A VR Exhibit for “The Man with the Compound Eyes”

What We Will Remember

A VR Exhibit for The Man with the Compound Eyes

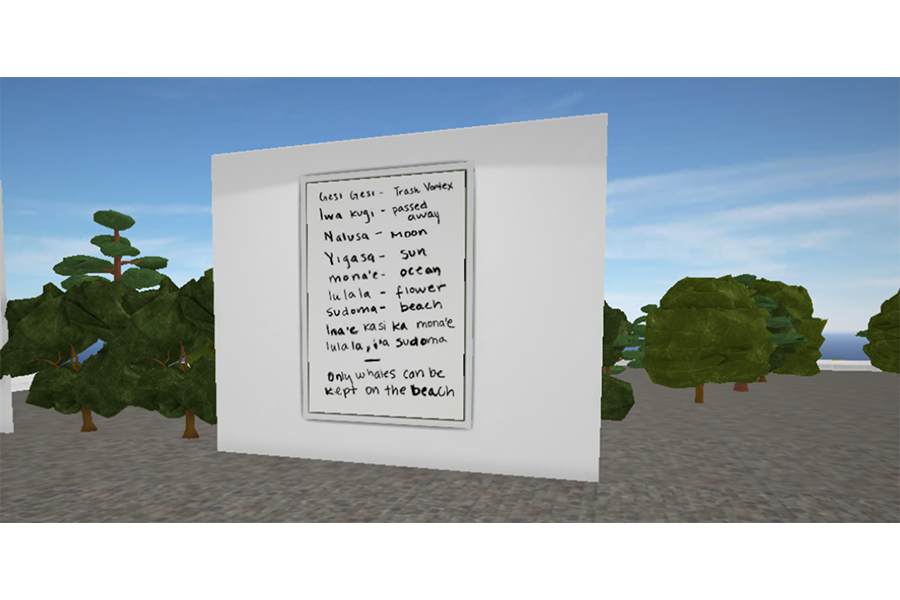

In the novel The Man with the Compound Eyes, author Wu Ming-Yi adds a layer of mysticism to a world that mirrors the realities of our own. The characters in this novel cannot avoid disaster, and neither can we. While the trash vortex of the novel is fictional, disaster has still manifested itself in forms such as earthquakes, wars, and floods, wreaking similar effects. In many instances globally, post-disaster situations call for a massive redevelopment scheme in order to urbanize a destroyed landscape and quickly return to “normal.” Such has been the case throughout China, where after earthquakes in Sichuan, Lijiang, and Tangshan, the environments were rapidly developed to boost the economy.1Similar patterns have emerged in areas that were affected by the construction of the Three Gorges Dam.2In each of these situations, cultural heritage was utilized in a strategy for economic development, and these traumatized environments were quickly subject to a method of “touristification,” a “process of relatively spontaneous, unplanned, massive development of tourism, which leads to the transformation of a space into a tourism commodity itself.”3

In The Man with the Compound Eyes, residents of the coastal Taiwanese town of Haven face the impending disaster of a trash vortex hurling towards their home. The heaps of trash impact the shores of Taiwan and ultimately transform the lives of the characters as well as the land they live on. I speculate that in the world of The Man with the Compound Eyes, a similar pattern would emerge after the damage and trauma induced by the trash vortex. Haven has already fallen to “touristification” ventures—the development of land, increasing amounts of ecotourism opportunities, and the commodification of indigenous cultures.4 If the novel’s reality is similar to our own, then it is highly possible that this environment would follow a parallel timeline of disaster and rapid development. It is an unfortunate sequence of events, but it is what is occurring in today’s world. Disaster leads to the destruction of homes, ancestral lands, and the cultures that are tied to the environment. Cultural heritage is being used to advance a politico-economic agenda, and the power to control one’s own heritage and narrative is being stripped away from locals through a process of reconstruction, manipulation, and “museification.”5

