The main problems with the increase in thrifting today stem from corporate greed and gentrifiers reselling stock, or just ignoring neighborhood customs and not supporting local businesses.

The Gentrification of Thrift Stores and its Ecological Effects

Just off the New York Brooklyn Bound L train, J train, or M train you can find a neighborhood peppered with graffiti art and coffee shops. A place where you can tell each building has a story, and although it may appear desolate on a Tuesday, it will be lively all twenty four hours of the day on a Saturday. My father Walter Bobadilla, who moved to Bushwick from Honduras in 1978, recalls the storefronts being covered in plywood following a blackout in the summer of 1977 when local businesses were looted.1 The neighborhood, once taken over by low-budget Latino immigrants, is now split between these old-time residents and chain businesses like Starbucks, along with their loyal customers.

In 2018, the annual number of new certificates of occupancy in Bushwick more than tripled. In 2000, the median annual income of the neighborhood was less than $20,000. Twenty years later, the median income is approximately $57,460, although the groups making this amount or greater are younger and newer residents, ranging from under twenty-five to forty-four years old.2 Smelly, a longtime resident of Bushwick, and the current manager of Select Vintage says that much of the change in the neighborhood is positive, new people moving in and creating a nightlife scene means that the streets are safe at night.3 However, he also noted that the neighborhood has much less of a community feel, and he no longer has relationships with his neighbors. He also noticed that the prices at local stores, specifically delis, are being raised and new businesses coming in are creating much more of an urban feel than most Brooklyn neighborhoods have. The shift of the economy happening in Bushwick echoes the larger implications of gentrification happening all over New York City, specifically boroughs bordering Manhattan. Bushwick in particular is seen as an up and coming neighborhood that is gaining popularity through its presence of thrift stores. The streets that were always sprinkled with affordable local secondhand shopping outlets are now beoming attractions with vintage stores that appeal to new residents coming in.4

Even outside of Bushwick, thrift stores are commonly found all throughout New York City, but secondhand clothing was not always so easily accessible. In the nineteenth century, people simply did not get rid of clothes. The clothes became a commodity, rather than the industry. Clothing was all handmade, and many households knew how to sew and would fix buttons, apply patches, and more to expand the life cycle of their clothing.5 When the Industrial Revolution hit, people were still not throwing away their newly store bought clothes; they found ways to donate excess clothing items to charity organizations helping immigrant families. Charity shops and an increase in clothing production in the 1920s meant that upper-class women in particular could indulge in more shopping without feeling bad about getting rid of clothing through donations. During World War I, sales were down, so both Salvation Army and Goodwill began creating catchy antique window displays and opening stores on busier “shopping streets,” instead of low-income areas.6

Even with these efforts, it was mostly the post-war fashion industry that ultimately made second-hand shopping more desirable for higher-income families.7 Magazines and fashion brands—now pushing fashion into seasonal styles and driving consumerism habits up—set the distinction between cheap thrifting and fancy vintage investments that set apart the upper-class from the middle-class. During the social movements of the 1960s, the popularity of counter-culture meant that hippies and bohemians wanted to downplay their status through clothing, and began thrifting as well.8 This anti-consumerist, pro-thrifting outlook of fashion movements and aesthetics continued into the 1990s. In the 2000s, retail stores caught onto this phenomenon of recurring styles being thrifted, so companies like Urban Outfitters began to lean into more distressed yet urban styles, winning back the upper-class streetwear audience.9

In recent years, the resurgence of secondhand clothing began again just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, when the climate movement began to gain traction with protests and strikes happening globally. The fashion industry is the second most polluting industry and is notorious for abusing its laborers in developing countries, so the de-stigmatization of second-hand shopping, or thrifting, for all socioeconomic statuses began. In 2022, 74 percent of thrift shoppers said it is more socially acceptable than it was five years ago.10 One chain business that was initially founded in Bushwick and has since become a thrifting empire is L Train Vintage. This curated thrift store has been duplicated and expanded throughout the city, and this development echoes a bigger phenomenon that is taking place in this neighborhood currently.

