Sergio Larrain’s

Photography as a Way

. . . of Connecting to the World

“We have grown accustomed to thinking of the camera as an aggressive device: an instrument for shooting, capturing, and representing the world. Since most cameras require an operator, and it is usually a human hand that picks up the apparatus, points it in a particular direction, makes the necessary technical adjustments, and clicks the camera button, we often transfer this power to our look.”—Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy

“I prowled the streets all day, feeling very strung-up and ready to pounce, determined to “trap” life—to preserve life in the act of living. Above all, I craved to seize, in the confines of one single photograph, the whole essence of some situation that was in the process of unrolling itself before my eyes.”—Henri Cartier-Bresson, “The Decisive Moment”

I

Indeed, it is common to regard the camera as an aggressive device; the words “to shoot” and “to capture,” which, two centuries ago, were probably not used much outside a handful of certain occupations—hunters, fishermen, police, villains—today find themselves predominantly uttered by photographers and cinematographers and in the context of photography and film. An associative link remains—the photographer is often associated with a hunter—he hunts moments and captures them into photographs. He is a conqueror: He conquers life and brings back visual testimony. And even when he isn’t going after his pictures aggressively, the photographer is often an intruder because he is a stranger to those he photographs, an outsider to where he photographs, and therefore he is a threat. The photographer is a voyeur: he looks at what may not want to be seen.

One such example—of an aggressive and voyeuristic photographer—we find in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up (1966)—probably the most famous film about a photographer. Thomas is a fashion photographer based in London in the late 1960s; he drives a Rolls Royce convertible, arrives at his photo sessions when he wants, gives orders to his models in a manner of an army commander, and wields his camera frantically. There is a scene with him having a photoshoot with a pretty model in a skimpy dress; it ends with Thomas yelling “Yes, yes, yes!” as he is getting the shots he wants, sitting mounted on top of the model who lies prostrate on the floor.

Blow-Up gives us a depiction of the photographer as a macho figure, a women seducer, a capturer, an extractor of beauty and style. The plot of the movie hinges on a short voyeuristic episode in a park, where Thomas furtively photographs a couple—he might have accidentally captured a murder. Blow-Up is fiction, however, exaggerated as the photographer figure it offers is, it isn’t that far from reality (Thomas’ character was inspired by the British photographer David Bailey). The fashion photographer in the UK in the 1960s (the Swinging Sixties) was a mythical and powerful figure; in the movie, two young women are quite desperate to be photographed by Thomas. Some fashion photographers have lived in a manner similar to Thomas’, and the lifestyle is still appealing.

*

There are photographs where we perceive that the taking of the photograph was a somewhat aggressive act. Bruce Gilden’s (b. 1946) New York City street photographs of people, often shot from a very close distance and using a flash, are such photographs.

In 2008, WNYC produced a video showing Gilden at work, roaming the streets of midtown Manhattan, jumping in front of people and setting off his flash. Gilden’s earlier street work was quite a bold and intrusive way of taking photographs; many think his approach was rude and the pictures don’t deserve to be called art. I disagree. I doubt anyone got seriously traumatized or hurt by Gilden taking a photograph of them. And the result—some of the photographs he’s left behind—are gorgeous. True, the faces and poses of the people photographed may look a little artificial because of the unexpected flash. Some will say Gilden has made the people he’s photographed look awkward and ugly. But sometimes awkward is elegant and ugly—beautiful. I think there is something very real in the expressions and bodies seen in Gilden’s street photographs, and it’s not just because of the flash. Intrusively taken—and therefore offering scenes that are produced, not so much recorded—as these photographs may be, the moments and people in Gilden’s photographs look sincere. And sincerity is something you access rather than create. In Gilden’s case, he accessed sincerity by actively seeking it rather than by passively observing. These photographs had to be taken in an aggressive manner. A nonintrusive, more amicable approach—the kind of street photography that might be said to show the romantic side of life, to celebrate the life in the street (the kind of street photography that the public likes and that makes them regard Gilden’s kind of photographs as dubious at best)—may not have revealed something significant about these late-twentieth-century Manhattanites. Without Gilden, maybe nobody would have photographed them at all. I’m glad his photographs exist—they are both a record of the unique and vibrant people of Manhattan (from time when screens were for off the street and when people wore shoes not sneakers), as well as a strong visual testimony showing what being a human can look like universally. (All photographs of a person show simultaneously the particularity of that person as well as something more universal about being human, but the really good photographs, bodies of work, show aspects about being human which no other photographs have or other mediums can.)

