On the weaponization of female sexuality in Cold War advertising.

Bombshells and Booby Traps

The Weaponization of Female Sexuality in Cold War Advertising

How did we go from Rosie the Riveter to June Cleaver? The turbulence of the postwar period and the anxieties sparked by the beginning of the Cold War in America created a specific historical moment that allowed for the weaponization of female sexuality. This weaponization manifested itself in the demonization of the deviant woman, the attempt to contain female sexuality to the domestic, and the emergence of the threat of the female subversive. In particular, this was done through media messaging and popular communications, such as advertisements, where these tropes and narratives of femininity could be coded as part of social reality.1

The roots of this tradition can be traced to World War II, when there was a concerted effort to both mobilize and control female sexuality as part of the war effort.2 The paradox of the “patriotute,” a portmanteau of “patriot” and “prostitute,” exemplifies the contradictions inherent in the “attempt to enlist women’s sexuality in support of the war effort while simultaneously trying to keep women’s sexuality under control.”3 In her book Victory Girls, Khaki-wackies and Patriotutes, Marilyn Hegarty argues that as women were called upon to serve their patriotic duty, their bodies “were drafted in support of the war effort.”4 Pin-up culture presented a close association between sexual allure and patriotism, feeding the “comprehensive notion of patriotic sexuality as a female wartime obligation.”5 However, not all female bodies were equally conscripted in the performance of patriotism. Where mass acceptance of pin-up girls sanctioned the overt sexualization of women as a morale booster for soldiers, the prostitute and victory girl were characterized as diseased and dirty for their “aggressive and undiscriminating” sexuality.6 The pin-up girl is lauded for her performance of patriotism through her sexuality, prostitutes and victory girls are punished for performing theirs, despite the parallels between their behavior.

The tendency to other and demonize the prostitute, in contrast to the pin-up girl, can be explained by distinguishing their respective sexualities. The pin-up girl exhibited a “sexually available form of femininity” that was “rooted in the domestic ideal.”7 Despite her obvious sexuality, her behavior is controlled by the conscription and use of her sexuality for the war effort. This strips her sexuality of individual agenda, and it becomes a non-threatening tool for male use. On the other hand, the sexual availability of the prostitute was very much an exercise of individual agency over her own body. Her unfettered sexuality was dangerous and to be avoided.

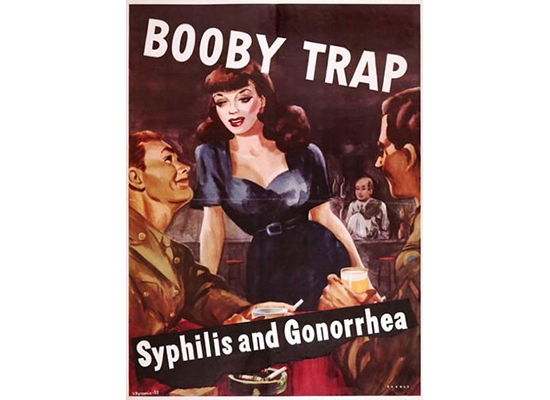

Popular media produced during the war era clearly reflects the cultural stance on prostitution. In this war-era poster, a woman with a small waist, red lips, lush hair, and ample cleavage leans invitingly over a couple of soldiers at a bar. The image suggests that her desirability and beauty are what make her dangerous. The double entendre behind the caption “booby trap” parallels her beauty with a weapon of sabotage, and implies that her allure is merely a decoy for the threat of disease. Her breasts, embodiments of her sexuality, literally connote danger and peril. She is drawn as an active force of temptation, her presence dominating, as the men look upward to her. The eye of the audience is drawn towards her, as well, as she is the center of the poster. Her dominance, unfettered sexuality, and rampant temptation is therefore punished as she becomes a personification of disease. Her sexuality has been coded as a biological weapon.

This weaponization of female sexuality became even more common postwar. Female bodies were commonly codified as and associated with military weaponry and war power. The emergence of the colloquialisms “bombshell” and “knockout” to refer to a sexually attractive woman directly correlated her sexual attractiveness with a military threat. Such terms imbued female sexuality with a threatening character—one that “had to be domesticated or marginalized to protect the culture.”8 As pilots during the war named their bombers after their sweethearts and decorated their planes with erotic portraits, female sexuality became recognized as powerful and dangerous.9 Similarly, the “bikini,” the two-piece swimsuit invented in the 1950s, was named after the 1946 hydrogen bomb test (in which the bomb detonated bore a photo of sex symbol Rita Hayworth) on Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands.10 The demonization of female sexual availability could be perceived as a reflection of Cold War fears of the “femme fatale,” who was a cultural antithesis to the ideal domestic woman, and who epitomized popular fears of the exploitation of female sexuality for the betrayal of national security. The construction and popularization of the character trope through film noirs like Kiss Me Deadly and Vertigo only exacerbated popular perception of independent, sexual women as treacherous.

