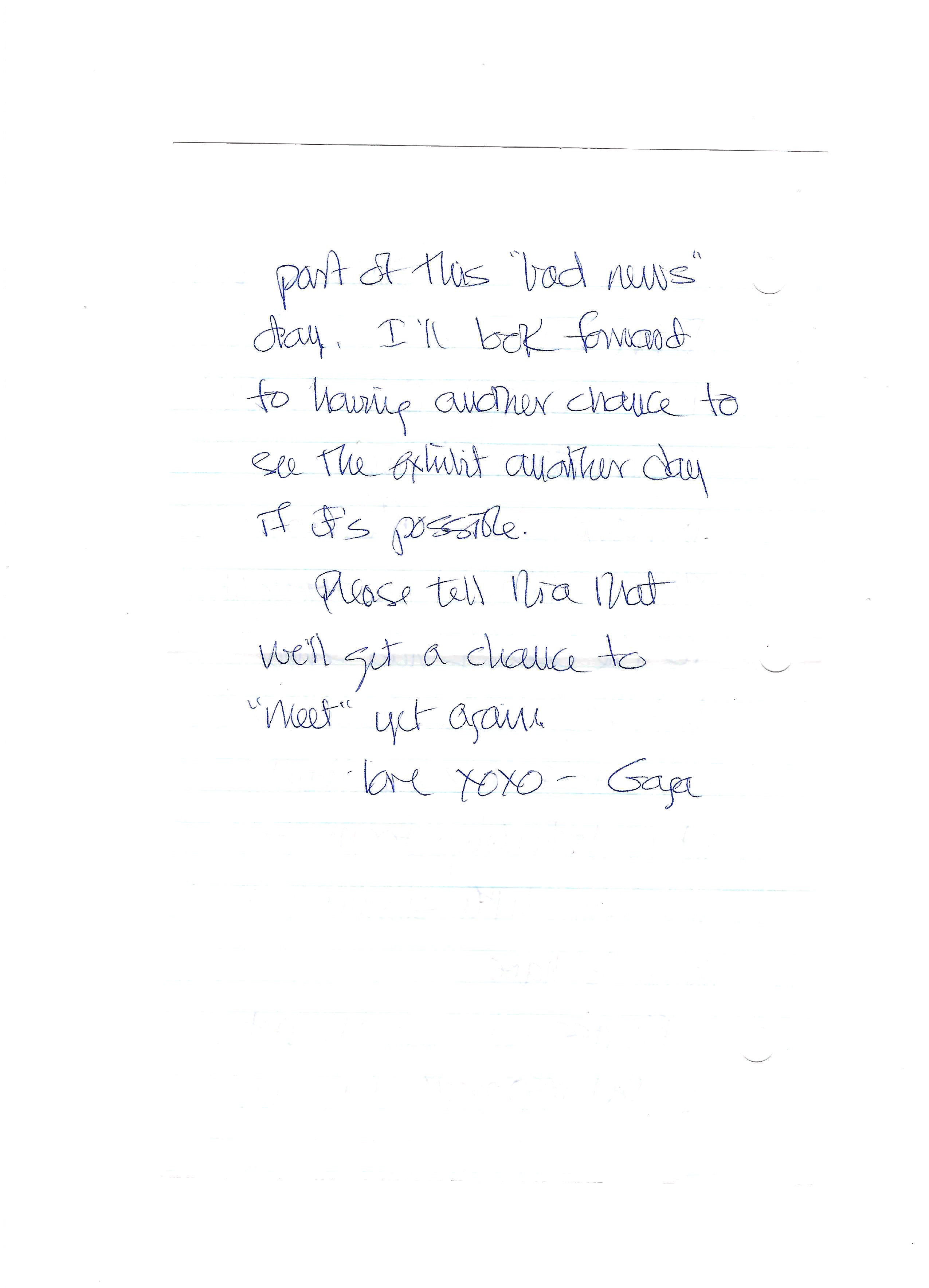

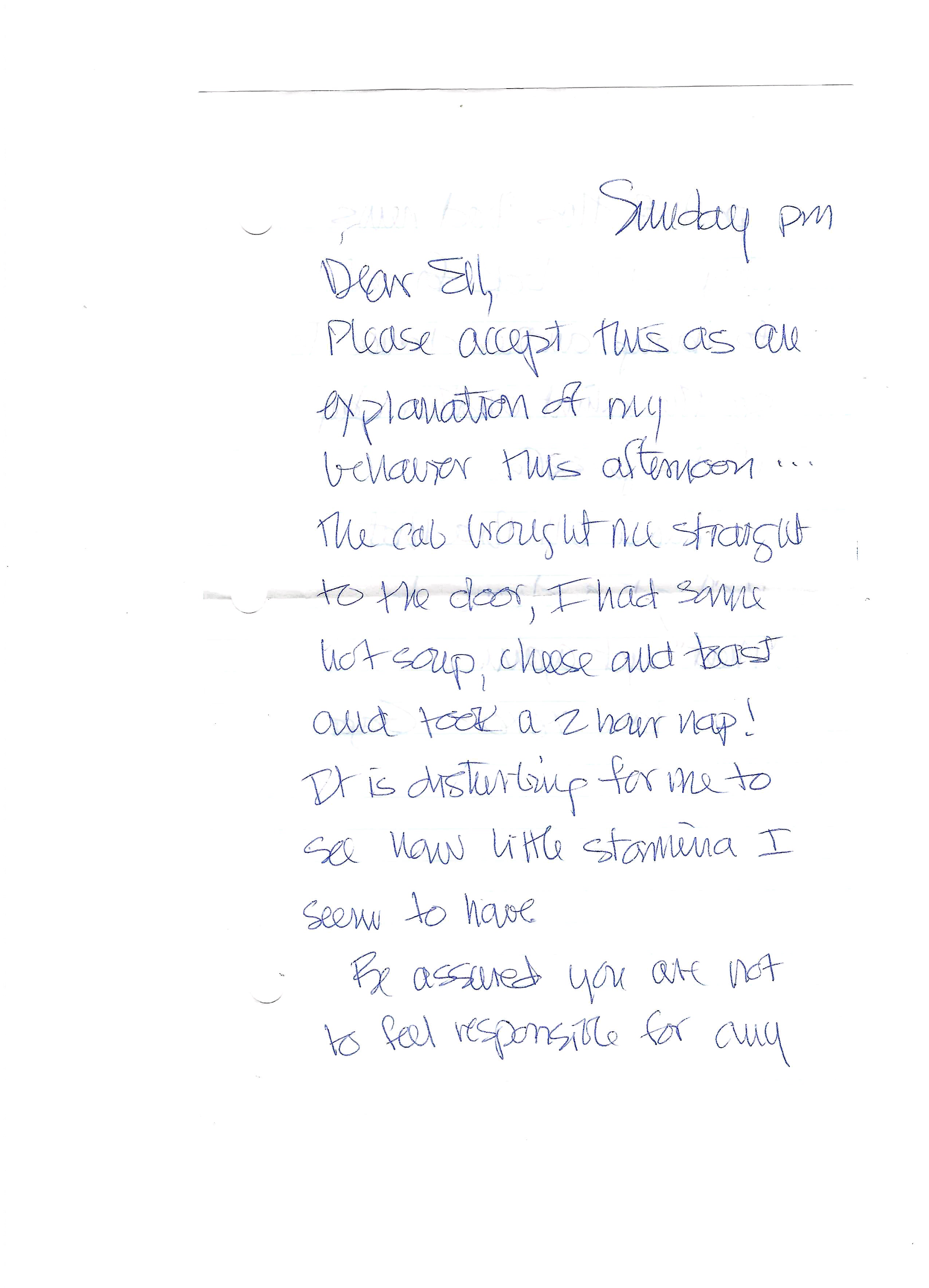

Notes of this nature—tentative requests scrawled in quasi-cursive—appear on my living room floor periodically. Their author is my ninety-five-year-old grandmother/landlord, Shirley. While lying catatonic in bed or perched in my office chair, I hear her gentle syncopated steps approaching my door followed by the soft woosh of the note being slipped underneath it. I am unbearably conscious of the fact that it is oh-so-easy to get up and open the door separating us, to reveal that I am home and awake and willing to assist with whatever is ailing her. Instead, I allow her footfalls to make their way back upstairs, for the note left in her wake to act as a mediator. I’ve received enough of them by now to identify a consistent formula:

- My name (Elliot or Ell or E)

- The mention of some sort of technical failure of the television and/or computer and/or cell phone

- Some variation of an apologetic plea

- A series of X’s and/or O’s

- Her name (Gaga or Gg or G)

The apologetic pleas, which define the character of these notes, include but are not limited to:

Check in when you can

Let me know if you might be available

If you get back this evening?

