Ecological art and memorial design in the Anthropocene

Urban Eco-Memorial

Facing Ecological Grief

Humanity faces unprecedented ecological challenges at a planetary scale. The climate crisis and the sixth mass extinction remind us that diversity of life on earth is under siege by the twin environmental crises of the twenty-first century. The world has already lost two-thirds of its wildlife in fifty years—a haunting reminder that we are living in dark ecological times. In the face of this incalculable loss, there is an increasing interest in the psychological burden of environmental destruction. This burden will by no means be restricted to intellectual and activist circles. Coping with ecological grief—or climate grief—may emerge as a pressing social concern this century. It is unclear to what extent this shared anxiety and despair will drive social change, but it serves as an example of the challenges posed to contemporary ecological awareness. The ongoing debates over the post-1950 acceleration of human impacts have contributed much to our understanding of social and ecological change in the twenty-first century. As we wake up to the troubling reality of living in a high-carbon future, the transition to the Anthropocene encourages us to reflect on what has already been lost. How can we process ecological grief in the age of climate change and mass extinction? Are we even equipped to deal with the shock and anxiety that is generated when we recognize the scope of environmental destruction?

There is an existing, interdisciplinary body of literature on this subject, with psychologists and environmental researchers examining the psychological burden of ecological loss. The research surrounding ecological grief and anxiety is still in its nascent stages, but the increasing scholarly and public interest in this topic is arguably a promising sign. This emerging field of inquiry underscores the need to develop effective coping strategies in the face of ecological loss. As we learn to live with the troubling reality of environmental destruction and ecocide, we cannot escape the existential questions surrounding grief and memory in the Anthropocene.

My proposed land-art project for the Urban Eco-Memorial draws inspiration from themes associated with contemporary environmental philosophy, as well as the challenges presented to ecological awareness in the twenty-first century. The principal goal is to rethink memorial design, with the ambition of improving ecological awareness and helping city-dwellers process ecological grief.

Memorializing Nonhuman Nature

How should we remember what is already lost? It is important to recognize that a diversity of thought exists surrounding the memorialization of nonhuman nature.1 Environmentalists, historians, and even landscape artists have approached this question in a variety of ways. One might turn to the Grande Galerie de l’Évolution in Paris, where the Room of Endangered and Extinct Species contains specimens that are often the last remaining examples of their species. While the museum itself reminds countless visitors of the diversity of nonhuman life, here we see the reality of environmental destruction laid bare. From hunting to habitat loss, this room reminds us that human activity threatens that very diversity.2But how can the memory of ecological loss be expanded outside of natural history museums? How can we move from these educational exhibitions into the communities where ecological grief is felt most profoundly?

Here we might consider the work of landscape artist Alan Sonfist, whose project, Time Landscape, brought the concept of a natural memorial into the streets of Greenwich Village. Located just south of Washington Square Park, Time Landscape stands as a testament to the precolonial Manhattan landscape. Created between 1965 to 1978, this rectangular plot of land on West Houston represents the three stages of forest growth. In his essay on “Natural Phenomena as Public Monuments,” Sonfist stated that his intention was to create a natural memorial—a lone forest in the midst of a megacity that turns our attention to the past.3 In the aftermath of the planting process, the intrusion of postcolonial plants has generated new questions about our conceptions of nature. Sonfist’s work serves as a landscape portrait of the past, but the introduction of these new species forces us to reconsider the existence of ecological spaces in a century defined by human activity. Not to mention the waste and pollution that community members routinely remove from the boundaries of this micro-haven in the Village. Our impact on the nonhuman world can now be seen in the spaces we build as well as in the spaces we go to separate ourselves from the built environment. Even the practice of land art is no longer immune from the changes taking place at a planetary scale. There is certainly a need for more careful consideration of our approaches to the memorialization of nonhuman nature in the Anthropocene. As the landscape art in our cities is reshaped by human activity, we may consider new artistic approaches to promote ecological awareness. But how exactly do these reflections fit into the landscape of contemporary environmental philosophy?

