“Does it stand that photography is a legitimate form of visual art?” An exploration of the photograph and its varied applications.

Redefining the Lens

An Exploration of the Applications of Photography

What is photography? If you break down the word “photography” into its etymological origins, you find that it translates into “drawing with light.” Indeed, the process of capturing a photograph involves recording the amount of light in a given space, either with an image sensor or light-sensitive material. This information is subsequently processed into a photograph through either digital or chemical methods. Photography has utilitarian uses as well as artistic ones; the ability to instantly capture a picture has vastly changed many aspects of society, including scientific research, medicine, historical documentation, and mass communication. However, photography is also used for the artistic pursuit of self-expression. The invention of the camera has revolutionized the visual arts. Whether it is Dorothea Lange’s portraits of workers during the Great Depression and her subsequent influence on documentary photography, or Helmut Newton’s provocative fashion photography that was widely featured in Vogue and other publications, or Cindy Sherman’s self-portraiture that sought to question the representation of women in society, the contributions of photographers have had a significant and largely positive impact on contemporary culture. Although photography has become common as both an artistic and utilitarian practice, it still has yet to be universally accepted as a form of art. By examining the arguments both for and against photography’s status as a fine art, I will show that, despite the skepticism surrounding its legitimacy, photography is indeed a form of art. Whether the circumstances behind a photo are elaborate and predetermined or captured by happenstance, art photography depicts an artistic intent or vision, regardless of the subject. Whether it is used for art or utility, at its core, photography is intended to communicate.

In order to determine whether or not photography is an art, we must set some guiding principles about what defines art. In its simplest and broadest definition, art is form and content. Form refers to the appearance of a work, which consists of the media used to create the piece, the techniques utilized in such creation, and the way in which the elements of design interact throughout the piece. Content is the conceptual element of the piece; it is the presentation of an idea—the intellectual conversation an artist has with a viewer through the work. 1 Art is an inherently human effort that combines creativity and skill. In the case of visual art, such works usually involve the creation of an image or object with a range of tools. Art often intends to represent some aspect of reality or truth, as well as characterize thoughts and emotions. It can also seek to remember the past by representing historical events, interpret the mythology at the foundation of many cultures, and celebrate the richness of these cultures. Ultimately, creating art is a human experience that may not always be intentional in the final outcome, but is intentional in the conception and the desire to communicate.

With these definitions in consideration, does it stand that photography is a legitimate form of visual art? The answer is a resounding yes: photography is indeed an art. It is a human effort that combines form and content so that an idea may be shared with a viewer in a visually engaging way. Though there are many fundamental differences between the various artistic media, photography is just as much of a visual art as painting. The photographer utilizes the camera in the way that the painter utilizes the brush in order to create a composition. However, despite this general understanding of photography, critics of the practice disagree. Much of the disagreement centers on the fact that photography involves the use of a camera, a piece of machinery that allegedly removes the inherently human aspect of artistic expression from photography. According to this thinking, the photo is not a product of skill and creativity; the machine that is the camera has taken the work out of capturing the image by automating the process. In his essay, “Why Photography Does Not Represent Artistically,” Roger Scruton argues that a photograph cannot be a representation in the same way a painting is; rather, it is a presentation of how an object looked at a certain time. Scruton’s “ideal photograph” is an image that is incapable of representing anything unreal, as it stands in direct relation to the object that was photographed.2 He argues that a photograph of a draped nude called Venus, for example, is not a representation of the Greek goddess; rather, it is a photo of a representation of a Greek goddess. The photograph cannot represent—instead, it points to a moment in which representation was happening.

Scruton’s stance is one that is completely removed from the purpose of representational photography and in fact attempts to refute the validity of artistic intent. Take Jeff Wall’s photo After Invisible Man for example: Wall’s photo is considered a constructed image because the set was constructed solely for the photo. Scruton would dismiss the photo itself and argue that the representation of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man is in the construction of the set and not in the photo. However, the set only exists for the purpose of being captured and preserved in a photograph; upon finishing the photo shoot, the set would likely be taken down and no trace of it would continue to exist except for the photo. The setup itself is not a representational performance; all of its elements were placed to capture a moment from Invisible Man as an image, and this fact makes the image a representation.

It is often argued that a camera, unlike a paintbrush, is a piece of machinery that can be preprogrammed and adjusted. Ted Cohen addresses the criticisms of the mechanical aspect of photography in his essay, “What’s Special About Photography?” when he writes that much of the thought regarding the legitimacy of photography “often seems to amount to an obsession with the fact of the camera, with the fact that it is a machine” 3 For this reason, photography is considered a practice that does not require skill, as anyone is able to pick up a camera and take a photo. Cohen states, “this automatism is cited as an inherently unartistic or uncreative core in photography.” The mechanical aspect of photography supposedly removes the artist from their art, makes a photograph impersonal to the photographer, and ultimately detracts from the overall artistic merit of the practice. Furthermore, in “Photography and Representation,” Scruton states that the photographer lacks total control over his work, and refers to photography as “the causal process of which the photographer is a victim.”4 He sees the events behind a photograph as an instance that happened to be captured by a camera. While it is true that the machine does the actual physical act of capturing of an image, the camera is just a machine without its photographer, and a scene is just an instance in time without the photographer to capture it. The photographer is responsible for seeing and appreciating such a moment, whether that moment is beautiful, thought provoking, or allows for an idea to be communicated. The artist has the ability to make choices that change the way a photo will ultimately appear, whether that is in lighting, composition, or other formal elements, and it is these decisions that go into taking a photo that make it a human experience.

