Is fashion designed to restrict and subordinate women, or can it be a source of self-identification and liberation?

The Female Body, Covered

What does it mean to be a woman in society as it functions today? That is a question which elicits no simple answer. Where I often land is that being a woman means seeking to prove my worth to the world—seeking to prove that I am more than my body, that I am more than the length of my skirt or the cut of my shirt. Novelist and critic Chimamanda Adichie asserts that women learn to self-police from an early age.

We teach girls shame. ‘Close your legs. Cover yourself.’ We make them feel as though being born female they’re already guilty of something. And so, girls grow up to be women who cannot say they have desire. They grow up to be women who silence themselves. They grow up to be women who cannot say what they truly think. And they grow up—and this is the worst thing we do to girls—they grow up to be women who have turned pretense into an art form.1

Women so often live by standards of behavior that dictate how to dress, how to act, how to speak—women essentially live by standards that dictate how to live. “We teach girls shame.” We teach women to hide their bodies, to be afraid of their own sexuality, to be desired by men. In this paper, I seek to understand this complex relationship between women and the world, as manifested through our struggle with the fashion system.

Throughout history and across most cultures, women have been subjugated to men. Thorstein Veblen argues that women were the first form of property—beginning with “the seizure of female captives” to serve as trophies.2 This gave way to the ownership—in the form, for example, of marriages that established men as heads of the household. I would argue that the concept of women as prizes and property has continued to thread its way through history and persists still today. Veblen, writing at the end of the nineteenth century, makes a similar argument: that women are displays of a family’s wealth and status (or, more specifically, of a man’s wealth and status). The woman of the leisure class as described by Veblen seems to be just a continuation of the reduction of women to trophies during what he calls the “predatory stage” of social history; only, in Veblen’s leisure class, women are trophies that specifically display a man’s financial success. Veblen attributes the historically restrictive nature of women’s dress to woman’s position as a vehicle for the display of wealth. In support, he notes that male fashion tends to adapt to the needs of men (both physically and societally) much more than women’s fashion to the needs of women. There is no functional reason behind the corset, the full skirt, or the high heel—all major trends in women’s dress at different points in history; rather, each makes movement more difficult for the wearer. Only women who could afford to be physically restricted were able to wear any of these ridiculous inventions—women who had to work or perform any sort of manual labor needed the mobility that such articles prevented. In order to display the wealth of her husband, the wife would lace up her corset, add layers to her already full skirt, and add inches to the heel of her shoe. And the man? He wore his dress pants and slightly stiff shirt. The significance of these trends goes beyond an expression of wealth. Corsets not only imposed specific ideals of feminine beauty upon women but also regulated their behavior and “signifi[ed] women’s subordinate status.”3

Similarly, high heels (nearly impossible to walk in) were adopted by women because they lessened the appearance of shoe size and “accentuat[ed] the curve of the back”: women wore high heels to be more attractive to men (more attractive, however, on male terms).4 Ironically, men often complain about the clumsiness of a woman’s gait in heels, yet continue to swoon at the shoes’ effect on the allure of her legs. Elizabeth Wilson points out the harsh reality of this absurd fashion: The high heel makes it nearly impossible for a woman to run away from a pursuer, increasing the likelihood of sexual harassment.5 Not only do women look “more attractive” in heels, but they also look (and are) more vulnerable.

But why do women take part in this oppressive system of fashion that is seemingly designed to restrict and subordinate them? Georg Simmel argues that women have often participated in fashion because they were cut off from most other spheres of life (namely public life). Here I will add that throughout history, women have believed in and accepted their supposed inferiority and staked their worth on their ability to attract men, which would explain why women would partake in a system that does not seem to consider their comfort, but rather places emphasis on socially accepted ideals of femininity. However, returning to Simmel’s argument, he states that fashion “both gives expression to the impulse towards equalization and individualization as well as to the allure of imitation and conspicuousness.”6 Because of their weak status within society for much of history (and, I would argue, still today), women have felt that they had to conform to female norms in order to be accepted. Simmel argues that those in the weaker position wish to remain inconspicuous and find comfort in being part of a group.7 Women, because they have been relegated to a weaker position throughout much of history, have coveted a sense of belonging. Simmel also argues that it is the duality of fashion that specifically appeals to women—that is, that they can create “an individual ornamentation of the personality” while also partaking in the “sphere of general imitation.”8 Rebecca Arnold makes a similar claim: “women in particular,” she writes, “were drawn further into fashion’s realm to seek fulfillment through its fantasy images, to construct a self based upon desires rather than needs.”9 Women who felt constantly inferior to men in every sphere of life could find an outlet in fashion, which focused on creating a female identity. This identity, however, is generally one created by and for men, but in the name of women.