Dark Ecology in Practice

Timothy Morton has been described as a philosopher for the Anthropocene. In recent years, their writing has generated significant discussion and debate, particularly around humanity’s severe impact on the biosphere. Morton, who uses they/them pronouns, has become a prominent figure in contemporary environmental thought. As an author and academic, their work often deals with the destruction of the nonhuman world, the state of planetary crisis, and the uncertain ecological future we face. Morton’s penchant for neologisms has certainly distinguished their writings in environmental discourses. “Hyperobjects,” “the ecological thought,” “the mesh”—these terms have been adopted by various humanities scholars and environmentalists. Morton’s linguistic approach reminds us not to be shy in the search for new tools, whether conceptual or practical, that may help us address the existential environmental challenges of the present. This approach to philosophy is often framed using the umbrella term Dark Ecology, also the title of their 2016 book. In this wide-reaching text, Morton offers a series of reflections on agricultural society, climate change, and ecological awareness. By drawing from a diverse set of academic disciplines, Morton outlines the philosophical, ethical, and humanistic dimensions of our relationship to the nonhuman world.4

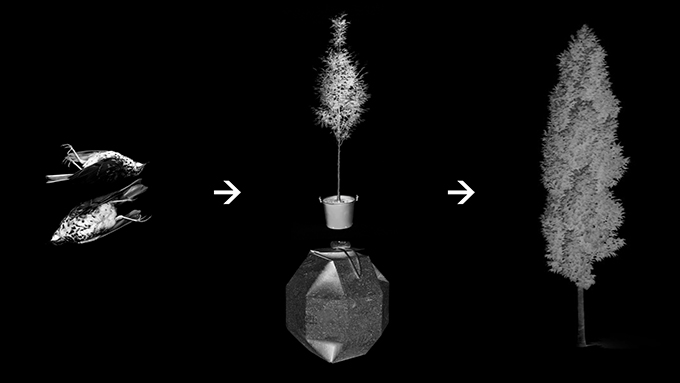

Morton is certainly not the only writer associated with Dark Ecology; Graham Norton and Paul Kingsnorth have both played a major roles in the emerging discourse. There are significant disagreements among these figures when it comes to the conclusions they draw about twenty-first-century environmentalism. Nevertheless, their work has centered the dark ecological discourse on the need to face environmental destruction and cope with ecological grief. Morton’s ecocritical writing has, at times, been described as inaccessible to the average reader who is unfamiliar with their previous work. There are certainly substantive criticisms that stem from creating a closed dialogue—one, that is harder for non-academic readers to join at a time when public engagement is more important than ever. Nevertheless, Morton’s work has been essential in shaping current debates within environmental philosophy and ethics. Their writing has certainly pushed environmentalists, academics, and even artists to place ecological awareness at the center of their intellectual and artistic work. While each of the figures mentioned above have made important contributions to environmental thought, it was the writings of Timothy Morton that served as inspiration for this project’s approach to memorial sculpture and land art. Some of the central motifs in Morton’s book, Dark Ecology: For a Future of Coexistence, are presented right from the start on its cover art: Flowers are shown to be growing out of the remains of dead wildlife. It was this depiction of death, decay, and rebirth that motivated the application of Morton’s ideas to ecological art and the memorialization of nonhuman nature.

Symbols of Solidarity

One of the first questions that emerged from this project was how it builds upon and also differs from existing memorials, aside from its emphasis on eco-awareness. How does it draw from the history of memorial design, while simultaneously challenging our ideas about the spaces we build for the memory of others? In search of answers, one might turn to the wealth of information that exists surrounding the history of memorial architecture.

The Hiroshima Peace Memorial, also referred to as the Genbaku Dome, stands as one of the most moving memorials that one is likely to find. In the aftermath of the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, the Hiroshima Prefectural Industrial Promotion Hall was one of the few structures that remained. The hall itself was reduced to ruins, but the Genbaku Dome, or Atomic Bomb Dome, survived the blast and now serves as a powerful tribute to the victims of the bombing, who number over 140,000. The structure has been preserved in its condition following the bombing of August 6, and in 1952, an accompanying cenotaph was designed by the Japanese architect Kenzō Tange. This saddle-shaped monument contains the names of the Hiroshima bombing victims, with the Atomic Bomb Dome framed in the background.

While the aesthetic dimensions of Tange’s memorial encourage us to reflect on the history of memorial design, one cannot forget that its true meaning derives from the desire to create a lasting symbol of peace following the use of the most destructive weaponry in human history. Countless visitors to Hiroshima Memorial Park have visited this moving tribute to the victims of the first nuclear attack. For decades it has reminded us of the horrors of modern warfare, and inspired generations of activists advocating for nuclear disarmament. As we face unpreceded ecological threats to human and nonhuman life in the twenty-first century, we may benefit from drawing inspiration from the form and function of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial.

