Do in-prison jobs benefit or exploit the incarcerated?

Prison Labor in the United States

A Historical and Contemporary Analysis

Prison labor has had a long, yet controversial, history in the United States penal system. Under the system of prison labor, some have toiled away for years, sometimes until their deaths, while others have been able to achieve some sense of financial independence or positive mental amendments through their work. Due to these discrepancies in how prison labor has manifested over time in different areas of the country, the system has ultimately produced somewhat mixed results, which subsequently makes it difficult to discern whether or not prison labor can be beneficial to an inmate’s financial and personal self-growth, or if it is simply an exploitative system where the negative aspects outweigh the positive. Prison labor is a multi-faceted business which entails a number of job opportunities across a variety of different fields for the incarcerated population, and, while prison labor can potentially be beneficial to an inmate’s emotional and psychological wellbeing, it is ultimately insignificant in providing a meaningful foundation for self-sufficiency and a smooth transition into free society, and in this light, is a largely exploitative industry that often lacks any tangible positive effect on prisoner’s lives post-release.

History of Prison Labor in the United States (Eighteenth through Twentieth Centuries)

Prison labor is not a novel concept to the United States penal system. In fact, prison labor has existed since the very beginning of American history, going as far back as the post-Revolutionary War, pre-Civil War, era, albeit early manifestations were far more inhumane in comparison to contemporary forms of labor. Furthermore, unlike present-day incarnations of prison labor, which is more or less concerned with promoting rehabilitation and preventing inmate idleness, colonial era prison labor was imposed as means of instilling discipline in unruly penitentiary populations. Convicts who were not facing the death penalty were chained and subjected to public hard labor throughout the day, forced to spend hours repairing roads and buildings before returning to their cells at night.1 Laboring in public was thought to embarrass convicts and deter both citizens and prisoners from committing crime in the future, though this method of deterrence would only eventually create more problems. The idea of prison labor as a disciplinary tactic, arising out of England, was also founded on the grounds of promoting inmate rehabilitation, labor being used in combination with an emphasis on treating prisoners “humanely.”2 By the time this practice arrived in the United States in the eighteenth century, there was hardly anything humane about it, though the perceived humanity of English prison labor was offset by its inherent exploitation of criminals. Besides the fact that prison labor could be brutal, back-breaking work, there was also an exploitative aspect to how penitentiaries “employed” convicts for industrial wage labor, when many of these “criminals” were only engaging in illegal activity—which could range from petty theft to begging—because of a lack of available factory and non-factory work.

When analyzing how labor became a primary mode of punishment in England, the system being introduced as early as the sixteenth century, a few parallels between contemporary American prison labor and colonial-era England become apparent. The modern-day manifestation of the penal system in the United States has been one which houses and contains lower and working-class individuals relegated to the outskirts of society. After desocialized, low-skill wage labor moved overseas for cheaper labor, these people were left with no choice but to engage in illegal or illegitimate modes of work to secure a (somewhat) steady income.3 A similar phenomenon occurred in colonial England, where the introduction of capitalism forced artisans, merchants, and trade workers to submit to the new system of waged labor. Growing masses of displaced and impoverished “free workers” turned to begging or crime (theft) to support themselves, either refusing to participate in the new system of wage labor, or entirely unable to secure work because the sheer number of unemployed workers outnumbered the jobs the fledgling manufacturers could provide.4 The results were paradoxical, as labor would become a form of legal punishment enacted to unfairly use the masses of poor, unemployed, proletariats for cheap wage labor. The contradiction here is that these “criminals,” most of whom were beggars or vagabonds purely because of circumstances concerning their lack of available employment, were punished for being unable to work in the free market by being forced to work through legal exploitation instead.

Though the contemporary American system of prison labor is ultimately quite different from that of the colonial English system, the two systems, however, do bear resemblance in their mutual imprisonment and employment of individuals forced into crime due to rampant unemployment and job unavailability in their communities. While not all jobs offered in contemporary American prisons are tied to capitalist means of free market commodity production, there is somewhat of a paradox inherent in employing the poverty-stricken unemployed through prison labor. Prisoners, in a sense, are “paying for one’s [own] incarceration . . . first in the coin of deprivation, then in the coin of labor,” a dynamic that defines prison labor as two-fold punishment.5 United States penitentiaries would soon start incorporating labor into the prison system, as growing sentiments from the upper-classes regarding havoc and criminal tendencies among the lower-classes convinced governments to use hard labor as a disciplinary, but also potentially educational and rehabilitative tactic—the latter two being a larger focus in modern prison labor. Eventually public labor would create problems of its own, motivating convicts to protest their work or, in some cases, even commit more crimes while working. This led to the incorporation of rigid, scheduled, factory work in Pennsylvania prisons, reminiscent of the industrial labor northern capitalists were incorporating into their workplaces during the nineteenth century. This new form of labor under the guise of Northern industrialization would push craftsmen and artisans out of viable means of income, private enterprises “employing” prison populations for free while the free, unemployed working-classes fought, often unsuccessfully, to find work that was not in a factory and would not have them imprisoned.[6.Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,” 332.]