Theoretical Excursus

There are photographs that show such striking (or perfect or poignant or beautiful or funny or absurd or tragic) moments that instead of saying “photographed,” we frequently opt for the more aggressive “captured”—What a moment has the photographer (or the camera) captured!

It can be the moment or the thing photographed (the subject matter) itself that all these adjectives describe. How technically or compositionally well taken the photograph is doesn’t particularly matter. For example, a poor quality phone camera photograph of a squirrel carrying a slice of pizza up a tree is still going to make us say, What a funny moment!, despite the photo being blurry or awkwardly composed. Or, a photograph of a kitten sitting in a wet cardboard box on the side of the road is probably going to arouse emotion in us, even if the photograph is not exposed correctly, i.e., it is too dark or too bright.

Of course, there are technically and compositionally excellent photographs taken of excellent moments. In these cases we still usually talk about the moment, the fragment of life, that the photograph shows. Just like in the previous case, the photograph as an object recedes; we may even forget that we’re looking at a photograph. Here, the photograph is a window on reality. Take as an example a high-quality photograph of mountain scenery, taken in beautiful light conditions—Apple computers usually have such photographs as their pre-loaded desktop background. The moment, the view that the photographer saw before taking the photograph, was beautiful (it must have felt so). But we can also step back and appreciate that it’s photographed well—that the view that we can see now is beautiful. What beautiful mountains!, some will say; What a beautiful photograph of mountains! will exclaim others.

And then there are photographs which are beautiful or striking or which have a quality about them that makes us pause and look, however, before they were taken, the world around where they soon would be taken didn’t seem too conducive for such a photograph to happen. Nothing much was happening in the world where the photographer was standing. Nothing seemed of particular interest, general or aesthetic. Or, quite the opposite, so much was happening around that it seemed very difficult to take a photograph that would not be cluttered. And yet the photographer saw, or sensed, something and took a photograph. Or maybe he knew or sensed that the place was right but that he had to wait a little, wait for the elements to rearrange and fit in the right places or wait for something new to enter the scene, and the photograph would be there. Now, when we look at that photograph, we feel that it’s a good photograph. It may be the perfect moment captured, or the mood, the effect of the shapes, the geometry in the photo, or it can feel like the photograph is a glimpse of something higher, of eternity maybe. Whatever it is that makes this photograph more special than others, it probably wasn’t that easy to take it as the moment was unfolding in real time. But the photographer did. The photographer either hit the perfect moment or noticed some quality or truth in what to most would seem only a mundane moment in a mundane scene; and he clicked the shutter. What we now see between the four edges of the rectangle is beautiful, is art. We can say, What a beautiful moment photographed, however with this type of photograph, it is the photographer who has the most merit. The world wasn’t showing easily what the photograph conveys—one had to look carefully, align themselves with the moment, probably be practiced in looking at the world in a certain way.

This latter kind of photography—the photographer against, or at play with, a world that does not have good photographs lying on every corner—is what good photography for the most part consists of. Of course, sometimes moments happen and all we have to do is pull out our camera; or we know what scenery or object or person looks good, we just need good equipment to take quality photographs. But for the most part, it is a quest, if not sometimes a struggle, to get a good photograph. Something is always available, but the good stuff takes effort and time. Just like in other domains of life—effort and time are needed to achieve a good result.

But we have been talking here as if the world comes first, and then it gets photographed. That’s logical. But we should also note that photographs create1 new worlds. Photography’s material is the visible world, but it can do more than just copy it. By transferring a piece of the world to a rectangle, the photograph has opened up a new world within the existing one. And while the world moves on, the photograph remains—it becomes a world of its own.

But going back to language: there are photographs, and there are captures. It is usually by the ability to deliver the latter, to deliver “captures” constantly, that we judge if someone is a good photographer.