Various concepts of femininity seem always to have been at work within fashion—a concept, however, that changes throughout time and exists in many different forms. For much of history, before women’s place under men began to be challenged, femininity suggested softness, submissiveness, silence, delicacy, innocence: all traits that women felt they had to embody, and to dress to embody whether or not they actually felt connection to any of the qualities. Femininity is most conspicuously represented in fashionable dress, as is best seen in the restrictive fashions mentioned previously that keep women physically dependent on men, thus characterizing the woman as weak and delicate, in need of someone at once to coddle and to control her. However, these ideals, since the rise of feminism and increasing gender equality, have been at war with newly emerging concepts of what it is to be a woman. As women moved into the public sphere and were more visible, they began to disregard “the Edwardian notion of femininity as a delicate flower to be cosseted and protected from the harsh realities of modern life.”10 Although women were advancing, in encroaching on formerly male dominated territory, backlash inevitably occurred. Men were threatened by this increased power. This threat is suggested in the New Look designed by Dior in 1947, which, according to Allen, reached back to a romanticized past “symbolized by objectified femininity.”11 Women during the postwar period were in constant conflict between being perceived as representing “virginal femininity” and “eroticized femininity.”12

As women’s involvement in the world increased, naturally, feminism did too. Within feminism, there appear differing opinions on how women should interact with cultural systems, and with the fashion system in particular. There is the argument against woman’s participation in fashion: the “whole-hearted condemnation of every aspect of culture that reproduced sexist ideas and images of women and femininity.” Proponents of this school of thought see fashion as an oppressive system, and for women to adhere to fashion would only continue this oppression.13 Then there is the other argument—that of the pro-fashion feminists who find it “elitist to criticize any popular pastime which the majority of women [enjoy].”14 These feminists see fashion as a valuable outlet for women’s self-expression and, accordingly, as one viable medium of their emancipation. In Elizabeth Wilson’s book, she described this debate within feminism that essentially questions the compatibility of a woman’s choice to partake in a clearly sexist industry and her ability to find personal liberation in dressing: “Does [fashion] muffle the self, or create it?”15 If feminism preaches equality, does this not mean that it preaches the ability to choose? And if feminism is centered on the freedom to choose, should not a woman be able to choose how she dresses without being labeled by men (or by other women) a slut, a prude, or even an anti-feminist? This question is still not resolved. Rebecca Arnold describes the ability of fashion to liberate the woman in that she gains strength by finding “her own sexuality and allure through notions of beauty and power, sexuality, and independence.”16 These notions of beauty, however, lie far from the natural body. Women who have sought liberation in fashion have seemed constantly to be straddling the thin line between sexy and whorish—but why do women feel the need to be sexy? Is it for the male gaze or for their own liberation? Arnold suggests that women are able to find liberation in the fashion system by reclaiming their own identities and refusing to let them be defined by men.

