A case for why the mental health gurus on TikTok may be doing their adolescent viewers more harm than good, as well as why these adolescents are drawn to it anyway

A Perspective on TikTok’s Mental Health Epidemic

Abstract

Since the outset of the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been an outpouring of videos focused on mental health or neurodivergence on TikTok, created mostly by laypeople and non-licensed “mental health advocates.” I argue that although these widespread videos and online discussions may appear beneficial for the destigmatization of mental illness, they are actually laced with misinformation, detrimental to the public’s understanding of mental illness, and influenced more by public figures’ opinions, likes and shares than clinical facts. Moreover, as viewers and mental illness advocates collectively form “sides of TikTok,” or smaller TikTok communities that center on specific mental illnesses, they enable adolescents to dangerously adopt these illnesses as personal identities.

Introduction

As an avid evader of everything related to TikTok—the popular video sharing app that has dominated the age 10-29 demographic since early 2020—I only recently discovered the extent to which TikTok circles teem with mental health professionals, advocates, and self-proclaimed gurus. The grapevines of Instagram Reels alerted me to the massive and growing communities of these mental health aficionados, who have seemingly grouped themselves by illness using catchy hashtags to the likes of #depressed, #anxiety, and a new fan-favorite, #tourettes.

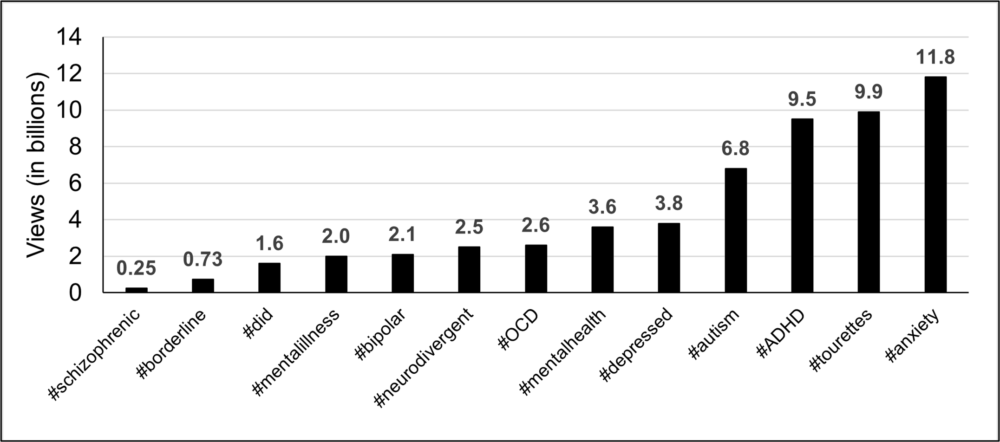

As of February 17, 2022, TikTok videos tagged with major neuropsychological conditions had over 50 billion cumulative views (fig. 1) by the app’s audience of one billion monthly active users.1 Fifty billion views is immense by any standards. But, the figure is especially staggering if one considers that the lifetime prevalence rates of four out of the five most viewed disorders are below five percent internationally, at least according to systematic reviews of clinical research performed in the 2010s.2 3 4 5 Not to mention, much social stigma surrounds the diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses, especially for individuals in low socioeconomic areas.6 Thus comes the question of why TikTok communities seem so apt to spread awareness and testimonials of mental illness when the rest of the world apparently doesn’t.

I entertained three possible explanations of the discrepancy between contemporary TikTok and the systematic reviews of yore:

- TikTok is eroding the social stigma associated with mental illnesses one easily digestible, rapid-fire information nugget at a time.

- Psychologists, psychiatrists, counselors, and all manner of shrinks have migrated to TikTok, begun spreading awareness of all kinds of mental afflictions, and are now rapidly multiplying.

- We have a mental health epidemic on our hands, in which TikTok users are now a vulnerable population with particularly heightened susceptibility to rare psychological and neurological conditions.

None of these possible explanations seem particularly satisfying or plausible (though the potential for rapidly multiplying shrinks is wildly exciting). Nevertheless, being a student of the sciences and a strong proponent of Popperism, I’m of the belief that we ought to give them each a sporting chance and examine them by way of falsification.