In light of new anxieties that arose from increasing geopolitical tensions brought on by the emerging Cold War, the uncontained female sexuality became coded as a dangerous national security threat. Ergo, the necessity to contain it became a national security imperative. The justification for this imperative was two pronged: firstly, when contained within the family as a mother and a wife, women played a crucial role in the nuclear family that served as a bastion of security against the instabilities of the Cold War era. Cold War anxieties cast women’s roles within the home as necessary to the stability of society and nation; her domestic duties were now part of civil defense. The whole nuclear family, with the mother at the helm, became the emblem of a psychological fortress, a buffer against both internal and foreign threats. Secondly, sexual deviants were cast as alleged security risks because they could be “easily seduced, blackmailed, or tempted to join subversive organizations.”11 In contrast to the mother, the unwed woman and the sexual deviant became threats to society as individuals who have eschewed their duty to preserve stability.

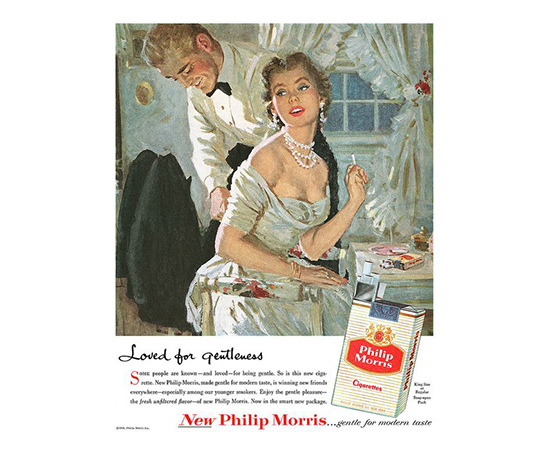

When in the context of a marital relationship or a courtship that might lead to marriage, a woman’s sexuality and feminine allure was accepted or even encouraged. Elaine Tyler May argues that women in the 1950s practiced “sexual brinkmanship,” in which young women set out to “snare a husband by engaging in everything up to, but not including, sexual intercourse.”12 The use of sexuality and feminine allure in advertisements to sell products “reflected an American preoccupation with sexual satisfaction,” but one that was acceptable only within the confines of marriage.13 In the Phillip Morris advertisement below, the body language and composure of the woman pictured parallels that of the prostitute in the “Booby trap!” poster. Her cleavage is similarly bared, her eyes are hooded in invitation, and she leans forward invitingly. Like the prostitute, she is alluring. However, unlike the prostitute, her sexuality is mitigated by the presence of the man in the advertisement, who stands behind her in an intimate position. Presumably her husband, he legitimizes her sexuality and allure, allowing advertisers to position her as an acceptable image of desirability. The caption, “loved for gentleness,” could indicate both the man and the cigarette—as a woman who has managed to contain her sexuality appropriately, she deserves gentleness in both her cigarettes and her husband, and she is an ideal fit for emulation.

The imperative of containment further manifested in physical and psychological ways. The popularization of Christian Dior’s “New Look” echoed a postwar shift in attitudes to an increased focus on domesticity and traditional gender roles in the home. The exaggerated hourglass figure and structured silhouette emphasized the feminine parts of the body, like the hips and the bust. This contrasted starkly with the austere look of wartime, when the rationing of fabric and prioritization of function over form necessitated simple, utilitarian fashions. In order to fit the silhouette of the New Look, women’s bodies had to be controlled using constricting rubberized undergarments “in the Victorian tradition.”14 Even as the sexualized parts of the female body were emphasized in order to highlight her femininity, the body under the clothes was being restrained, contained, and controlled.

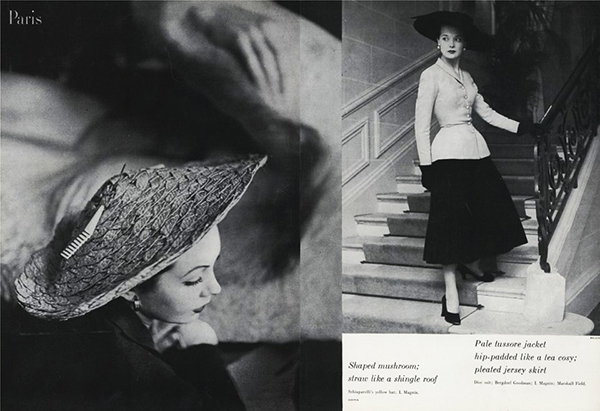

In this Dior spread from the April 1947 issue of Vogue, the model’s impossibly cinched waist and padded hips are far removed from reality, but her painful emulation of the feminine hourglass ideal suggests that her appeal lies in the distortion of her body for the male gaze. Her sexuality is not only being contained by her clothes and her appeal to a masculine viewer, but also by the references in the advertisement to domestic terminology. Her skirt is “hip-padded like a tea cosy” and her straw hat literally positions a “shingle roof” over her head. The use of domestic terminology as adjectives in the advertisement collapses the woman herself with the domestic by constituting the woman as parts of her domicile. It also suggests that the female target audience would be most likely to identify with and respond to a call to the domestic. In its totality, the advertisement mirrors the recognition of the danger of female sexuality by calling for its containment on female bodies and in households.

