By disguising these essential structures of infrastructure as detached homes, the transformer houses embody and display a fetishization of suburbia characterized through homogenized architecture.

Aesthetics Unveiled

Exploring the Physical Qualities and Political Dimensions of Concealed Infrastructure

If you look at an aerial view of Toronto at night, it would show a region illuminated by countless lights. If you zoom in, the neighborhoods surrounding the city center would unfold, revealing a mosaic of detached houses interspersed with occasional larger buildings. The windows in most buildings might be illuminated offering a glimpse into the lives of the inhabitants, however, not all the houses would be lit up. This would be the case for 555 Spadina Road, a Georgian Revival mansion in the prominent neighborhood of First Hills, which would remain dark. The truth is, this “house,” like hundreds of other structures around Toronto, is not an active residence but a facade that covers electrical transformer equipment used to power the surrounding neighborhood. Around two hundred of these structures were built by Hydro One’s predecessor organization, after electric power first came to Toronto from Niagara Falls in 1911. According to Chris Bateman, a Toronto based journalist who explored these houses in a 2015 magazine article, several of the buildings have been decommissioned, however, over seventy-nine active sites remain scattered across the city and its surrounding suburbs.1

This phenomenon of concealing infrastructure within aesthetically uniform facades is not unique to Toronto. Metropolis areas such as California, New York, and London contain their own share of fake buildings which host a variety of electrical and ventilation infrastructure.2 However, given Toronto’s notably high number of these transformer houses, it serves as the focal point of this paper’s examination into the mechanisms behind the decisions to conceal vital pieces of the city’s infrastructure behind ornate facades. Through visual analysis, this paper explores how these transformers embody politically motivated ideals of city uniformity and concealment, perpetuating a cityscape where essential infrastructure remains hidden. The paper begins by introducing previous scholarship on the topic and by defining the central frameworks through which I will conduct my analysis. I then provide historical context for the development of electricity in Toronto. I then proceed to a discussion of the practical motivations behind substation concealment and transition into an analysis of their embodied ideals and political qualities. I conclude with a brief reflection regarding more recent applications of transformer infrastructure and provide a radical note on a suggested path moving forward.

Defining Frameworks

The etymology of the term infrastructure originates from nineteenth century French railroad engineers and has since evolved into a general association of the equipment, structures and systems that are needed for society to function smoothly.3 The authors of Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases articulate how the concept of infrastructure has garnered considerable scholarly attention given that its development allows powerful entities to mold society according to their preferences.4 Under this framing, early analyses primarily centered on defining infrastructures’ relationship to the modern state, capital, and empire.5 Scholars such as James C. Scott have explored how modern state logics, such as the implementation of city grid systems, were influenced in part by their practicality in facilitating the installation and operation of infrastructure.6 Other scholars, such as the authors of The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure: Race, Affect, Environment and anthropologist Brain Larkin in his work “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” have since taken on infrastructure in terms of its cultural affect and relationship to space as considered through critical geography, architecture, and design studies.7 The following analysis on transformer houses in Toronto aims to pull from this developing body of scholarship to explore how the structures operate on both political and cultural levels.

For Larkin, infrastructure serves as the foundation upon which other elements function and because of this characteristic, it should be defined in terms of systems.8 In her 1999 article “The Ethnography of Infrastructure: PROD” Susan Leigh Star gives several criteria for defining infrastructure as drawn from ethnographic field studies. Key to Star’s definition is the idea of infrastructure as embedded, or “sunk into and inside of other structures, social arrangements, and technologies” and that infrastructure “both shapes and is shaped by the conventions of community practice.”9 These two definitions help to frame the internal equipment and the ornamented facades of the Toronto substations as intertwined systems, whose technical functionality is embedded into the social configurations of the houses’ exteriors. Given that the external structure and the substations’ internal equipment cannot function separately without major system reconfiguration, this paper considers them as a single piece of infrastructure. Under this lens, there arises both a political and cultural question regarding why these transformers are concealed with such high levels of aesthetic detail when concealment is not necessary for the equipment to perform its function of converting electrical currents.

Larkin advocates for a reading of infrastructure through its poetic form, in which system operations are considered on symbolic and affective levels beyond purely technical functionality.10 At the same time, Star emphasizes a need for considering the physical qualities of infrastructure which shape the way landscapes and communities interact with them.11 In this analysis, drawing conclusions regarding the positionality of the transformer houses of Toronto requires consideration of how the physical and affective qualities work together to shape the urban landscape. This lens of study brings into focus the desires and fantasies embedded into the external facades of the transformer equipment, which operate autonomously from their technical function, allowing for a consideration of how politics are injected into infrastructure on different levels. Subsequent work by Rich et al., takes on the ideals of infrastructure poetics and adds a level of embodied esthesis to Larkin’s analysis, considering the experience of infrastructural material qualities in the context of chronology and setting.12 Through a close visual analysis of both historical and contemporary images of the Toronto substation houses, this paper formulates conclusions on how the physical detail of the houses’ facades embody politically-driven ideals of suburban uniformity and homogeneity, which propagate a version of urban life that operates without visible technical interventions. Within this, the analysis is attuned to the historical contexts and material conditions which shape the physical practicalities of these houses. My analysis ultimately calls for a restructuring of the way infrastructure is applied within cities in order to create a level of transparency and understanding of the technologies that power our everyday lives. By peeling back the layers of these houses, one can see the multiple levels of systems operating behind their facades.