The Online Selection of Mental Illnesses to be Popularized

First, I will examine the video content on TikTok. Are the majority of content creators underneath these mental illness hashtags spreading accurate, peer-reviewed clinical information? Moreover, to what extent do the trends in the TikTok mental health communities, often called “sides of TikTok,” generally align with societal trends in the perception of mental illnesses?

To answer these questions, let’s begin with the case of a neurological syndrome like Tourette’s, which affects 0.05 to 3.00 percent of individuals, depending on country of origin.7 Tourette’s is often the subject of social stigma rather than social awareness,8 yet has a mammoth of a following—nearly 10 billion views—on TikTok (fig. 1). This would suggest that TikTok may genuinely have a positive influence on the lives of those with Tourette’s, normalizing their symptoms (such as tics). Additionally, it may suggest that TikTok is providing a platform for creators to increase online exposure to and educate neurotypical viewers (i.e., those who do not have Tourette’s) on the syndrome, thereby reducing the stigma associated with it.

Unfortunately, these videos had the unforeseen side effect of previously neurotypical teen TikTokers also developing similar, Tourette-like tics upon watching them. Among these viewers, there was a dramatic up-tic (pun intended) in instances of unusually frequent, often self-injurious and involuntary tic behaviors that were quite distinct from the typical Tourette phenomenology, leading researchers to conclude that it was a “mass sociogenic illness,” or an illness engendered by social influences online.9 Just how TikTok led to the propagation of this sociogenic illness may be explained by the format of the “mental health” videos themselves.

Based on a cursory survey of the content available on TikTok, I’ve found that the majority of its mental illness related flicks fall under one of two categories, the first being more traditional verbal explanations of disorders and the second being what its creators call “POVs” or points-of-view. The latter videos are created to stimulate and give exposure to the first-person experience of different mental illnesses. In each video, the subject may go about their day showing visible signs of a particular mental illness or exaggerate their symptoms on camera to showcase their severity. These videos resemble the roleplay-like “POV” videos created by other neurotypical TikTokers who reenact or fictionalize their own past experiences or those featured in popular media, like social media or television. As one might expect, under the “Tourette’s side of TikTok,” many of these POVs feature young teens acting out their tics, with little to nothing distinguishing the sociogenic or psychosomatic symptoms from the neurological ones. The majority of these are not mental health professionals but young performers.

It is hypothesized that sufficiently frequent online exposure to this medley of tic types, in combination with social stressors invoked by the COVID-19 pandemic and other psychological comorbidities (like existing mental illnesses) contributed to adolescents spontaneously mimicking and developing tic and movement disorders.10 11 Beyond normalizing Tourette’s syndrome to the extent of destigmatization, these videos seemingly over-normalized the syndrome enough to make it seem like any typical fad that adolescents, unconsciously or consciously, seek out.

Observing the Tourette’s side of TikTok conjures up distant memories for me about the millennials on Tumblr, a blogging site popular in the early 2010s. The site’s main user base of then-teens engaged in similarly destructive mental illness-focused communities, carving out spaces that romanticized depression, suicide (which they termed “fallen angelhood”), anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychological disorders in their blog posts and fanfiction aplenty.12 For instance, for about half a decade, photographs of anorexic women became online “thinspiration,” or an inspirational epitome of beauty in thinness, rather than a debilitating psychological disorder, with many first romanticizing anorexia to the point of being #proana (pro-anorexia) and developing symptoms of it.13 Glamorized portrayals of mental illness in cyberspace turned medical conditions into fantasies totally unlike their real-world counterparts, enrapturing these highly suggestible teen Tumblr users to the point that they ignored the real-world consequences of the self-harm in which they partook.14 Of course, many eventually discovered the error of their ways. But many of them did not lose their eating disorders or depressive symptoms upon their departure from these Tumblr communities, struggling in the years after to recondition themselves away from their past negative thoughts and behaviors.15 It is still unclear whether the modern psychogenic tics of TikTok will pose similarly long-lasting detriments. But, for the good of those suffering from them, I do hope not.

