”In search of a bride for their son, elderly women “sometimes look for tall, blonde and white women. You find this not only in Jordan, but also in Syria and in Iraq,” Hijazi says.

Nose Jobs and Neo-Colonialism

Beauty Trends in the Arab World

“The Caucasian nose has always been the gold standard,” says Jordan-based plastic surgeon TK.

*interviewees have requested to remain anonymous – different names have been selected for them.

Growing up, Dina, a twenty-three-year-old Jordanian-Palestinian, craved and sought out images of noses she saw amongst celebrities and on social media. To her, Kendall Jenner and Madison Beer had the perfect noses she itched for. “I would show my mom their pictures, telling her that this is what I wanted my nose to look like post-rhinoplasty,” she recalls.

Why would Dina want a different nose than the one she was born with? “My nose was always compared to my grandma’s large Arab nose and I was always made to feel that this was a bad thing,” says Dina. Her upbringing in Amman, Jordan had conditioned her to normalize rhinoplasties, as many young and older girls around her underwent the surgery in search of a “perfect” nose. “There was a time when every single girl in my class in high school was getting her nose done before graduation,” she says.

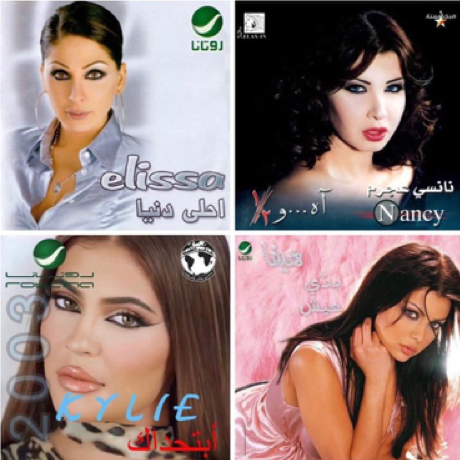

Arabic popular culture icons such as Elissa, Nancy Ajram, and Haifa Wehbe have reinforced a distinctive image of an ideal nose. Their reconfigured noses seem to be clone copies of one another: small, straight and uplifted—the Caucasian nose.

In a world where Caucasian facial features constitute the ideal beauty standard, it’s no wonder that Arab women have attempted to fulfill this standard through surgery. Physical appearance is a prominent identifier of one’s heritage. In an article published by Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open, experts said that the popularity of ethnically ambiguous and Caucasian-seeming features could mean that an Arab ethnic identity could become lost in translation amongst the chaos of globalization.

Research into the popularity of rhinoplasties highlights that rhinoplasties were among the top five most popular procedures worldwide. The Middle East, in particular, has always been a hub for rhinoplasties due to its reasonable prices and popularity. A 2018 survey conducted by Tajmeeli, a Middle East-based cosmetic surgery writing website says that rhinoplasties were the second most requested cosmetic surgery.

Plastic surgery in the Middle East has always been popular. Dr. TK, a Jordan-based cosmetic, plastic and reconstructive surgeon says plastic surgeries in the Middle East, including Iran and Turkey, are increasing in number. Inevitably the numbers of rhinoplasties are also rising. “It’s a steady and stable increase,” he says. Globalization and increased exposure to Western beauty trends and popular culture may have contributed to Arab women’s decisions to undergo surgery. Simultaneously, an increased awareness of global dynamics may have led Arab women to realize the weight of the constant pressure imposed on them to look a certain way – including Dina.

Literature addressing standards of beauty across the Middle East is relatively scarce, particularly because the region contains a wide range of ethnic and racial diversity. In a 2019 study carried out by 17 dermatologists and plastic surgeons from across the Middle East, aspirational differences in plastic surgery were found between the Middle East and the West, and also within the Middle East, with Arabian (UAE and Saudi), Levantine (Lebanon and Jordan), Iranian, and Egyptian being the sub-categories analyzed in the study. This implies that it is not so easy to conclude a causational relationship between Westernization and beauty standards in the Arab world. Limited knowledge into the aesthetic inclinations and facial anthropometry of Arab women could result in the imposition of Western beauty without acknowledging culturally recognized or identified facial characteristics.

