The image analyst is the medium of interpretation, the medium through which information is both constructed and lost.

Topologies of Vision

Location unavailable.

We often describe our world as an information society. Everywhere the character of data is presented as that of the substratum of experience, the stuff by which we come to know the world. And if we think about information in this way, as a media, we can trace its character as a history of interpretation: a history of the methods by which we arrive at knowledge and the forms in which we render it. A certain visual form, the photographic image, is often elided in its coincidence with information, its communicative posture. It is granted the status of self-evidence and clarity: an offering born in the halls of national intelligence.

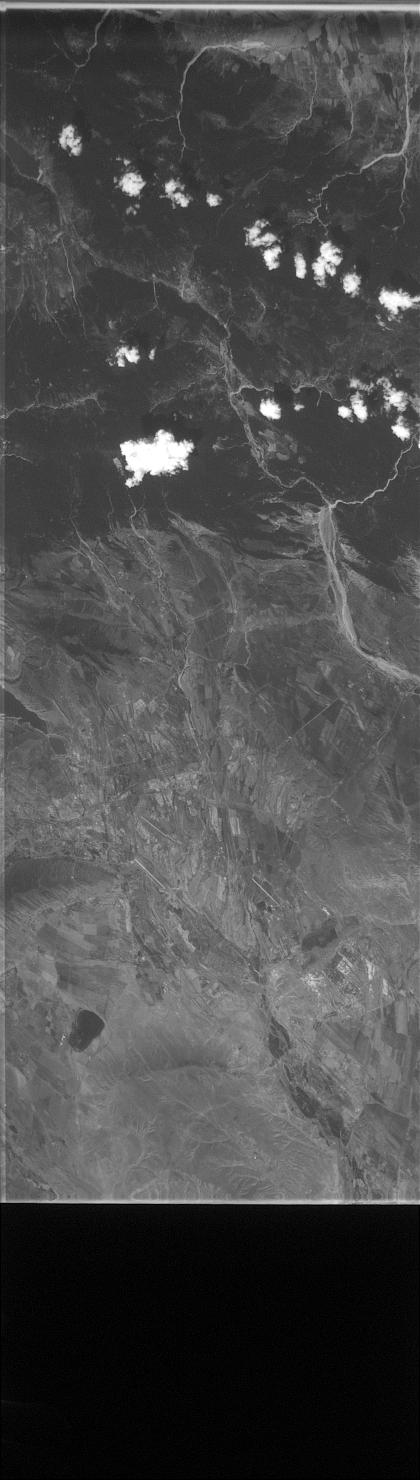

ур. Неце, Хваршинский сельсовет, Tsumadinsky District, Russia

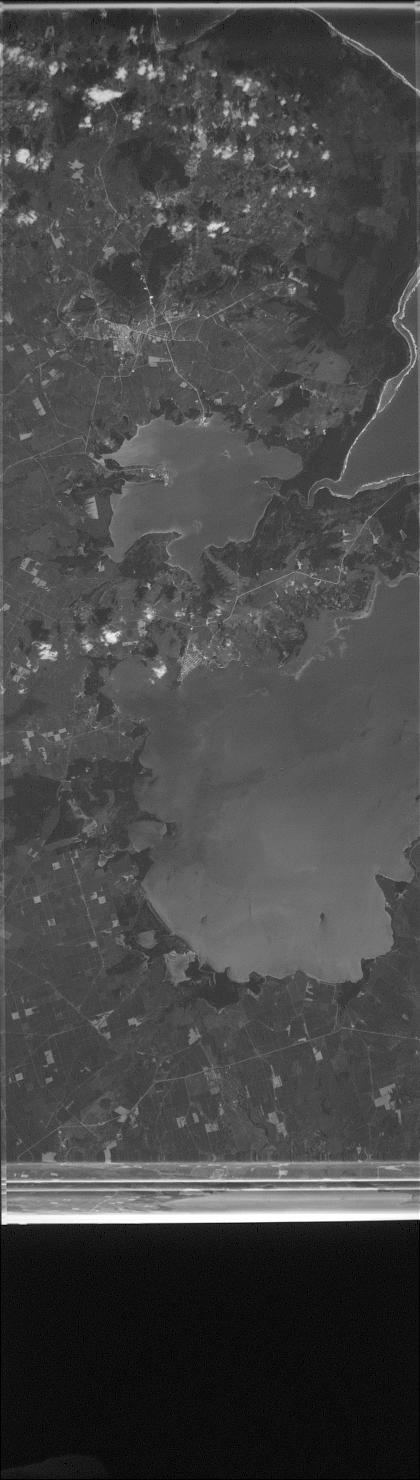

In July of 1963, the GAMBIT satellite was launched into space by way of California. It was the first reconnaissance satellite capable of high resolution photography; in the images its Kodak camera produced, one could distinguish on film between objects two to four meters apart. It was a tool to monitor the Sino-Soviet bloc during the height of the Cold War, meant to register the contours of missile silos, providing the American intelligence apparatus with the clearest images of enemy territory and infrastructure.