Another of the major arguments against photography is rooted in its accessibility as a practice. Skeptics believe that taking a photo is easy, simply because it has become an automated process. 37% of users on debate.org, an online debate platform, argue that photography is not a form of art primarily because they perceive that there is no skill involved in pointing a camera and pressing a button.5 They believe that while it takes years of instruction and practice to hone the skills of a painter or sculptor, anyone with access to a camera can take a nice photo. The machinery of the camera takes out all of the effort that goes into creating a piece of art; taking a photo is a mindless action, but a painting or sculpture is a product of skill and dedication to the craft. This mindset is problematic as it assumes that the significance of a piece of art is determined by how much effort was put into the physical creation of it rather than a judgment of its form and content. Furthermore, it also assumes that every photo will be good simply because it was taken. Many critics of photography do not separate casual picture taking from art photography. The advances of modern technology have made taking photos easily accessible to the masses, and to some, that anyone with a smartphone can snap an aesthetically pleasing picture is a degradation to the value of photography. DSLR cameras are readily available on the market, and camera technology continues to make advances that allow for higher quality and more accessible photos to be taken. However, the artistic value of a photograph is not dependent on the fact that one is capable of taking a photo. In “What’s Special About Photography?” Cohen recognizes that “It is undeniable that photography is automatically in possession of a capacity for a kind of gross, generic representation”6, and it is this kind of representation that is cause for photography to be challenged by those who do not separate generic pictures from art. However, the fundamental difference between a photographer and one who takes photos is artistic intent and message. In Edward Mendes blog post, “Artist or Photographer, which one are you?” he defines a clear distinction between an artist and a photographer. Mendes writes:

A photographer is quite literally a person who takes photographs, either as a hobby or a profession . . . on the other hand an artist is defined as a person whose creative work shows sensitivity and imagination . . . so a photographer is simply someone who uses a camera while an artist is someone that uses skill and imagination in the creation of a work of art.7

His distinction between casual photographers and art photographers is crucial to the understanding of the art. While anyone who has the means can purchase a high quality digital camera, the ownership of such a tool is meaningless in regards to being an art photographer. A nice picture is not the same thing as a good photograph, and whereas a nice picture is visually accessible, a good photograph is cerebrally stimulating. When observing a photograph for the purpose of understanding it as a piece of art, one must consider the elements of the photograph that contribute to the message or intent of the photographer. This message is key in drawing the line between an ordinary picture and a photograph. Mendes argues that utilizing the creative process in photography is an extremely conscious process that extends beyond pointing a camera and pressing the shutter button; it is a personal and decisive process in which the artist is fully aware of the choices he or she is making. In order to understand an image beyond its form, these choices must be considered for their content. On the other hand, a casual picture is generally taken because the photographer wanted to capture the way a thing looked in a specific moment—an intention that aligns with Scruton’s beliefs that photography is purely an image of a representation. When such a distinction between art photography and casual picture taking is made, the practice can be fully appreciated as a form of art separate from its utilitarian purposes.