Setting the Scene for Hydro in Toronto

According to an online exhibition created by the city of Toronto archive department entitled “Turning on Toronto,” Ontario began to push for the development of hydro-electric power at the beginning of the twentieth century to seek relief from a dependence on American imported coal.13 The natural resource of Niagara Falls was positioned as the key source of hydroelectric power. In 1904, The Electric Development Company, one of three companies granted rights by Queen Victoria Niagara Falls Park Commission, began constructing an ornate powerhouse and transformer station designed by Edward James Lennox to deliver power to the city. This was the start of a series of ornate building projects surrounding electrical infrastructure in Toronto.14 Once power was flowing to Ontario, tensions grew between municipalities and public companies over who should control its distribution. Larkin points out that, “often the function of awarding infrastructural projects has far more to do with gaining access to government contracts and rewarding patron-client networks than it has to do with their technical function.”15 The contested debates over ownership and the involvement of high-ranking businessmen in shaping city decisions is outlined in an archive exhibition and demonstrates the political forces that shaped Toronot’s hydro electric systems establishment. In the end, municipal control prevailed and in 1906, the Ontario Legislature established the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario (HEPCO) and passed an act to position HEPCO as the wholesaler of hydro-electric power, while municipalities acted as retailers.16

Power reached Toronto over publicly-owned and provincially-controlled transmission lines from Niagara on February 24, 1911.17 HEPCO later became known as Ontario Hydro which was subsequently restructured into separate entities and the transmission and distribution of electricity now falls to Hydro One which is owned by the government of Ontario.18 The municipal company Toronto Hydro, owned by the city, purchases electricity from Hydro One and distributes it to local residents.19 According to an article by Adonis Yatchew on electricity in Ontario, approximately 70 percent of the power delivered in Ontario is delivered by these municipal utilities and serves 2.8 million customers.20

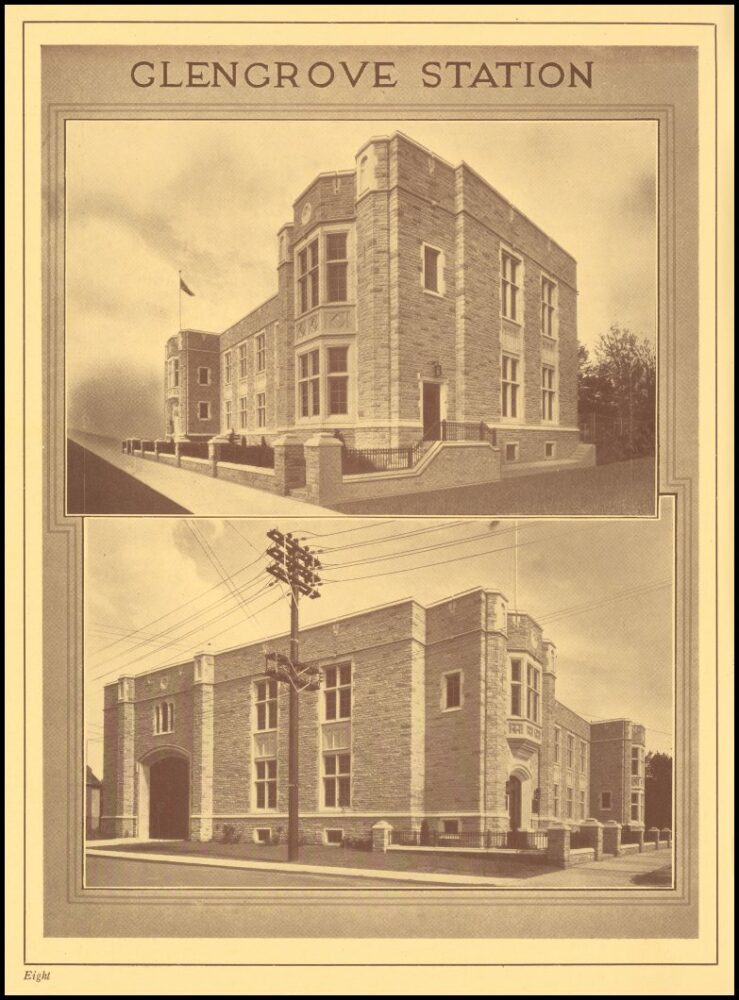

When power first came to Toronto, the city lacked the necessary infrastructure to distribute it. To remedy this, HEPCO created a sub-department called Toronto Hydro-Electric System (THES) to oversee the construction of electrical distribution infrastructure throughout the city.21 According to the Toronto archive exhibition, “in order to provide well regulated service to its customers, the Toronto Hydro-Electric System had to have a sufficient number of substations, properly located from an engineering standpoint.22 While it’s widely understood that most people desire access to electricity, many individuals would rather not have substations located right next to their residences. To combat this situation from arising, camouflage exteriors were applied to the Toronto substations from the start. Images from the Toronto city archive depict early substations like the Parkdale station built in 1928 and the Glengrove station built in the 1930s as designed to resemble grandiose structures (fig. 1). The Glengrove station takes the form of a massive castle-like structure made of pale stone with front facing turrets and elaborately inset windows covering the entire exterior. The side of the building features ornate curved wooden doors and the exterior, according to Google satellite images, is well maintained with a mowed lawn and manicured shrubbery (fig. 2). The exterior presentation of the transformer resembles its neighboring buildings, as can be seen in fig. 2, directly to the left sits an equally large red brick apartment building with similar landscaping. It is clear that from the start, THES went to great lengths to blend transformers seamlessly into their assigned locations.

