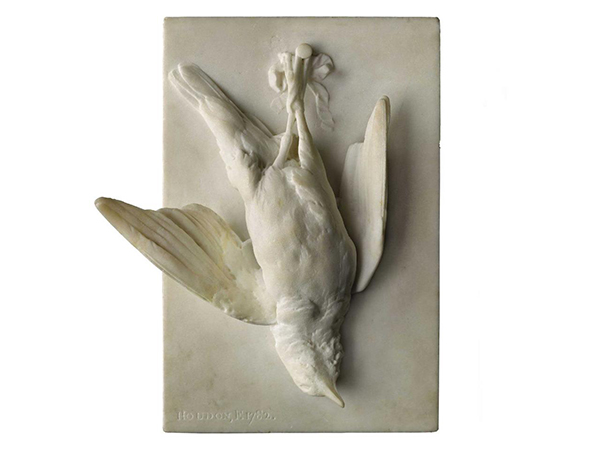

“The sounds of the city echoed outside, but here inside the West Wing, I found myself confronted by a silent figure: a voiceless thrush in a golden frame.” On a relief sculpture by Jean-Antoine Houdon.

La Grive Morte

Shoes clicked down the hallway as light filtered through the long windows. The security guard spoke on the phone under his breath. My papers rustled in my hands as I scrambled to take notes. Voices murmured from other rooms: “Ça, c’est vraiment magnifique”… “Lovely, just lovely”… “That piece, there, is perhaps the most important in the collection.” Outside the walls of the Frick Collection, cars whizzed down Fifth Avenue. Brakes of taxis screeched. Dogs barked. The sounds of the city echoed outside, but here inside the West Wing, I found myself confronted by a silent figure: a voiceless thrush in a golden frame.

I almost passed by it. Then I paused for a moment to turn toward this quiet little songbird, illuminated by a shaft of light from the window. At first I was struck by the simplicity of this piece; it seemed so obvious, so easily accessible. It was not so difficult a metaphor to understand: a silenced songbird, beautifully still and quiet in its death. This had the simplicity of an everyday tragedy: music stops, lives end, and so the cogs turn.

Taken in, I stood there at a moment of collision between this thrush and me, as each of us came upon each other as strangers, sight and sound and life and death mingling together. How did it arrive here, so that I and the others wandering by might be confronted by it? Did it fly, I wondered—one final flight across the ocean from the artist’s workshop, landing swiftly upon this patch of wall. Did those that packed this small marble relief into a wooden crate and loaded it into the plane’s underbelly understand the irony of a flightless bird given mechanical wings?

So many others over the centuries must have been startled by how close this bird looked to reality—surprised by the contoured body and correct anatomy, so close to reality but never quite deceiving the viewer. In the adjacent written description of the piece, the artist, Jean-Antoine Houdon, was compared to the ancient Greek artist Zeuxis, whose realistic paintings of grapes, according to legend, attracted living birds.

And it did seem to deliberately linger in a space between art and reality, between breath and stillness. Its right wing emerged out of the frame and its left wing, although contained within the frame, defied two-dimensional space. The thrush’s body lay open, exposed. With wings open and head thrown back, it was vulnerable, unprotected from others’ invasive eyes. A ribbon tied the two feet together, a place of tension in an otherwise loose form. But instead of imitating its natural coloring, the bird and background were white, luminosity in agony.

This death, I thought, was not a violent death. Instead of blood or broken bones, the thrush’s body appeared unblemished and intact. It had an angelic form, encircled by a vibrant gold frame as if blessed by God himself. The thrush was not so different from the portraits in the room at the end of the hall, those eighteenth century nobles who stared back, immortalized and wrapped in petticoats and cravats and gloves of satin. Like them, the dead thrush was frozen in time, posed and framed and displayed. But while the subjects of these paintings had given permission for their likeness to be captured with paint and canvas, the thrush had never consented to such a state.

The longer that it held my gaze, the longer I began to see the violence taking hold of this little bird, but the violence was not in its death. No, the violence was found in nature of the art itself: the bird would be immortalized in this piece forever, in this artistic cage. Was this one of Zeuxis’ birds, lured in by appealing painted grapes and caught in the artistic realm forever, trapped in a realm of fantasy? Contained there, it was unable to rejoin its brothers and sisters, who enjoyed their mortality and subsequent decay. Instead of, like them, filtering back into the earth and river and sky, this thrush’s end was captured, caged, rendered beautiful and made to be gawked at, handed to us in a pretty package of gold and wrapped up with a bow. What kind of god would condemn it to such an afterlife?

All at once, the wing that extended out toward me was not a plea for life—instead it was a plea for death. The wing that attempted to escape from the frame did not want to lift up in flight, it desired to fall to the Earth and embrace its own decay, to finally be granted permission to disappear. What a privilege it is to be forgotten, one that had not been granted to this bird. Houdon created a sculpture in which the entire objective of its subject was to be liberated from its frame. As it broke through the second dimension to the third dimension, it struggled for freedom.

Will you allow me to die? It asked, as it had asked the artist first, then all those that looked upon it after. Art critics, students, security guards, families, poets, children, artists, lovers—all those who passed by called it beautiful. But could they hear it? Could they hear the songbird’s plea over the sounds of the city?

All that remained was silence.