Within the thrifting community, there are two main types of thrift stores, curated and donation-based stores, and two separate kinds of thrift shoppers, the thrift-seekers and the “creativists.”11 Thrift-seekers go to thrift stores in search for bargains, while creativists have less financial limitations and go to thrift stores in search of unique pieces. 12Examining the types of thrift stores in Bushwick, it is clear that the donated store aligns more closely with the thrift-seekers. The products in these stores are all donated items, and the stores overall generally have a cheaper price point. They also do not turn down many donations, if any at all, so they tend to carry more fast-fashion and cheaply made items. The thrift-seekers, although they may not be interested in cheaply made items, are interested in finding bargains for well-known brands. They also, on average, have fewer years of education and lower incomes, although they tend to have the same number of children and fall in the same age ranges as their creativist counterparts.13

Curated thrift stores are composed of high-quality vintage and secondhand clothing that is purchased from outside merchants, or donation-based thrift stores, where all these pieces fit a particular theme, aesthetic, or trend in order to attract customers to spend more money on their items.14 In general, curated thrift stores like L Train Vintage are much more responsible for the rise in thrift store prices, since they take discounted pieces from donated stores, raise the prices, and then attract wealthier clientele.15 Curated stores pride themself on unique one-of-a-kind vintage pieces and a cohesive shopping experience, so it can be assumed that the creativist shoppers are their target market. Creativists are a group of wealthy people that see shopping as an ethical practice, or a counterculture to typical department store clothing consumption.16 This group understands the harm to both humanity and the environment that clothing production causes, and they value the artistic expression that clothing can bring, especially when the items cannot be easily found again.17 They do not have financial limits and are less likely to come into a thrift store with particular needs in mind than the thrift-seekers.18

It is also important to note that this group of creativists is fueled by the era of overconsumption that we are currently in.19 They are still products of capitalism and are often purchasing more than they need.Although the creativists have good intentions and are conscious of the harm they cause on some level, both the shoppers and the stores they frequent can have negative effects on lower-priced stores and on their clientele. Creativists are more aware of the social implications of their shopping habits than the economic factors, when in reality, their gentrification of second-hand shopping centers may ultimately change the function of such spaces. It is possible that, because higher income people are beginning to value thrifting through the creativist’s lens, overtime the thrift-seekers may be “priced out.”20 This concern is minimal, because although stores like L-train have seen a significant price increase, Goodwill has stayed mostly consistent, with their price increases being a reflection of the economy rather than the customer base changing.21

Considering the variety of customers and the recent rise of thrift shopping, the Bushwick neighborhood has a pretty clear distinction between these realms. The stores almost serve as an unspoken border between long-time local residents and newer residents who are just beginning their thrifting journeys. In recent years, the only new thrift stores being created are curated stores of varying price ranges, which tend to host an audience of people traveling across the L train line to visit, and new local residents. There is a diverse form in which these stores can be found, from L Train Urban Jungle, the largest thrift store in New York, to a truck parked outside of the Morgan Avenue subway station that is operated by two local men hoping to supply affordable ($10-$20) garments to people in need.

One of the men who operate the Morgan Avenue vintage store truck informed me that the clothing not sold in the truck within a few months is quickly sold on eBay in a matter of days.22 Smelly from Select Vintage stated that because he works for a curated store that follows a theme, none of the clothes there have a time limit or are thrown away after a certain period, although they do have an e-commerce platform too so their items have the opportunity to reach a larger customer pool.23 Although thrift stores operating on donations in Bushwick do provide a more equitable distribution of clothing, since they are not up-charging prices on clothing they purchased elsewhere, a downside is their waste management or lack thereof. Due to the overproduction of clothing in America, the shopping addictions many citizens have, and the new normalization of buying second-hand clothing, donations now come in extreme surpluses and many stores that accept donations struggle to hold on to all of these items.24 Many of the workers at these Bushwick locations did not speak English, so I did not get to speak with anybody working in these stores directly and cannot confirm that they get rid of old stock or send them to places like Ghana as textile waste, where they often end up in oceans and landfills.25 However, this is what many donation-based stores like Goodwill are known to do, and I am fairly confident that these stores, such as Le Point Value Thrift, or Domsey Express in Bushwick do not have e-commerce platforms to expand their customer base and give their items a better chance of being sold.

