When I began my time at an early twentieth-century historic house museum, I was expecting to find a lot of things—furniture, yellowing diaries, shelves and shelves of vintage clothes—but I never imagined I would find my grandmother.

A Note for the Archive

When I began my time at the McFaddin-Ward House, an early twentieth-century historic house museum located in my hometown of Beaumont, Texas, I was expecting to find a lot of things—furniture, yellowing diaries, shelves and shelves of vintage clothes—but I never imagined I would find my grandmother. A few weeks in, however, while rummaging through the archive, I found her, stumbled over her, practically. Her name was Mildred, and she was born in Orange but lived in Beaumont most of her life. She was a member of one of the first docent classes here at the McFaddin and dipped her hands into many other local history organizations, all facts I’d heard my mom recite in the kitchen over the years, but not ones that struck me until now. She passed away when I was young, and all I have left of her, really, is some jewelry and a raincoat and occasional remarks from people I encounter only briefly about how much they admired her. I try to piece them together to find some way to know her.

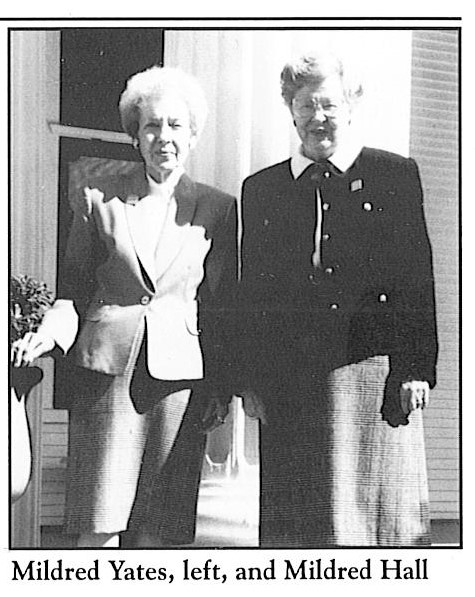

It was a random Thursday in the archive that I found her. She was sitting in a filing cabinet—impatiently, I imagine—with almost two hundred others, all waiting to have their say. I put her transcript through the scanner, carefully, and placed her cassette tape into a tiny machine that would convert her into an MP3 file so that she’ll have a new home in the computer. The oral interview, conducted by the museum’s resident historian Judy Linsley in 1998, records the memories of life in early Beaumont from my grandmother and her lifelong friend, also named Mildred. I didn’t remember her voice sounding so high and friendly. I felt lucky that someone captured it and put it someplace safe.

Of course, it wasn’t luck that saved my grandmother’s voice but a consistent and attentive oral history project that was undertaken at the McFaddin-Ward House in the 1980s and ’90s. There are over 200 tapes with interviews featuring a vast array of people—relatives of the McFaddins, former employees and their relatives, cowboys, nurses, and the descendants of prominent pastors and school teachers—and during the spring of 2021, it was my job to digitize the tapes and their transcripts. I am thankful that the archive has welcomed them.

The project I’ve created for the McFaddin-Ward House is called “A Note for the Archive.” I think of it as a curated digital archive and a physical research essay, but really, it is simply a driving tour of Southeast Texas housed in a virtual, interactive map on Google Earth with plot points in Jefferson, Chambers, and Galveston Counties. These locations are depicted using a mixture of empirical sources, such as newspaper articles, photographs, and historical markers, and non-empirical sources, like objects from the museum’s collection and oral histories from the archive. In this project, the physical landscape becomes an exhibition space, the locations become historical artifacts, and the diverse, vernacular voices from the oral histories become tour guides, storytellers, and historians. The aim of this project is, first and foremost, to expand the McFaddin-Ward House’s collection and archive beyond the walls of the museum and into the surrounding community. Because really, when we talk about the McFaddin family, we talk about all of Southeast Texas during the early twentieth century. We talk about rice farming, ranching, and oil. We talk about gender, class, and racial divide. We talk about technological, social, and cultural change, and we even talk about the politics of owning land and collecting land, and we think about where it came from. Another goal of this project is to question the ways history is traditionally taught and created, to explore the political and personal implications of allowing a history to be told using first-person testimony, and to challenge the ways we look at the world around us, which is just one layer in a silly little lasagna of history beneath us that houses histories both known and unknowable. It is literally a long, winding journey made of unanswered questions!

A major theme I explored while conceptualizing this project was the ways an archive can become complicit in the misremembering, bias, and erasure often tied to structures of power. Griselda Pollock, in Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive, describes a “fetishism” of the archive created from the assumption that history can be pieced together and known through fragments, which inherently is what an archive (and a museum) is: a collection of fragments.1 Pollock explains that archives are “pre-selected in ways that reflect what each culture considered worth storing and remembering, skewing the historical record and indeed historical writing towards the privileged, the powerful, the political, military and religious. Vast areas of social life and huge numbers of people hardly exist, according to the archive.”2 Thus, archives often exist simply as reproductions of the structures of power that created them.