Arborsculpture for the Anthropocene

The Urban Eco-Memorial incorporates the themes of Timothy Morton’s Dark Ecology to propose a new approach to tree sculpture—a dark ecological recreation of the Atomic Bomb Dome.

In the Urban Eco-Memorial, the decay of urban wildlife feeds new life in the form of tree sculpture—one which will take the shape of the Atomic Bomb Dome. To begin, the bodies of urban wildlife and tree saplings are placed in biodegradable cork burial containers, along with nutrient-rich soil. These cork containers are arranged in a circle and buried with two meters of spacing between saplings. The bodies and cork containers ultimately decompose, and over the course of a decade, the branches emerge from the burial container to create an interconnected dome structure. These branches are woven together throughout the growth process to create an ecological memorial in the form of arborsculpture.

This proposed land-art project relies primarily on the use of tree shaping, a process in which branches are woven together to create living architecture. Arborists and land artists often use the process of grafting to create connective plant tissue. Figures such as British land artist David Nash have pushed the limits of tree sculpture by using the grafting process to create radical new designs that challenge our understanding of ecological architecture. In order to guide the growth process of the Urban Eco-Memorial, an internal cage is used to provide structural support. The branches that emerge from the burial containers wrap around this wire structure, with the end result resembling an ecological recreation of Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome. This living memorial to urban wildlife will transform in the years following the planting of saplings, perhaps becoming unrecognizable as the dome is enveloped in plant life. Although this structure will also change in appearance throughout the seasons, it will always serve as tribute to the loss of urban wildlife.

This approach to arborsculpture and ecological awareness is decidedly in line with the themes associated with the dark ecologists. Here, the loss of nonhuman life is not a peripheral consideration but, rather, exists within the roots of the structure. It encourages reflection on the pursuit of ecological peace, as well as solidarity with nonhuman city-dwellers. As a melancholy eco-sculpture for the Anthropocene, this structure could function as a space for ecological remembrance. It may serve as a physical reminder of our collective need to rethink the connection to nonhuman nature in dark ecological times. A structure that not only encourages consideration of ecological loss and grief, but also challenges our conceptions of peace in a century defined by ecological loss.

Designing Haunted Architecture

In a 2016 interview with Archinect, Morton stated that “Buildings are haunted, not just by their past, but also by their future.”5 They go on to effectively make the case that our approaches to design are in no way separate from our relationship to the environment. Whether we look at the ecological harm that is built into our architecture today, or the impact of the built environment on future generations of human and nonhuman life, it becomes clear that design and eco-awareness are one and the same. These “overlapping temporal scales” encourage us to think critically about the future of ecological architectural practices.6 How might green design play a role in driving the social and psychological change necessary to face ecological loss in the Anthropocene? The proposal for the Urban Eco-Memorial aims to answer that question by expanding our understanding of the memorial to include spaces for ecological remembrance.

Some might be skeptical of social change taking place in response to ecological loss, given the history of inaction on environmental crises. However, the possibility of an eco-dystopian future is alerting many to the environmental challenges of the twenty-first century. The slow and continuous violence directed at earth’s biosphere has already generated a range of social responses, and it remains to be seen what the cultures of ecological awareness, resilience, and mourning will look like in the years to come. In the face of this uncertainty, we must place a greater emphasis on the pursuit of social and ecological peace, as we develop new approaches to remember that which is already lost.

- Margo DeMello, editor, Mourning Animals: Rituals and Practices Surrounding Animal Death. MSU Press, 2016.

- “Grande Galerie De L’Évolution (Gallery of Evolution),” Muséum National D’Histoire Naturelle.

- Alan Sonfist, “Natural Phenomena as Public Monuments,” A Companion to Public Art (2016): 34-35.

- Timothy Morton, Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence (Columbia University Press, 2016).

- Nicholas Korody,“Timothy Morton on Haunted Architecture, Dark Ecology, and Other Objects,” Archinect.

- Korody,“Timothy Morton on Haunted Architecture, Dark Ecology, and Other Objects.”