The Materiality of Loss and Growth, or, to be haunted in the name of a will to heal.

Waters

The Materiality of Loss and Growth

or, to be haunted in the name of a will to heal.

the ghosts in the well

It was my first chosen home—the first house that became mine out of deep intention and investment. Over the course of two years, roommates filtering in and out, its walls became thick with layers: I chose and re-chose colors, drew murals and painted them over, scribbled dreams or stories in chalk and washed them away. I built and re-built each room with an evolving array of furniture, and learned to love every floorboard with care.

My two best friends betrayed me in that place.

The walls I had painted closed in.

My best allies became strangers, and I did not recognize my home.

I came to know a place called “the well.” It’s a sense of enclosed darkness, an undeniable and unchosen solitude; there is only room for one, and the hands that hold the door shut are both invisible and deaf. Reminiscent of Freud’s melancholia, it is “a mourning without end, [resulting] from the inability to resolve the grief and ambivalence precipitated by the loss of the loved object, place, or ideal” (Eng and Kazanjian 3). The well paralyzes and silences; it is where we wake up after falling long and hard from the tightrope of linear time, when loss or trauma disrupts any hopefully imagined illusion of logic or causality—when something familiar or loved has suddenly become irrevocably strange.

In the introduction to their compilation Loss, David Eng and David Kazanjian complicate Freud’s understanding of melancholia, suggesting its capacity for use as a creative and empowering tool in the vein of historical materialism: “By engaging in ‘countless separate struggles’ with loss, melancholia might be said to constitute, as Benjamin would describe it, an ongoing and open relationship with the past—bringing its ghosts and specters, its flaring and fleeting images, into the present” (Eng and Kazanjian 4). The word “engage” marks the difference between this historical-materialist melancholia and being stuck in the well; it is to acknowledge and remember whole-heartedly: I have been to the bottom of the well, and only through the act of clawing my way out have I come to know the contours of my loss—and I have come to survive. Melancholia can only become creative through the desire for a healing that does not forget, in committing to the climb knowing full well that we may only see the sun in glimpses, and we may only know the structure of our world by the dirt under our nails—but that in these fragmentary “remains” exists the possibility of redemption. It comes from the “willingness,” as Avery Gordon calls it, “to follow ghosts”:

neither to memorialize nor to slay, but to follow where they lead, in the present, head turned backwards and forwards at the same time. To be haunted in the name of a will to heal is to allow the ghost to help you imagine what was lost that never even existed, really. That is its utopian grace: to encourage a steely sorrow laced with delight for what we lost that we never had; to long for the insight of that moment in which we recognize, as in Benjamin’s profane illumination, that it could have been and can be otherwise (Gordon 57-8).

Imagining a flooded home illuminates both Eng and Kazanjian’s sense of “remains,” and Gordon’s of haunting. Inscribed in the mess of water damage are representations of the past, and proof of trauma; simultaneously, the flood implies a future of redemption, newness, and rebirth—but only as a consequence of destruction. This simultaneous attention to past, present, and future is crucial to both creative melancholia and historical materialism; in both, the past as vitally present. The flooded home represents an embodiment of haunted remains.

In 2010, my basement bedroom flooded; in 2014, it was my home.

after the flood

You start with the floors. Hands and knees, you scrub away the dirt. Smooth away the scratch marks from their bed frame. Take your fingernails to the rubber scuffing from their shoes. Lift the rugs, and gather the dust. Fill the cracks between the floorboards, and shine them until you can recognize the reflection in their gleam as yours.

Then you paint the walls. Over their chalkboard lists, their murals, and their love poems; over the navy blue, over the fake marble texturing, over the yellow wallpaper. Don’t add water; keep the white paint thick. Lean into the roller, and push the layers across the walls’ uneven face. You want to cover their trace.