And the stakes of this reproduction are by no means low. Pollock explains that our understanding of the past informs our understanding of ourselves, which ripples through the kind of future that we are able to create. And through our attempts to know an unknowable past, “we become spies, voyeurs, subject to fantasies and identifications, idealisations and misrecognitions.”3 In many ways, through an over-zealous reliance on the archive, history can cease to resemble the cut-and-dried empirical process we want to believe it is. In many ways, history will never live up to those standards. And in many ways, history is not much more than a culturally-created story that we tell ourselves.

However, daring to fantasize beyond the limits of the archive can, in fact, be deeply radical, precious work. In her essay “Venus in Two Acts,” Saidiya Hartman grapples with the constraints of the historical archive and what it means to imagine something beyond its limits by writing “a history written with and against the archive.”4 In works such as Lose Your Mother and Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals, Hartman aims to tell what she calls “impossible stories,” the tales of people not preserved or valued in the archive, specifically Black and enslaved women.5

In “Venus in Two Acts,” Hartman describes a brief encounter in the archive, through diary entries and court documents, with two young enslaved women who were murdered by a ship captain on their journey through the Middle Passage. Hartman explains that “the stories that exist are not about them, but rather about the violence, excess, mendacity, and reason that seized hold of their lives… The archive is, in this case, a death sentence, a tomb, a display of the violated body.”6 For Hartman, “it is tempting to fill in the gaps and to provide closure where there is none. To create a space for mourning where it is prohibited. To fabricate a witness to a death not much noticed.”7 This dream of witnessing is at the heart of Hartman’s work, which dares to gather the pieces and imagine what the real stories of these two girls was really like. Hartman imagines conversations and light touches of the hand aboard the ship while asking:

Is it possible to exceed or negotiate the constitutive limits of the archive? By advancing a series of speculative arguments and exploiting the capacities of the subjunctive (a grammatical mood that expresses doubts, wishes, and possibilities), in fashioning a narrative, which is based upon archival research, and by that I mean a critical reading of the archive that mimes the figurative dimensions of history, I intended both to tell an impossible story and to amplify the impossibility of its telling . . . This double gesture can be described as straining against the limits of the archive to write a cultural history of the captive, and, at the same time, enacting the impossibility of representing the lives of the captives precisely through the process of narration.”8

Hartman’s “double gesture” reveals both the futility and the hope in a fragmented archive and relishes in Pollock’s “idealisations” in attempting to know the unknowable.9 When the game is rigged, does it matter if one breaks the rules?

Hartman’s insistence upon the luxury of bearing witness to one’s own life is inherent in any collection of oral histories, thus, using oral history and personal testimony as a way of depicting and describing the past can act as an expansion of a more accessible archive by diversifying both its storytellers and its methods of research. At the McFaddin-Ward House, we are lucky to have the tape-recorded personal histories of members of the Beaumont Chauffeur’s Cub—founded sometime between 1906 and 1912 (oral testimony in the archive is not in agreement) by two of the McFaddin family’s chauffeurs, Tom Parker and Andrew Molo, and thought to be the oldest Black club in Texas—and of Charles F.L.N. Graham, Jr., the son of a prominent minister in Beaumont of the same name, who founded a church, a hospital, and a campaign to encourage voting in the Black community. These two histories describe in great detail a vibrant social world integral to Beaumont’s history that is not immediately available in a typical tour or interpretation of the McFaddin-Ward House, and their presence in the collection effectively expands the museum’s reach throughout the community.

Oral histories also allow for an unveiling of untold perspectives towards community events that local historians and community members know much about. Most people in Beaumont are familiar with the famous Lucas Gusher of 1901 that discovered so much oil at Spindletop Hill that it shot through the top of the derrick and rained for days. The story of Spindletop still has deep ties to present-day Beaumont, to its prominence among port cities, to the scattering of refineries around the area, and to the very fortune that allowed the McFaddin-Ward House to be the house it is today (the land of Spindletop Hill was partially owned by the McFaddins). But Ethel Alice Slauson, a 95-year-old Beaumont resident whose family moved to Gladys City, the boomtown that cropped up around Spindletop, when she was a child, offers an elaboration on a different perspective of the events. In her oral interview, which was conducted in 1989 by Lamar University but is stored in the McFaddin’s archive, Slauson describes the frequent climbing of the oil derricks with her siblings, playing hiding and seek in boilers, and digging her own “wells” along the hill to see what oil she and her friends could find. The vibrant scenes she describes of Gladys City, coupled with familiar tales of a rambunctious childhood, make the story of Spindletop come to life and make it relevant in ways that were not obvious before.

