The development of modern data-collection technology enabled scientists, politicians, and historians alike to employ quantitative methods in historical analyses—and allowed them to purposely shape the Cold War narrative.

Cold War Counting

The Role of Data in Forming Narratives

Statistics can contribute to a pathos appeal as much as any other rhetorical tool, adding intensity and drama. Purely quantitative facts can garner an emotional response that an audience would otherwise lack. To say that data provide a completely objective view of any topic would be naive, especially when applied to understanding history. Choosing which statistics to report inevitably results in some sort of bias, as do the language and context in which they’re presented. This bias can hold immense power when attempting to generate a particular response or opinion. Since the introduction of complex data tools during the early Cold War years, statistics have been connected to audience response. The development of modern data-collection technology enabled scientists, politicians, and historians alike to employ quantitative methods in historical analyses—and allowed them to purposely shape the Cold War narrative. Just as leaders during the Cold War period used data to justify the intense fear of communism, historians now incorporate statistics to better convince their audience of their interpretation of events.

The United States and the Soviet Union became increasingly dependent on new data collection technologies as the Cold War steadily progressed. With the emerging focus on social studies, the technologies helped American officials garner an understanding of public response to diplomatic strategies. From 1957 to 1958, the International Geophysical Year (IGY)collected data from sixty-seven countries intended to share between all participants. The program collected information on various topics, but “all of IGY’s thirteen disciplines had direct military implications.”1 Innovative for its time, the countries reported their information on physical microfilm and produced booklets to turn in. For the first time in history, the United States relied on complex data collection systems to make crucial decisions. Additionally, the American Research and Development Corporation (RAND), established in 1948, promoted the incorporation of formulaic strategy in the political world. A product of RAND, the Delphi Method created “a way of quantifying, analyzing, and understanding potential threats by this Communist ‘menace.’”2 With this, came the increased popularity of “futurists,” scientists who used these methods to make predictive claims about the future. These modern methods allowed the American government to justify their oftentimes extreme responses to communism, what they viewed as an incredible threat to democracy. No doubt, there likely existed some mathematical truth to their predictions and analyses, but from an epistemological standpoint, we should remain skeptical about the legitimacy of these invented models. This technology, in the context of a newfound appreciation for the social sciences, permitted politicians and scientists to unite and begin to form a preferred narrative of the Cold War before it had even occurred. Decades later, authors would cite the same data contrived during this time, consequently repeating the historical story the Cold War politicians had begun to shape. Because internal support was crucial to the United States’ success, these methods proved extremely valuable in understanding the minds of the American people.

The way in which new technologies could generate and manipulate data explains the superpowers’ craze over access to data as well as the consequential danger. The technology enabled the United States to amplify the threat of communism based on pure anticipations of what would possibly have become true. Forerunners of the practice, such as John Tukey, claimed in the early sixties that unlike mathematical statistics, which were heavily applied during World War II, data analysis “would be dedicated as much to discovery as to confirmation.”3 The distinction explains the originality of the predictive models and pattern recognition tools and the enthusiasm that surrounded them. The futurist practice “rationalized, modeled, and quantified complex issues and developments of economic, social, and scientific nature.”4 How much could be trusted when conclusions put purely abstract issues into such quantified terms? The trustworthiness of what the data said was not of great importance; instead, politicians cared about justifying their military decisions and obtaining support from the general population. Because of the power of statistics to sway the public, the Cold War introduced data collection as an advantage in the brewing Soviet-American rivalry.5. Evidently, statistical knowledge was of great value to the countries involved in the Cold War. Not only did it provide insight into otherwise incomprehensible trends, but it also functioned as a mechanism for shaping the timeline of the Cold War in the most convenient manner. The introduction of data collection technology and the fundamental analyses done during this time would have lasting impacts on understanding the Cold War’s narrative in the future, including the very basis that it is examined through a social science lens.