Part I continues

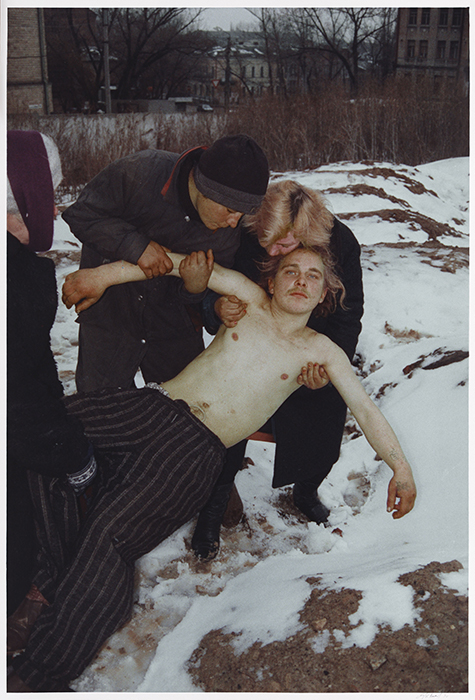

There are photographs, looking at which, we may ask, Did what has been photographed want to be photographed? The pretty girl on Instagram wanted to be photographed with her deep décolleté; she wanted that photograph to reach a large audience. But did, for example, the homeless people in Boris Mikhailov’s (b. 1938) photographs want their miserable life to be transformed into art?

Quite possibly they didn’t mind—or wouldn’t mind if they knew that their images are now world-famous. Boris Mikhailov’s Case History (1997–1998) is a body of work showing the everyday life of poor and homeless people in post-Soviet Ukraine. Homeless people emerged in Ukraine after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. The images are stark, they show deep poverty and, for the most part, misery.2 Since Mikhailov is more or less a stranger to his subjects—and on several occasions he has made them pose naked—there arises the question of how the photographs are used. These were exhibited at world-class institutions and are printed in catalogues and books. The art world appreciated this body of work; but maybe there is someone out there now who is featured in Mikhailov’s book and is rather ashamed that people all over the world can see them in an unflattering photograph. On the other hand, the same reading as to Gilden’s work applies—Mikhailov’s photographs show what being a human can look like. Is it weakness of spirit or the consequences of a shabby political system turned into a greedy one?

The camera can be used to obtain trophies; a photograph can function as a trophy—I was here, I did this, I met this person, etc. Carlo Mollino (1905–1973) was an Italian designer and architect, and engineer; he was also a downhill skier and a stunt plane pilot. Yet despite his active engagement with the world, Mollino remained a mysterious, reclusive man. He had an apartment/villa in Turin of which nobody knew; now a museum, it is exquisitely furnished and houses many beautiful and curious objects. Mollino perfected the house for 13 years, until his death. The house was the ultimate expression of Mollino’s taste, but it was also something more—it was a shrine for his being. Interested in the ancient Egyptian culture, Mollino had arranged the apartment to resemble a Pharaoh’s tomb. In one room, there is a boat-shaped bed, for the ancient Egyptians believed that that’s how you travel to afterlife.

One of Mollino’s secretive activities in the villa was taking erotic photographs of women. These were found only after his death. Carlo Mollino: Polaroids (Damiani/Crump 2014) contains several hundred Polaroids of women, dressed in erotic outfits, or somewhat dressed, or not dressed at all, taken by Carlo Mollino in his Turin villa. They are staged photographs, where the background, clothing and accessories were curated by Mollino. The poses are staged too, yet the women mostly look comfortable and natural.

Mollino’s intentions with this body of work are unclear, but one can possibly interpret the collection as saying: I possessed these women, here are their photographs. Although probably nothing more than photography happened between Mollino and his models, since he allegedly never spent the night in the villa. That’s also probably not the right interpretation, because the feminine form is present throughout Mollino’s design works; the Polaroids were rather a way to study it and to gain inspiration. In this large collection of anonymous women (allegedly mostly dancers from Turin), each woman has become a study: of the female body, of her nubility. But she has also become a thing—one amongst the many in the villa. Carlo Mollino added the women he photographed to his collection of things housed in the villa. Briefly they were there in person, afterwards they stayed as photographs.

I’m not calling Mollino’s photographic practice aggressive. If we do look at the collection of Polaroids as a collection of trophies, there is nothing wrong with having or wanting trophies (or inspiration); it is not always the case that one has to act aggressively in order to win a trophy. However, Mollino’s Polaroids seem to represent photography’s ability to capture the world; here, women are captured in the name of art.