The oral interviews also allow fresh views and interpretations of the McFaddin-Ward House Museum, the people who lived there, and the objects in the collection. Doris Catrett, a nurse who helped look after Ida Caldwell McFaddin in her final illness, describes a kind, thoughtful woman despite the difficult state her illness put her in. Hearing details about real-life discussions and interactions—personal ones, too—that took place in the house brings a new urgency to the rooms through which we tour. Most striking, though, is Doris’s remembrance of a tiny black frame on Ida’s desk displaying the phrase, “What would Jesus do?” The frame is still there, on the far wall of the master bedroom, just below the window, and has likely been unmoved since Doris sat in that pink bedroom decades ago. When I see the frame there, now, I am reminded of the life and relevancy of the room, that although styles, customs, cultures can change, the reverberant act of sitting with a sick person to keep them company never will. It is something like a real-life, three-dimensional version of Roland Bartes’ punctum, an element in photographs which he defines as a “sting, speck, cut” or that causes a “prick” in the viewer.10 This object, with the help of an oral interview that adds a much deeper, more universal context, pierces a little deeper in me than others do.

However, just as we question the archive, we should also question the interviews themselves. Pollock explains that “beyond what we can monitor in ourselves is the unconscious, always at work, itself an inaccessible but active archive” that is both highly personal and culturally created due to the perspective we inherit from the culture in which we are raised.11 How can we trust our own memories, anyway? An interesting example is the dilemma of the Texas Ice Palace. The Texas Ice Palace was an ice-skating rink in Beaumont that was owned and operated by Texas Ice Company, which was in-part owned by Carol Ward, Mamie McFaddin’s husband. This much we know is true. What is uncertain, however, is whether there was also a roller rink in Beaumont, and if so, where it was, and whether it, too, was owned by Texas Ice Company. There are a variety of oral interviews in the archive that mention Texas Ice Palace, and each has a different version of events. One person claims that Texas Ice Palace was converted into a roller rink during the summers, and one claims that the roller rink was entirely separate from Texas Ice Company and was just down the street; another claims that there was no roller rink at all, and yet another woman says that she met her husband there. Each of these people, too, was entirely convinced that they were right. This seems trivial, but if there is this much persistent disagreement about the existence of a building, what can we make of the accounts of deeply nuanced personal sentiments about large-scale events?

There is a moment, too, in Slauson’s interview about Spindletop when she misspeaks the year of her birth, which she had mentioned previously, and in his interview, Casey Jones, a former farmhand at the McFaddin’s ranch, mentions offhandedly that he is not feeling his best that day and likely is not making much sense. A final interview with Cecelia Smith, Mamie’s longtime employee and friend, is nearly incomprehensible due to an illness that affected her speech; its transcript is covered with dashes to mark the words that cannot be made out. Both Jones and Smith passed away soon after their interviews were conducted and were not able to line-edit the transcripts. In these cases, how do we reckon with the discrepancies among personal accounts of history?

We cannot forget that oral interviews, just like the archive itself, express very specifically situated perspectives and sentiments. While the fact that “folk history is an extension of personal history” is a benefit and a gift, it is something that should be continually called into question.12 In her essay “Death of a Priest: The Folk History of a Local Event as Told in Personal Experience Narratives,” Yvonne Lockwood discusses both the relevance of personal stories in creating community and individual identity and the ways these stories are complicit with the biases of their creation:

The memory of the past includes both ‘facts’ and attitudes regarding the remembered period. These remembrances, however, are continually integrated with the present, with changing attitudes, reinterpreted and even reworked. Therefore, it is quite possible that the folk history, composed of various shared traditions, may not reflect what actually happened in the past at all. This is not important for our purpose. What is important is that the folk history is a statement about individual and collective concepts and beliefs concerning what happened. Folk history, then, communicates a world view. Not only does the past shape the present, but the present also shapes the view of the past.13

The “worldview” that Lockwood references in this passage is a common term in anthropology that is loosely defined as the perspective of the world that a person carries with them based on the culture in which they were raised. In this way, Lockwood reveals that the purpose of folk history often is not to analyze the past but to discover the cultural purpose of recording and learning from and teaching the past. This is closely related to Pollock’s argument of the archive’s mediation by the culture that creates it, and both suggest that history is not much more than a cultural creation that we use to tell stories about ourselves and that this cultural knowledge dictates the ways we act in the present day. This kind of context should not be lost on us as we navigate an archive full of cultural perspectives.