After Pennsylvania began to “industrialize” prison labor, other northern states eventually followed suit, creating a prison labor industrial complex through a contracting system, one which was exclusive to the North. Realizing that craftsmen who formerly worked within a non-factory, non-industrial context, would not be so easily recruited into the poor conditions and physically exhausting atmosphere of factory labor, northern capitalists turned to prisons to house the factories where prisoners would become the new source of labor. Essentially, through this system of prison contracting, private corporations would purchase a state’s property rights in convict labor, in exchange for the revenue produced through said labor—which could sometimes end up being 150 percent of the original costs of inmate incarceration. .6 Clearly, both the corporations, and the prison administrations, benefited greatly from the contracting system. Prisoners, however, did not.

Inmates forced to work under the northern prison contract system toiled under the pressure of extremely long work days, deplorable workspace conditions, and brutal physical abuse at the hands of prison “overseers,” which included whipping and torture for failing or refusing to work. Adult convicts were forced to work fourteen-to-sixteen hour days while children worked for ten to twelve hours. Outside of punishment, work-related physical trauma was commonplace. One example from a prison in Michigan City, Indiana reported that over one year, there were 245 accidental injuries or deaths among a population of 378 inmates, meaning that about one-third of workers were critically and permanently disabled, or killed by their work environment.7 If incarcerated laborers did not face potential physical damage due to their work environment, it was provided courtesy of those who oversaw inmates’ work. Inmate workers could be subjected to beatings or outright torture for a number of reasons: breaking rules, failing to produce the required number of products in the allotted time, damaging equipment—accidentally or purposely—or for no reason whatsoever. Two especially brutal forms of prison torture were “thumb tricing,” where a prisoner would be lifted off their toes by their thumbs, which were tied to a fishing line attached to a pulley connected to the ceiling, and a form of water torture similar to that of water boarding, which replicated the sensation and subsequent nervous shock of drowning. Throughout the nineteenth century, prison factories in the North achieved high rates of labor productivity through the mental and physical torture of inmates, private enterprises sometimes making profits of up to twice the initial costs of convict labor.8 It seems highly unlikely that a more inhumane system of prison labor could have existed in the United States, however, the convict leasing system used in the post-Civil War American South proved to be an even worse incarnation of prison labor, where former African-American slaves could be arbitrarily arrested, convicted, and forced into one of the deadliest forms of prison labor to ever exist.

Convict leasing in the post-Civil War South was a consequence of the Thirteenth Amendment’s legitimization of involuntary servitude as a form of legal punishment for criminals.9 Because the southern economy was almost entirely dependent upon the free labor gained from black slaves, once slavery was outlawed in the United States, Southern states saw their economic foundation shaken and in need of assistance. The result was the convict leasing system, a form of prison labor which specifically exploited black male prisoners and subjected them to cruel and inhumane labor until death. Prior to and after slavery had ended, an African-American in the South could be arrested arbitrarily, and if arrested, had little to no chances of appealing their arrest in court due to the southern culture of intense racism towards black people, whose plight was justified out of a perceived inferiority. Blacks could be arrested for any reason whatsoever—after slavery was made illegal throughout the country, former slaves could be arrested on the grounds of simply existing. Furthermore, because the definition of what entailed “vagrancy” was expanded within the Thirteenth Amendment, former slaves who had just escaped plantations and were looking for work in cities or hiding in the countryside could be arrested on the grounds of being “vagrants”—essentially sent to prison based on the premise of not having a home, being that their former home was their slave master’s. Private companies who caught wind of this new, cheap system of prison labor would search through the southern countryside for the purpose of “acquiring” laborers—usually black—for work. In reality, acquiring laborers entailed paying corrupt government, prison, and police officials to arrest, convict, imprison, and ship black convicts to private companies. So, under this new system of prison labor, thousands of African-Americans who were likely to not have committed any crimes were thrown into the penal system and made to work for free while awaiting their eventual death, often facing punishment equal to if not worse than those used in the northern industrial system.10