The online craze over these tics also reveals how very particular mental illnesses are curated to and watchable by an online audience. Considering how easy it is to visually observe and identify a tic, Tourette’s proves to be one of the most watchable neurological ailments, its symptoms easily consumed and understood by viewers with little to no psychiatric education. Its view count is also over an order of magnitude higher than that of schizophrenia, a neuropsychological illness often synonymous with hallucinations that has an international prevalence of just over half that of Tourette’s. The massive disparity in view counts can be explained by the fact that unlike tics, the hallucinations and delusions associated with schizophrenia are only knowable to the individual themselves, unable to be captured on camera and arduous to simulate by neurotypicals.

From this, I can gather that the TikTok user base and algorithm are extremely choosy about what kinds of mental illness have the potential to be destigmatized, and the view rates on the platform are far from matching the real-world prevalence of each condition. There appear to be two main factors that enable an illness’s online marketability: ability to be shown on camera and relatability or appeal to a neurotypical audience. The view counts speak for themselves. Depression and anxiety disorders are among the most viewed illnesses, since their isolated signs and symptoms, such as anxious or low mood, can be so widespread that many creators and viewers alike can relate, even without meeting the criteria for a genuine, differential clinical diagnosis. The fact that they have been the subject of online glamorization since 2010s Tumblr further contributes to their over-normalization and appeal. In addition, ADHD and high-functioning autism seem to be perceived less as stigmatized illnesses and more like relatable personality quirks of an otherwise sound mind. And finally, dissociative identity disorder (DID) can be glamorized on camera, with TikTokers performing as though they are spontaneously switching between “alters” or identities. Schizophrenia was decidedly never cool, never observable, and too much of an impediment to daily life for those being treated for it to gain and preserve a following on the app.

And therein the issue lies. TikTok, though it may have reduced the stigma surrounding particular mental illnesses, is far from a paragon of new-age psychiatric education. It is not immune to the lack of social understanding and awareness related to more serious conditions. These videos are not reflective of trends in society but simply trends in the use of visual media and digital space. POVs also reflect adolescents’ desire to explore a world that isn’t their own, especially with the pandemic still looming in the backdrop of everyone’s reality, whether they choose to admit it or not.

The Producers and Accidental Propagators of Misinformation

This brings me to the question, what of the rapidly multiplying TikTok content creators? Many of the most popular creators are not healthcare practitioners but self-professed patients and “mental health advocates” who speak about psychiatry without a degree in sight. Why do the latter enjoy making and watching mental illness related videos in the first place, especially since some don’t strike me as particularly keen on preserving the integrity of the mental health “information” they spread? Many of them represent something akin to an invasive species, imposing a culture of influencers and arbitrarily popularized public figures in a community supposedly based in public education and awareness.

Several of these media personalities have become the face of their diagnoses online, such as Connor DeWolfe for ADHD and The A System for dissociative identity disorder (DID). For some of these individuals, while the information they spread about their conditions may be truthful to their own first-hand experiences, it may prove misleading to others, especially for their young viewers who may relate to and co-opt the disorder without waiting for a formal diagnosis. Many of these psychiatric disorders are also subject to a great deal of individual variation, especially in relation to gender, culture, or socioeconomic status.16 Thus, it becomes problematic when a single public figure amasses a large audience of viewers and suddenly becomes the spokesperson for an illness on which they may not be clinically educated. The TikTok education on that illness suddenly falls victim to a kind of tunnel vision.

In some cases, the spread of misleading mental health content can’t definitively be blamed on the creators themselves. For example, Connor DeWolfe was, in fact, clinically diagnosed with ADHD and works to provide video content about his experience with the disorder that aligns well with what has been described in the most recent Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), albeit dramatized or exaggerated at times.17 DeWolfe’s video content, however, is often twisted and misinterpreted by his teen audience, who often write comments about how they now have “self-diagnosed ADHD” because they relate to some of the ADHD symptoms he depicts. The issue lies more with their interpretation than the quality of the information he is propagating. But, the fact remains that the misinformation and ADHD self-diagnoses in DeWolfe’s comment section remain unregulated, so he himself isn’t willing to reply to or delete misleading comments and risk losing out on valuable user interaction which will ultimately benefit his popularity on the app. Then again, he may be avoiding doing so because it may seem dismissive to rain on his commenters’ parades when they feel they are going through moments of self-discovery.