If you have a few minutes

If you have some time today

If you have a few (just 5/10) minutes

If you have some time before evening

If you have “some time” later

Do you have a minute?

Hope to see you when you feel up to it

Hope to see you when you have enough time and energy!

When you can

When you have a minute!

Could I please have a couple of minutes of your time before you go out?

Come up and/or call when you have time

Come on up when you feel like it—

Might there be time

If there’s time this evening

Just a minute?

On occasion, they are more overt:

Come see me!

And I do.

2.

A dizzy softness christens both her eyes, the left of which is milky white with blindness. Behind her, the cat devours the defrosting pork chop off the butcher block counter (wretched creature, she calls her sometimes—pretty girl, alternatively) while whatever indiscernible vegetable is on the stove slowly but surely burns. The surface of the dining room table is laminated with piles of carefully sorted papers: reports from Schwab for the son who will come to assist with the property taxes on Friday, charities soliciting donations with the promise of another calendar, T Magazine, bills to be paid by the daughter who’s in charge of the trust, The Met members newsletter, catalogs addressed to basement tenants long gone, et cetera. She teeters over to me, phone in hand. Oh Ell, I can’t seem to get this horrid machine to turn on.

This particular day and those like it are slipping rapidly by, and one of these evenings I’m going to have to confess—over our nightly glass of Seagram’s Gin on ice, no doubt—that I am going to move out. Looking at her in the kitchen shooing the cat from the counter, I find myself lapsing into a familiar yet deranged fantasy of my inevitable exit. Clutching her in my arms. Both of us are children. Both of us are crying. Saying something earnest and tragic along the lines of, I don’t want to leave. Tears. Overpacked boxes. Everyone watching. The fantasy runs headfirst into a brick wall once I try to imagine what comes next: her response, then the life that follows it. Departure is beyond the scope of my imagination. There is nothing comprehensible, nothing narratively satisfying, about an indisputable loss.

3.

When I was in second grade, my parents adopted a very gentle, very medium-sized dog named “Molly.” Molly was widely adored for her sweetness and ease, for the way she treated every child she encountered as if it were her own. As she aged, far outlasting her life expectancy of twelve or so years, she became deaf in both ears, then blind in one eye, then blind in both. My mother affectionately called her Hellen Keller.

Over our nightly glass of gin, my grandmother would occasionally ask: and how is our dearest Molly? The answer was always something like deaf, blind, and operating with a low cognitive capacity, but otherwise fine and relatively upbeat about the whole thing. Shirley would always respond with some variation of: my kindred spirit or just look at the two of us or you and me both, Molly.

When my mother had to put Molly down this last winter, my grandmother mailed her a brief hand-written note:

Dear Nancy,

Elliot has told me the recent story of Molly’s demise. I want you to know that I feel deeply for you—The passing of a beloved family pet. She was always a wonder to me in her calm, dear manner. I feel sad with all of you. But remember her as a happy friend with the children draped over her on the floor. You did the right thing!

All sympathy and best wishes.

Xoxo Love Shirley

My mother, who had divorced Shirley’s son nearly a decade prior, found this note humorously tender and filed it away in a folder full of other similarly significant papers.

4.

Last Thanksgiving, no one came to visit us and we went to visit no one, instead trundling off to some downtown restaurant for a seasonal prix-fixe menu. On the way back, bursting at the seams with it all, she free-associated on the buildings we passed while using my arm to steady her step. Jimmy Dodelson grew up there, that’s the pool I’d take your father to in the summer, my mother wanted me to move across from this park, we took you here when you were little and you loved the geese. The late afternoon sun licked the sides of our faces, blinding us both. I smiled down at her patient navigation of the sidewalk and allowed myself to believe, as I naively have for the last year and a half, that the whole thing would never end.

5.

The fact that I collect these notes at all indicates that I cannot fully commit to that delusion.