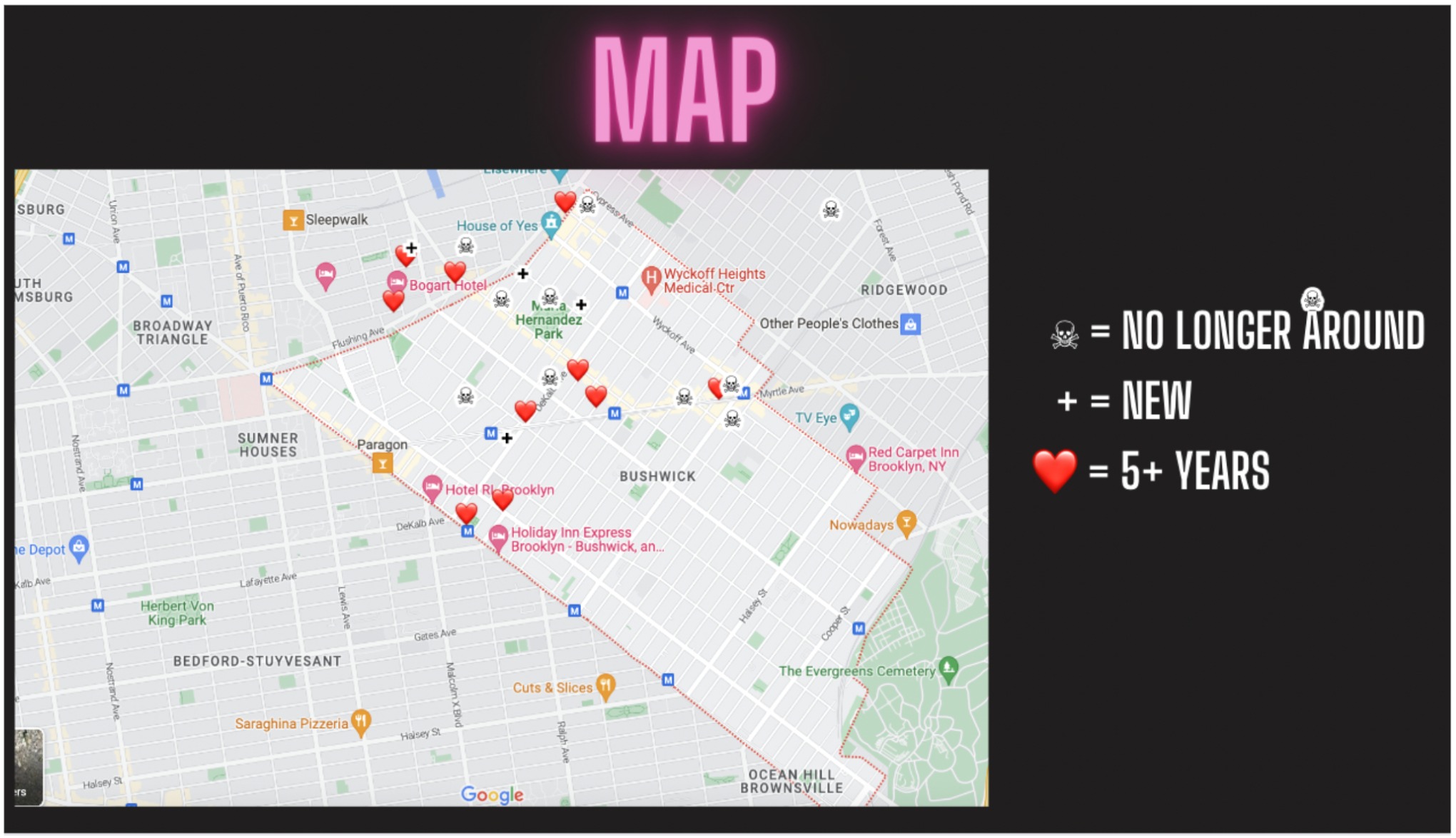

The relationship between thrift stores and residents in this neighborhood is much more complicated than it appears to be. Although donation-based stores produce more waste, they are creating a buffer and a chance for renewal between an individual’s clothing waste and landfills and still hold many environmental benefits. They are also providing clothing for low-income families. The gentrification of Bushwick in general shows a lack of participation from new residents in local businesses, including donation-based thrift stores. The new thrifting customers that fit into a creativist frame of mind can overtime raise the average price point of thrift stores, and may eventually out-price the thrift-seekers abilities to thrift. A Niche survey of the local residents said that 13 percent of them wanted to tell new residents to support local business, and another 13 percent wanted new residents to only move in if they’re broke, both implying disparities in the type of establishments flourishing in the neighborhood.26 My own observations of this neighborhood did show much more traffic in newer and curated stores, as well as a significant amount of local thrift stores that have completely disappeared in the neighborhood recently. This means that rather than creativists raising prices, they may be driving out local thrift stores altogether, as is evident in the map showing how many stores have recently closed. It also means that these places are producing more waste because many of their items are not being sold, potential customers, especially ones that are willing to spend more are less inclined to shop at them.