The question becomes, is it the responsibility of creators like De Wolfe to implement measures for reducing the misinterpretation of their videos, or is it the responsibility of these young viewers to refrain from trying to label themselves as disordered every time they encounter a relatable symptom of neurodivergence or mental illness? Where can the line be drawn? It’s difficult to settle upon a deterministic rule for this, especially since many teens who legitimately have undiagnosed mental disorders only pursue diagnoses and treatment after relating a bit too heavily to the video content about them.

On the other hand, in regard to the content creators who falsely co-opt and perform mental illnesses specifically to carve out a platform for themselves on TikTok (such as @theasystem), it may be a case of performative activism meets performative education meets misinformation. Research has shown that most TikTok activists and content creators begin with an admirable personal desire to contribute to public discourse on social issues.18 Some may later be motivated by the prospect of feeding their own egos by earning online validation through “virtue-signaling” — utilizing their mental health content as a means for demonstrating their own virtuousness to the internet masses — and by establishing themselves as a pseudo-clinical authority on a particular clinical topic. This two-fold social media-induced self-esteem boost is common among many users of the current major social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Reddit, etc.).19 20

Thus, when faced with either the prospect or potential loss of the app’s social currency of followers, likes, and views, many mental health “influencers” may choose to prioritize analytics over the quality and accuracy of the information they disseminate. You see, in order to go viral, educational TikTok content must be simply understood, convenient, socially engaging, and of high entertainment value.21 When faced with these constraints, creators may either purposely or inadvertently spread mental illness myths and misinformation, as influencers often do, regarding health conditions.22 Each neuropsychological illness on TikTok also occupies its own hashtag or algorithm built “side” of viewers—a bonafide echo chamber and optimal breeding ground for viral misinformation that may be so popular it gets interpreted as genuine fact.

For instance, again in the case of ADHD, because so many of its less debilitating symptoms can be misperceived as relatable quirks, its side of TikTok—with a following of 9.5 billion TikTok viewers and counting (fig. 1)—is littered with video creators, who, unlike Connor DeWolfe, are lay people without a clinical ADHD diagnosis. They encourage their audience to self-diagnose based on superficial characteristics and stereotypes of the disorder; oftentimes, the massively popular videos on this side of TikTok conflate symptoms of ADHD with neurotypical behaviors, practically synonymizing ADHD hyperfixations with typical passions and interests, falsely claiming fast talking and fidgeting behaviors are definitive signs of ADHD, and ignoring the fact that ADHD is a disability with numerous psychological comorbidities rather than, say, a quirky personality type.23 This can be especially damaging to those diagnosed with ADHD, like Fiona Devlin, a university sophomore at Texas A&M University, who feel their diseases are essentially being diluted in the public eye.

When interviewed by ADDitude Magazine, a publication that centers on the experience of living with ADHD, Devlin said of this widespread mischaracterization, “It can just be frustrating how everyone suddenly starts claiming they have something that they do not actually have. Then other people are like, ‘[ADHD is] not that bad…’ when in reality, if those things aren’t treated, it can be very harmful to your life.”24

The Consequences of Consumption

What about the consumers of this misinformation? Why are they so keen to consume and engage in these TikTok communities? Besides the fact that the content itself is designed to be easily consumed, it seems that mental illness’ revitalized appeal online may be related to TikTok users’ age group, along with the longstanding effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Depression and anxiety prevalence rates did increase significantly throughout the Covid-19 pandemic,25 which may account for the popularity of the #anxiety and #depressed hashtags (fig. 1). But the prevalence of many of these hashtagged disorders, such as ADHD, is historically low and did not significantly increase in the past two years.26 27 I surmise that there is indeed another mental health crisis at the moment, but not the one our TikTok data readily suggests.

Rather than a crisis of rare disorders coming into the limelight, it seems there is an ongoing crisis of identity in adolescents. Adolescence has been recognized as a time for constructing and developing one’s identity, higher-level social skills, and group affiliations. Yet, quite disastrously, the pandemic has rendered this a time of profound loneliness, isolation, and hence heightened depression and anxiety.28 The fragmentation, if not dissolution, of in-person communities and social gatherings in 2020 and 2021 has no doubt exacerbated adolescents’ yearning for establishing, participating in, and belonging to online social communities. Even now, in-person communities remain in a state of recovery, leading adolescents and young adults to define themselves by any community, and labels and affiliations they can grab onto—regardless of the implications or scientific soundness of affiliations. For some, this may lead to gravitating towards and situating their identities in mental illness.