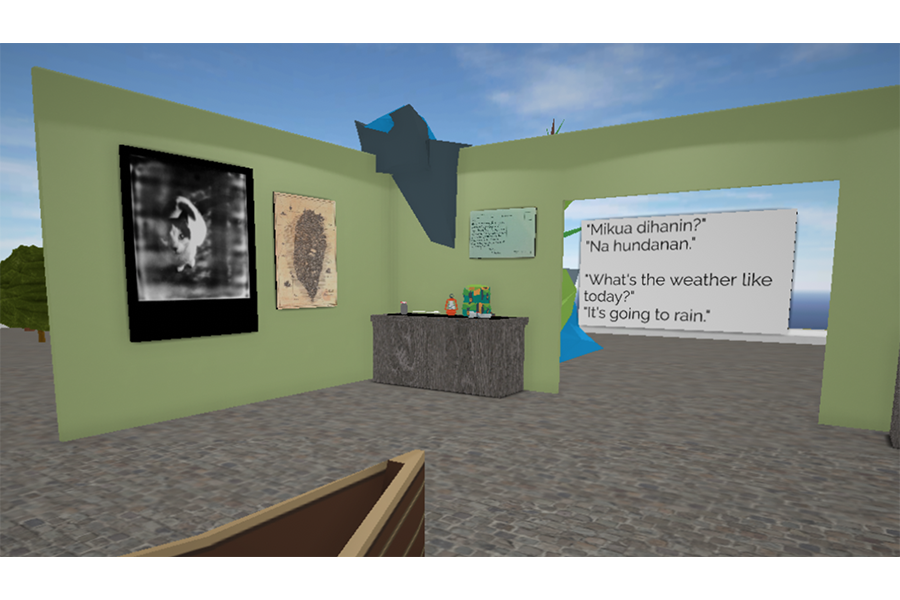

I created a speculative virtual reality museum exhibit that is curated by the characters in the novel themselves. This space is not meant for tourism purposes, but rather personal archival purposes. It is difficult to say what would happen to the people of Haven. They may be displaced as redevelopment occurs, and if that is the case, would they be able to keep the artifacts from their homes? For this reason, this exhibit exists in a digital realm, one where even if the objects were destroyed from disaster, people can still retain the memories through replication. While replication dilutes authenticity, it is an imperfect method for preserving personal objects and practices that may have been destroyed in disaster. However, I aim to raise questions and ways to contemplate how cultural heritage can be preserved as natural and human-made disasters become more prevalent.

This VR museum is by no means an unflawed response to post-disaster cultural heritage preservation. However, it is one opportunity to give the characters in the novel a possibility to retain their own identities and preserve tangible and intangible aspects of their own heritage. Cultural heritage should be considered in post-disaster redevelopment situations, for it protects the social fabric of communities, offering a coping mechanism that yields familiarity.6 Intangible and tangible practices maintain tradition and alleviate the stress of disaster-related trauma, strengthening the resiliency of post-impact environments.7 Current methods of implementing cultural heritage in post-disaster environments are not ideal, and so I find the need for these discussions to occur and for questions to be raised. How can we preserve the social fabric of communities affected by disaster? How can we maintain cultural symbolism in landscapes affected by trauma? How can we ensure that indigenous knowledge is implemented into processes of redevelopment? These are seemingly insurmountable questions, but asking these questions are first steps to identifying a better method of cultural integration in natural landscapes, especially those affected by natural disasters.

- Yujie Zhu, “Heritage Making in Lijiang: Governance, Reconstruction and Local Naxi Life,” World Heritage on the Ground (Berghahn Books, 2016).

- Katina Le Mentec, “The Three Gorges Dam Project—Religious Practices and Heritage Conservation,” China Perspectives, no. 3 (January 2006).

- Romero Renau, Luis. “Touristification, Sharing Economies and the New Geography of Urban Conflicts,” Urban Science 2, no. 104 (2018): 1-17.

- Ming-Yi Wu, The Man with the Compound Eyes, translated by Darryl Strek (Vintage Books, 2015.)

- Paola Demattè, “After the Flood: Cultural Heritage and Cultural Politics in Chongqing Municipality and the Three Gorges Areas, China,” Future Anterior: Journal of Historic Preservation, History, Theory, and Criticism9, no. 1 (2012): 49.

- Jeleński, Tomasz. “Practices of Built Heritage Post-Disaster Reconstruction for Resilient Cities.” Buildings 8, no. 4 (2018): 53.

- Komac and Blaž, “Social Memory and Geographical Memory of Natural Disasters,” Acta Geographica Slovenica, no. 1 (2009): 199-226.