Inmate laborers working within the convict leasing system were not held in actual prison infrastructures, but rather, contained in and chained to rolling cages which roamed across the South building railroads and working in coal mines, sawmills, phosphate beds, and brickyards. Under the convict leasing system, a former slave who had finally been able to escape the brutality of southern plantation slavery could also find themselves back on a cotton or sugar plantation if arrested, convicted, and sent to prison. Conditions in this system were even worse than that of prison factories in the North. Convicts often worked for fifteen to seventeen hours a day, were malnourished due to being underfed, and also worked within disease ridden environments.11 As under slavery, a convict could be beaten purely for the pleasure of it, and torture was a typical mode of discipline for “unruly” workers. Labor managers often carried with them the same tools of discipline being used on slave plantations, equipping themselves with whips, shotguns, bloodhounds, and sweat boxes. Workers were literally worked to death within the convict leasing system—in Mississippi, no convict lived long enough to serve a sentence of at least ten years, while in Texas the average lifespan of a convict was seven years. Meanwhile, companies involved in convict leasing saw enormous economic gains from the system, where widespread convict death typically equated to extremely high rates of productivity.12 Unable to fight or protest their conditions due to the constant threat of physical violence, convicts in the south were forced to work under this system until it died out in the early twentieth century.

Contemporary Prison Labor (Late Twentieth to Twenty-First Century)

Contemporary prison labor, while still arguably inhumane on some levels (prisoner abuse notwithstanding), is much tamer in comparison to its nineteenth and early twentieth century incarnations. Furthermore, in 2014, it was reported that about 31 percent of state and federal correctional facilities employ inmates in a prison industry—since not every inmate at every one of these facilities is employed in a prison-work job, the actual number of inmates who engage in prison labor is actually quite low in comparison to the total number of inmates in the American penal system.13 Modern American prison labor is also not a punishment in and of itself, prisoners having the option to work in prison though they are not required to do it. Actually, for some inmates across the United States, prison labor can be more a privilege than a punishment, as some in-prison jobs can offer vocational experience, work locations outside of prison walls, and a chance to reconcile their past mistakes. Besides the job-specific benefits that some present-day forms of prison labor offer, many prisoners, correctional officials, and prison administrators believe prison labor can alleviate feelings of idleness and boredom, while also instilling a sense of schedule and work ethic in inmates who failed to achieve this outside of prison.14 Commodity production in prison still exists, though this aspect of prison labor is a shell of its former incarnation, as “prison household production” and various types of community service work have become more available to inmates. Commodity production labor is, however, a highly sought after and regarded prison job, often having higher wages and more benefits in terms of applicable work experience post-release.15 Some commodity production labor, like agricultural work in Colorado where inmates replaced migrant workers, are not so glamorous, this job only paying about $0.60 a day for arduous work that entails harvesting a number of crops, including corn, peppers, and melons.16 Prison household production, the field of prison labor most inmates end up working in, refers to non-market work like laundry, cleaning, dining hall staffing, and general maintenance—jobs which serve to benefit the greater in-prison community, but pay less than jobs in commodity production. “Community service” jobs can occupy a wide-range of possibilities and are found both within and outside of the prison walls.

Contemporary Examples of Prison Labor

California’s Prison Fire Camps

California’s prison fire camps have become a highly scrutinized form of prison labor in recent memory, often being sensationalized in mainstream media for its perceived exploitation of inmates. Having prisoners handle California’s wildfire problem seems like a very precarious and inhumane way of subjecting inmates to labor, however, only a very small percentage of California’s in-custody population actually works in these fire camps—about 4,100 inmates across forty-two fire camps—and they are typically tasked with doing vocational grade labor, not fighting fires.17 There are a number of eligibility requirements an inmate must satisfy before being considered for the job, including not having committed a violent crime, having five years or less left in a sentence, and deemed “low security” by a correctional officer. If accepted into the program, inmates are usually tasked with doing manual grade labor which can include golf course maintenance, roadside trash pickup, public park landscaping, and installing specialized nets at a fish hatchery. This work usually earns inmates $1.45 a day (about $43.50 over thirty days), while actual firefighting earns them a $1 an hour over twelve- or twenty-four-hour shifts, though this can be subject to change depending on the size of the fire.18 Most of the firefighting inmates do end up doing is not “firefighting” in a traditional sense. Rather than use water hoses, inmates work on “hand crews” engage in “cutting fire line,” which entails clearing areas of land covered with trees to prevent fires from spreading further.19 Since inmates are not working within the confines of prison walls, and there is no commodity being produced, fire camp labor falls along the lines of inmate service work, as they are providing a service in the form of preventing fires.