Testimonials, tidbits, and POVs from mental health gurus and self-proclaimed mentally ill individuals on TikTok may romanticize and glamorize mental illness, transforming medical labels into social identifiers that these adolescents accept without realizing their gravity. They may not have the knowledge base, or sometimes the skills, to differentiate between what’s accurate and what has been concocted for views. Many of these teens are ripe to take what TikTok’s assortment of confident, articulate and publicly-endorsed gurus says at face value. After all, their content is far easier to understand and accept than the medical jargon that litters clinical research articles and psychiatric manuals. The problem arises when these teens so strongly identify with mental illness-focused communities that they convince themselves they too are ill. What does it matter if you have multiple personalities, as long as you have a home to call yours? They go from passive consumers to soon considering themselves members of a side of TikTok that surrounds mental illness; as they yearn to be more involved in their “side,” they fall victim to the shroud of illness around them, developing sociogenic tics, suffering from persistent low mood, or creating so-called alters to feel like they too have a place in the community.

In the case of dissociative identity disorder (DID), it’s not surprising that teens on the #DID side of TikTok are defining themselves by the fact that they have fragmented selves, as they are still forming their complete identities. Still, it is problematic when the #DID video creators frame the typical psychological development of the adolescent and young adult age groups as symptomatic of a serious, debilitating mental disorder. For one thing, it, much like the ADHD-focused TikTok content, dilutes the seriousness of the disorder. It also reflects the fact that when adolescents develop their personal identities, they’re often driven by a desire to define themselves against the norm, avoiding similarity to others as a way of establishing their own uniqueness as an individual.29

TikTok teens’ tendency to define their individuality through claims of mental illness or neurodivergence resembles past teens’ involvement in various internet-based and in-person subcultures.30 In a sense, being neurologically and/or psychologically atypical has become a subculture of its own on TikTok, occupying distinct sides in which community members can position themselves against the norm of neurotypicality. Thus, the original meanings of these terms—”neurodivergent” and “mentally ill”—have become utterly lost in online landscapes.

A Final Word for the Youth

mental illness noun

variants: or mental disorder or less commonly mental disease

Definition of mental illness

: any of a broad range of medical conditions (such as major depression, schizophrenia, obsessive compulsive disorder, or panic disorder) that are marked primarily by sufficient disorganization of personality, mind, or emotions to impair normal psychological functioning and cause marked distress or disability and that are typically associated with a disruption in normal thinking, feeling, mood, behavior, interpersonal interactions, or daily functioning31

In short, a disorder, fundamentally, is a hindrance to daily life. If it needs any reiteration, a person clinically diagnosed with dissociative identity disorder is ill; their cognitive and social functioning is impaired; they cannot twiddle their thumbs in front of their iPhone and switch personalities on command to delight the masses on TikTok. As much as I’m thrilled certain mental illnesses are being destigmatized on the internet, I must stress that there lies a difference between accepting differences in neurological/psychological functioning and masquerading around as mentally disordered individuals for the purpose of identity formation.

Truly, I am imploring for this to end. If we now neglect to intervene in these communities of adolescent creators who are romanticizing mental illness in the midst of finding themselves, if we resign to cast them off as misguided or dramatic and move on with our lives, just as did to the ex-Tumblr teens, we’re essentially resigning to the possibility that this will happen as a phase for every generation that gets ahold of the internet communities. This isn’t a novel or surprising phenomenon. It’s one that has occupied a stronghold since the dawn of social media. It comes in waves — the Tumblr teens figured out that anorexia and suicide aren’t beautiful towards the latter half of the last decade. For a while, romanticized mental illness fell into obscurity. Generation Z, with our youth and optimism, thought ourselves better than the Millennials who had been struck into depression as the first generation to be worse off than their parents. But we’ve fallen victim to the same issue in a different form. Will we have to wait until at least 2025 for ADHD, DID, and Tourette’s to no longer be trendy? Will the young adults in 2030 still be grappling with the after effects of false tics and “alters” that they never united into genuine selves, which may affect their prospects in the job market and leave them wondering who they really are deep into their thirties?