Fashion’s feminist potential is replete with broader questions about gender. It has long been established that gender is a binary construction; however, more recently, this by now conventional wisdom, too, has been challenged. Sex, which refers to one’s biology, differs from gender, which refers to the cultural construct of the male-female binary. As Judith Butler writes, “gender is the cultural meaning that the sexed body assumes,” but it has no real basis in biology other than that, historically, humans have labeled one type of genitalia to be male and the other to be female.17 This idea of binary gender, to me, does not cause problems until one considers the gender norms associated with each—norms that are not reflections of the population, but rather patriarchal and often sexist ideas of how the genders should behave. In popular dress, gender is divided along clear and strict lines. As I have already mentioned, the way in which a woman presents herself through fashion is much more controversial than a man’s choice of dress: Women are held to strict standards of being just modest enough to be sexually attractive nevertheless. Even more controversial is the moment that one attempts to cross the lines between the strict (yet unspoken) gender normative dress codes of our culture. Butler, for instance, discusses the idea of a false or prohibited identity: “those in which gender does not follow from sex and those in which the practices of desire do not ‘follow’ from either sex or gender.”18 Those who do not fit within their imposed gender or sexuality struggle to find their place in a society that rejects any identity that does not follow the norms established generations ago. This idea of false identity is clearly displayed in fashion. Both men and women are expected to adhere to certain rules pertaining to fashion: women wear skirts, men wear pants; women wear fitted shirts, men were loose shirts, and so on. If you do not dress according to your gender norms, you must be “wrong.”

In the case of women, femininity has virtually without exception been an issue in one’s dress. Women are expected to wear clothes that accent whatever idea of femininity is in style at the time. Interestingly, the restrictions of male clothing seem to consist only in the injunction that men should not wear female clothing, but within culturally accepted male clothing there is significant freedom. That the rules of dress are more prescriptive for women aligns with Butler’s observation that, somehow, we associate the “mind with masculinity and body with femininity.”19 It appears that female identity resides solely on the surface of the body, represented so clearly in women’s close relationship with fashion and what Caroline Evans sees as the inability of our society to separate the female from her body.20 The idea of femininity is parodied in cross-dressing, or drag. Drag creates a dramatized femininity that loosens the constriction of the inner psyche and its relationship to the outside. At first glance, drag seems to degrade women and perpetuate gender roles within fashion; however, Judith Butler points out that it goes beyond the surface. Drag is not a parody of the original (whether femininity or masculinity) but is a parody of the idea of the original. It brings to our attention “three contingent dimensions of significant corporeality: anatomical sex, gender identity, and gender performance.”21 Drag—with its overtly sexualized depictions of women—calls attention to the absurdity of female gender norms and socially acceptable femininity. Therefore, drag does not enforce gender normative dressing, but rather calls into question the very truth of gender itself, i.e., the idea that there can be a “right” and a “wrong” way of “doing” one’s gender.

I will now shift to more recent considerations of female sexuality in fashion, primarily focusing on the male reaction to increasing female power. In the 1920s, as women (and society at large) seemed to embrace the natural body with the flapper dress and the fight against the corset, women were quickly gaining power (in the workforce and with the power to vote in many countries across the world). Although many women of this time were challenging previous ideas of femininity and sexuality (which itself marked a significant advancement of women’s rights), in the measure that they increasingly engaged in public life, they were constrained all the more strictly by the anxieties surrounding the maintenance of a good physical image. Women were beginning to be held to nearly impossible standards. According to Arnold, women today must be “both virgin and whore, clean and pure, yet manipulative and dangerously sexual beneath a façade of artificial charms,” all while adhering to the cultural standards of physical beauty.22 Women, not only in fashion magazines, but in daily life as well, have constantly been sexualized and objectified for wearing certain clothing. A woman could be dressed with the intent of finding personal liberation and satisfaction and immediately be reduced to an object by an observer, which greatly complicates the argument that fashion truly can liberate women from the patriarchal norms of society. Arnold writes of “correct” and “incorrect” clothing, arguing that “the idea that revealing clothing represents dubious morality is too firmly embedded in western culture belief to have been completely erased by calls for women to empower themselves by reclaiming their bodies through what they wear.”23 Despite the constricting ideals of moral dress, eroticism emerged in the 1960s as a way to reconstruct moral codes to mock the styles of the previous decade that were centered on archaic ideals of femininity. Eroticism sought liberation through fashion in allusions to sexual play. With this rise of eroticism came increasing sexual imaging of women in magazines and, at the same time, an increasing push for gender equality. A woman may feel liberated in wearing an erotic outfit, but the societal perception is still that she is a slut or in search of male attention.