Surprisingly, a number of inmates actually reported satisfaction with their jobs at the fire camps. “Mike” commented on how getting out of the camp made him feel like he’s free, as if he’s no longer in prison though he’s still technically incarcerated. “Potter” believed the fire camps could help instill a sense of schedule in inmates who were never used to a steady regimen, and this emphasis on schedule can keep inmates from ending back up in prison after their release.20 “Stephen” thought working as a firefighter could be beneficial to righting the wrongs of his past, believing his acts of public service like saving people and animals from fires might absolve him of some of his past mistakes. Some inmates, however, report dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the fire camps.21 “Andre” felt as though the correctional officers were dismissive of, and at times, levied somewhat abusive behavior towards the inmates. Andre alluded to mental (and possible physical) abuse from correctional officers, specifically noting how this abuse is meant to trigger a reaction from inmates which could lead to them being kicked out of the program.22 Another prisoner, “Tom,” comments on how he feels like the stigma of being a prisoner keeps people from seeing them as anything other than a potential murderer or rapist. While some people have thanked him and his teammates for their help in quelling wildfires, Tom believes most bystanders only see their “prisoner” labels and not the good they are doing for society. In a similar example, female inmates at an all-women fire camps reported prejudice from non-incarcerated firefighters, who refused to share their coffee with the prisoner firefighters because of their status as prisoners. This hostile behavior towards fire camp inmates has actually been reported to be a fairly common occurrence.23 Experiences within the fire camps have been mixed at best, inmates reporting both positive and negative aspects of the job. It must be noted, however, that all of the positive experiences that were attributed to fire camp labor had to do with the actual work being done at the camp, while the negative experiences were all along the lines of interpersonal communication and having to reconcile with the stigma of being inmates.

Pennsylvania Correctional Industries

Pennsylvania Correctional Industries (PCI) is a unique program within the Bureau of the PA Department of Corrections and operates as an independent business whose main goal is to rehabilitate inmates through employment, vocational training, and work experience. This program emphasizes ensuring a successful transition from prison to free society through employment and offers a variety of different jobs catered to increasing work experience in a specialized (and non-specialized) field. There are thirty-five PCI factories across nineteen prisons, which employ about 1,487 inmates as of May 2013.24 Like the California prison fire camps, PCI does have a few eligibility requirements for inmates looking to apply for a position, including a clean disciplinary record, at least an eighth-grade reading level, and a sentence with two to six years remaining. When accepted into the program, inmates have the option of working within either non-specialized or specialized fields of work. The specialized forms of prison labor range from optical services—a women-only job which requires a six-month intensive course that enables one to take the American Board of Opticianry certification test—to woodworking and furniture upholstery, while non-specialized labor mostly refers to working in the garment factory. Because most of the commodities produced through PCI are used in prisons and general corrections infrastructures, PCI falls along the lines of both prison household and commodity production, inmates producing commodities which directly benefit inmates, but also state officials and correctional officers.[26. Richmond, “Why Work While Incarcerated?” 238.]

Inmates can receive hourly wages between $0.19 to $0.42, depending on what field they work in and if the work is specialized or non-specialized. Regardless of which field an inmate decides to work in, the hourly wages are far less than the wages offered for firefighting, possibly because these jobs pose less of a physical threat to inmates. However, because PCI’s mission is to promote work experience and inmate rehabilitation, the program provides bonuses where an inmate can earn $0.70 an hour in addition to the hourly wage they were already making, which, when added to the original wages, could result in an inmate making anywhere from $0.89 to $1.12 an hour, or a staggering $21 more per week than the average prison job.25 Since less than half the inmates working at the prison fire camps work in PCI, and the men and women working for PCI have stricter rules regarding eligibility requirements, inmates needing to have no more than six years left on their sentence and an 8th grade reading level, it makes sense why wages could end up being higher, albeit marginally, than those offered at the camps.26 This could also be due to the fact that the labor offered through PCI can be more beneficial to providing the necessary skills for finding sufficient means of work outside of prison, though the stigma of being an ex-offender will always be a barrier that infringes upon a formerly incarcerated person’s ability to secure work. Still, inmates, especially women, feel as though PCI can be beneficial to their mental well-being—their work instilling feelings of societal contribution and a metaphorical “freedom” from prison.