I don’t know what the optimal interventional strategy should be. I’m opposed to censorship (within reason), so completely eliminating this kind of content is out of the question. But, I refuse to accept that we ought to simply wait out the trend, especially as it can have devastating psychological consequences. Perhaps, the solution lies in rapidly educating adolescents about the possible consequences of engaging in these communities—the dangers and the benefits. The most efficacious method for this might be directly through social media itself—whether this be through TikTok video series, various disclaimers in TikTok video descriptions, informational posts on social media like Instagram, which are highly linked to TikTok in public discourse, or other platforms.

I myself tend to shy away from social media for non-research or content consumption purposes, so I suppose I’ll use the digital space I have here to leave my own cautionary message for the youth who have rooted their identities too deeply in their own mental strife:

I do empathize with your plight. The need for social bonding pervades across every generation, and, seemingly, so does a desire to define oneself against the norm. But, I worry for you all. To me, you are just children whose lives have become deeply entwined with a community that rides on the concept of solidarity in shared illness.

It’s perfectly okay to have a mental illness, or to be neurodivergent. That being said, don’t purposely define yourself by that one aspect of mind or brain even if it means finding a like-minded community. That goes for all aspects of life—you are, in fact, multi-faceted.

For those who haven’t been diagnosed but feel deeply aligned with a mental illness or syndrome, please seek out a licensed professional immediately. TikTok may be the beginning of your mental health journey, yet it cannot be the only space where this journey takes place. You alone, regardless of your TikTok community affiliations, may not be at the point to decide who you are or self-evaluate your own mental state. Just because you can’t make eye contact with people anymore and feel uncomfortable in the world your peers seem to inhabit so well, doesn’t mean you have autism spectrum disorder. You’re not necessarily dissociating because you zone out or haven’t quite formed your identity in the transition between childhood and adulthood. Yes, indeed, maybe it’s anxiety, maybe it’s autism, maybe it’s dissociation, maybe you just don’t vibe with anyone around you—the fact of the matter is, TikTok won’t be able to tell you for certain or assuage all your fears.

But, these TikTok communities’ propensity for self labeling which then becomes self-diagnosing can have devastating effects on you, even after you mature and leave. You’ll get too comfortable there and be stuck in an echo chamber—a community where you’ll feel like this strange, anxious, uncertain state of mind is normal and all it’s ever going to be. You’ll find a home in that community, which is defined by mental illness, and end up convincing yourself that it’s okay to stay in that same ill state. That will be your comfort zone forever. You’ll miss out on all the growth you could’ve had because you convinced yourself that it was normal to stay disordered. It’s not normal, and it can be overcome. You don’t need to sacrifice your growth just to feel accepted and related to. You’ll outgrow this. I know you will if you try.

If you’ve skimmed over the last few pages and digested none of them, I only ask that you heed this. As a person who has observed the profound extent of loss and dysfunction that clinically-diagnosed neuropsychological conditions—including TikTok’s beloved ADHD and the less-than-popular schizophrenia—can bring to a person and their loved ones, I wouldn’t wish them upon anyone. They can be true devastation. Mental illness is a world you don’t want to fit yourself in.

To teens and young adults who may be swayed into joining these communities for the purpose of finding themselves, or attaining an online claim to fame, I urge you, sincerely, find an identity in something else. This is not one to try on for size.

- Brian Dean, “Tiktok User Statistics (2022),” Backlinko, Semrush Inc, last modified January 5, 2022.

- Guilherme Polanczyk et al., “The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis,” American Journal of Psychiatry 164, no. 6 (2007): 942-948.

- Roger D. Freeman et al., “An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3500 individuals in 22 countries,” Developmental medicine and child neurology 42, no. 7 (2000): 436-447.

- World Health Organization, Depression and other common mental disorders: global health estimates, No. WHO/MSD/MER/2017.2, World Health Organization, 2017.

- Mayada Elsabbagh, Gauri Divan, Yun‐Joo Koh, Young Shin Kim, Shuaib Kauchali, Carlos Marcín, Cecilia Montiel‐Nava et al., “Global prevalence of autism and other pervasive developmental disorders.” Autism research 5, no. 3 (2012): 160-179.