John Lewis Gaddis is widely recognized as a Cold War history connoisseur and worked until recently as a military and naval history professor at Yale University. His most famous book, The Cold War: A New History, published in 2005, serves as the most popular Cold War introductory book in the United States. That being said, the account receives criticism for its blatantly good-versus-evil narrative between the United States and the Soviet Union, respectively. For example, well-known book review blog Rhapsody in Books concludes, “The Cold War: A New History provides an excellent example of the ideological biases of a historian creating a skewed misrepresentation of the facts about an era in order to conform with biased perceptions.” In Gaddis’s version of the Cold War, the United States emerged as an underdog to triumphantly defeat the evil spread of communism conducted by the Soviet Union. It is a narrative that favors America in every way, making the country the hero anyone would root for in an action film.

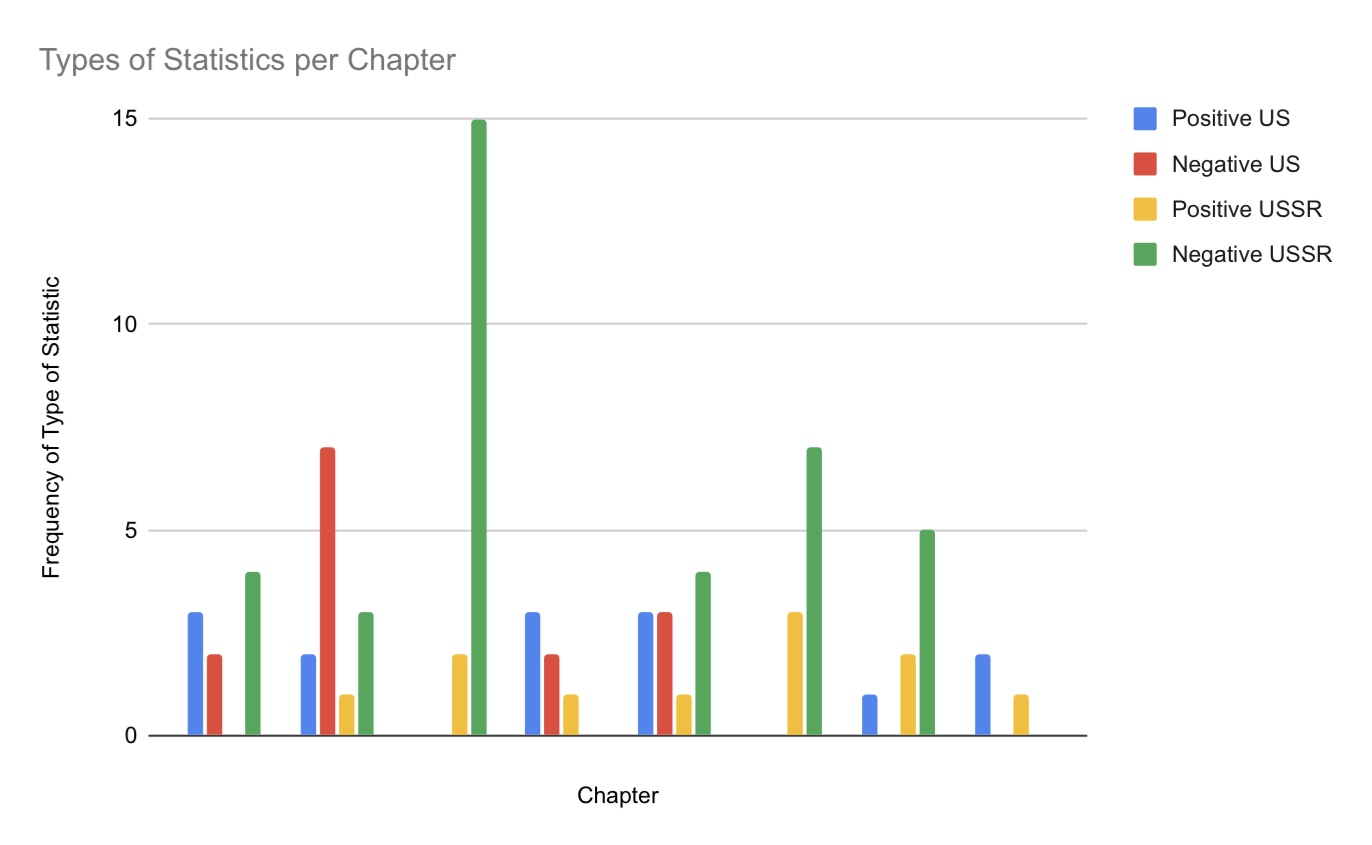

After seeing these critiques of Gaddis’s work, I wanted to explore any apparent trend in the statistics he chose to include in the book and how he presented them that would aid in forming a good-versus-evil narrative. Upon evaluating every statistic included in the book, I identified which statistics belonged to any of the four following categories: positive American, negative American, positive Soviet, and negative Soviet. Statistics belonging to the positive categories may include any examples demonstrating the country’s strength, success, or ethical nature. One example of a positive American statistic is “The United States at the end of 1950 had 369 operational atomic bombs, all of them easily deliverable on Korean battlefields or on Chinese supply lines from bases in Japan and Okinawa.”6 A negative statistic could be any that depicts the country as weak, unsuccessful, or unethical. For example, a negative Soviet statistic is, “The Stalinist dictatorship had either ended or wrecked the lives of between 10 and 11 million Soviet citizens—all for the purpose of maintaining itself in power.”7 The following graph depicts the frequencies of each category of statistics for each chapter of the book.

The graph illustrates that the frequency of negative Soviet statistics, depicted in green, was by far the highest and consistent throughout the book. The uptick in negative American statistics in chapter 2 strongly supports the narrative that many readers accuse Gaddis of fabricating or more mildly augmenting. It demonstrates his argument that the United States entered the Cold War disadvantaged against the