Wondering about the life of Langston Hughes

The Jangling of Dreams

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes is a black American poet.

Langston Hughes is

“an American poet, social activist, novelist, playwright, and columnist”

“one of the most important writers and thinkers of the Harlem Renaissance”

“one of the earliest innovators of the then-new literary art form jazz poetry”

In the blank spaces of a book, in the breaks of lines, this is Langston Hughes’s quest: to find a self within America, within color, within poetics, within personhood.

“I landed one cold winter afternoon in New York, broke and down on my luck. That night I went to Harlem. Luckily, my poetry caught on” — Langston Hughes (Guillén and Mullen 57).

[Place]

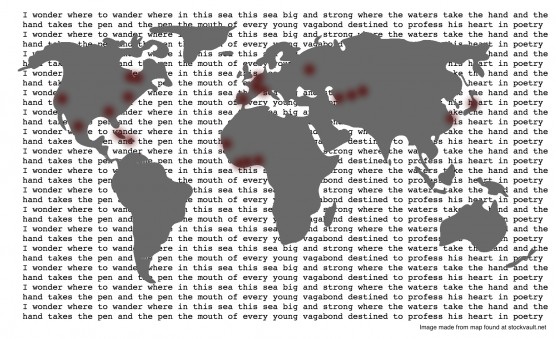

When we place someone into the folds of history, do we not make presumptions about where that person’s body is, what space it occupies, where it moves? And there is a power in such placement, a power to decide how a person’s physical existence is remembered and historicized. Langston Hughes, at the time of the Harlem Renaissance, is not living in Harlem. He is attending Lincoln University in Pennsylvania (Hughes, The Big 219), visiting New York on the weekends (Hughes, The Big 256). “The Weary Blues,” which would become the namesake of his first poetry collection, is written on a boat on the Hudson River (Hughes, The Big 92). It is winter, the winter right before Hughes is to board the ship to Africa, before he is to travel to Paris and Genoa, far before he is to finally enter Lincoln University and is to see the Harlem that is said to be in renaissance.

“Harlem is undoubtedly one of his great loves; the sea is another”

— Jessie Fauset in Crisis magazine’s review of The Weary Blues, March 1926

[Wonder]

Langston Hughes never wed, as far as we know. There is no mention of any lasting relationship in his lifetime (Rampersad xxi). We have wed him to poetry, the beat of jazz playing the procession, the smoky blues filling the room. It is a wedding conducted by many of Hughes’s critics, Margaret Larkin branding him the “proletarian poet” (Mullen 8), Carl Van Vechten calling him the “Negro Poet Laureate” (Mullen 71). Yet it is a wedding conducted again and again, postmortem. Today, we call him the poet of the Harlem Renaissance. But as with many things postmortem, this identification is rooted in memory. We remember Langston Hughes: poet. But what is it that we have forgotten?

Langston Hughes is a journalist. How could he not be? His twenties encompassed by both the Harlem Renaissance and the Great Depression, his thirties spent in the eve of World War II. And after, the last of his life spent in the rising social movements of the Sixties. In fact, some of Hughes’s earliest works of journalism are written while he is abroad during the 1930s, in Russia, Japan, China, Spain. Perhaps it should occur to us that Langston Hughes does not just belong to American Literary History. He belongs to the world stage.

[Represent]

If Langston Hughes aims to represent the lives of black Americans by fusing their collective experiences with his own (“Langston Hughes,” Poets.org), is this then his identity, somehow simultaneously the self but also the greater self that exists within the collective life of a people? And how to represent a people in a country where racial views, tensions, and presumptions change by the decade?

Think upon America.

America: the amalgamation of the world’s blood.

And yet, history has a shadow long as the rolling of the hills, wide as the fields that bare their produce to the waning sun.

America: bloodied; amalgamation of free and unjust

How to write America, its history so often unspoken but not to be forgotten.

The Negro Speaks of Rivers by Langston Hughes

To use language is to be of society. For, language is the tool of interaction and communication. According to Mikhail Bakhtin, even inner speech “is completely dialogic, totally saturated with the evaluations of the possible listener or audience, even if the speaker has no idea whatever of this listener” (Bakhtin 118). And to be of America is to be of the public eye. Perhaps, Langston Hughes sits to write a poem. The room is still and empty. Sunlight makes no sound as it traverses the windowpane. But on the streets, there is a tide of voices, rushing above and under each other, calling cross the shores of sidewalk. In which milieu does a poem live?

[Remember]

Hughes wrote no further autobiographies after I Wonder as I Wander. In fact, according to Edward Mullen’s Critical Essays on Langston Hughes, a collection of reviews of the writer’s works, “Faith Berry’s Langston Hughes Before and Beyond Harlem (Westport, Conn.: Lawrence Hill, 1983) is the most complete biography to date. Although it is not a complete study, since it traces Hughes’ career only up to his permanent move to Harlem in the 1940s…” (4). Hughes lives until May 22, 1967 (“Langston Hughes, Writer,” par. 1). Finding his life in these 27 years in between is like trying to weave a canvas.