- Daniel Vigo, “The health crisis of mental health stigma,” The Lancet 387, no. 10023 (2016): 1027.

- Roger D. Freeman et al., “An international perspective on Tourette syndrome: selected findings from 3500 individuals in 22 countries,” Developmental medicine and child neurology 42, no. 7 (2000): 436-447.

- Joanna H. Cox et al., “Social stigma and self-perception in adolescents with tourette syndrome,” Adolescent health, medicine and therapeutics 10 (2019): 75.

- Olvera, Caroline, Glenn T. Stebbins, Christopher G. Goetz, and Katie Kompoliti. “ TikTok tics: a pandemic within a pandemic.” Movement Disorders Clinical Practice 8, no. 8 (2021): 1200-1205.

- Tamara Pringsheim et al., “Rapid onset functional tic‐like behaviors in young females during the COVID‐19 pandemic,” Movement Disorders (2021).

- Dawn Beverley Branley and Judith Covey, “Is exposure to online content depicting risky behavior related to viewers’ own risky behavior offline?,” Computers in Human Behavior 75 (2017): 283-287.

- Anima Shrestha, “Echo: The Romanticization of Mental Illness on Tumblr,” The Undergraduate Research Journal of Psychology at UCLA (2018): 69-80.

- Munmun De Choudhury, “Anorexia on tumblr: A characterization study,” In Proceedings of the 5th international conference on digital health 2015, pp. 43-50. 2015.

- Patricia A. Adler and Peter Adler. “The cyber worlds of self‐injurers: deviant communities, relationships, and selves.” Symbolic interaction 31, no. 1 (2008): 33-56.

- Rachel Premack, “Tumblr’s Depression Connection,” The Ringer, The Ringer, October 24, 2016.

- Young‐Mee Kim and Sung‐il Cho, “Socioeconomic status, work‐life conflict, and mental health,” American Journal of Industrial Medicine 63, no. 8 (2020): 703-712.

- American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

- Daniel Le Compte and Daniel Klug, ” ‘It’s Viral!’ – A study of the behaviors, practices, and motivations of TikTok Social Activists,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2106.08813 (2021)

- Rebecca A. Hayes, Caleb T. Carr, and Donghee Yvette Wohn, “One click, many meanings: Interpreting paralinguistic digital affordances in social media,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 60, no. 1 (2016): 171-187.

- Elaine Wallace, Isabel Buil, and Leslie De Chernatony, “Consuming good on social media: What can conspicuous virtue signalling on Facebook tell us about prosocial and unethical intentions?,” Journal of Business Ethics 162, no. 3 (2020): 577-592.

- Johannes Ahlse, Felix Nilsson, and Nina Sandström, “It’s time to TikTok: Exploring Generation Z’s motivations to participate in #Challenges,” (2020).

- Chris Rojek and Stephanie A. Baker, Lifestyle gurus: Constructing authority and influence online, John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Camille Williams, “TikTok Is My Therapist: The Dangers and Promise of Viral #Mentalhealth Videos,” ADDitude, WebMD LLC, January 7, 2022.

- Camille Williams, “TikTok Is My Therapist: The Dangers and Promise of Viral #Mentalhealth Videos,” ADDitude, WebMD LLC, January 7, 2022.

- Maddy Reinert, Danielle Fritze and Theresa Nguyen, “The State of Mental Health in America 2022,” Mental Health America, Alexandria VA, October 2021.

- “Data and Statistics about ADHD,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, September 23, 2021.

- “General Prevalence of ADHD,” Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD), September 25, 2020.

- Robert L. Cloutier and Rebecca Marshaall, “A dangerous pandemic pair: Covid19 and adolescent mental health emergencies,” The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 46 (2021): 776.

- Charles R. Snyder and Howard L. Fromkin, “Abnormality as a positive characteristic: The development and validation of a scale measuring need for uniqueness,” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 86, no. 5 (1977): 518.

- Sarah Hanks, “Selling Subculture: An examination of Hot Topic,” Kinderculture: The corporate construction of childhood (2011): 93-114.

- Merriam Webster Online, s.v. “Mental Illness,” accessed March 20, 2022.