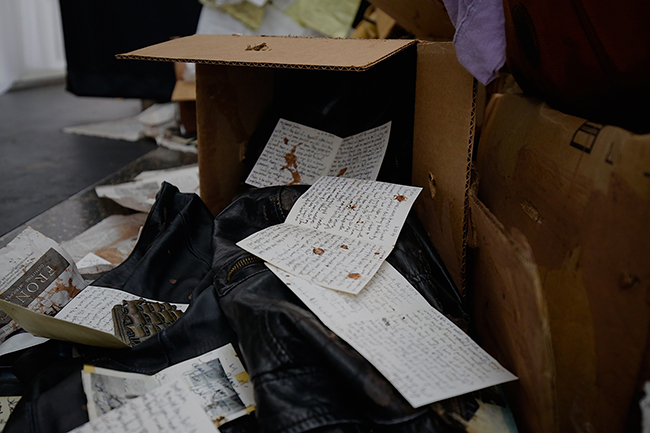

Next are the clothes—piles and piles of garments you cannot wear, or are not yours. You know the shape of their bodies by the space their clothes take up. You feel their absence in the empty armholes, the open belt loops; you feel their skin on the unwashed fabric. In your own coats, you feel the shadow of their heat. You throw most of it away, but the feeling remains.

You know the books will hurt. In the marginalia, you see the echo; ghostly script runs and blurs with the printed ink. Resist the urge to set them aflame; ashes will do you no good. Turn each page with care, and listen. Each text an index of voices: “…the whole background of an item adds up to a magic encyclopedia whose quintessence is the fate of his object,” and yet— “the acquisition of an old book is its rebirth” (Benjamin 60-1). Turn the page; do not turn away. Read each book, and touch its former lives.

Last, you open the drawers. Empty the stacks of journals onto the floor. Each contains a ghost, a version of yourself you’d almost succeeded in forgetting—but forgetting is not why you’re here. Do not purge; the ghosts don’t need these words to survive, but you do. So re-visit the ebb and flow of your voice—remember that once, you could speak. Find the dates you’ve forgotten, and read the words aloud. Summon the specters, and open your eyes.

It is time, once again, to come alive.

crawling out of the well

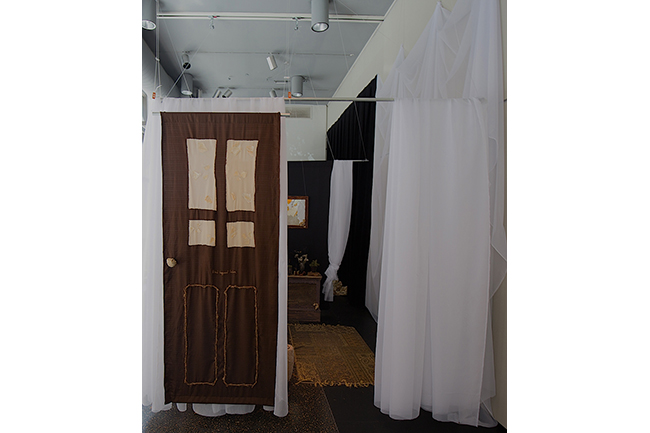

Building the installation WATERS and composing its accompanying short story was an act of engagement, animating my loss and reckoning with my memory. To dive into this wreck was an act of survival, summoning my ghosts with a will to heal, but “it is no simple task to be graciously hospitable when our home is not familiar, but is haunted and disturbed” (Gordon 58).

I begin with the living room: it is the embodiment of refusing to open the basement door and bear witness to the proof the flood. In the short story, the living room provides the opening scene, where the protagonist falls asleep instead of confronting the water downstairs. It is the space of repression and neglect; of being unwilling or unable to access, know, or acknowledge the past.

The muted television loops the same images: dirty, foaming water drags street signs, mobile homes, and whole trees down highways. The archival black and white footage (a fragmented and anonymous memory) asserts the presence of the past in flashes, projected onto a curtained wall. You must enter the room immersed; you are here to make space for death.

Take a knife to the couch upholstery. Split it wide for the brittle stems of cattails, and be patient as they snag and resist. Wind the vines of dried yellow flowers around the wooden legs. Arrange the dead plants, frozen with leaves half-curled, that they brought home and never remembered to tend.