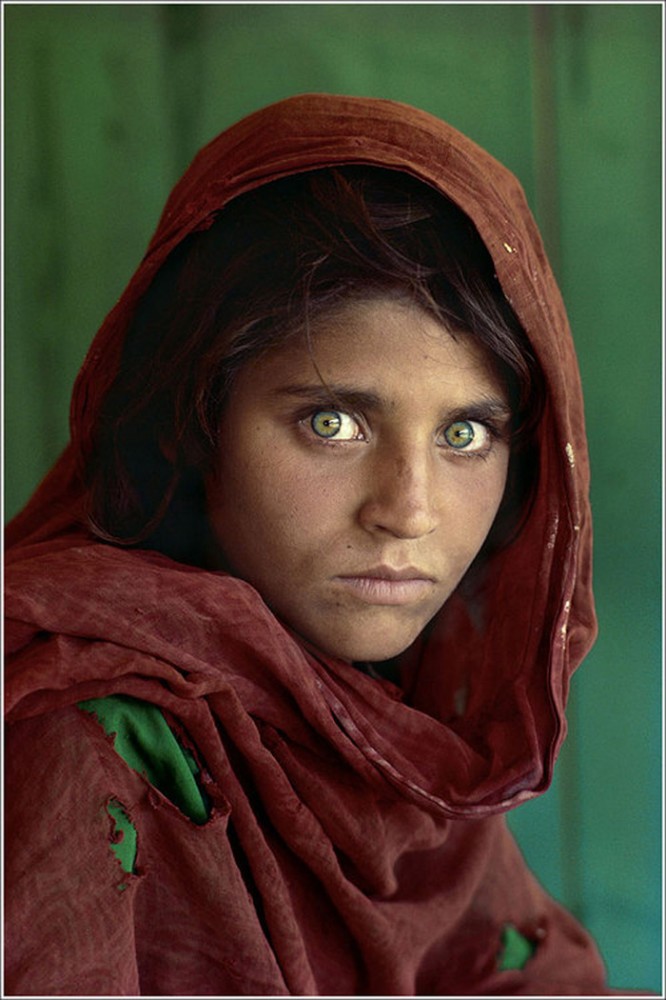

Photography, like any other art, needs to be examined with the proper lens in order to be fully understood and appreciated. In an article that explicates the aspects of a photo that need to be reviewed to determine its standing as a work of fine art, A. Cemal Ekin identifies the five elements of a photo that need to be examined for such a claim to fine art to be legitimate: message, intention, choice, technique, and print. Ekin believes that the first and most crucial aspect of a photo is the message. He writes, “I do not mean a social commentary, something extraordinarily profound, but a meaning encoded into the photograph is essential.”8 For example, Steve McCurry’s Afghan Girl, a photo considered the most recognized photograph from National Geographic, would simply be a portrait of a young girl if it were not for the message inherent to the photo. McCurry, who is known for his focus on “the human consequences of war, not only showing what war impresses on the landscape, but rather, on the human face,” captured this portrait of a young refugee during the Soviet war in Afghanistan to show the condition of the refugee condition.9 Ekin also stresses the importance of intention, which goes hand in hand with his argument about choice; he states that the “execution of the photograph should come across with reasonable force.” He believes the photographer’s choices should be evident in the image. McCurry’s intent and choices are clearly seen in his portrait; the way in which the red of the girl’s shawl frames her face and so starkly contrasts with her striking gaze demonstrates Ekin’s argument. It is these choices “that separates accidental snap shots from artistic expressions.”10 His argument moves into the technical aspect of photography, not only when he talks about technique, specifically the technical execution of tools in the process, but also when he addresses print—a personal choice that is not requisite for all photography. Ekin’s blog post is primarily his own approach for the consideration of photography as fine art through an examination of form and content. It is this kind of understanding of any work of art that is necessary for a greater appreciation of it.

We come back to the question: is photography an art? At times and among certain circles, the question seems almost ludicrous—of course photography is an art. However, the answer depends on the nature of the question. Photography needs to be separated into two spheres: photos taken with artistic intent, and photos taken for utility, whether that utility is for medical purposes or sentimental ones. Photography has uses that extend outside the use of artistic expression, and it is these uses that prevent photography from being universally accepted as a form of art without a question. In order for a photograph, or any composition, to be considered art, one must discover whether there is artistic intent in the piece. A painted piece of furniture would not be considered a work of art simply because it was painted, and the same type of distinction applies to photographs. Photography, like all art, is an artist’s means of sharing an idea with the world. However, it can also be a non-artistic way for families to look into their past, for manufacturers to produce better commodities, and for academic texts to become enriched with visual aids. Today, photography stands at the forefront of methods in which to capture an image and, as technology expands, photography will only become more advanced. With the change that will inevitably come from an ever-growing pool of accessible technology, art will be subject to change just as it was when the camera was first invented.

- Munro, Thomas. “Relationship between Form and Content.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica, n.d. Web. 12 May 2014. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/7484/aesthetics/59174/Relationship-between-form-and-content/>.

- Scruton, Roger. “Why Photography Does Not Represent Artistically.” Aesthetics in Context, CD-ROM

- Cohen, Ted. “What’s Special About Photography,” The Monist, Volume 71, Issue 2, 1988. 82.

- Scruton, Roger. “Why Photography Does Not Represent Artistically.” Aesthetics in Context CD-ROM

- “Is Photography Art?” Debate.org, n.d. Web. 15 May 2014. <http://www.debate.org/opinions/is-photography-art>.

- Cohen, Ted. “What’s Special About Photography,” The Monist, Volume 71, Issue 2, 1988. 82.

- Mendes, Edward. “Artist or Photographer, Which One Are You?” Edward Mendes Landscape and Nature Photography RSS.N.p., 13 Mar. 2011. Web. 6 May 2014. <http://www.edwardmendesphotography.com/blog/?p=216#.U1l_cuZdXns>.

- Ekin, A. Cemal. “Fine Art Photography.” Kept Light Photography. N.p., 29 Mar. 2007. Web. 19 Apr. 2014. <http://www.keptlight.com/fine-art-photography/>.

- Photographer Steve McCurry Biography on National Geographic. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 May 2014.

- Ekin, A. Cemal. “Fine Art Photography.” Kept Light Photography. N.p., 29 Mar. 2007. Web. 19 Apr. 2014. <http://www.keptlight.com/fine-art-photography/>.