[Desire]

In 1926, Hughes publishes The Weary Blues. The public adores it. In 1927, he publishes Fine Clothes to the Jew. It is criticized for focusing heavily on the poor black in America (“Langston Hughes: a Biography”). How to live in the public, to be the public? Discord rests in what the public desires and what the public is. When Hughes publishes Montage of a Dream Deferred in 1951, the civil rights movement is soon to surface. What is it that the public wants?

Langston Hughes on the Challenge of Earning a Living as Black Writer

Langston Hughes

“16 volumes of poetry, two novels, three short story collections, 20 plays, novels, essays, historical works, musical shows” (“Langston Hughes: a Biography”). But who is Langston Hughes?

Who is America?

“My greatest ambition is to be the poet of the Blacks. The Black poet. Do you understand?”

— Langston Hughes

(Guillén and Mullen 56).

Works Cited

Bakhtin, M. M. “Literary Stylistics.” Bakhtin School Papers. Oxford: Oxon, 1989. 114-129. Print.

Emanuel, James A. Langston Hughes. New York: Twayne, 1967. Print.

Guillén, Nicolás, and Edward J. Mullen. “Conversation with Langston Hughes (1929).” Afro-Hispanic Review 9.1/3 (1990): 56–57. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

Hughes, Langston. The Weary Blues. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1945. Print.

Hughes, Langston. I Wonder as I Wander. 2nd ed. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993. Print.

Hughes, Langston, and Christopher C. Santis. Langston Hughes and the Chicago Defender: Essays on Race, Politics, and Culture, 1942-62. Urbana: U of Illinois, 1995. Print.

“Journalist.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

“Langston Hughes.” America’s Story from America’s Library. Library of Congress. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

“Langston Hughes.” PoemHunter.com. PoemHunter. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

“Langston Hughes.” Poets.org. Academy of American Poets. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

“Langston Hughes.” Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

“Langston Hughes, Writer, 65, Dead.” On This Day. The New York Times Company, 23 May 1967. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

“Langston Hughes: A Biography.” Cora Unashamed. PBS. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

Langston, Hughes. The Big Sea: An Autobiography. 19th ed. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993. Print.

Mullen, Edward J. Critical Essays on Langston Hughes. Boston, Mass.: G.K. Hall, 1986. Print.

Rampersad, Arnold. “Introduction.” I Wonder as I Wander. 2nd ed. New York: Hill and Wang, 1993. Xi-xxii. Print.

“Self.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Web. 18 Dec. 2015.

Audio Files

“The Negro Speaks of Rivers” by Langston Hughes. From Langston Hughes in Lawren. “KAW River Bridge.” SoundCloud.

“Langston Hughes on the Challenge of Earning a Living as Black Writer (1957).” From WNYCRadio. SoundCloud.

Images

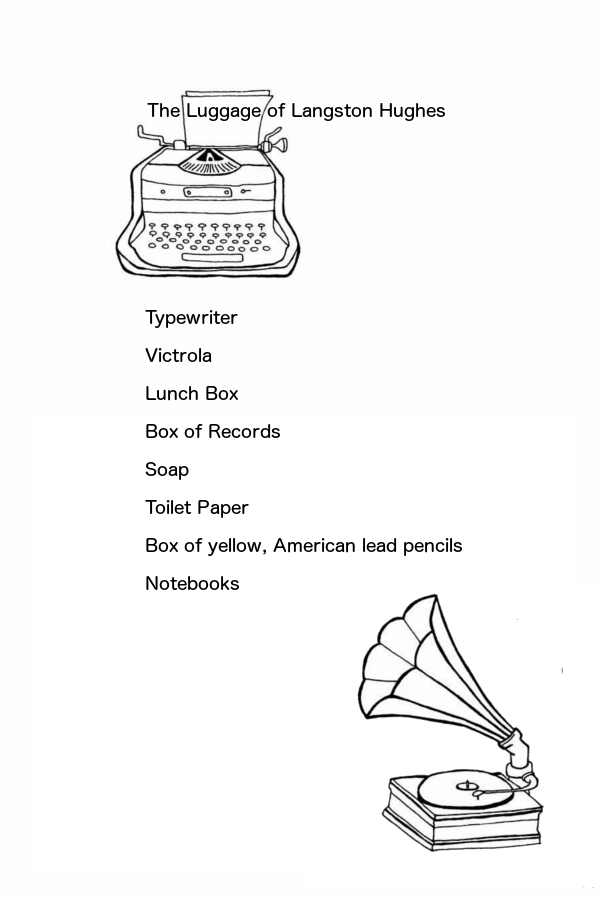

World map image made from map found at Stockvault.net

Victrola and Typewriter by Susan Xiao

Weaving picture made in Gimp

![[1]](/assets/11.jpg)

![[2]](/assets/2.jpg)

![[3]](/assets/31.jpg)

![[4]](/assets/41.jpg)