It wasn’t until later in the 1940s, during the post-WWII construction boom, that THES began designing substations to look like the small single home residences that were “popping up all over newly developing areas in Toronto.”23 According to Google map pins created by Chris Bateman for his magazine article and cross-referenced with city property records, the houses are distributed throughout Toronto, spanning from densely-populated urban centers to the surrounding suburban areas.24 The houses exist in a variety of architectural styles, ranging from model cottages to large mansions. Breakers and voltage dials were built into the main part of the house and the larger equipment necessary for converting high voltage electricity was usually placed in an open section at the rear.25 The house’s varied exterior designs clearly aim to blend into the surrounding buildings, as evidenced by the description of the Parkdale substation. According to Steven Jones’s book Cell Tower, the application of transformers in Toronto follows a similar logic to that of telephone poles, wherein design is employed to relegate intrusive objects that need to be deployed in large numbers into the background.26

Practicalities of Material Conditions

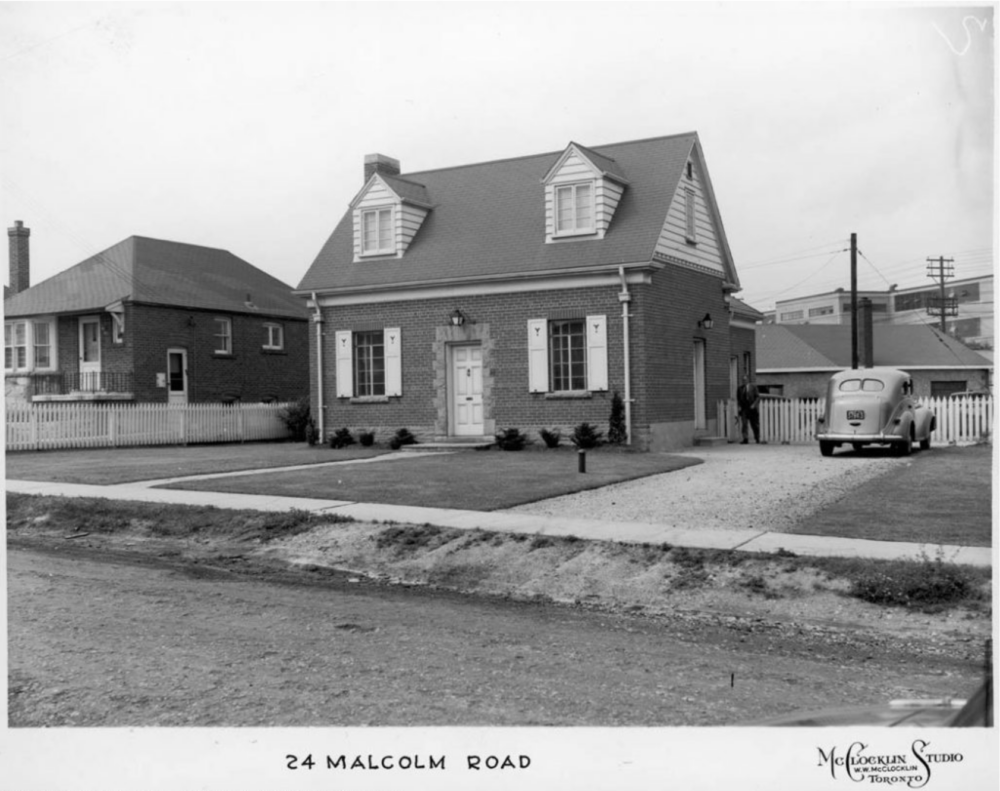

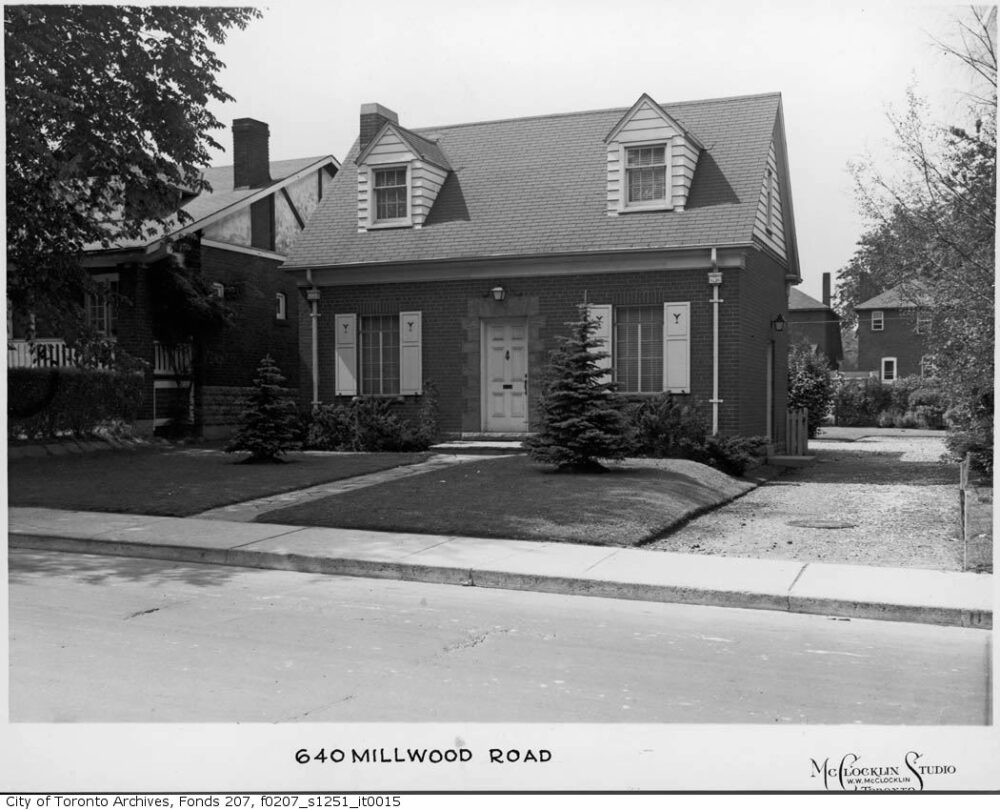

Before delving into an analysis of the poetic nature of Toronto’s substation homes, it is essential to establish the practical reasoning that shaped their physical appearance and technical functionality from the outset. Three images from the Toronto city archive, taken not long after the pictured house’s construction in 1945, show the same model of transformer home at three different addresses: 24 Malcolm Road, 386 Eglinton Avenue East 640 Millwood Road (fig. 3, 4, 5). The structures within the images appear as completely inconspicuous, single family homes, which blend seamlessly with the similar dwellings visible around them. A slightly zoomed out image of the 386 Eglinton addresses shows a manicured lawn and stone path leading to the building’s door which features a slab stone frame and decorative details including an overhead light, door knocker and letter slit. To the door’s side sit two picture frame windows with matching white shutters and drawn blinds. The height and line of the house’s sloping roof closely resemble those of the house on the left and the roof shingles, dormer windows, and chimney mirror features found on the house to the right. These houses and the equipment within them exemplify Star’s concept of embeddedness. Through their exterior design, the infrastructure of the substation is integrated into the surrounding location to the extent that residents may not readily discern its presence. Additionally, to Star’s point of infrastructure reflecting community conventions, the station’s appearances are shaped by conventions of the houses that surround them and due to their permanent nature, they have the potential to influence new construction.