In a study of 70 inmates working in PCI—38 women and 32 men—the perceptions of PCI were overwhelmingly positive, the dominant sentiments surrounding labor as a beneficial aspect of prison including improvement of self-perception, incentive to avoid conflict, enhancement of interpersonal skills, and job training/education. Inmates also held the PCI staff in high regard, somewhat surprising considering the comments regarding correctional officers at the fire camps. Staff members were reported as being highly knowledgeable about the field they were overseeing and genuinely supportive of inmates, which transitively motivates inmates to work even harder. Inmates saw their staff as facilitating supportive environments where they (the staff) can “show you what you are doing is wrong . . . [but] don’t give up on you,” valuing their opinion in the process and giving inmates the feelings of pride and accomplishment conducive to a healthier mental state. Most responses from inmates about PCI were positive, if not completely supportive of their employment, though opinions on prison labor varied slightly between men and women.27 Male inmate’s perceptions of prison industries labor were related to societal ideals of what it means to be a “man,” such as being a provider for one’s family or being financially independent. In the context of prison, men felt as though prison labor allowed inmates to be self-sufficient, their jobs granting them the ability to spend their money buying personal items from the commissary instead of having to ask a family member, send money home to their families, or simply save for their future release.28 Women, on the other hand, had less of a fixation with the financial aspect of prison labor, instead feeling that their work could grant them opportunities to avoid recidivism by putting themselves on a path that can grant them better employment opportunities post-prison while also promoting self-sufficiency. Since working in optical services is only available to female inmates, and this form of labor is the one which promotes the most opportunities for steady employment post-prison, women took much pride in their work and saw it as a responsibility that held great meaning for them. Comparatively, women working in non-specialized work like garment production did not report their job as having the same meaning to them as women in optical services did.29 In comparison to California’s prison fire camp labor, PCI seemed much more conducive to inmate satisfaction and mental stability, inmates having an appreciation for their work and the staff who oversees their work. The only potentially negative aspect of PCI in contrast to the fire camps is the fact that PCI work happens within the prison walls, while the camps afford inmates a rare opportunity to live amongst the outside world.

Special Needs Program for Inmate-Patients with Dementia (CA)

The Special Needs Program for Inmate-Patients with Dementia or SNIPD is an interesting form of prison labor, almost every aspect of the program standing in stark contrast to the fire camps and PCI. Also referred to as the “Gold Coats” program because an inmate caregiver’s gold-colored coat identifies their line of work, the California-based SNIPD recruited just six inmates to look after 170 elderly inmates, twenty-six of whom have moderate to severe dementia. This work is mostly related to “community service” prison labor, though the fact that inmates are caring for fellow prisoners and ensuring their wellbeing also makes the job akin to “prison household” work. The eligibility standards for work opportunities in SNIPD are noticeably stricter and more rigid than the other aforementioned forms of labor, requiring inmates to have a life or generally long sentence, at least a decade without disciplinary violations, no history of mental, emotional, or cognitive issues and impairments, and a clear history of commitment to in-prison community service. Inmates looking to get involved in SNIPD must also complete a twelve-month training course given by the Alzheimer’s Association, the longest of any training course mentioned thus far. The job pays $0.25 an hour which after a month totals to equal around $35, slightly less than the monthly income of a fire camp if there are no fires to fight and assuming inmates work every day over the course of about thirty days.30 Inmates in this program actually make far less than California inmates who are actively fighting fires and Pennsylvania inmates consistently receiving hourly wages plus bonuses. Assuming an inmate at a prison fire camp worked twelve hour shifts for $1 an hour every day for thirty days, they’d be making $12 a day which would total to well over $300 a month (about $360, not bad for an inmate), while an inmate working within the PCI, assuming they are working more normalized hourly shifts—a “nine to five” for instance—and gaining a bonus for every shift they work, could make up to $250 a month.