With all of these details about the current thrifting scene in Bushwick, and the other rapid changes the neighborhood is undergoing, it is still important to recognize that thrifting is not a form of shopping that should be reserved for any one class of people. Assuming that only lower-income families can shop secondhand is classist. Thrifting combats the overproduction of clothing and participating in it considering the amount of clothing being donated each day is not harmful. Yet, taking pieces from affordable thrift stores to sell them at a higher price for wealthier people is unethical, and overconsumption is currently plaguing our country, fueling companies to produce clothing at an unsustainable rate. Many people excuse thrifting as a way to still indulge in their overconsumption habits. Large corporations have changed us to view our clothing at a lower value, and find pieces interchangeable with the season. It is important that we learn to take care of and value our clothes and the business providing them again. The main problems with the increase in thrifting today stem from corporate greed and gentrifiers reselling stock, or just ignoring neighborhood customs and not supporting local businesses. But there are still many affordable thrifting options in Bushwick, and it is important that we keep these businesses going, while also keeping in mind issues of waste management, and overconsumption.

- Walter Bobadilla, interview, conducted by Olivia Bobadilla, April 1, 2023.

- “Bushwick Demographics and Statistics,” Niche,

www.niche.com/places-to-live/n/bushwick-new-york-city-ny/residents/ - Smelly, interview, conducted by Olivia Bobadilla, April 2, 2023.

- Smelly, interview.

- Hazel Cills,“The Complicated Reality of Thrift Store ‘Gentrification,’” Jezebel, April 30, 2021.

https://jezebel.com/the-complicated-reality-of-thrift-store-gentrification-1846113458. - Cills, “The Complicated Reality,” https://jezebel.com/the-complicated-reality-of-thrift-store-gentrification-1846113458.

- Cills, “The Complicated Reality,” https://jezebel.com/the-complicated-reality-of-thrift-store-gentrification-1846113458.

- Cills, “The Complicated Reality,” https://jezebel.com/the-complicated-reality-of-thrift-store-gentrification-1846113458.

- Cills, “The Complicated Reality,” https://jezebel.com/the-complicated-reality-of-thrift-store-gentrification-1846113458.

- Natasha Cornelissen, “Curated Thrift Stores Flourish in an Era of Overconsumption,” Keke Magazine, Jan. 24, 2023,

www.kekemagazine.com/2023/01/24/curated-thrift-stores-flourish-in-an-era-of-overcons

mption/. - S. Steward, “What Does That Shirt Mean to You? Thrift-Store Consumption as Cultural Capital,” Journal of Consumer Culture 20, no. 4 (Nov. 2020): 457-477, EBSCOhost,

https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540517745707. - Steward, “What Does That Shirt Mean to You?”

- Steward, “What Does That Shirt Mean to You?”

- Cornelissen, “Curated thrift stores,” https://www.kekemagazine.com/curated-thrift-stores-flourish-in-an-era-of-overconsumption/.

- Cornelissen, “Curated thrift stores,” https://www.kekemagazine.com/curated-thrift-stores-flourish-in-an-era-of-overconsumption/.

- Steward, “What Does That Shirt Mean to You?”

- Steward, “What Does That Shirt Mean to You?”

- Steward, “What Does That Shirt Mean to You?”

- Rabiah Kahol, “Is the Thrift Culture Trend Better Than Fast Fashion?” Talk D’Hart It to Me, n.d.,

https://www.talkdhartitome.com/post/is-the-thrift-culture-trend-better-than-fast-fashion. - Morf Morford, “Who Killed the Thrift Store?” Tacoma Daily Index, Jan. 24, 2023, EBSCOhost,

search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edsnbk&AN=18F3FEB18CDC7718&s

ite=eds-live. - Cills, “The Complicated Reality,” https://jezebel.com/the-complicated-reality-of-thrift-store-gentrification-1846113458.

- Unknown vintage vendor, interview, conducted by Olivia Bobadilla, April 2, 2023.

- Smelly, interview.

- Cornelissen, “Curated thrift stores,” https://www.kekemagazine.com/curated-thrift-stores-flourish-in-an-era-of-overconsumption/.

- Priya Ayushee, “Impact of Second-Hand Clothing Waste in Ghana,” International Journal of Law Management & Humanities 5, no. 2 (2022): 1.

- “Bushwick Demographics and Statistics,” Niche,

www.niche.com/places-to-live/n/bushwick-new-york-city-ny/residents/.