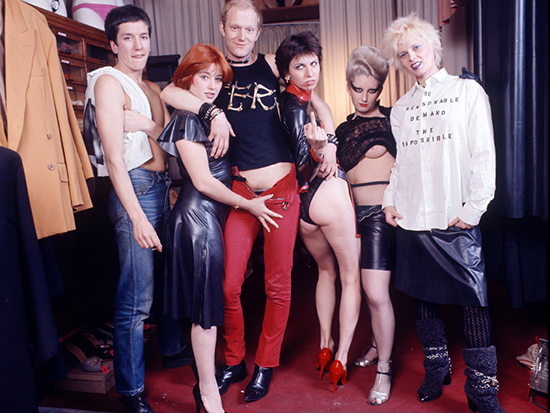

In the 1970s, as eroticism took hold, “sex became more glamorous,” but also “more threatening.”24 This idea of owning one’s sexuality spread to teenagers, with the appearance of fetishism in teen fashion—latex, buckles, and zippers became trendy. Teens did not want to create an image of submission, but rather to “challenge the soft sentimentality usually assigned to female teenagers.”25

These forms of overt sexuality threatened men because they symbolized women breaking free from their constraints and seeking to destabilize gender norms. Caroline Evans finds this represented in the symbol of the sexualized Medusa, which emerged in the mid to late 1900s. What began as an image of a terrifying woman who could turn men to stone gradually morphed into the image of a beautiful, “seductive temptress” who served as “an emblem of the dangerous power of women.”26 The Medusa represented an exaggerated symbol of female sexuality—one stemming from male fears of the time. There was a demonic quality attributed to female sexuality as women began to claim their bodies and their clothes as their own; it was a new femininity, not one produced by male desire, but one representing the female as an autonomous being. But does the increasing sexual imaging of women and threatened reaction of men tend toward the liberation of the female form, or does it keep us chained to the sexualization and objectification of our bodies?

Female sexuality becomes, through fashion, more than threatening—it is a form of liberation and power for women, contradicting the notion that expressing one’s sexuality and dressing in clothes that seem to be “immoral” do nothing more than put women back into the shadow of men to be objects of their desire. Designers John Galliano and Alexander McQueen both explore female sexuality, but in almost completely contradictory ways. Galliano is quoted in Alison Bancroft’s Fashion and Psychoanalysis: Styling the Self as attributing the motivation for his designs to women’s ability to be desired:

I want people to forget about their electricity bills, their jobs, everything. It’s fantasy time. My goal is really very simple. When a man looks at a woman wearing one of my dresses, I would like him basically to be saying to himself: ‘I have to fuck her.’ […] I just think every woman deserves to be desired. Is that really asking too much?27

What this statement portrays is the common belief that a woman’s worth rests entirely on her being desired by a man—the belief, in other words, that women live, dress, and act in order to achieve the honor of being sexually attractive to the opposite sex. Allison Bancroft underscores the absurdity of Galliano’s words in pointing to his “peculiar idea that a woman should take a man’s desire to penetrate her with his penis as a compliment.”28 Galliano, born in 1960, is undoubtedly a successful designer, one who graduated with a first-class honors degree in fashion from Central St. Martins School of Art and later served as head designer at both Givenchy and Christian Dior. His designs, though skillful, seem to point to women as the “object of desire for man” and refer to female sexuality as inherently dangerous and destructive.29 In his Autumn/Winter 2004-2005 collection for Dior, he built upon the same kind of femininity that Dior himself and Charles Worth before him had emphasized in their designs—one fraught with archaic and misogynist themes. This collection reached back to the New Look (the designs by Dior, in 1947, that focused on past ideals of femininity with attributes such as thin waists, full skirts, and shaping underwear.). Galliano’s clothes were designed to draw attention to the breasts and hips—making them seem larger than they actually were, making the waist seem smaller, and restricting motion with heavy skirts. His designs “emphasize[d] the physical aspects of a woman’s body that are different to a man’s (hips, breasts, etc.) in order to suggest that difference is both inevitable and anatomically defined.”30