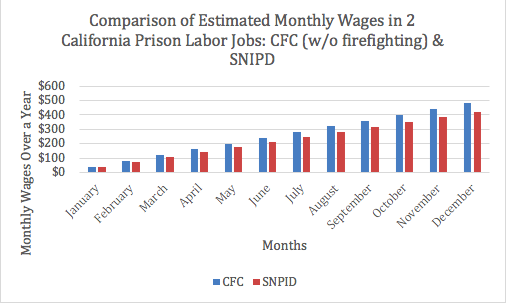

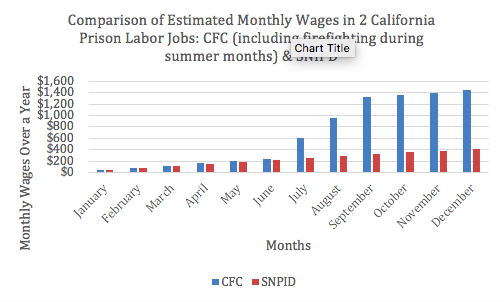

The two graphs below provide a comparison of between wages earned in two California prison labor programs: the prison fire camps or CPC and the Special Needs Program for Inmate-Patients with Dementia or SNIPD. For the purposes of highlighting the stark differences in wages an inmate worker can earn based off the type of job they have, the graphs will compare CPC wages with and without the bonuses earned from wildfire fighting, to the steady wages earned through SNIPD. Because wildfires in California typically occur during the summer months, the wage increases in CPC will affect the months of July, August, and September. To account for differences in days for certain months, for the purposes of providing consistent data in these graphs, every “month” will entail thirty days of work, and work will be assumed to be occurring on a daily basis, including weekends.

This seemingly meager amount of monthly income seems unequal to the work the SNIPD requires of its inmates, since these workers are tasked with the daily care of potentially mentally disabled elderly persons. During the daily life of an inmate working in SNIPD, they can expect to be tasked with sanitary duties like the showering and shaving, in addition to applying deodorant and changing adult diapers. They also assist elderly inmates with everyday tasks such as eating, writing service requests, and bringing them to group meetings and appointments with their nurses. In addition to the daily assistance gold coats must give to elderly inmates for everyday tasks, they may also be tasked with mediating interpersonal interactions between “inmate-patients” and other potentially predatory inmates, or interactions between inmate-patients and correctional officers unaware of their mental instability and prone to using disciplinary action for what they perceive to be acts of unruliness or noncompliance. Two inmates in specific added that it is actually commonplace that they have to protect inmate-patients with dementia and Alzheimer’s from predatory inmates, giving work in SNIPD a precarious, if not dangerous edge.31 Interestingly enough, this job actually pays more in comparison to other jobs offered in prison, perhaps because of its high selectivity, emphasis on stable mental health, and tasks which include constant hands-on care and protection of vulnerable inmates. Still, if SNIPD pays higher than most other prison labor jobs offered at this specific prison, then work at PCI and the fire camps work may actually occupy a very small percentage of high paying jobs in the wider scope of prison labor. Financial incentives aside, the few inmates working in SNIPD did report positive feelings about the work they do as inmate caregivers.

Diana Taylor’s 2016 study of SNIPD included interviews of three men with varying ages and life sentences: David Barnhill, forty-four years old and having served twenty years of a twenty-five year to life sentence, Phil Burdick, sixty-three years old and having served thirty-seven years of a seven year to life sentence, and Secel Montgomery, forty-nine years old and having served twenty-nine years of a twenty-six year to life sentence. These men have all received rather lengthy sentences, for which they have spent many years serving time in prison already—Burdick and Montgomery having been in prison for over half their lives. Despite their life sentences, Barnhill and Montgomery were relatively new to the program, having worked in SNIPD for five years, while Burdick has spent eighteen years, or about half his sentence, working as a gold coat. While the study does not reveal what their crimes were, one can assume their life sentences might have been the consequence of some rather violent or highly illegal activity. It is also possible, however, that these lengthy sentences could be drug crime-related, and potentially the result of corrupt sentencing practices—because the study does not provide any specific information about the inmate caregivers outside of their sentences it is hard to make an educated guess. All three men indicate, to some extent, that the reason they joined SNIPD was to make amends for past crimes and unlearn some of the negative mentalities that landed them in prison. They all reported massive shifts in mental and emotional maturity, believing that SNIPD has taught them to practice empathy, sensitivity, and compassion rather than self-centeredness and selfishness. Phil Burdick feels that his work in SNIPD is similar to that of community service, where he can show remorse “for my past criminality and to my victims and their families . . . and my own families as well,” while Montgomery also shared similar sentiments about SNIPD enabling him to give “back to society for the crime I committed.”32 Though they reported SNIPD as having the necessary tools and atmosphere to facilitate inmate mental rehabilitation, there was some uncertainty regarding whether or not this program should become more available to inmates. Harkening back to one of the prisoner’s daily tasks, which can include fending off predatory inmates, Phil Burdick believes SNIPD is not for everyone who is an inmate, as the prison atmosphere has caused many inmates to harbor predatory mindsets that can lead to possibly dangerous interactions with inmate-patients. While all three men report positive changes on an individual level, Burdick strongly believes that not every inmate will discover, or even desire to see, the same changes they experienced as inmate caregivers.33

Prison Labor: Exploitation?