Women in Dr. TK’s clinic often show images of celebrities before undergoing nose surgery. Right now, images of Gigi and Bella Hadid are common in his workspace, but celebrities are constantly changing. “When I first started, it was Jennifer Lopez,” says Dr. TK. “Now because Turkish soap operas are everywhere, I get Turkish and Lebanese actresses.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, Arab women paid little attention to achieving a “natural” look with plastic surgery. “Actresses and celebrities wanted their noses to be as Caucasian as possible,” Dr. TK says. This same group of women traveled to Lebanon to the same group of surgeons, achieving the same nose. Now, however, “the trend is based on a natural, preservational look” explains Dr. TK.

The popularity and cultural acceptance of Hollywood in the Middle East in the 20th century and today results in the exposure of Arabs to Western and Eurocentric beauty standards in television, including a Caucasian nose. “Arab television between the 70s and 90s was mostly American. Now, we have Bollywood, celebrities from Asia – from South Korea. Globalization is happening. Things are changing. But thirty to forty years ago, it was all white people on TV,” says Dr. TK.

“Global” Arab cities such as Dubai have a higher concentration of cosmetic clinics than Hollywood, according to a study. The idea of “global” Arab cities that are home to international citizens could explain the prevalence of ethnically ambiguous features as a new ideal beauty standard.

Ethnically ambiguous features amongst women in television and social media, including Kylie Jenner, could mean that it is difficult to draw the line between whether Arab women remain affected by Caucasian beauty ideals. Perhaps women’s reclamation of Caucasian features as their own in a new preservational rhinoplasty trend is an indicator of reclaiming bodily autonomy.

Hala Hijazi, a 52-year-old Iraqi-Jordanian woman living in Jordan underwent two rhinoplasties at an uncommon age for the surgery—her thirties. To her, beauty standards in the Arab world are constantly shifting, “but the nose has always been seen as better if it is small.”

“Self-confidence was never built into our upbringing,” says Hijazi. Plastic surgery, therefore, can be seen as a quick fix for deeply rooted self-esteem issues amongst women. “We care so much about what others think of us,” Hijazi explains. “An issue prevalent in all societies, but specifically Arab ones.” Hence, certain Arab beauty figures idolize the small, narrow Caucasian nose.

Dr. TK learnt from medical textbooks he studied during his years at university that “the Caucasian nose has always been the gold standard.” What constitutes an ideal nose is symmetry and harmony. “No one has a symmetrical face. The more symmetry you have, the more attractive you are,” he says. Harmony involves how the features of the face function in relation with each other.

Sections of older medical textbooks address ethnic Asian, Middle Eastern and African noses “to basically turn them into Caucasian noses,” Dr. TK explains, since Caucasian features supposedly inhere the most harmony and symmetry. “In my experience, a perfect nose is one that is harmonious with the face. It’s not necessarily one that is a text-book nose,” says Dr. TK.

Dina, Hijazi and Dr. TK all acknowledge that older Arab women – particularly in their 60s and 70s seem to have a liking towards Caucasian women and specific features. “I see it in my mom and my aunts,” explains Hijazi. “When they see someone who has Caucasian features, attractive or not, they say that she’s really pretty.” In search of a bride for their son, elderly women “sometimes look for tall, blonde and white women. You find this not only in Jordan, but also in Syria and in Iraq,” Hijazi says.

According to a journal published by Harvard University’s International Socioeconomics Laboratory, European colonization can very well be attributed to the beauty standards across the Middle East. “White people have dominated the world with their empires, technology, armies. And so, they’re attractive in many ways because of how they’ve dominated the world,” Dr. TK suggests.