On a practical level, the culturally conventional design qualities of aesthetic embeddedness combat the negative externalities of infrastructure as identified by Filion, Keil and Pulver in their book Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures. These negative externalities arise through infrastructure that embodies qualities such undesirable land uses and visual disruption therefore, depressing the values of close-by properties.”27 A 2020 study conducted on property value impacts from substations found that substations within fifty meters of a property are associated with a 2.9 percent decrease in property value.28 Negative externalities stemming from infrastructure, whether real or perceived, have led to the historical development of The Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) movement, triggering protest and community organization on a variety of scales.29 Filion et al. discuss how infrastructures externalities “breed fragmentation” through creating constituencies that benefit or suffer from infrastructure presence or absence.30 In the case of the Toronto transformer houses, cohesive aesthetic design is used to mitigate association with visual negative externalities effectively reducing factors which stur NIMBY based unrest. Camouflage as an effective solution to NIMBY is also proposed by Stevens in regards to cell towers.31

A further negative externality of the substation, which is combated through its aesthetic camouflage, is the potential health and safety risks associated with its presence. On a practical level, transomer homes pose several safety risks, one of which is the increased probability of fire caused by electrical malfunction. There have been examples of transformer fires in Toronto such as a fire that broke out in 2008 at Fairside Ave. and subsequently cut power to over three thousand surrounding homes.32 Another commonly perceived health concern in regards to proximity to electrical equipment is the effects of exposure to levels of electromagnetic currents. Through their house-like facades, the Toronto substations mitigate perceived risk by visually presenting foreign electric equipment in the culturally understandable and comfortable form of a detached family home. The idea of invisibility as contributing to a lesser perceived idea of public health risks is addressed by Kathrine McNeur in her book Taming Manhattan; Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City. In the text McNeur, looks at the difference in public perception and government intervention between the open practice of hog keeping or offal production as compared to the less visible practice of swill milk production. Analyzing historical news articles and firsthand accounts, McNeur concludes that the exposed visibility of the piggeries and offal production were contributing factors to raised public health concerns and the subsequent increase in government regulation.33 In line with McNeur’s analysis, the less visible nature of the Toronto substations, crafted through their aesthetic facades, mitigates perceived negative externalities. This is evidenced by a lack of significant historical documentation regarding serious objections to them.34