Soviet superpower. One such statistics, “McNamara’s own planners estimated that 10 million Americans would be killed in such a conflict [with the Soviet Union], even if only military forces and facilities, not civilians, were targeted.”8 Gaddis establishes in the beginning stages of the narrative that the United States felt threatened due to their lack of military preparation and the number of countries that the Soviet Union could easily influence into adopting a communist economy. In any traditional story, the underdog always receives the support and admiration of the audience, and further, the underdog’s accomplishments seem far more impressive when no one expected successful outcomes. Gaddis attempts to situate the United States in this role so that to celebrate its handling of the Cold War may be appropriate. Likewise, encouraging statistics for the United States are relatively frequent throughout the chapters, reinforcing the country’s stable strength throughout the conflict it endured.

Some of the data Gaddis uses to establish the Soviet Union, and other proponents of communism, as the evil power should seem suspicious to anyone with any statistics education. I do not suggest that Gaddis completely fabricated these facts, but it seems plausible that they lack definite proof of legitimacy. Gaddis claims that “Not only did Soviet troops expropriate property and extract reparations on an indiscriminate scale, but they also indulged in mass rape—some 2 million German women suffered this fate between 1945 and 1947.”9 Worthy of consideration is whether Gaddis would have claimed the same fact had Americans, for instance, been the perpetrator. From a technical standpoint, it is difficult even to imagine where to begin to collect this data with a crime that victims hardly report, especially when perpetrated by people of power. Gaddis cites the book The Russians in Germany by Norman Naimark as his source. Gaddis and Naimark alike are strategic in possibly inflating the severity of crimes when it taints the Soviet image. Similarly, Gaddis also includes, “[Communism], when put into practice, may well have brought about the premature deaths, during the 20th century, of almost 100 million people.”10 Including the word “may” hardly makes the usage of this statistic any more responsible. To suggest that one hundred million people died due to communism is a bold statement that dramatically enhances the Cold War narrative in which the U.S. is virtuous. Throughout the book, Gaddis undermines the responsibility of the United States for the deaths of citizens in third-world countries, meanwhile probably exaggerating the degree of harm that communism caused.