Insofar as these images were intelligence, or objects of utility and instrumentality, they functioned as transparent windows into an otherwise opaque world behind the Iron Curtain. As Ronald Reagan would say nearly two decades after the satellite’s decommissioning, “GAMBIT photographic clarity has yet to be surpassed.”

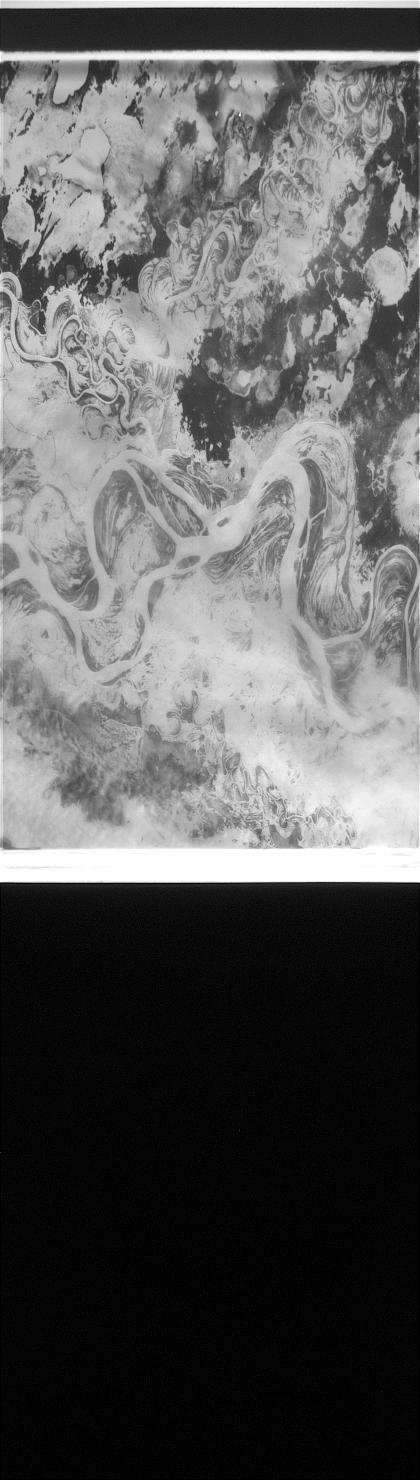

Колпашевское городское поселение, Kolpashevsky District, Russia

The high-resolution image was thought of as the perfect data; it encoded all information, revealed all truth. It was bound to the construction of intelligence, information, and seeing as prior to and ready for interpretation. One can see photography come into itself, find itself nearly independent of the analyst at all. The high resolution satellite image was given the status of self-evidence, bringing forth the missile without the intervention of the grainy camera.

In other words, this transparency of the photographic interface, the sense that high resolution would overcome photography as mediation, here joined realism and surveillance under the sign of intelligibility. The images seemed to open the state’s vision onto Soviet territory, a texture of information.