(and in recreating paralysis, I am stretching my legs)

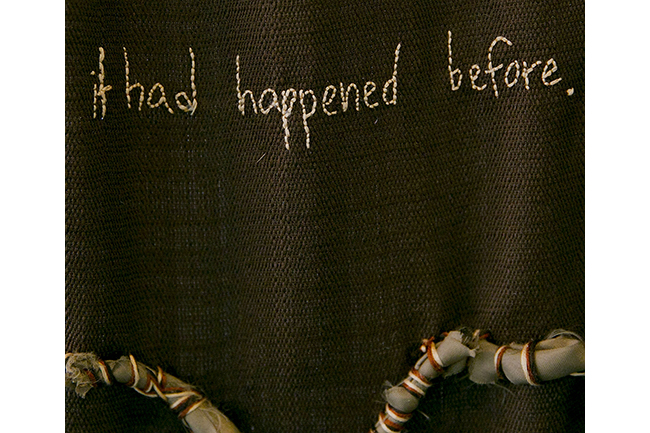

To build the flood, you must re-destroy. Fragments of your writing on scraps of paper; legal pads thick with wrinkles and creases; journals, journals, and journals full of your past selves—irrevocable evidence—and letters in your own script. Left behind. They left behind every trace of your voice—unheard, unreceived, shouted into a void. You encounter your own echo.

This time, everything is subject to the water; nothing will be spared. Wet your brush with paint, dirt, water, tea, and begin to pour. Everything drips, everything is absorbed.

Drenching the pages, boxes, and clothes, I am “pushing back forgetfulness.” It is a revisitation, an intervention. As I wet the objects indiscriminately, it is a reenactment; but each drop of water is chosen. In reliving loss, creative intention liberates the remains from their origin. There is both an active engagement with memory, and there is hope. Each pour is like language as it flows in the most satisfying of writerly moments: wholly new, and urgent in its precision in capturing something fleeting or absent—and yet true.

Writing: a way of leaving no space for death, of pushing back forgetfulness, of never letting oneself be surprised by the abyss. Of never becoming resigned, consoled; never turning over in bed to face the wall and drift asleep again as if nothing had happened; as if nothing could happen (Cixous 3).

In the privacy of my creative process, I began to find the syntax and rhythm of my own voice. Watering my belongings was a confrontation of the abyss; and although the recognition was incomplete, I knew the voice to be mine. The final installation cannot reflect the joy in this discovery. But maybe I’ve always written…because of disappearance. To confront perpetually the mystery of the there-not-there (3).

In digging up graves, forcing the ghosts to take up space, I discover seeds—newly sprouting, beginning to take root.

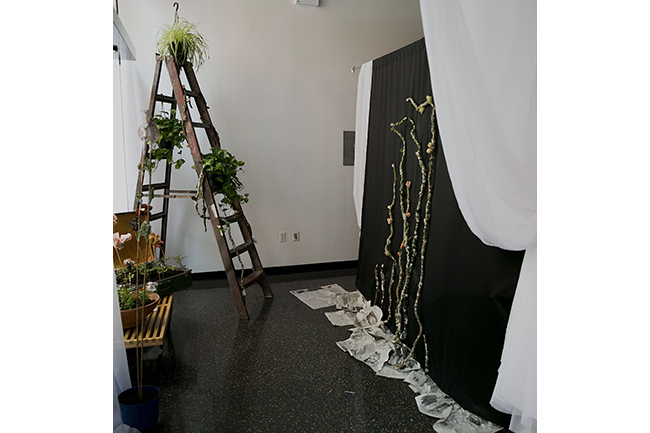

the garden

Like the essays in Loss, my narrative installation attempts to “explore the numerous material practices by which loss is melancholically materialized in the social and cultural realms and in the political and the aesthetic domains” (Eng and Kazanjian 5). In the living room and the basement, I recreated the materiality of the experience of loss; in the garden, I put the remains into practice as seeds, whose roots are inevitably bound to the soil of this place, but whose blooms are entirely new. The darkness of confronting—of “looking loss in the face,” of intimately knowing, feeling, and remembering the bottom of the well—gives way to a sunlight that does not blind. The basement thrives behind me, ghosts made legible in every page, box and sleeve. “Haunting raises specters, and it alters the experience of being in time, the way we separate the past, the present, and the future;” to allow or make space for haunting means the basement cannot fade away, cannot cease to exist (Gordon xvi). But the garden is where the loss no longer dictates the only meaning of remains—where remains become the materials of growth, neither because or in spite of their past. It is where I begin to speak.