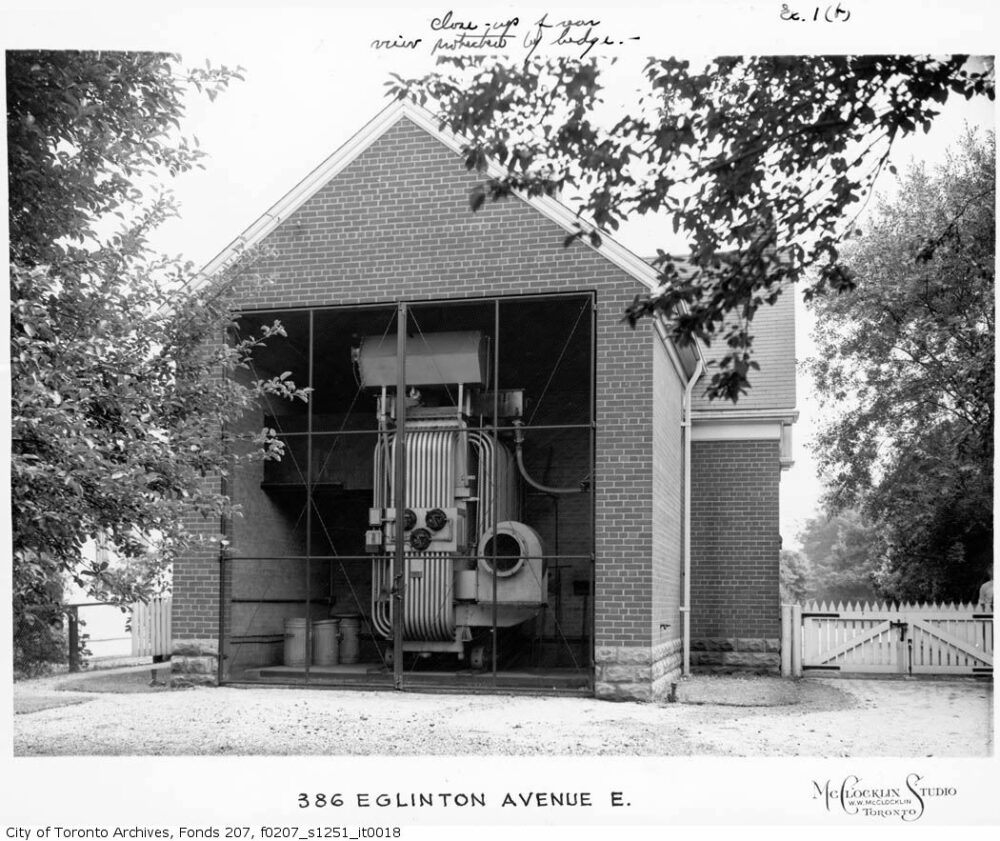

The community experience and reactions toward the transformer houses are constituted solely through their external facade since the general public is not allowed access to the interior spaces. An archival image from 1945 of the backside of the 386 Eglinton Avenue substation tells a completely different story from its front facade (fig. 6). Where a back wall should be, the image shows a large open space, revealing the industrial transformer which visually looks like a mass of intertwining pipes and dials accompanied by an exhaust hole. From this image of the back of the house, a view not witnessed by many, as other homes are bordered on all three sides, it becomes evident that the exterior form of the substation does not align with the house’s interior function. The parts of the interior not visible in the image can be supplemented by an account by Dave Leblanc who, accompanied by Toronto Hydro Corp employee Bill Tutka, was able to enter several of these buildings around 2004. Leblanc notes a slight humming sound coming from the buildings and describes how unlike the outside, the interiors are stripped of ornamentation and very utilitarian. According to Leblanc, the initial impression that the house has two stories is shattered once you enter as there is no actual second floor and where things like a kitchen or living room would be, sit high-voltage switchgear and other various meters, dials and equipment.35

The complexities between this misalignment of the interior and exterior of the transformer houses can be understood through the architectural theories of Kahn regarding the interaction between “served” and “serving” spaces. According to Kahn’s theory, Served spaces are utilitarian spaces that link, shape, and allow the primary space or Served spaces of a building to perform their formal functions. In the article “The Relationship between the Servant Spaces and Served Spaces in Single Families Residential Patterns: Baghdad as a Case Study,” the authors posit that “the Servant and Served spaces relationship is one of the main factors that give houses a specific characteristic, which reflects a certain pattern of a single-family home.”36 In the case of the transformer houses, the expected interior “served” spaces, like the kitchen or living room, are actually operating as “serving” spaces inhabited by industrial equipment that enable the electrical grid to function. This reversed dynamic is not observed by the surrounding community who most likely view the facade as a regular home whose exterior features are in accordance with the aesthetics of the neighborhood. The idea of appearance as superficially constituting perceptions towards architecture is emphasized in the article “This Is Not a Pipe: The Treacheries of Indigenous Housing” where the authors describe how much of Indigenous housing presents visual signs of being functional, however, in reality contains infrastructure that does not technically function at all. They class these instances as creating “composite deceptions” that generate an “aesthetic order” mitigating the perceived need for political action.37 Since the “serving” nature of the transformer houses is masked by the facade of a “served” space, the primary engagement of the structure with the public domain occurs through its exterior. Similar to the Indigenous housing, examination of external aesthetic details hold the key to uncovering the political motivations driving the facades construction.

Star emphasizes the role of relationality within infrastructure, meaning that systems operate on different levels for different groups of people as part of a balance between action, tools, and the built environment.38 Under this, we must consider the practical motivations that shaped the city department’s choice to construct substations under camouflaged and embedded conditions. Again we can turn to the work of Jones who emphasizes the motto of “security through obscurity,” a common phrase used by telecoms who don’t like to advertise the location of their towers, only the total aggregate number.39 The covert treatment of operational information regarding transformer houses seems to be true in Toronto as municipal and state organizations do not have put forth a lot published information on past or current transformers besides ownership records and petitions to update decommissioned lots.40 While the assertion that security drives city decisions to build these transformer houses is worth considering, it is somewhat undermined by the meticulous level of aesthetic detail applied to their facades. This is evidenced through the 555 Spadina Rd. transformer house, whose red brick facade, as viewed from Google satellite images, boasts twenty-one multi-pane windows, nine of which have been fitted with matching white shutters (fig. 7). The sheer amount of windows on the house’s already grand facade challenge the idea of security through obscurity. They both undermine the exterior facade’s existence as an enclosed structure meant to protect the interior equipment through the creation of physical and visual entry points, and they frame the house as a grand spectacle which, rather than blending in, starts to compete with the other brick homes on the block.