Though the jobs offered at the California fire camps, through PCI, and SNIPD three jobs are relatively rare and specialized within the wider scope of prison labor, it is clear that the prison labor of the twenty-first century is far more humane and conducive to inmate satisfaction, self-sufficiency, and rehabilitation than its historical precedents. Nonetheless, it must be repeated that the jobs in these various studies are not reflective of the wider market of prison labor work. In fact, it is much more likely that an inmate will end up working in prison household production, which is available to all penitentiaries that offer prison labor work since there will always be a need for people to clean laundry, cook meals, clean facilities, and oversee general prison maintenance. Despite drastic increases in the humane treatment of inmate laborers, there were still sentiments of inmate exploitation, even among the highest paying jobs. At the prison fire camps, one inmate named “T.C.” remarked that his work as a firefighter is reminiscent of legalized slavery, while a camp officer named “Rick” supported T.C.’s sentiments by adding in that he believes that the inmates who help put out the fires work the hardest and do the bulk of the “nitty gritty” work, yet are under-appreciated in comparison to firefighters which he perceives to not do nearly as much work as the inmates.34 This adds an interesting angle to the inmate complaints about a lack of respect from non-prisoner firefighter from earlier, an officer actually substantiating inmate complaints through his personal account. Other complaints regarding inmate exploitation at the fire camps reference low wages. Though camp inmates can make a substantial amount of money during wildfire season, their off-season grade work—which pays a fixed rate of $1.45 a day—would equate to under $0.20 an hour, assuming inmates work around seven to eight hours a day when not fighting fires. In this case, the more hours these inmates work at the fire camps, the less their hourly rate, so if an inmate is working, say, a ten-hour day, their hourly wage would only be about $0.14 an hour because their daily pay is $1.45. Thus, wages at the prison fire camps are actually set to be equal to, if not lower than, the lowest wages being offered in PCI. Perhaps the low wages are justified by the fact that fire camp work allows inmates to work in nature among forests, clean air, and wildlife, as opposed to the barren metal and concrete infrastructure of prison. This aspect of the fire camps could be perceived as an added privilege, though when it comes time to actually fight fires, inmates do not seek their work as being all that glamorous.35

Prison Labor and Recidivism

Despite low wages, work experience that may or may not be applicable post-prison, and the “criminal” stigma ex-offenders face in the job market after their release, there are claims that prison labor can limit recidivism. Many of the inmates interviewed across the three studies report their jobs as having beneficial effects on their work experience, work ethic, and overall sense of confidence in the workplace. These benefits, however, are offset by the fact that not every one of these jobs will be useful in the job market post-release, and that these jobs can just as easily go to someone who does not have a criminal record. A 1992 study on the effects of prison labor on recidivism found a positive correlation between prison labor and lowering recidivism among seven thousand inmates who were released from incarceration over the course of several years. What is interesting about this study is how recidivism was defined, being distinguished as “survival time,” or the amount of time an ex-offender lasts in free society before committing another crime. The study found that there could be a 20 percent increase in survival time for those who worked in prison labor while serving their sentence. In this context, this could mean that an inmate returning to prison in thirty-six days as opposed to thirty days would be seen as “favorable” results. In reality, this marginal increase in time spent not in prison does not mean an ex-offender will not end up committing another offense, but that they may end up spending longer periods of time not in prison before eventually returning.36

Another report, conducted in 1988, studied prisoner recidivism in seven max-security New York penitentiaries among 896 offenders, 399 having participated in prison industries and 497 being nonparticipants. Instead of using “survival time” as a means of defining recidivism, this study uses the traditional definition of recidivism alongside a “hazard rate,” which entails the probability of an occurrence or event that will happen to an individual that will end in their arrest. What the study found was that prison labor participation was not statistically significant in prisoner recidivism. Furthermore, the study actually suggested that participation in prison industries could slightly increase one’s hazard rate, leading to higher chances of re-arrest.37 One take away from this study is that prison labor, occurring relatively late in an inmate’s life, after they have already grown accustomed to certain social and psychological factors that led them to incarceration, while happening in a context where they are working in a setting not necessarily conducive to unlearning these behaviors, means that just because they spent a few months or years in a work program will not necessarily mean they will return to society as law-abiding, stand-up citizens.38 Furthermore, the possibility of prison labor having a positive effect on a former inmate does not eliminate the factors in their communities that may lead them to commit crime in the first place. How can someone who was just sent home from prison be expected to find work in a community with few means of viable work opportunities, or even apply what they’ve learned in general if there are no outlets available for them to do so?