Although Gaddis never claims to provide a completely objective analysis of the Cold War, Paul Senese supposedly offers just that in his book Steps to War: An Empirical Study. He performs a statistical examination of the Cold War period to determine why this tension is exceptionally different from other wars in that it never turned “hot.” Senese identifies the statistically proven causes of war, meaning that if conditions meet these qualifications, the probability of a violent encounter increases. The first of these is determining how significant the stakes of the conflict are and to what degree rivalry can escalate them as they are abstracted. In the case of the Cold War, the stakes are “West Berlin, standing for West Germany, and then West Germany standing for Western Europe, and the latter standing for the entire Free World.” 11 Senese also argues that the arms race and the intense rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union should have led to a violent outbreak. With an otherwise statistically proven theory that applies to all other areas of modern history, the Cold War reigns as the most prominent exception. This fact demonstrates the complexity of the Cold War that we cannot apply otherwise standardized reasonings of international conflict. One could argue that the data analysis of the Cold War did not provide any practical understanding of the events. Still, it reveals why the topic receives much debate and confusion. The empirical study of war shows why the abstract nature of the Cold War facilitates the difficulty in identifying its cause, its period, and whether or not it even deserves the label of a war.

A prominent yet essential feature to consider of Senese’s empirical analysis is that he evaluates the historical period as a time of peace compared to the treacherous violence during World War II. Instead of recognizing the violence that did occur due to ideological tensions, Senese treats the outcomes of the Cold War as an exception to the more dramatic rates and manners of death in other wars. He even quotes a 1987 book by John Lewis Gaddis calling the Cold War period a “long peace.”If the author employs Gaddis’s interpretation of the Cold War, this should mean that statistical analysis supports Gaddis’s narrative. One main similarity between the two analyses demonstrates why they could believe this period to be a “long peace,” even when Gaddis references 3,063,337 individual deaths due to Cold War conflicts: Senese and Gaddis treat the Cold War as a conflict solely between the United States and the Soviet Union. Violence directly between the two countries accounts for an extremely small portion of the total deaths related to the Cold War. One can judge their perception either as a more conservative, superficial understanding of the Cold War or, perhaps, as neglecting the damaging effects on third world countries that the superpowers coerced into participating in the Soviet-American conflict.

Historians today employ the same statistics collected during the Cold War by then-new technology and practices, such as the Delphi Method and IGY, allowing them to influence their interpretation of the events and, consequently, the audience to which they share their understanding. Worth consideration is that the same people who used this technology are the people who invented it. The United States created the Delphi Method reacting to newfound appreciation for the social sciences to truly understand response to military circumstances. Officials used the data to justify the political moves they decided to take and shape the American public’s opinions on the matter. Similarly, modern interpretations of the Cold War, such as John Lewis Gaddis’s, employ statistics to form their analysis into the favored account. For many Americans, this story is one in which the United States took part in an essential battle against the evils of the communistic Soviet Union while maintaining military ethics throughout and emerging victorious despite the odds. Paul Senese’s empirical study of the Cold War demonstrates how even the most objective analyses could result in a somewhat biased interpretation:The history professor considers the Cold War period a time of constant peace and analyzes it as such compared to other wars. Examining the history of technological development during the Cold War and modern analyses demonstrate how people of power can produce and reference statistics to influence an audience. This remains true even while we tend to deem employing data the most objective way of understanding history. Furthermore, we see how data has its limits when used to evaluate the social sciences, so abstract and complicated, to provide an unbiased examination.

- Elena Aranova, “Geophysical Datascapes of the Cold War: Politics and Practices of the World Data Centers in the 1950s and 1960s,” Osiris 32, no. 1 (2017): 307–327..

- Mark Solovey and Hamilton Cravens, Cold War Social Science: Knowledge Production, Liberal Democracy, and Human Nature (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 45.

- Matthew L. Jones, “How We Became Instrumentalists (Again),” Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences 48, no. 5 (2018), 675.

- Solovey, Cold War Social Science, 46.

- Aranova, “Geophysical Datascapes of the Cold War,”

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (Penguin Books, 2007), 84.

- Gaddis, The Cold War, 136.

- Gaddis, The Cold War, 111.

- Gaddis, The Cold War, 40.

- Gaddis, The Cold War, 159.

- Paul Domenic Senese, and John A. Vasquez, Steps to War: An Empirical Study (Princeton University Press, 2008), 35.