This emphasis on the ideally “natural” feminine form highlights the line between male and female, allowing for further separation of the sexes. If women are expected to dress in clothes that accentuate their differences from men, is it not even more difficult to equalize men and women? I do not mean to suggest that differences between the sexes should be erased, but rather that a fashion collection focused on manifesting these differences in terms of male desire should be challenged. In Galliano’s clothes, one sees that “the woman herself does not exist.”31 She is simply there to be desired, nothing more; her sexuality is on display only so that she will catch the male gaze. I do not mean to suggest that women cannot wear clothes (such as Dior’s) that show off the feminine form, or, rather cannot seek liberation in fashion. It is in viewing his collection through his own statements of intent that one finds issue. It is his explicitly stated wish to establish the wearers of his clothes as objects of male desire—an absurd and oppressive wish.

Alexander McQueen, a designer of similar caliber to Galliano, was born in 1969 and attained a Master of Arts in fashion design from Galliano’s alma mater. He followed Galliano at Givenchy and went on to establish his own line. McQueen’s designs explore concepts of feminine sexuality in considering fashion’s interaction with the body and desire. Caroline Evans quotes McQueen in his discussion of the intents of his designs:

I design clothes because I don’t want women to look all innocent and naïve, because I know what can happen to them, I want women to look strong.

I don’t like women to be taken advantage of. I disagree with that most of all. I don’t like men whistling at women on the street, I think they deserve more respect.

I like men to keep their distance from women, I like men to be stunned by an entrance.

I’ve seen a woman get nearly beaten to death by her husband, I know what misogyny is . . . I want people to be afraid of the women I dress.32

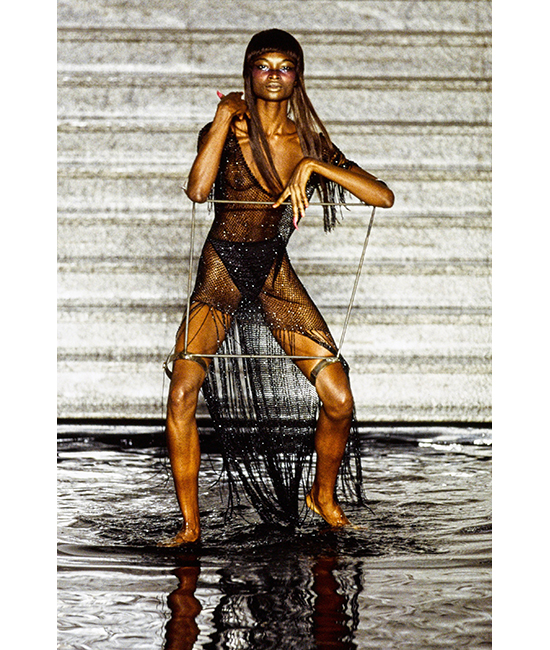

In these quotes, McQueen acknowledges the cruelty and abuse that women face in their lives—being catcalled, being beaten, being raped, being treated as objects. His designs display just this. He draws attention to the severe limitations placed upon women and generates a sexuality and femininity that is cruel, frightening, aggressive, real, and brutal (one much different from the softly submissive ideas of Dior). Rather than shying away from the brutality of the world, McQueen embraces an “aesthetic of cruelty” in order to stage a feminine resistance within what is available.33 Critics often accused him of misogyny because of the highly dramatic and violent references in his designs, but McQueen’s aim was instead to mirror the harsh realities of the real world. In particular, in his collection La Poupée for Spring/Summer 1997, McQueen presented a ridiculous, but attention-grabbing accessory: a square metal frame attached to the model’s legs and arms, inhibiting any natural movement.

This frame is an exaggeration of the same concept embodied in the heel or the corset. Why are women expected to walk normally in heels and breathe normally in the corset when they are just as absurd as a square metal frame connecting your limbs? The metal frame is absurd only because it does not enhance the female figure in male terms. Ultimately, McQueen created collections that gave women a dangerous sexuality—not the dangerous sexuality attributed to the Medusa, the object of male fears, but rather a sexuality that itself elicits fear. He did not create women to be objects of desire, but created them to be sexual beings: to be women outside of the gaze of men. McQueen does not objectify the body in his violent designs, but rather allows women the space to reclaim their own sexuality, which had been distorted and claimed by men. He does not ignore the cruelty of the world, but puts it on the female body for display.