There certainly is basis for talking about the camera as an aggressive device, about photography as a way of capturing the world. There are photographers who wield their cameras in an aggressive, intrusive way. But that’s not the only way to think about or to do photography.

II

Sergio Larrain (1931–2012) was a Chilean photographer. He was a member of the famous photo agency Magnum Photos for a little over ten years. Invited by Henri Cartier-Bresson himself, Larrain became an associate in 1959 and went to work in Europe for two years (his biggest assignment there was photographing the Sicilian Mafia boss Giuseppe Russo, at which Larrain succeeded; also, some photographs Larrain took in Paris by the Notre-Dame in the 1950s, which revealed a couple in them only after they were enlarged, inspired Julio Cortázar to write the short story “Las babas del diablo,” which in turn inspired Antonioni’s Blow-Up). In 1961, Larrain returned to Chile and became a full member of Magnum—although he was no longer really doing the kinds of journalistic assignments other Magnum photographers were working on. In the late 1960s, Larrain becomes more absorbed in spiritual growth, and in 1972 he ceases to be a member of Magnum Photos. Larrain retreats to the North of Chile in order to engage himself more fully in spiritual practices—such as meditation and yoga—as well as calligraphy and painting. Sergio Larrain was as much a photographer as he was a spiritual seeker (and he also had a vision for a different society than the business-oriented and environment-destroying one he saw around himself, but that’s outside the scope of this essay). The focus of this essay is Larrain’s most famous body of work—the photographs of Valparaíso, a city in Chile.

Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso (Aperture, 2017)3 is a photobook containing Larrain’s photographs of Valparaíso he took between 1952 and 1992—both while visiting and living there (the majority of the photographs in the book were taken in years 1963, 1978, 1980 and 1992). They are black and white photographs shot on 35mm film; they are beautiful, calm, gentle, poetic photographs showing scenes and details of life in Valparaíso.

Valparaíso is a port city—there is a photograph with fish, long and sinuous ones, slowly dying, if not dead already, on docks on a sunny day; in the background water is glimmering. In the water there are two simple boats, in one of them a man (he doesn’t look like a fisherman) is sitting. Looming behind him, and taking one third of the photograph’s space, is a large ship. Because the fish are so close and the ship is so large, man is the smallest figure in the photograph.

Valparaíso is located next to hills—there are many photographs of the city’s steep, sinuous, narrow streets and steps. “If we walk up and down all of Valparaíso’s stairs, we will have made a trip around the world,” wrote the poet and former resident of Valparaíso Pablo Neruda, whose text on the city serves as the book’s introduction.

There are photographs of cats and dogs. Of leaves and plants living in and adorning the mostly concrete city. There are beautiful photographs taken during and after the rain.

There are photographs showing light interacting with architecture during the day. And there are photographs of Valparaíso’s nightlife.

Perhaps the device with which these photographs were taken is an aggressive one; but the photographs themselves aren’t; the looking of the man who took them wasn’t. The photographs in Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso suggest a calm and gentle process, a meditative process.

In the book, interspersed with photographs, we also find Larrain’s writings, most of them in the form of notes. He writes:

“OPENING THE MOMENT WITH RECTANGLE.”4

“ • Wandering around. . . . In your hands, the magic box. You walk in peace; aware, in the garden of forms.”5

“Undistracted, surprised, enjoying the living sculpture of reality. a glimpse!, you stop. you have the entrance, the veil is out. Like a child in front of a butterfly, slowly, you move, not to loose the frail,”6

“The door opened. awake in the eternal, beauty. Slowly, vertical, horizontal, with infinite care; attention, organising forms as when entering water, or the sun, .. enter the divine. You have crossed time, into the new (into the now); life is renewed.”7

Throughout his life, Larrain practiced meditation and yoga. He wanted to keep his consciousness in a clean state. He led a secluded life. Photography was a way of connecting to the world, of entering into a deeper relationship with reality. In two other notes he writes: “(Entering the present with a craft.)” and “ART IS AN APPROACH TO THE STATE OF SATORI” (satori Larrain defines as being “awoke in the present”).