Fantasies of Suburbia and the Politics Embedded in Facades

Building upon the houses’ overly aesthetic qualities, this section aims to read the transformers on a poetic level to understand how their form perpetuates political ideals that move beyond their functionality. The same image of the 555 Spadina Rd. shows a neat lawn and stone pathway leading up to a clean facade of red brick with the above mentioned shutter framed windows set into its face. Above the window, clear pains have been taken with the brick work and a section of vertical bricks with a central stone slab frame each window creating a level of visual ornateness. The door is set into a covered entryway complete with pointed roof, inlaid columns and a divided pane half moon window. The pointed roof line features two chimneys suggesting the presence of two active fireplaces to heat the “inhabitants” of this grand home and the yard consists of manicured bushes and several large pine trees all of which have been maintained according to the Google satellite image (fig. 7). It is this extraordinary level of aesthetic detail given to the facades of the transformer houses that goes beyond the physical functionality of blending in as a means of mitigating the perceived presence of negative externalities, which could be achieved with simpler designs. Under a poetic reading, where symbolism is considered beyond technical function, the transformer houses embody a desire for neighborhood uniformity and a fantasy of a city that operates without visible infrastructure.

The facades of the transformer homes enforce an artificial visual order to the neighborhoods they inhabit by creating a homogenous zone of houses striving for traditionally aesthetic ideals of single family suburban residences. This then creates a perceived version of a city free from physical utilities with maintained access to their resources. In the article “The Root and Development of Suburbanization in America in the 1950s,” Jeong Suk Joo defines how a mass development toward suburbanization occurred during the same period that these transformers were constructed. Joo states that moving away from urban centers and isolating oneself in single family residence was seen to offer “pure and unfettered living conditions bathed in sunlight and fresh air,” a retreat from the commercialism and industry of the city.41 Joo states that by the 1890s and beyond, the shift towards moving away from cities and transitioning to homes that facilitated lower densities was spurred by perceptions of city life as undesirable within a time of industrialization. The postwar suburban home became the receptacle of consumer culture, appearance and display.42 Joo cites Kenneth Jackson and his book Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States, to define how the irony of suburbanization was that “amid the dense foliage, somewhere below the streets, pipes and wires brought the latest domestic conveniences to every respectable home.”43 The transformer houses, with their deceptive facades, embody this irony, concealing the very infrastructure that makes suburban life possible. A review of John Sewell’s book The Shape of the Suburbs: Understanding Toronto’s Sprawl reveals a similar narrative of suburbia taking shape in Canada. Sewell, who served as the mayor of Toronto in the 1980s describes how government officials and city planners favored the development of suburbs through the application subsidies and zoning laws.44 The population of metropolitan Toronto doubled from the 1950s to 1990s, but the amount of urbanized land more than tripled from 193 to 656 square miles.45 Most new suburban development occurred at densities of six to tenresidential units per acre, half the density of Toronto’s pre-1945 neighborhoods.46 By disguising these essential structures of infrastructure as detached homes, the transformer houses embody and display a fetishization of suburbia characterized through homogenized architecture.

Filion et al, state that infrastructure serves as a “barometer of the current condition of society” and Larkin establishes that infrastructure can offer insights into the practices of government, religion or sociality.47 Under these framing ideas, the houses’ physical ornamentation becomes a direct gauge of the government driven push for low density and homogeneous residential landscapes, transforming these houses into suburban ideals. These mechanisms can be seen across other examples of infrastructure such as a cellular tower disguised as a Bison at the Terry Bison Ranch in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Steven desibees how the bison, whose deception has a breaking point, becomes a copy not of the animal but of symbols which embody conflicted histories of native culture, settler ideology, old-West adventure, hunting, ranching, railroads, mass extinction, and genocide.48

The visual scrutiny of the Spadina Rd. house and its intricate facade detail unveil design elements such as the window which reflects the politics of suburban ideals. These features strive to convey the illusion of habitation so convincingly that one might assume at first that actual residents occupy the premises. Even the maintained yard which is neatly mowed propagates suburban ideals as Joo defines, that sports such as golf influenced suburban development and houses with well-groomed yards were promoted as an extension of the golf course.49 Despite these characteristics, if you were to approach it, like the bison, the exterior face of the house would melt into the plain truth. Just visible in the Google satellite images are warning notices on the front door and sealed side gate. These clues reveal that the house does not host a nice family but is home to an array of industrial equipment. The facade becomes significant through its symbolic life that outlasts its ability to physically deceive a passerby. As Larkin positions, the “houses operate on a level of fantasy and desire.” They become the vehicles through which ideals, stemming at the government level, are transmitted and made emotionally real to the inhabitants of the city through their aesthetic influence on the ambient conditions of everyday life.50