Similarly, the emergence of the conical bra epitomized the double-edged sword of conservative domestic ideology by simultaneously containing female sexuality and weaponizing it. Even as her sexuality is confined and controlled, it was made to be menacing and hostile. The cups of the conical bra, shaped into aggressive points, resembled the nose cones of rockets and fighter planes. Through clothing, Americans turned breasts into warheads.15 Some advertisements appeared to claim that the use of the conical bra could liberate women. The Maidenform advertisement campaign “I Dreamed I Was . . .” features a series of young women performing male-only tasks, such as bullfighting and winning an election, while wearing an exposed bra. The advertisements ironically suggest that a woman’s sexuality is restricting, and that by containing her breasts she will gain access to domains previously restricted to her. Once her sexuality was contained, she could dream of leaving the home. The campaign also suggests that women could be empowered through consumption: The mere purchase of a bra would allow her to straddle the realms of the political and the domestic. However, the contrast of women being portrayed in public in their private undergarments suggests that their actions were in the realm of fantasy.

Furthermore, as mothers and housewives, the idealized domestic woman of the Cold War era could participate in patriotism and cooperation by participating in consumption, which had become framed as a weapon against communism. In the Westington advertisement below, the housewife is used as a yardstick by which her kitchen appliances are fitted. Seemingly innocent, the advertisement reveals underlying assumptions about the woman’s place in the kitchen. By using her almost as a unit of measurement, the advertisement assumes that only she will be using the kitchen, thereby asserting that her domestic responsibilities in the kitchen are hers alone and can be fitted for her personal use, just like clothes or shoes. The advertisers behind the image also assume that this subtext would appeal to their buying audience, a demographic of women who would be attracted to the constructed solution of easier access in the kitchen.

Through their roles as domestic household consumers, women could participate in and further a patriotic and nationalist project of American dominance and influence. The notion of the domestic as a domain of conflict surfaced during the 1959 “Kitchen Debate” between then-President Richard Nixon and Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev. Nixon argued that American superiority and Cold War triumph would be accomplished not by military supremacy but through the secure, abundant life that free enterprise could offer, especially now that modern appliances lightened the workload of women so they could be more easily fulfilled as housewives. Nixon located the essence of American freedom in the “model home” of the male breadwinner and female homemaker, through which a secure, abundant family life could be achieved through modern suburbia and consumerism. Consumption of household objects would therefore not be an end in itself, but “the means for achieving individuality, leisure and upward mobility.”16 The domicile had become another Cold War battleground, where women were the soldiers.

The codification of female sexuality as dangerous in the 1950s can be seen as part of a larger sociopolitical project, a return to traditional gender roles and domestic ideals as a defense against Communism. The unique conditions that produced Cold War anxieties such as subversion and anti-Communism led to the disruption of the social and moral fabric of postwar society. This included the problems of the changing gender dynamics and a return to normal society from the gendered and polarised wartime conceptions of the “military front” versus the “home front,” In turn, these tensions precipitated the weaponization of female sexuality through popular culture. In particular, the growing importance of the Cold War in political ideology of 1950s allowed for the discourses of gender, sexuality, and individual liberties to be mapped onto concerns about national security that justified the militarism and consumerism of the time. The advent of the golden age of advertising smoothed the way for this shift by allowing advertisers to interpret and reinforce cultural ways of seeing through a pattern of images and text in advertising discourse that weaponized female sexuality.

- Williamson, Judith. Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising. London: Boyars, 1978. 18-19. Print.

- Hegarty, Marilyn E. Victory Girls, Khaki-wackies, and Patriotutes: The Regulation of Female Sexuality during World War II. New York: New York UP, 2008. 156. Print.

- Ibid. 158

- Hegarty, Marilyn E. Victory Girls, Khaki-wackies, and Patriotutes: The Regulation of Female Sexuality during World War II. New York: New York UP, 2008. 156. Print.

- Ibid, 112

- Rowley, Marie. “Constructions of Femininity in Postwar American Historiography” Psi Sigma Siren 2nd ser. 7.2 (2012): 15. Web.

- Ibid. 14.

- mith, Geoffrey. “National Security and Personal Isolation: Sex, Gender, and Disease in the Cold-War United States.” The International History Review 14.2 (1992): 307-37. Web.

- May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in Cold War Era. New York: Basic, 1988. 110. Print.

- Vandermeade, Samantha L. “Fort Lipstick and the Making of June Cleaver: Gender Roles in American Propaganda and Advertising, 1941-1961.” Madison Historical Review 12.3 (2015). History Commons. Web.

- May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in Cold War Era. New York: Basic, 1988. 95. Print.

- Vandermeade, Samantha L. “Fort Lipstick and the Making of June Cleaver: Gender Roles in American Propaganda and Advertising, 1941-1961.” Madison Historical Review 12.3 (2015). History Commons. Web.

- Ibid.

- Coleman, Barbara J. “Maidenform(ed): Images of American Women in the 1950s.” Gender Journal 21 (1995). Proquest. Web.

- Caldwell, Doreen. And All Was Revealed: Ladies’ Underwear, 1907-1980. New York, NY: St. Martin’s, 1981. 81. Print.

- May, Elaine Tyler. Homeward Bound: American Families in Cold War Era. New York: Basic, 1988. 17-18. Print.