In creating this virtual map for the museum, I have collected and sorted excerpts from oral histories, objects from the McFaddins’ collection, and typical archival materials, like photographs, newspaper articles, and historical markers. Where relevant, I have also included links to external sources that offer more information about the site or subject and photographs of the site in the present day. In doing so, I hope to call into question the various ways we have of creating history and telling stories, and the ways they elaborate, qualify, and expand upon the other. Also, using these various sources to describe objects, I hope, will make the museum’s collection come to life and exist in a space beyond the walls of the house and the storage facility and into the greater community. And I hope the objects and archival materials will bring to mind what is lost or remembered when we listen to the oral stories that are told around us every day.

I have also organized all of these materials around a map of Southeast Texas. This is meant to anchor these ideas and subjects to the roads and buildings that we pass every day in order to serve as a reminder that history lies beneath us and all around us at all times, even if we don’t realize it, even if it is not reflected in the archive. As anthropologist Keith Basso writes in Wisdom Sits in Places, his ethnography about the Western Apache:

In modern landscapes everywhere, people persist in asking, ‘What happened here?’ The answers they supply, though perhaps distinctly foreign, should not be taken lightly, for what people make of their places is closely connected to what they make of themselves as members of a society… If place-making is a way of constructing the past, a venerable means of doing human history, it is also a way of constructing social traditions and, in the process, personal and social identities. We are, in a sense, the place-worlds we imagine.14

Basso describes the Western Apache practice of naming landmarks in their environment based on stories of events that once happened there, stories that often are culturally-rooted and are not set within a measured year or time period (such is a Western Apache way of making history). The Western Apache, Basso explains, use these place names to anchor culturally-held values and moral and behavioral expectations to the physical environment, and they also use these place names in conversation as metaphorical devices to discuss the stories and sentiments they relate to. Thus, by using a map, I want to consider what it means to see history and stories in the world around us and the ways that cultural knowledge and identity can be stored in the physical world, much like they are preserved in the archive and its personal stories. In using a map, I also want to stop and consider the luxury of living on the grounded landscape that our stories come from. There are stories far, far beneath this land, those of life centuries and centuries and centuries ago that have no weight in our historical record, not even the scraps that Saidiya Hartman stumbled upon in the archive. Though we cannot know them, we must not forget them.

As I sit and consider the work that I was part of at the McFaddin-Ward House, I wonder why I felt so captivated by histories that, relatively speaking, are fairly unremarkable. In many ways, Beaumont is just a regular old city, perhaps one crumbling from its earlier glory. But I can’t keep from coming back, again and again, to stories of the everyday. Every day spent in the archive is like an act of prayer to this invisible, unattainable insistence upon the power of each normal person to enact change in their communities, to form meaningful connections, and to say and do valuable things. Whether we call it microhistory, folk history, or anything else, the preservation of oral histories and personal testimonies, and the insistence upon their validity as primary sources, is a radical subversion of the archive and the ways that history is typically created. But also, I believe—perhaps as a result of my own socialization within a specific culture—that when we understand our history, we can better understand ourselves.

I’m thinking, again, of my fragmented archive of my grandmother. Like the physical archive at the McFaddin-Ward House, it is made up of a collection of objects, remembrances, and a fading memory, but now I have an oral history to add to the files. This audiotape certainly does not complete the collection, does not bring back the words she whispered and the way she once held my hand, but I still feel lucky to have it. When I put in my headphones and listen to her talk about how they used to wash clothes in the 1930s, I relish in the fact that no amount of magnetic tape and paper will allow me to know her. I almost feel closer to her because of that. At any rate, I invite you to visit the archive, any archive. It belongs to us, and it encompasses us. You may have a relative or a friend there, and if you don’t, you should, but I promise that, in the mess of things, you may find something of yourself. The stories we tell, no matter how unavoidable their complicity, are worth telling, worth trying to remember, worth marking in the dirt somewhere, as long as we never stop questioning, doubting, dreaming of another way.

- Griselda Pollock, “What the Graces Made Me Do . . . Time, Space and the Archive: Questions of Feminist Method,” in Encounters in the Virtual Feminist Museum: Time, Space and the Archive (Routledge, 2007), 12.

- Pollock, “What the Graces Made Me Do,” 12.

- Pollock, “What the Graces Made Me Do,” 12.

- Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 12, no. 2 (2008), 12.

- Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 11.

- Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 2.

- Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 8

- Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” 11.

- Pollock, “What the Graces Made Me Do,” 12.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Translated by Richard Howard, (Hill and Wang, 1980), 27.

- Pollack, “What the Graces Made Me Do,” 12.

- Yvonne A. Lockwood, “Death of a Priest: The Folk History of a Local Event as Told in Personal Experience Narratives.” Journal of the Folklore Institute 14, no. 1/2 (1977), 98.

- Lockwood, “Death of a Priest,” 98.

- Keith Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places (University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 7.