When he was twenty-one, Larrain spent a year living alone in an adobe house in the countryside of Chile; he “spent the year barefooted, doing yoga.”8 Larrain writes: “During that period, I had my lab and went from time to time to Valparaíso to take photos, and being so clean, miracles started to happen and my photography became magic.” A work done in a clean state will always be a good work—because it is a work done with attention and love, not with aggression, or out of hate, or done purely for accolades or money. But perhaps Larrain didn’t quite take his photographs himself—rather, they came to him. Agnès Sire tells of a “state of grace [Larrain] had to enter in order to ‘welcome’ a great picture . . . as if the images already existed out in the cosmos and the photographer simply acted as a medium.”9 Henri Cartier-Bresson too has said (contradicting his description of photography as “trapping” life in the quotation that I used as an epigraph) that “A photograph is neither taken or seized by force. It offers itself up. It is the photo that takes you. One must not take photos.”10

Theoretical Excursus II

The ancient Greeks believed that ideal forms exist in the universe, and that the artist’s job is to get to and reveal them—as opposed to attempting to create an ideal form himself. If this is true, a question is—keeping it to photography—Does the universe want these photographs to be taken? If the answer is affirmative, we can assume that it will make sure these photographs are taken; which means that the photographer’s effort and skill and training don’t matter that much. Somebody will be chosen and will do the job. Or—yes, the universe has a depository of ideal or great or magical photographs, but it is indifferent to whether somebody takes them or not. If somebody goes after them, the universe will help, but otherwise, as far as the universe is concerned, they might remain untaken.

Kaja Silverman writes that photography is “the world’s primary way of revealing itself to us—of demonstrating that it exists, and that it will forever exceed us.”11 This can be read as suggesting that it is the world itself—not the photographer—who is taking the photographs, or making sure they get taken. If this is the case, the invention of photography wasn’t really up to humans; rather, the world decided it’s time, and gave humans photography. But then what agency have we got left? If the world is taking its pictures by itself? I’m more inclined to believe that it isn’t. The idea of ideal forms, ideal photographs existing out there is appealing, but it’s unclear whether they can actualize themselves without the willed help of a human being, who has to choose to pursue these forms. There probably aren’t that many photographers (but there are some) who have defined their practice as “getting to ideal forms already existing in the universe.” Most just want to take some good photographs—and that might be just enough. We can never fully know what our actions bring about, what their entire effect is. Maybe what we’re doing is manifesting something ideal, we’re just not fully aware of it. Ideal forms and higher orders are realizing themselves through us, without asking us if we want to participate. We are already and always connected to the universe, and everyone is bringing on and manifesting what they have to. Or—ideal forms and higher ways of being are potentially available, but reaching them is one’s personal responsibility (to aim at a possibility). I don’t know. I guess I want us to have some agency; I want there to be work to be done in order to connect to the universe, reach higher states of consciousness, and bring the goods back to the Earth.

Conclusion

Aggressiveness and photography. For Sergio Larrain, the aggressive way wasn’t his. About photojournalism—which could possibly be called an aggressive genre of photography, in which there is the need to photograph the immediate and to say to the viewer—Look, this is happening, this is important!—Larrain said: “I feel that the rushing of journalism—being ready to jump on any story—all the time—destroys my love and concentration for work.”12 Larrain wanted to work slowly, unhurriedly, profoundly. He didn’t want to possess the world by photographing it, he wanted to explore and celebrate it. He was after the essential, the lasting.

Maybe there is something fundamentally aggressive about taking photographs (even if done gently). To take a photograph is to not let the world be—just be, without being recorded. On the other hand, maybe sometimes the world wants to be stopped, it wants to be captured in an image. And that image then becomes a world in itself.

There is, when you get a good picture, a joy—I captured this moment. It is a joy that you managed to stop, if only for a moment, the ever moving and changing world, and you now have that moment preserved. Perhaps you had wanted to take this picture; you wanted to photograph a part of the world that interests you or that you like. And maybe that’s the purpose—to find or create your own little world within the big, entire world (and if you like to photograph, you can photograph your world).

I think good photography neither comes from flat-out aggressively going after the world, nor is it the world laying itself down onto the film or the sensor. It’s something in between: You have to put in some effort, but not overly, it’s not about using force. It’s more about looking, listening, paying attention, applying pressure only when necessary. Sergio Larrain has said that photography is “the result of combining your own inner world with light.”13 Not so much is photography (when it is not done for purely practical purposes) showing an objective world out there, as it is showing the photographer’s subjective inner world.