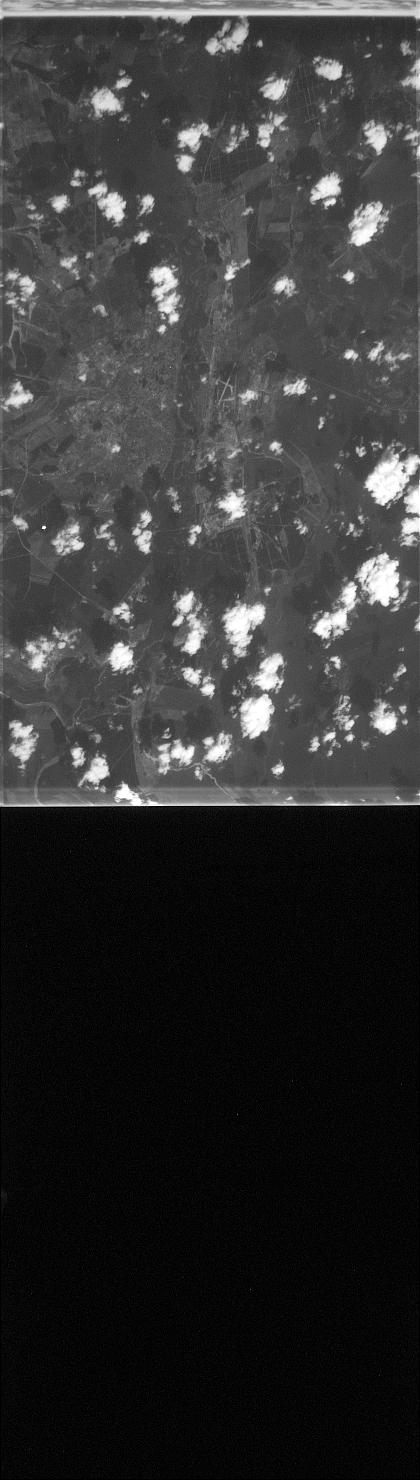

переулок Мостостроителей, 3, Levoberezhny District, Voronezh, Voronezh Oblast, Russia, 394007

For Walter Benjamin, photography opens the “clear field where all intimacy yields to the clarification of details.” GAMBIT’s images were the achievement of this alienating paradigm of clarity, their fidelity superseded by transparency, their “details” the features of a Cold War landscape. And while photography more generally often promises this immediate relationship, GAMBIT’s clarity was oriented toward a particular desire. As one intelligence officer said, with GAMBIT one could not only see a missile silo but measure the thickness of its walls, for instance, to determine the proper trajectory of American nuclear warheads poised for launch. The clarity of these images in their high resolution positioned them as a means of access and knowledge with a particular object in mind.

Verkhnesaldinsky Urban Okrug, Russia

But clarity is not self-evidence. Indeed when attending to photographic images one is interfacing with the world, even more so when those images are operationalized, animated as evidence and reference. And with GAMBIT, the interpretation of satellite images still relied on human photoanalysts. At the same time that computer recognition programs were being developed, GAMBIT images were still part of a process of human recognition. Image analysts would decode the blurs and contours of each photograph, through a process of photogrammetry, or the science of dimensions and spatial relationships in images. In the 1850s, a building surveyor for the Prussian government wanted to avoid the risk of falling off buildings––combining a photographic camera and measuring system. Photogrammetry is a science born from the anxiety of risk, the condition of distance. It is the same science used for rendering in Google Maps; it orients us toward the visualized world.

This orientation was born in the context of national intelligence, of making images intelligible to their users. Analysts at the time were able to recognize patterns in the data of the photograph, to register features against a bank, an archive, of prior images: of launch sites, silos, railway networks. By the mid ’60s, personnel would be the smallest object on that list.

Eventually this process became automated, as object recognition was a paradigm of computer vision research throughout the sixties. The images from GAMBIT, of which there are about 19,000, were used to train early geographic intelligence programs; contemporary mapping technologies, much of NASA’s satellite imaging––such are the things predicated on the once-human ability to parse a missile from a pine tree.

unnamed road, El Alto, Bolivia

In a promotional video for GAMBIT, Arthur Lundahl, then the director of photointerpretation, espouses the success of the satellite’s missions, the thousands of images that have been of such use. It reminds him, he says, of a quote by the Ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes: “Give me a place to stand and I will move the world.”

This quote is a misreading, an omission. Archimedes said “Give me a place to stand, and a lever long enough, and I will move the world.” The legitimacy of these images are predicated on the erasure of this lever, so to speak––the lever of their mechanical production and of their interpretation by human labor. Their achievement is their obfuscation as media.

In the case of GAMBIT, intelligence came from both the image and the analyst, joined in a process of indicating what counts as data. The image analyst, measuring all the features of missile silos in an office cubicle, destabilizes this apparent independence of the image as information. The analyst must bring forth the photogrammetric understanding of the object; exactitude was a virtue that served the media as much as it did the analyst.

Banes, Holguín, Cuba

A 2000 report by the National Imagery and Mapping Association, the subsequent name of what was the NPIC, describes the electronic geographer as trading in data, responsible for measuring and recording distinctions in an image. The imagery analyst is different:

The image analyst is about ‘storytelling’-like the legendary native scouts who could read subtle signs in the dust to recount the passage of game.

The image analyst does interpretation; she is akin to an ancient augur, the priests who would interpret the will of the gods through the behavior of birds. The image analyst is the medium of interpretation, the medium through which information is both constructed and lost.

For the purpose of textual histories, the image analyst offers a paradox without substitution, a way out of the clarity fetish, a collapse of unity and reproduction. The analyst depends on an intelligence contingent upon and yet distinct from the image at hand. She operates outside the sign of resolution and measurement, outside a false totality of empiricism. Her media are the birds of augury.

Berestechko Urban Hromada, Lutsk Raion, Ukraine