Mosaic uses its platform not as a misguided appeal to younger audiences, but as a conceptual way of exploring the thematic idea at the core of the show.

Building a Mosaic

What if I told you that someone released a TV show through a choose-your-own-adventure-style interactive mobile app? If you’re like me, your mind would probably conjure the image of a room full of middle-aged entertainment executives, desperately trying to figure out what the kids are into nowadays and how they can turn that into ratings. Yet, what I was greeted with while interacting with HBO’s Mosaic was a product that uses the platform not as a misguided appeal to younger audiences, but as a conceptual way of exploring the thematic idea at the core of the show.

Mosaic is a collaboration between filmmaker Steven Soderbergh and HBO, and, in many ways, it is the culmination of a series of long-term shifts in the entertainment industry. Soderbergh and the team that built the platform seem to have recognized that television is a medium in which the story that is being told is defined more and more by the audience’s entertainment consumption habits. The medium, which used to be little more than a vehicle for advertisements, has now been optimized for a generation of binge-watching smartphone users looking to consume how they want, when they want. The organization of the app and the particular way in which the story is allowed to unfold is replete with clever ways of utilizing and exploiting these changing habits.

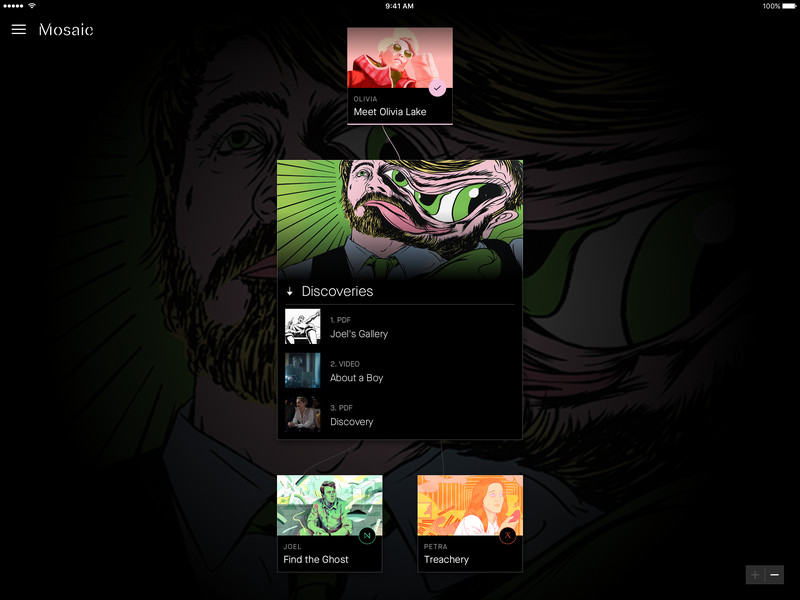

The layout of the app is rather bare, consisting only of a black background on which is displayed a network of episodes branching off of one another. After watching the first episode—a twenty-four-minute flashback taking place four years before the events of the show—the user unlocks the following two and is granted the opportunity to choose which narrative avenue they wish to pursue. From that point on, the narrative can be explored as desired. One can watch new episodes to unlock different sides of the story or return to episodes previously unlocked that haven’t been watched yet. “Discoveries” such as documents, newspaper articles, or scenes that provide additional context also become available as the user continues to progress through the app. There is a larger world surrounding the story than simply what is being shown to us, a world that the viewer is in charge of piecing together.

Although these features ultimately serve the purpose of enriching the viewing experience, they nevertheless employ techniques that reflect the distinct possibilities of mobile applications. In forcing viewers to unlock episodes instead of allowing total access, Soderbergh and his team are creating a desire to unlock the entire map, not only in order to continue the story, but also in order to receive the satisfaction of unlocking it, as would someone trying to do the same in a game such as Candy Crush. Furthermore, the discoveries that are periodically released add a sense that every new episode holds the possibility of delivering supplementary rewards, much in the same way that other apps attempt to mirror the reward-based structure of slot machines. What this creates is a compulsion to engage with the app that isn’t confined to the story being told.

Beyond the elements of the platform, the content of the show also exploits this new medium in order to tell a conventional story in an unconventional way. The basic plot of the show revolves around the murder of Olivia Lake, a once-famous children’s author and founder of a non-profit called Mosaic. Lake’s one publishing success, Whose Woods These Are, tells of an encounter between a bear and a hunter in which the experiences of both are depicted as if they were each the protagonists. The hunter is trying to protect his family from the bear just as the bear is trying to do the same with its family. Both of these characters exist as the heroes of their respective stories and the villains in the others’. This idea is reflected in the larger organization of the show.

Each of the episodes depicts the events more or less from the perspective of a single character. This allows the viewer to understand these characters in a way that would’ve been more difficult had they been treated as secondary aspects of someone else’s story-line. When the audience is offered the opportunity to choose the next episode to watch, their decision involves deciding whether or not to keep watching the events unfold from this one perspective, or to view it from another. As Nate Henry, the detective in charge of finding Olivia’s killer puts it “the choices you make, the sides you pick. They have consequences.” The variable at play here is the order in which information is revealed to the audience. Depending on this order, the viewer can come to radically different interpretations of the significance of given scenes, and even of the nature of each character. The audience will often be presented with the same scene told from two different perspectives (and edited to reflect this) at completely different times in their respective stories. In one instance, the viewer might believe that a character’s motivations are genuine only to later find out that they were being duplicitous.

This takes the typically passive act of watching a TV show and turns it into an active one. In Mosaic, the viewer is many things, including a detective. This is a show that will make you want to stay up late reading fifteen-page PDF documents trying to find clues. But perhaps above all the viewer is an artist, the creator of their very own mosaic, trying to piece together the truth of this murder from the perspectives of these different characters. The experience of the show doesn’t take place on the screen, it exists in the viewer’s mind–in the collective viewer’s mind.

Therein lies the show’s real innovation. In allowing the viewer the opportunity to define their own experience with the show, Soderbergh and his team have created an opportunity for everyone to encounter a different version of the work, one that makes them empathize with some characters and not other. The mosaic that lends its name to the show isn’t simply Lake’s non-profit, nor is it the evidence that the detectives (both inside and outside the show) attempt to shape into a neat, cohesive image. Rather, it’s the fractured and diverse tapestry of viewing experience that the filmmakers have substituted for the monolith of experience typical television provides.