The authors of The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure, provide a frame of analysis that looks at the relationship between infrastructures embodied poetics and physical characteris to reveal political operations.51 If we interpret the encoded nature of the houses’ facades as revealing ideals of a uniform city, created through the governmental bodies in charge of their construction, we can draw conclusions about the political rationality underlying technological projects and the emergence of an “apparatus of governmentality.”52 Through regulating the construction of transformers to follow the ideals of suburbanization, the government, as Filion et al. puts it, secured their own “dominant interests to shape society in a way that reflected their values . . . thus further enhancing their power.”53 As established, government values at the time of the substations construction across the 1930’s-60’s consisted of facilitating suburban sprawl through supporting policies. These houses, like many other pieces of infrastructure, claim to function on a physical level by reducing associated negative externalities of infrastructure. Yet, at the same time, they function on a state level, gaining political control over the way certain residential landscapes are perceived both from in and outside perspectives.54

By aligning the transformer houses of Toronto with the political motivations of suburbanization during that era, these houses become landmarks that may later stand out precisely because they lack inhabitants to drive the evolution of their exteriors in line with societal changes. This can be seen in an image of 386 Eglinton Ave. taken by Chris Bateman around 2014, which shows that the two neighboring homes that matched the little house so well in the 1930s have been replaced with two giant towering apartment buildings (fig. 8). A look on Google map satellite images shows that the transformer house has now been removed and a blank plot now sits in its place (fig.9). This is corroborated by a letter from the 2017 Acting Director of Community Planning requesting a permit to add an 11-storey addition to one of the apartment buildings to fill the empty lot.55 Filion et al. state that its difficult to foresee long-term consequences of infrastructures which brings into question infrastructures reliability to attain long-term societal objectives.56

Current city treatment of transformer buildings across Toronto is irregular. According to conversations between Dave Leblanc and Tom Fotinakopoulos, a supervisor with Hydro’s Facilities Management Department, the active transformer houses are maintained by the city. This upkeep serves the dual purposes of keeping the neighborhood content and addressing safety concerns.57 On the other hand, many of the houses have fallen into disrepair or have been decommissioned, such as the transformer at 386 Eglinton. By integrating social ideals into the inanimate facades of the transformer houses, the city created a network of buildings that do not adapt alongside modern needs. Without constant management, which Joo posits as a defining quality of homogenous suburban living, the houses fall into disrepair directly contradicting the political motives which constructed them. This creates a paradox between the physical state of these houses and their relationship to infrastructure as the “technological conditions [which provide] cultural experiences of modernity.”58 Through the slow decay and decommission of these structures, it becomes clear that the physical materiality of the houses’ facade is a poor medium through which to embed social fantasy, because it lacks the ability to adapt its technical appearance to fit changes in government positionality and social ideals.

Conclusions

Newer substations constructed in Toronto and other cities maintain elements of external concealment, however, their facades reflect more modern design sensibilities and do not strain as hard to conceal the technical function of the equipment they contain. This can be seen by Google satellite images of one of Toronto’s newer substations located at 51 Blackburn St. which was built around 1988.59 The station is large and boxy with no slated shingle roof. Windows seem to be minimal and decoration is provided through frosted glass squares which hint at the electrical equipment inside (fig. 10). This kind of half concealment of infrastructure is reflected in New York City at Mulry Square, where a subway vent, built in 2011, sits half concealed behind a corner piece of brick facade affixed to the rest of a concrete brutalist structure.60 This presents the off putting visual effect of clearly indicating that there is industrial equipment that is halfway being concealed (fig. 11). Though adapted, these newer applications of infrastructure still embody aesthetic decisions that aim to embed technological equipment into its surroundings in a way that mimics other buildings and negates a recognition, by the passerby, of the structure’s technical functionality.” Filion et al claim that “infrastructures contribute to extending the neoliberal-induced polarization of society by differentiating conditions available to different social classes and further separating classes from each other.”61 After analyzing the deeply political motivations which shape infrastructure application, I’m inclined to argue for a radical approach in which systems like transformer stations should be constructed in a way that makes them fully visible to the public eye. Disparities in infrastructure across class and race can never be fully recognized and remedied if we continue to cover up and veil the systems and technologies that both serve our modern needs and create our modern divides. As we face a future full of uncertainties regarding the environment and the impacts our cities, especially energy consumption, pose to it, the decisions to shroud infrastructure in aesthetics create conditions in which community resource use and imbalances cannot be fully recognized. In order to effectively comprehend and address the precarious state of societies, we first need to make visible the mechanisms that have brought us to where we are today.

- Chris Bateman, “The Transformer Next Door,” Spacing, issue 37 (2015).

- Roman Mars and Kurt Kohlstedt, The 99% Invisible City: A Field Guide to the Hidden World of Everyday Design, (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2020).

- Kelly M. Rich, et al., The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure: Race, Affect, Environment, (Northwestern University Press, 2023), 1.

- Pierre Filion and Nina M. Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases, (University of Toronto Press, 2019), 16.

- Rich, et al., The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure, 10.

- James C. Scott, Seeing Like a State: Why Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (Yale University Press, 1998), 57.

- Rich, et al., The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure, 12.

- Brian Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” Annual Review of Anthropology 42, (2013), 329.

- Susan Leigh Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure” The American Behavioral Scientist 43, no. 3 (1999), 381.

- Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” 335.

- Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” 387.

- Rich, et al., The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure, 6.