Though this study was conducted in the late eighties, the total in-custody prison population has drastically increased since then, and because only about 31% of United States prisons offer work opportunities to begin with, it seems highly unlikely that prison labor could have any substantial effect on prison recidivism today.

Concluding Thoughts

Prison labor in the United States has seen an intriguing trajectory over the past few centuries. What began as a disciplinary aspect of prison akin to legalized slavery, has now become a somewhat useful tool for promoting a more stable, more productive prison environment. Prison labor conditions of the nineteenth century were so deplorable that one could actually be killed by their work, their overseers, or the physical environment itself. Today, prison labor seems to promote more of a rehabilitative, rather than disciplinary, mission, though the likelihood for rehabilitation is relative to the job an inmate is able to work. However, the selectivity inherent in prison labor programs, as well as the fact that not all prisons offer work opportunities, means that only a very small percentage of the total prison population is employed, and an even smaller percentage of prisoners will find success and self-sufficiency post-release. The vast majority of inmates, on the other hand, will not attain even a modicum of the benefits—in and outside of prison—that those in the labor system receive. It is hard to truly say whether or not prison labor promotes independence or further instills dependence on a system which suggests a false sense of independence for prisoners. Even if an inmate working in optical services through PCI can pass the course, get their opticianry certification, and flourish in their positions as in-prison opticians, the outside world may prove to be much harsher on those perceived to be former criminals, and these aforementioned skills may prove to be insignificant in the face of having to “check the box” of being an ex-con or having to compete with people who have no criminal record.

- Genevieve Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor: Social Discipline and the State in Historical Perspective, Journal of Labor and Society 15, no. 3 (2012): 332.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,”331.

- Loic Wacquant, Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009) 62.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,” 330.

- Asata Bair, Prison Labor in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2008) 135.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,” 333.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,” 334.

- “Rethinking Prison Labor,” Lebaron 2012, 335.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,” 337.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor, 340.

- Lebaron, “Rethinking Prison Labor,” 338.

- Lebaron, Rethinking Prison Labor,” 339.

- Kerry Richmond, “Why Work While Incarcerated? Inmate Perceptions on Prison Industries Employment,” Journal of Offender Rehabilitation 53 (2014), 244.

- Bair, Prison Labor in the United States, 5.

- Bair Prison Labor in the United States, 5.

- Dan Frosch,“Inmates Will Replace Migrants in Colorado Fields,” March 4, 2007, The New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/04/us/04prisoners.html.

- Goodman, Philip Goodman, “Hero and Inmate: Work, Prisons, and Punishment in California’s Fire Camps,” Journal of Labor and Society 15 (2012): 356.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate,” 357.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate.”

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate,” 359.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate,” 364.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate,” 367.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate, 366.

- Richmond, “Why Work While Incarcerated?” 237.

- Richmond, “Why Work While incarcerated?” 237; 244.

- Richmond, “Why Work While Incarcerated?, 237.

- Richmond, “Why Work While Incarcerated?” 239.

- Richmond 2014, 243.

- Richmond, “Why Work While Incarcerated?” 244.

- Dianna Taylor, “Between Discipline And Caregiving: Changing Prison Population Demographics and Possibilities for Self-Transformation,” in Active Intolerance: Michel Foucault, The Prisons Information Group, and The Future of Abolition, edited by Zurn, Perry and Andrew Dilts, (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.), 113.

- Taylor, “Between Discipline and Caregiving,” 114.

- Phil Burdrick and Secel Motgomery quoted in Taylor, “Between Discipline and Caregiving.”

- Taylor, “Between Discipline and Caregiving,” 114.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate,” 364.

- Goodman, “Hero and Inmate,” 2012

- Bair, Prison Labor in the United States, 133.

- Kathleen E. Maguire, Timothy J. Flanagan, and Terence P. Thornberry, “Prison Labor and Recidivism,” Journal of Qualitative Criminology 4 (1988): 15.

- Maguire, Flanagan, & Thornberry 1988, 16.