We, as women and allies, have striven to allow self-expression to be free from gender norms, cultural norms, and the inequality pervading our perceptions of both male and female sexuality. Yet it seems that in my own experience of being a modern, twenty-first-century woman, I have found myself struggling to escape those norms and perceptions. As I rush down Third Avenue in the pouring rain, no rain coat, red faced and sweaty from a workout, I hear a man whistle and call out to me, “hey, baby.” As I walk to class on a fall day, my entire body protected from the cold air, I find myself standing still as a man stops in front of me and tells me, “I just wanted to tell you that you’re beautiful . . . I love your tights.” Just a few minutes later, as I wait for a friend in the park, I look up as a man approaches me to compliment the way my skirt “accentuated my legs.” In these instances, it seemed as if the clothes I wore, no matter their function or value to me, were there to attract the male gaze. It seems absurd that despite women’s long struggle to gain equality, through which we have gained civil rights, legal protections, and so forth, we still live under a society that jokes about rape, catcalls women on the street, objectifies the female body, sexualizes her clothing, and places her worth in the hands of men. It seems absurd that despite our long fight, women are still slaves to the fashion system and its constructed ideas of femininity. However, it is not absurd to seek change—to seek the liberation of women, in part by allowing women to dress according to their own rules, not those constructed by men in order to keep women in an inferior place, so that they can “grab them by the pussy.”34

- Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi. We Should All Be Feminists. New York: Anchor Books, 2015.

- Veblen, Thorstein. The Theory of the Leisure Class. Edited by Martha Banta. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 20.

- Fields, J. “‘Fighting the Corsetless Evil’: Shaping Corsets and Culture, 1900-1930.” Journal of Social History 33, no. 2 (1999): 355-84. doi:10.1353/jsh.1999.0053, p. 356.

- “Feminine Equinism.” British Medical Journal 1, no. 2987 (March 30, 1918): 378. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20309761, p. 378.

- Wilson, Elizabeth. Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity. 2nd ed. London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2013.

- Simmel, Georg. “The Philosophy of Fashion.” Translated by Mark Ritter and David Frisby. In Simmel on Culture, edited by David Frisby and Mike Featherstone, 187-206. London, Thousand Oaks, and New Delhi: SAGE, 1997, p. 196.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 96.

- Arnold, Rebecca. Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2001, p. 3.

- Ibid., p. 65.

- Ibid., p.6

- Ibid., p. 63

- Wilson, Adorned in Dreams: Fashion and Modernity, p. 230.

- Ibid.

- Ibid., p. 231.

- Arnold, Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century, p. 65.

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London and New York: Routledge, 1990, p. 10.

- Ibid., p. 24

- Ibid., p. 17.

- Evans, Caroline. “Masks, Mirrors and Mannequins: Elsa Schiaparelli and the Decentered Subject.” Fashion Theory 3, no. 1 (1999): 3-32, p. 7.

- Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity, p. 175.

- Arnold, Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Morality in the 20th Century, p. 66.

- Ibid., p. 68.

- Ibid., p. 74.

- Ibid., p. 77.

- Evans, Caroline. Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2003, p. 122.

- Galliano, John qtd. in Bancroft, Alison. Fashion and Psychoanalysis: Styling the Self. London and New York: I. B. Tauris, 2012, p. 59.

- Bancroft, Alison. Fashion and Psychoanalysis: Styling the Self. p. 62.

- Ibid., p. 89.

- Ibid., p. 90.

- Ibid., p. 91.

- McQueen, Alexander qtd. in Evans, Fashion at the Edge: Spectacle, Modernity and Deathliness, p. 149.

- Ibid., p. 141.

- Mathis-Lilley, Ben. “Trump Was Recorded in 2005 Bragging About Grabbing Women “by the Pussy”.” Slate Magazine. October 07, 2016. Accessed December 23, 2016. http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2016/10/07/donald_trump_2005_tape_i_grab_women_by_the_pussy.html.