- The text for the Toronto City Archive online exhibit is based in part upon an earlier exhibit produced in 1991 at the Market Gallery. See “Turning on Toronto: A History of Toronto Hydro.”

- The original transformer station still stands today at 451 Davenport Road however is facing several updates to help externalities such as noise. See “Bridgman Transmission Station.”

- Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” 334.

- “Turning on Toronto: A History of Toronto Hydro.”

- “Turning on Toronto: A History of Toronto Hydro.”

- “Corporate Governance,” Hydro One, Accessed May 1, 2024.

- “Governance,” Toronto Hydro, Accessed May 1, 2024.

- Adonis Yatchew, “The Distribution of Electricity in Ontario: Restructuring Issues, Costs, and Regulation,” in Ontario Hydro at the Millennium: Has Monopoly’s Moment Passed, ed. Ronald J. Daniels (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1996), 337.

- “Turning on Toronto: A History of Toronto Hydro,” City of Toronto Archive.

- Substations are still a vital part of the electrical grid. They work by stepping down power which is brought through the grid at varying levels into a voltage that can be accessed by the houses they serve. Transformer substations are designed to support and transform lower voltages for household consumption. See “What is an electrical substation?,” Repsol.

- “Turning on Toronto: A History of Toronto Hydro,” City of Toronto Archive.

- City of Toronto, By-Law No. 374-1999 (June 1999), https://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/bylaws/1999/law0374.html; Bateman, “The Transformer Next Door.”

- Bateman, “The Transformer Next Door.”

- Steven E, Jones, Cell Tower, (Bloomsbury Academic, 2020), 64- 65. The individual architects and designers of the Toronto substations remain unknown, see Dave Leblanc,“Home, sweet ohm.” This aligns with Jones’s work as he emphasizes that cell towers are most often designed by anonymous contractors and staff engineers.

- Pierre Filion, Roger Keil and Nina M Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases (University of Toronto Press, 2019), 18.

- Ted Tatos, Mark Glick and Troy A. Lunt, “Property value impacts from transmission lines, subtransmission lines, and substations,” Appraisal Journal (Summer 2016), 18.

- Tom Coppens, Wouter Van Dooren, and Peter Thijssen, “Public Opposition and the Neighborhood Effect: How Social Interaction Explains Protest against a Large Infrastructure Project,” Land use policy 79 (2018), 633.

- Filion, Keil, Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases, 18.

- Jones, Cell Tower, 46.

- Sunny, Freeman, “Hydro fire cuts East York power,” Toronto Star, (December 2008).

- Catherine McNeur, Taming Manhattan: Environmental Battles in the Antebellum City (Harvard University Press, 2014), 171.

- According to consultation with Reference & Digital Engagement archivist, Paul Sharkey, the city does not have any significant known records regarding protest or dislike over the transformer houses; however this was based on brief consultation.

- Dave Leblanc, “Home, sweet ohm,” Special to The Globe and Mail (2015).

- Israa H Karam Ali and Inaam A Al Bazzaz, ”The Relationship between the Servant Spaces and the Served Spaces in Single Families Residential Patterns: Baghdad as a Case Study,” IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 1090 012095 (2021), 12, doi: 10.1088/1757-899X/1090/1/012095.

- Tess Lea and Paul Pholeros, “This Is Not a Pipe: The Treacheries of Indigenous Housing,” Public culture 22, no.1 (2010), 191, doi:10.1215/08992363-2009-021.

- Star, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” 377.

- Jones, Cell Tower, 3.

- See City of Toronto. By-Law No. 374-1999 and 368 – 386 Eglinton Avenue East – Zoning By-law Amendment Application – Request for Direction Report.

- Jeong Suk Joo, “The Root and Development of Suburbanization in America in the 1950s,” International area studies review 12, no. 1 (2009), 68, doi:I410-ECN-0102-2012-340-000230397.

- Joo, “The Root and Development of Suburbanization in America in the 1950s,” 68.

- Suk Joo, “The Root and Development of Suburbanization in America in the 1950,” 69.

- Michael, Lewyn, “How Suburbia Happened In Toronto,” review of The Shape of the Suburbs: Understanding Toronto’s Sprawl, by John Sewell, Digital Commons @ Touro Law, (2011), 310.

- Lewyn, “How Suburbia Happened In Toronto,” 300.

- Lewyn, “How Suburbia Happened In Toronto,” 306.

- Filion, Keil, Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases, 28.

- Stevens, Cell Tower, 45.

- Suk Joo, “The Root and Development of Suburbanization in America in the 1950,” 68.

- Larkin, “The Ethnography of Infrastructure,” 333-336.

- Rich, et al., The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure, 4.

- Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” 328.

- Filion, Keil, Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases, 28.

- Larkin, “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure,” 334.

- 368 – 386 Eglinton Avenue East – Zoning By-law Amendment Application – Request for Direction Report, June 2019, Accessed April 20, 2024.

- Filion, Keil, Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases, 21.

- Leblanc, “Home, sweet ohm.”

- Rich, et al., The Aesthetic Life of Infrastructure, 11.

- Leblanc, “Home, sweet ohm.”

- Proposed Emergency Ventilation Plant for the 8th Avenue Subway Line, New York City Transit, June, 2009, Accessed April 20, 2024.

- Filion, Keil, Pulver, Critical Perspectives on Suburban Infrastructures: Contemporary International Cases, 24.