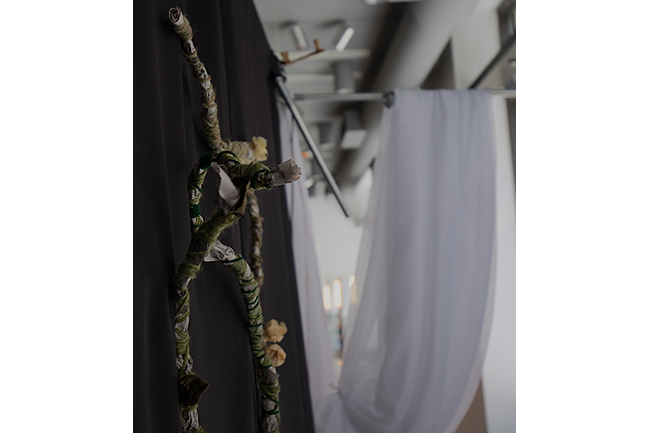

Shirts, skirts, and dresses: left behind, becoming yours. Cut, pin, sew, wrap—newspaper, cardboard, pages, scraps of fabric…everything is coming alive, becoming vines. All the plants you’ve been watering since they left, the plants whose bright leaves have everything to do with you, mingle with the paper and fabric flowers. Tear and sew old shirts into petals; embroider worn-out pants into leaves. Roll and twist newspaper, encircle it with yarn; around and around and around, the cathartic repetition a reflection of time spent.

The hope engaged through my creative process is an “enactment of the critique function,” which “[thinks] beyond the narrative of what stands for the world today by seeing it as not enough” (Duggan and Muñoz 278). It is a political hope, taken up in refusing the narrative which would include me in the list of remains, and which would narrate my attention to the past as wastefully stagnated melancholy. It assumes that my engagement with personal loss is simultaneously an attention to collective loss—a mourning both mine and not mine. In witnessing the rupture of a narrative which encircled and overarched my sense of self, I encounter the limit of normative thinking around loss which either accepts trauma as inevitable (“it was meant to be”) or logical (“everything happens for a reason”); it opens into a newly hopeful plane, full of “steely sorrow laced with delight” in recognizing the infinite ways it could have been, but was not (278).

It is not only that “the personal is political,” in the sense of claiming individual experience as inherently politically entwined with collectivity or structural loss; it is the hope that Muñoz’s sense of “revolutionary consciousness” can be a source of power not only in the traditional (public) realm of political engagement, but also in the intimacy of our homes and the privacy of our own and sorrows (278). The materials of my past are vitally present in the fabric, the newspaper, the pages of books that make up the materials of the garden—but they do not dictate what they become. “This attention,” as Eng and Kazanjian put it, “…generates a politics of mourning that might be active rather than reactive, prescient rather than nostalgic, abundant rather than lacking, social rather than solipsistic, militant rather than reactionary” (Eng 2).

Because you cannot turn away. Sow the seeds lovingly, and cover them in soil—but the garden will not tend itself. Do not forget the well. The torn fabric sewn into blooms, the newspaper curling under the basement walls—you must build the garden alongside their testimony of the past. Let the wires climb among the ivy, sewn leaves reaching for sun. Cultivate the possibilities of what remains.

And the past is necessarily a source of strength; the sun has never felt so bright as upon emerging from the well. In this historical moment, the shadows of imperialism and capitalism loom ever darker, threatening to blot the truth of our most violent pasts and present, and narrating loss as an inevitable sacrifice to the causal gods of progress. If we want to survive, we must draw upon our knowledge of the darkness in order to keep the sun in sight—while we march and organize, while we fight and bleed, while we mourn and heal.

Do not turn away, do not be ashamed. Let us emerge from the basement knowing that it still exists. Let us enter the garden, and haunted in the name of something-to-be-done.

Works Cited

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Ed. Hannah Arendt. Trans. Harry Zohn.“Unpacking My Library,” “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” and “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968. Print.

Cixous, Hélène, and Deborah Jenson. Coming to Writing and Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1991. Print.

Duggan, Lisa and Muñoz, José Esteban. “Hope and hopelessness: a dialogue.” Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory Vol. 19, No. 2, July 2009, 275–283.

Eng, David, and David Kazanjian. “Introduction: Mourning Remains.” Loss: The Politics of Mourning. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U of California, 2003. 1-27. Print.

Gordon, Avery. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota, 1997. Print.

Lahiri, Jhumpa. “A Temporary Matter.” Interpreter of Maladies: Stories. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2000. 1-22. Print.

Morrison, Toni. The Bluest Eye. New York: Plume Book, 1994. Print.