Is the camera ultimately an aggressive device? Is photography an aggressive medium? I think we shouldn’t get carried away with attributing characteristics to devices themselves. Because it’s not so much about how equipment looks or sounds, or about how it can function, but about how it is used. It is the user of the device/equipment who gives the usage its air. It is the state of being in which a person is operating a device that gives the process—and in photography’s case, the result too—its quality. There are aggressive photographers and there are calm photographers, just like there are aggressive drivers and calm drivers. Big bad muscle cars can be driven gently and with masterful control, and big cameras can be used with tenderness and love (toward the subject matter as well as the craft itself). Photography is who and how is doing it (and probably why matters too).

Sergio Larrain’s Valparaíso shows how photography can be a means for connecting oneself with the world, for establishing a deeper relationship with it. It shows how photography—walking around with a camera—can help look at the world: gently, carefully, patiently, with a sense of wonder. Admittedly, meditation and yoga can teach those things too. But sometimes being in the eternal now doesn’t feel like enough—sometimes you want to look at moments from the past or go, mentally, to someplace else. You can do that through photographs; even better if they’re good, beautiful photographs.

Larrain’s photographs don’t shout: Look! Rather, they gently show one man’s experience in one city. And it’s a beautiful city and a rich experience.

- If you approach this question from a more artistic standpoint, you’ll say that sometimes photographs create new worlds. The artistically unique photographs do that. But, as we know, the vast majority of the world’s photographs look kind of the same, so it’s not really merited to say that every single photograph has created a new world. Kind of, but not really. If, however, you approach this question from a more philosophical standpoint, you have to admit that every photograph creates a new world, because every photograph shows the world in a new moment in time—and in time the world moves—it looks differently.

- If somebody is inclined to condemn Case History because of what the photographs show, they should really be condemning the socioeconomic conditions which, so to speak, produced those lives that Mikhailov has photographed. That would, of course, have to be a critique of both Communism and Capitalism. There obviously are homeless people in Capitalism, maybe less so in Communism; but Communism in practice seems to be bound to bring violence, oppression and misery (more so than Capitalism does). And especially ruinous can be the period when one system transforms into the other.

- Valparaíso, the photobook, was first published in 1991 by Agnès Sire, who worked at Magnum Photos and had at the time already corresponded with Larrain for some years (they kept sending letters to each other until Larrain’s death), and French publisher Éditions Hazan. Soon after publication, Larrain began to work on a new dummy—one which would include forty years of Valparaíso photographs as well his writings and spiritual teachings, and even few paintings. In 1993, he sent the finished dummy to Sire, and it is now the book Aperture published in the US in 2017, Thames & Hudson published in the UK in 2017 and Xavier Barral published in France in 2016. The long gap in time between the dummy being finished and its publication is because after the success of the first book—which accompanied Larrain’s exhibition at the Rencontres d’Arles photo festival in France in 1991—an interest in Larrain was sparked, and exhibitions around the world followed. Although pleased with the 1991 success, eventually Larrain decided he does not like the attention he was receiving (in 1999, the Valencia Institute of Modern Art held a retrospective for Larrain, which he regarded as unwelcome) and he decided not to publish any more books during his lifetime. There was, however, an arrangement to posthumously publish this Valparaíso volume, which was Larrain’s “100% on the city . . . and on everything else” (“Sergio Larraín: the poet of Valparaíso” by Simon Willis, Financial Times).

- Larrain, Valparaíso, 26

- Larrain, Valparaíso, 28.

- Larrain, Valparaíso, 33.

- Larrain, Valparaíso, 45.

- Larrain quoted in Agnès Sire, “Planet Valparaíso,” an essay accompanying Valparaíso (Aperture edition), 182

- Sire, “Planet Valparaíso,” Valparaíso, 188.

- “29 Quotes by Photographer Henri Cartier Bresson.” John Paul Caponigro – Digital Photography Workshops, DVDs, EBooks, 21 Mar. 2014, www.johnpaulcaponigro.com/blog/12018/29-quotes-by-photographer-henri-cartier-bresson/ Accessed: 4 Apr. 2019

- Kaja Silverman, The Miracle of Analogy, 10.

- Larrain, Valparaíso, 197.

- Larrain, Valparaíso , 188.