“We are hardwired to see patterns, to create explanations, to find meaning, and we do this through constructing narrative.”

The Storytelling Animal

In the year 1944, the psychologists Fritz Heider and Marianne Simmel conducted an experiment in which subjects watched a short animated film and then described what happened in it.

Try it out yourself.

How do you make sense of this video? If you’re like most viewers, you didn’t just see shapes moving around a blank background: You saw a story. Heider and Simmel found that the vast majority of their test subjects did the same—they saw characters (with emotions and agendas), conflict, plot, and resolution. But really “saw” isn’t the right word to describe this phenomena. You, and Heider and Simmel’s test subjects, didn’t “see” a story that was already made, rather, you created one on your own. You constructed your own meaning from geometric shapes bouncing around on a screen.

In a creative writing class I took fall 2017, we watched this Heider and Simmel video and at its conclusion shared the descriptions we had written of what happened. Each of our descriptions was unmistakably a narrative. We personified the inanimate figures using words like “escaped,” “slammed,” “danced,” or “kissed” to describe their actions. We depicted them with tempers, or as cowardly, or as viciously conspiring. And, what’s more, we were entirely unconscious of the fact (until the professor pointed it out) that our story wasn’t intended—that we were creating it on our own.

We had translated the arbitrary movements of geometric figures into story perhaps because doing so was the easiest way for our brains to explain what we had seen. For us, our stories were more accurate, ironically, than “the triangle moved in a circular motion,” etc. because we think in story. We are hardwired to see patterns, to create explanations, to find meaning, and we do this through constructing narrative.

As Jonathan Gottschall put it in his 2014 TEDx Talk, “Without story to organize your experience on earth, you would experience your life as a blooming, buzzing confusion.”

And we don’t all create the same story. In fact, it’s almost certain that Heider and Simmel’s test subjects, the comedians who participated in this 2014 version of the Heider-Simmel test, and you, the viewer, all saw vastly different narratives. Some of you may have sympathized with the big triangle, some with the circle, some may have seen it as a home invasion, or a love story, or one of vengeance. That’s the beauty of the human mind, and our instinct to create story—it’s always different. Years from now, if you come across this same Heider and Simmel video, maybe you’ll see the antithesis of your current tale.

This principle of storytelling (more accurately, story-creating) does not only apply to bizarre YouTube videos featuring shapes. We are all perpetual storytellers in and of our own lives—in fact, we often see our lives as a “journey.” When we tell our friends anecdotes from the past, when we gossip or tell jokes, we are striving to find meaning and order in our lives through storytelling.

I decided to take this head-on—to consciously become the storyteller of my own past.

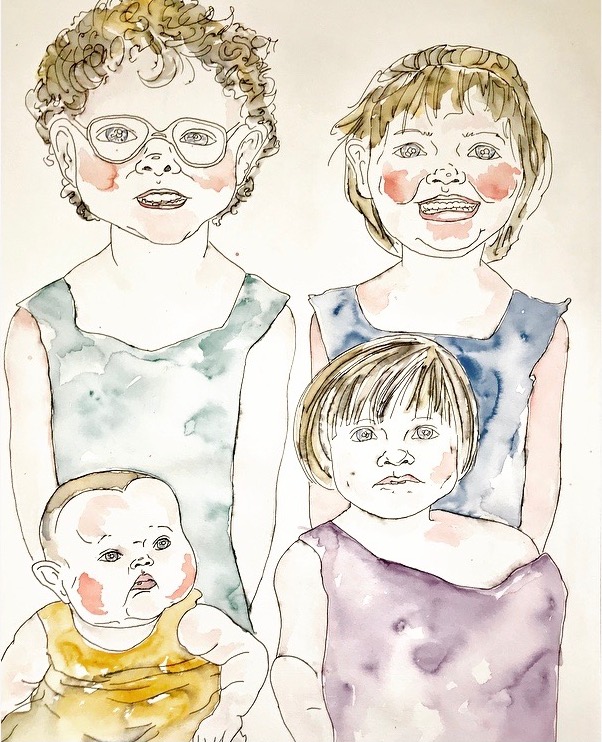

I recently found dozens of home videos of my three sisters and me, shot from our births up until 2005. As I watched them, my brain began to fill in the gaps, to make sense of what I saw. I decided to cut and paste clips together into a short video, fully aware that the narrative that was emerging for me, from snapshots of a life long gone, would be constructed into a uniquely separate story by each viewer.

Have a look.

How did you make sense of this video?

Perhaps, for you, it sparked memories of your own childhood, your own family. Maybe, for many of you, the story is one of discovery and identity, or childhood bliss and naivety, or home and family. Or, you could have taken the video more literally and seen it as the chronicle of a child’s perfect day, filled with fun activities: swimming, sandcastle-making, playing at the park, visiting the zoo, painting and opening presents.

And that’s what is so incredible about storytelling—stories are malleable, they mold to each person they greet. So the story that you create when you watch this video (whether it be powerful or boring) is entirely different from the story that I see. And, of course, this is because for me many of the gaps that you fill in are already shaded: They’re my own life history.

When I watch the video, the narrative playing in my mind does not center around where the camera is pointing, the four soon-to-be-orphaned little girls on-screen, but rather who is pointing it. For me, this video depicts a silent conversation between the past and the present, connecting present-day me to the videographers.

The video does not only revive my parents’ physical voices, allowing for a literal echoing of the conversation through vocalization of words long faded, but it also revives their personalities and their personhoods. When we lose someone, we often idealize them in their absence, making them untouchable, inaccessible and impersonal.

By hearing their voices and personalities in these mundane shots of everyday life, I am able to conceptualize the fact that they were people, who brushed their teeth, got bored, and joked just like we all do. So, for me, the conversation is resumed in that I am able to see them for what they really were—people—rather than viewing them through the mist of death and time.

Finally, and in a similar vein, the conversation is picked back up for me in that I am able to see their perceptions of me as a child. Because when watching (and making) this video I am forced to take a third person, audience-like position, I am able to see more objectively and richly the way that they saw me, and I am able to transfer this onto myself now, and wonder and speculate about what they would think of me today.

Our brains use story to sort out the chaos of existence, to shape and mold our reality. Perhaps we search to find the stories we need to hear, the ones that help us to heal from or disentangle the confusion of life. For me, these disjointed clips continue a conversation that was cut short, but for you, through the power of your own narrative carpentry, these clips are transformed into an entirely different story, molded, embellished, and made anew by your thoughts, feelings, and memories.