Dina, an alumnus at New York University Abu Dhabi, began to reflect about colonialism and orientalism in the Middle East and how they impacted her individually and intergenerationally before and after her surgery. Initially, she thought her decision to undergo surgery stemmed from insecurity, and that it would enable her to love herself. “It didn’t entirely help. I was still feeling insecure after and questioned why it didn’t solve my problems,” she says. Her exposure to post-colonial studies in college enabled her to view her surgery in a different light—through an Orientalist concept of “othering.”

The body is central to the concept of the “other.” It seems that Arabs are antagonized based on their features. “I was made to feel my features and nose looked wrong, because my society also followed these trends. We’re brainwashed and have internalized these ideas,” Dina says. Labeling her grandmother’s nose as an Arab one reinforces the notion that having an Arab-looking nose is considered undesirable or unattractive.

Andrew Ragni, PhD, a teaching fellow at New York University in the department of comparative literature explains the intertwining of colonialism and the body through psychoanalysis. “There’s always a running construction happening that the colonized must be like the colonizer in some way in order to be legible as the lowest form of subjectivity allotted to them, but they also must always be different in a striking way,” he explains.

When it comes to beauty standards in particular, the face of the colonized or “exotic” woman is usually written about in such a way that when it becomes exceptionally beautiful, “she becomes like a Western woman, or good enough to be like a Western woman,” says Ragni. Consequently, an unattainable ideal and norm is imposed on the rest of the women. If a non-white woman approximates the beauty of a white woman, “this offends the entire ideology around white supremacy.” Therefore, she must always approximate, “but never quite arrive at the ideal itself,” keeping up the status quo, says Ragni.

It seems that while colonialism in the Middle East is in the past, neo-colonialism has manifested itself in these cultural trends. The effects of globalization, Westernization, popular culture and social media blur the lines between Arab women’s redefinition of beauty and the harmful impacts of a Western hegemonic gaze on Arab society.

Ethnically ambiguous features have resulted in the “Arab” Kylie Jenner meme, in which Jenner comically resembles Arab pop-stars like Haifa Wehbe and Ahlam in her recent beauty campaign. Are women in the West trying to look more like Arab women? Or are they trying to resemble Arab women’s attempts at looking more white? Should we, as Arab women, feel empowered by our trending features? Or are our trending features making it difficult for us to unravel the imprints of colonialism on our body politics?

Dina has taken a stance against neo-colonialism, Colonialism and Orientalism by not conforming to these beauty standards. She suggests “embracing what we have and showing that there isn’t one set way to look.”

For Hijazi, after two surgeries, she is still somewhat unsatisfied. “But you have to accept and love yourself. You’ll never be happy if you don’t,” she says.

The scope of this article doesn’t allow me to delve completely into the historical and cultural dynamics at play. Refer to the following articles for further information:

Campaign Staff. “Perceptions of beauty in the Arab world – Campaign Middle East.” Campaign Middle East. 17 Nov. 2013. Web. 27 Nov. 2023. <https://campaignme.com/perceptions-of-beauty-in-the-arab-world/>

Chen, Toby et al. Occidentalisation of Beauty Standards: Eurocentrism in Asia. Zenodo, Dec. 2020, doi:10.5281/zenodo.4325856.

Hashempour, Parisa. “Middle Eastern looks are ‘trending’, but where does that leave Middle Eastern women? – gal-dem.” Gal-dem.com. n.d. Web. 27 Nov. 2023. <https://gal- dem.com/middle-eastern-beauty-trend/>

Guillen Fabi, Sabrina. “Aesthetic considerations for treating the Middle Eastern patient: Thriving in Diversity international roundtable series.” Wiley Online Library. 6 Feb. 2023. Web. 27 Nov. 2023. <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jocd.15640>

Kashmar, Mohamad. “Consensus Opinions on Facial Beauty and Implications for Aesthetic Treatment in Middle Eastern Women.” PubMed Central (PMC). Wolters Kluwer Health, Apr. 2019. Web. 27 Nov. 2023. <https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6554175/>